What Makes a Relationship Intimate?

So far, we’ve been a bit casual in our use of the phrase “intimate relationship.” Because everyone has a pretty good understanding of what couples are all about, a concrete definition might not seem necessary. But in the same way that any couple eventually needs to have a “define the relationship” conversation, we also need to provide clarification, because there’s plenty of room for ambiguity. Is a hookup an intimate relationship? Should we think of a “bromance” (or “womance”)—a really close same-sex friendship that is nonsexual—as an intimate relationship? What if two people are engaged to be married but agree to postpone all sexual contact until after the wedding? And how about a couple who have been together for decades but stopped having sex when their last child left home? Intimate relationship, or not? Let’s use an example to sort this all out.

“Like other great forces in nature—such as gravity, electricity, and the four winds—a relationship itself is invisible; its existence can be discerned only by observing its effects.”

—ELLEN BERSCHEID, SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGIST (1999, p. 261)

Somewhere, as you read this today, two people—let’s call them Emily and Robin—are meeting for the first time. Perhaps they will share an umbrella in the rain, or smile at the fact that they’re both wearing Ezra Furman T-shirts, or maybe they’ll commiserate while waiting for a professor who has failed to show up for office hours. They might engage in small talk as the rain dies down, converse about their guilty binge-watching pleasures, or arrange to study together later that day; ultimately, they might exchange phone numbers so they can stay in touch. No longer strangers, Emily and Robin text each other, find out whether each is already involved with someone else, spend more and more time together, and laugh at their good fortune of having worn those T-shirts and met on that fateful rainy day. As time passes Emily and Robin start to think of themselves as a couple, are identified as a couple by their friends, and agree to date only each other; they might have sex, disclose self-doubts, and wonder, however tentatively, about a future together.

Most of us would think of this couple as now being in an intimate relationship. But why do we think that? What are Emily and Robin doing that leads us to view their relationship as intimate? And what happened over the course of these several weeks that changes how we think about them and how they think of themselves? Asking these questions allows us to introduce four criteria that define an intimate relationship.

Interdependence Is the Cornerstone of All Relationships

First, and most basically, you may have noticed that Emily and Robin affected each other right from the start, and then more and more as time passed. Referred to as interdependence, the mutual influence that two people have over each other is the defining feature of any social relationship, intimate or otherwise. Early on, Emily and Robin’s connection was superficial, but eventually it grew stronger and deeper. If Emily sprained her ankle right after they first met, the smiley-face emoji with the thermometer might have worked for Robin. But the same injury weeks later might motivate Robin to bring Emily dinner and notes from English class—demonstrating real caring, and prompting Emily to deliver chicken soup when Robin comes down with the flu.

What is interesting about interdependence is that it exists between two partners in a relationship, as if they were surrounded by an invisible net. And there is something else that’s special: Interdependence is bidirectional, meaning it operates in both directions at once. Emily affects Robin, and Robin affects Emily. Without bidirectional interdependence, there can be no relationship. Contrast this with a unidirectional influence, like the kind that commonly happens when people use Tinder, the dating app: If only you swipe right, only you will get your hopes up about getting to know the cute person in that picture. The effect is unidirectional, and no relationship can happen. But if you and that cute person both swipe right, then lines of communication might open up. Both partners acting in concert determined the next step in their relationship. Bidirectional influence is now possible, allowing opportunities for interdependence to grow even more.

Emily and Robin’s interdependence is interesting for another reason: It extends over time, with later exchanges gaining meaning from earlier ones. We wouldn’t say they had any real connection after that first brief meeting, because there was no prior interaction to build upon. However, we can see how their later musings about their good fortune in finding each other take their significance from that meeting. As ethologist Robert Hinde notes:

“Relationship” in everyday language carries the . . . implication that there is some degree of continuity between the successive interactions. Each interaction is affected by interactions in the past, and may affect interactions in the future. For that reason a “relationship” between two people may continue over long periods when they do not meet or communicate with each other; the accumulated effects of past interactions will ensure that, when they next meet, they do not see each other as strangers. (1979, p. 14)

Can we conclude that Emily and Robin’s bidirectional interdependence is the reason their relationship would be described as intimate? Not entirely. Interdependence is a necessary condition for intimacy—you cannot have intimacy without it—but it is not a sufficient condition for intimacy. After all, many relationships possess bidirectional interdependence but aren’t intimate, at least as we are defining intimacy here. A guard and a prisoner are interdependent but not intimate, as are a shopkeeper and a regular customer, a patient and a nurse, a mother-in-law and a son-in-law, two friends, and so on. In all these cases, the two individuals have enduring and bidirectional influences over each other—yet we would not say they are intimate. What’s missing? What do Emily and Robin have that a patient and a nurse do not?

