LEARNING OBJECTIVE

- Assess the importance of the social situation versus individual characteristics, such as personality traits, for determining how we behave.

The modern history of social psychology begins with Kurt Lewin, a Jewish Berliner who fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s and became a professor at the University of Iowa and then MIT. Lewin studied physics and applied a powerful idea of that discipline to an understanding of human social life. He believed that the behavior of people, like the behavior of objects, is always a function of the field of forces surrounding them (Lewin, 1935). To understand how fast a solid object will travel through a medium, for example, we must know such things as the viscosity of the medium, the force of gravity, and the strength of any initial force applied to the object. In the case of people, the forces are psychological as well as physical.

The field of forces in the case of human behavior is the situation, especially the social situation. A person’s physical and psychological traits are also important determinants of behavior, but these attributes always interact with the situation to produce the resulting behavior. The main situational influences on our behavior are the actions, words, and emotions of other people. Friends and adversaries, romantic partners, bosses, and even total strangers can cause us to be kinder or meaner, lazier or more hardworking, bolder or more cautious. People in our environment can produce drastic changes in our beliefs and behavior not only by telling us what to think or do but also by subtly implying through their actions that our acceptability as a friend or group member depends on adopting their views or behaving as they do. To understand why we act as we do, then, we need to think about the power of the situation—a central focus of studies in social psychology.

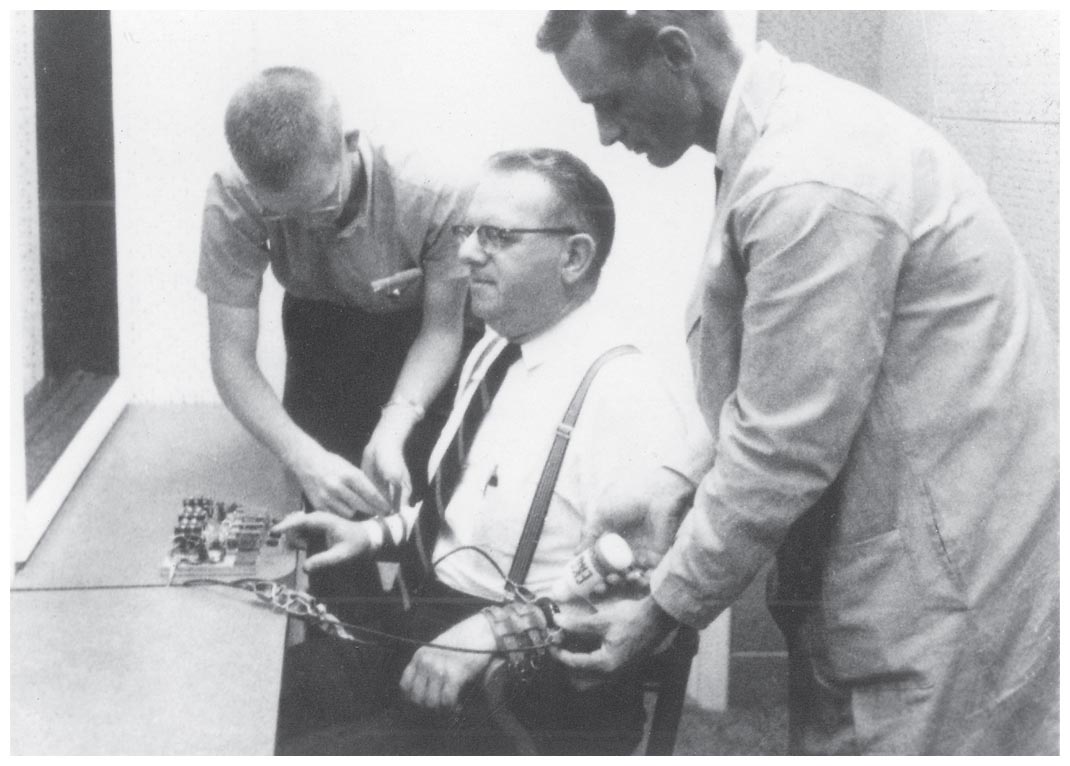

Lewin’s thinking about the power of the situation shaped early studies in social psychology. One of the most striking demonstrations was a classic experiment by psychologist Stanley Milgram (1963, 1974). Milgram advertised in the local newspaper for men willing to participate in a study on learning and memory at Yale University in exchange for a modest amount of money. (In subsequent experiments, women also participated; the results were similar.) When the volunteers—a mix of people from different class backgrounds ranging in age from their 20s to their 50s—arrived at the laboratory, a man in a white lab coat told them they would be participating in a study about the effects of punishment on learning. There would be a “teacher” and a “learner,” and the learner would try to memorize word pairs such as wild/duck. Each volunteer and another man, a pleasant-looking man in his late 40s, drew slips of paper to determine who would play which role. But things were not as they seemed: The pleasant-looking man was actually an accomplice of the experimenter, and the drawing was rigged so that he was always the learner.