Only Some Social Relationships Are Personal Relationships

Intimate relationships occur not just between two interdependent people, but between two people who treat each other as unique individuals rather than as interchangeable occupants of particular social roles or positions (Blumstein & Kollock, 1988). The interdependence within the relationships involving the guard and prisoner, the shopkeeper and the regular customer, and the patient and nurse are driven primarily by the contexts and roles in which these people find themselves. Substituting different people into these relationships would not change them much; your relationship with your dentist is probably pretty similar to my relationship with my dentist. These relatively impersonal relationships tend to be formal and task-oriented.

Personal relationships are relatively informal and engage us at a deeper emotional level. Take, for example, the personal relationships involving a grandparent and grandchild, a mother-in-law and son-in-law, or two friends, or our couple Emily and Robin. In these cases, the interdependence is likely to be longer lasting and determined less by social roles and more by the uniqueness of the individuals involved. Swapping out one grandparent and inserting another would change the very character of the relationship, but swapping out one nurse for another should not change the relationship much at all. The unique character of personal versus impersonal relationships is demonstrated by our very different reaction to losing a grandparent than, say, to losing our favorite Starbucks barista—no matter how good the cappuccino.

Only Some Personal Relationships Are Close Relationships

Are all personal relationships intimate ones? Probably not, because the different sorts of personal relationships vary enough that we can still make meaningful distinctions among them. Even in relationships where people treat each other as unique individuals, their degree of closeness varies quite a bit. Most of us would probably agree that a relationship between a mother-in-law and her son-in-law is not as close as a relationship between a grandparent and grandchild, which in turn is not as close as the relationship between Emily and Robin.

But what is closeness? According to Harold Kelley, a social psychologist, “the close relationship is one of strong, frequent, and diverse interdependence that lasts over a considerable period of time” (Kelley et al., 1983a, p. 38). With Emily and Robin, we can see how closeness reflects an unusually high degree of interdependence. Compared to the relationship between a mother-in-law and her daughter’s husband, for example, Emily and Robin will have far more contact with each other because they see each other nearly every day, and the effects they have on each other can be quite strong and wide-ranging. If Emily has a bad day, her mood will affect Robin a lot more than anyone else in her life. If your grandmother has a bad day, that is unfortunate but probably will not require a lot of adjustment from you; though it is a personal relationship, it is just not that close. Therefore, the presence of closeness adds something special to personal relationships, as reflected in the strength, frequency, and diversity of the influences partners have over each other.

Only Some Close Relationships Are Intimate Relationships

Is closeness the final ingredient, the special sauce that makes a personal relationship truly intimate? Consider your own relationships. Do you make a distinction between, say, your closest friendships and a romantic relationship you might have with another person? Most people would say there is a difference here, which means that closeness—the sum total of all those strong, frequent, and diverse influences—is necessary but is not enough by itself to define a relationship as intimate. What’s missing?

We would argue that there is no single ingredient that turns a close relationship into an intimate one. Instead, there seems to be a continuum between our close relationships and our intimate relationships, where a relationship is more intimate the more it includes any of a set of psychological experiences that serve to deepen and expand our connection to another person (Table 1.1). Some of our closest relationships may involve a few of these experiences, but our intimate relationships are likely to involve most of them, leading to a sense of closeness far beyond what we might have with a friend. An intimate relationship therefore includes all the aforementioned elements of closeness (i.e., mutual interdependence and strong, frequent, and diverse influences on each other), but now that interdependence penetrates into the core of the partners’ identities, and as a result intimate partners are more likely to invest themselves heavily and perhaps exclusively in each other’s welfare and well-being.