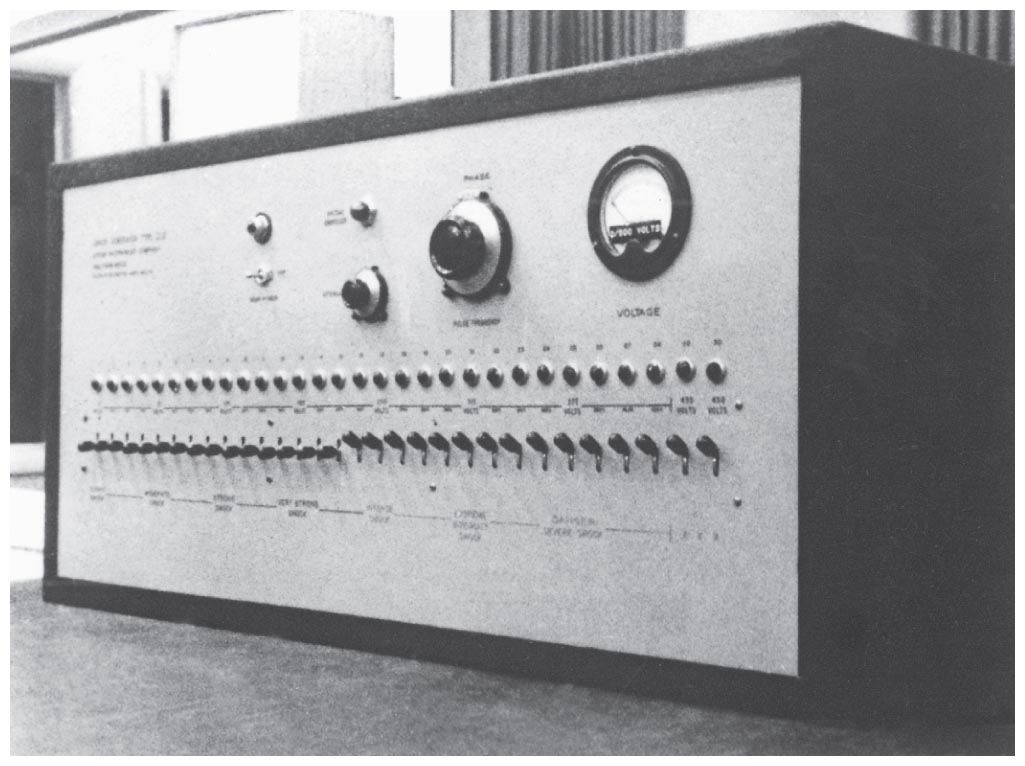

The participant, now in the role of “teacher,” was then instructed to administer shocks—from 15 to 450 volts—to the “learner” each time the learner made an error. Labels under the shock switches ranged from “slight shock” through “danger: severe shock” to “XXX.” The experimenter explained that the teacher was to administer shocks in ascending 15-volt magnitudes: 15 volts the first time the learner made an error, 30 volts the next time, and so on. The teacher was given a 45-volt shock to get a sense of how painful the shocks would be. What he didn’t know was that the learner, who was in another room, was not actually being shocked.

Most participants became concerned as they administered increasingly intense shocks and turned to the experimenter to ask what should be done, but the experimenter insisted they go on. The first time a teacher expressed reservations, he was told, “Please continue.” If the teacher balked, the experimenter said, “The experiment requires that you continue.” If the teacher continued to hesitate, the experimenter said, “It’s absolutely essential that you continue.” If necessary, the experimenter escalated to, “You have no other choice. You must go on.” If the participant asked whether the learner could suffer permanent physical injury, the experimenter said, “Although the shocks may be painful, there is no permanent tissue damage, so please go on.”

In the end, despite the learner’s groans, pleas, screams, and eventual silence as the intensity of the shocks increased, 80 percent of the participants continued past the 150-volt level—at which point the learner mentioned that he had a heart condition and screamed, “Let me out of here!” Fully 62.5 percent of the participants went all the way to the 450-volt level, delivering everything the shock generator could produce. The average amount of shock given was 360 volts, after the learner let out an agonized scream and became hysterical.

This finding surprised Milgram and other experts. A panel of 39 psychiatrists predicted that only 20 percent of the participants would continue past the 150-volt level and that only 1 percent would continue past the 330-volt level. Milgram’s study and its implications are described in more detail in Chapter 9. For now, the important question is: What was it about this situation that led participants to continue applying shocks to a person in obvious pain, possibly causing serious harm? Milgram’s participants were not heartless fiends. Instead, the situation was extraordinarily effective in leading them to do something that would normally fill them with horror. The experiment was presented as a scientific investigation—an unfamiliar situation for most participants. The experimenter explicitly took responsibility for what happened. (Adolf Hitler frequently made similar pledges during the years he marched his nation into a world war and the Holocaust.) Moreover, participants could not have guessed at the outset what the experiment involved, so they were not prepared to resist anyone’s demands. And as Milgram stressed, the step-by-step nature of the procedure was crucial. If the participant didn’t quit at 225 volts, then why quit at 255? If not at 420, then why at 435?