|

1. Desire: Wanting to be united with the partner, physically and emotionally. The only thing I can compare it to is like a hunger, like being starved and really needing something. Sexually, definitely, but even now being around him just makes me feel good, deep down. I’m not saying it is logical, but it is real. The feeling is not as strong as it used to be, but I certainly recognize that craving when it comes. |

|

2. Idealization: Believing the partner is unique and special. Have we had the greatest relationship of all time? No. But even after all these years, I can see that there is no one quite like Annie. She has an energy about her that I still find attractive, and she has a genuine kindness that is really rare. Together we have created something special, and I would not trade that for anything. |

|

3. Disclosure: Sharing events, emotions, and experiences. Before COVID, we were commuting every day, grabbing a quick meal, even working after dinner. It was fine, but I now see we were in a rut. We both work from home now, and that presents its own challenges, but we make time to take a walk every night, checking in with each other and talking about stuff that really matters. |

|

4. Coordination: Working together to accomplish key projects and tasks. We thought we were busy with two kids, but when Diego arrived it was pure chaos. Graciela and I were both working, and the amount of effort it took to juggle school drop-offs, daycare with her mom, and meal preparation was insane. We were in synch most of the time, but this put our communication skills to the test! |

|

5. Proximity: Taking steps to maintain or restore physical closeness or emotional contact with the partner. I know it sounds strange, but my boyfriend is back home in Japan and so I use one of his T-shirts as a pillowcase. I never want to forget him, or his voice, or what he smells like. I like knowing that I am hugging some small part of him every night when I go to bed. |

|

6. Prioritizing: Giving the relationship more importance than other interests and responsibilities. Look, I’ve got a lot going on, with work, the kids, volunteering at the church, and the dudes I ride bikes with. But in the midst of all this, Alyson is my rock, and she comes first—we come first. We’re not rigid, and we compromise a lot, but still I know I have to invest in this foundation to make our lives work smoothly. |

|

7. Caring: Experiencing and expressing feelings of empathy and compassion for the partner. Our relationship has had its share of ups and downs. When Martin was diagnosed with cancer, though, I stepped up, coordinating with his doctors and the insurance companies. I made sure he knew that I was there 24-7 to care for him. In a strange way that drew us closer together. I know he would do the same for me. |

|

Source: Adapted from Berscheid, 1998; Fehr, 1988; H. Harris, 1995; Hatfield, 1988; Sternberg & Grajek, 1984; Tennov, 1979; and others. |

One advantage of defining intimate relationships as a set of likely features—no single one of which is necessary by itself—is that our definition allows for two individuals to be very intimate, even in the absence of an ongoing sexual relationship. For example, couples who have been together for many years, prioritizing, caring for, and remaining in close proximity, can still be viewed as intimate even if they no longer experience much desire for one other. And, as you will learn in Chapter 5, asexual individuals can be highly intimate without engaging in sexual interactions of any sort.

At the same time, this definition also recognizes that sexual activity and desire alone provide no guarantee that the relationship is intimate. According to our definition, sexual interaction without the element of closeness, and without other distinguishing features of intimacy, falls outside our definition of an intimate relationship. This means that one-night stands and sexual experiences people have when hooking up do not constitute intimate relationships as we define them here. Although two people may be physically intimate, and they might eventually become more intimate in other ways, the fact that key elements of intimacy are missing means they are not in an intimate relationship yet.

Reviewing the list of features in Table 1.1, you will notice that defining an intimate relationship in this way does not imply that two intimate partners are necessarily happy in their relationship. Partners might not idealize each other that much, for example, and they might not engage in much disclosure or caring; however, we would still consider this an intimate relationship if they continue to care for, remain near to, and prioritize each other. But intimacy and happiness do tend to go hand in hand. Einstein’s troubled marriage to Mileva was likely an intimate relationship (at least minimally), but he probably experienced far more intimacy and far more happiness in his marriage to Elsa.

Finally, the seven attributes presented in Table 1.1 hint at why intimate relationships vary so widely in their quality or level of happiness: Both partners are contributing to the relationship and might disagree in how to do so. After all, two people in a relationship might differ in how much they prefer to disclose their emotions to each other, or they might disagree on what it means to demonstrate caring and affection, or they might feel as though they alone are making the necessary sacrifices for the partner and the relationship. Feelings like anger, frustration, sadness, and anxiety arise as partners struggle to make the relationship mutually fulfilling, and of course feelings like joy, happiness, and contentment commonly arise when challenges like these are successfully met.

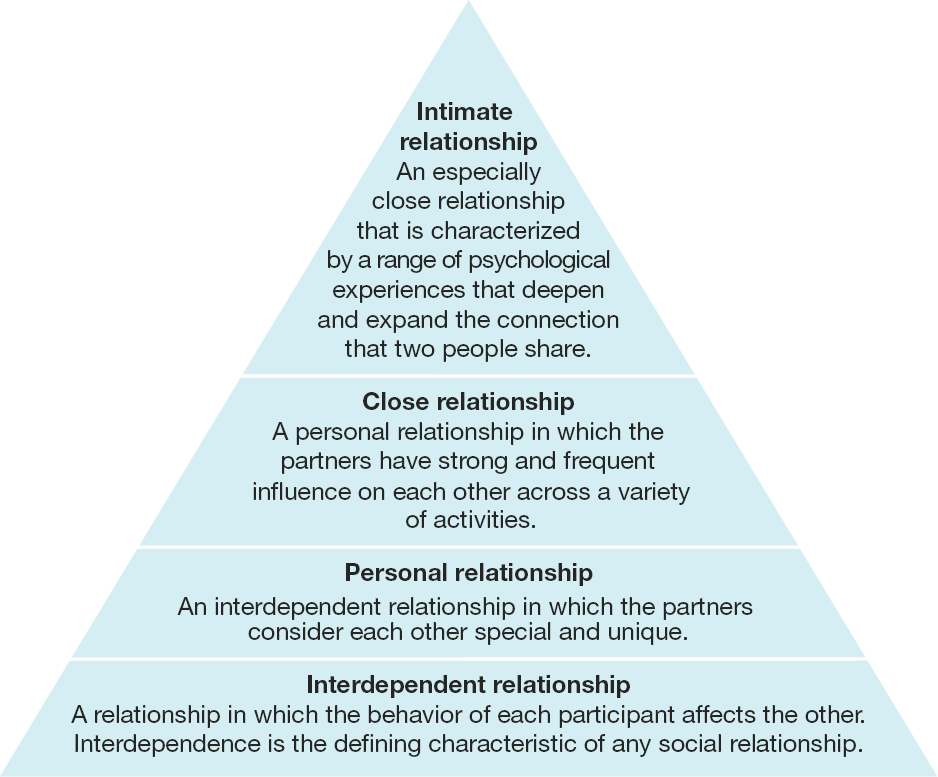

Figure 1.12 captures the essence of the different types of social relationships we have described in this section, allowing us to define an intimate relationship as being characterized by strong, sustained, mutual influence over a broad range of interactions, particularly when those interactions serve to deepen and expand a sense of closeness beyond that in a friendship.

More information

A pyramid outlines different types of relationships. The levels from top to bottom are: Intimate Relationships, Close Relationships, Personal Relationships, and Interdependent Relationships. Intimate relationships are the closest relationship and include some kind of shared sexual passion. The most basic relationship level is Interdependent and is the defining characteristic of any social relationship. The intimate relationship tier reads, an especially close relationship that is characterized by a range of psychological experiences that deepen and expand the connection that two people share. The close relationship tier reads, a personal relationship in which the partners have strong and frequent influence on each other across a variety of activities. The personal relationship tier reads, an interdependent relationship in which the partners consider each other special and unique. The interdependent relationship tier reads, a relationship in which the behavior of each participant affects the other. Interdependence is the defining characteristic of any social relationship.

FIGURE 1.12 Distinguishing different types of social relationships.

MAIN POINTS

- Four criteria distinguish intimate relationships from other types of social relationships.

- An intimate relationship involves bidirectional interdependence, which means that the partners’ behaviors affect each other.

- An intimate relationship is personal, in the sense that the partners treat each other as special and unique, rather than as members of a generic category.

- An intimate relationship is close, where closeness is understood to mean strong, frequent, and diverse forms of mutual influence.

- An intimate relationship is characterized by a range of psychological experiences that deepen and expand the connection that two people share.

Glossary

- interdependence

- The mutual influence two people have over each other; the defining feature of any relationship. As relationships are characterized by bidirectional interdependence, both members have the capacity to affect each other’s thoughts, feelings, choices, and behaviors.

- impersonal relationship

- A relationship that is formal and task-oriented, shaped more by the social roles individuals are filling than by their unique personal qualities. See also personal relationship.

- personal relationship

- An interdependent relationship between two people who consider each other to be special and unique. See also impersonal relationship.

- closeness

- A property of relationships that is reflected in the strength, frequency, and diversity of the influences partners have over each other.

- intimate relationship

- A relationship characterized by strong, sustained, mutual influence across a wide range of interactions, typically including lustful desire and the possibility of sexual involvement.