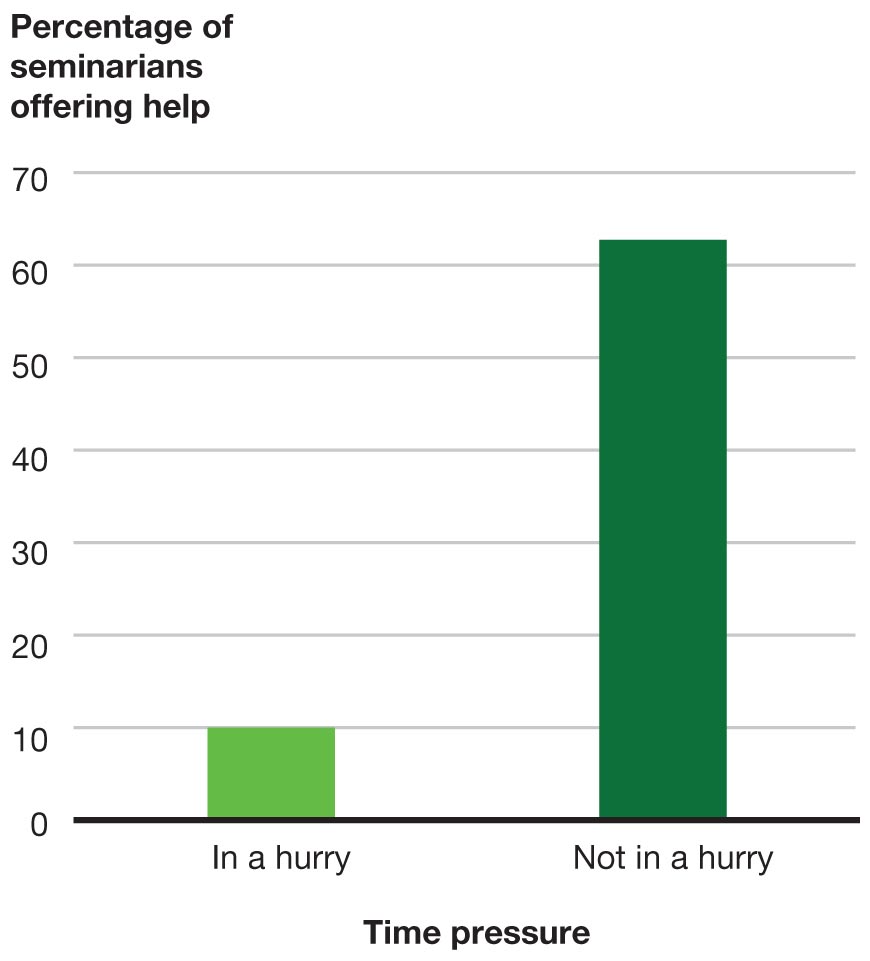

The bar graph depicts the percentage of seminarians offering help to victims when in a hurry and when not in a hurry. The vertical axis represents the percentage of seminarians ranging from 0 to 70 in increments of 10. The data inferred are as follows: In a hurry, 10 percent; Not in a hurry, 63 percent. All values are approximate.

Some ten years after Milgram’s study, a classic experiment by John Darley and Daniel Batson (1973) demonstrated Lewin’s idea of the power of the situation even more simply. In this study, Princeton Theological Seminary students first discussed their religious orientation, reporting on whether they viewed religion primarily as a means toward personal salvation or as a source of moral and spiritual values. Darley and Batson then asked each young seminarian to go to another building to deliver a short sermon. The seminarians were told what route to follow to get there most easily. Some were told that they had plenty of time to arrive at the location for their lecture, and some were told that they were already late and should hurry. On the way to deliver their sermon—on the topic of the Good Samaritan, by the way—each of the seminarians passed a man who was sitting in a doorway with his head down, coughing and groaning and in apparent need of help.

It turned out that the nature of seminary students’ religious orientation was of no use in predicting whether they would offer assistance. But as you can see in Figure 1.1, whether seminarians were in a hurry or not was a very powerful predictor. The seminarians were pretty good Samaritans as a group—but only when they weren’t in a rush.

People are thus governed by situational factors—such as whether they are being pressured by someone or whether they are late—more than they tend to believe. At the same time, internal factors—those that have to do with the kind of person someone is—have less influence than most people assume they do. You may be surprised by many of the findings reported in this book because we tend to underestimate the power of external forces and assume, often mistakenly, that the causes of people’s behavior can be found mostly within them.

Psychologists call internal factors dispositions—that is, beliefs, values, personality traits, and abilities that guide behavior. People tend to think of dispositions as underlying causes of behavior, but that’s not necessarily true. Seeing an acquaintance put a dollar in a donation jar may prompt us to assume that the person is kind, but subsequent observations of the person in different situations might show that we had overgeneralized from a single act. Noticing a stranger in the street behaving angrily, we might assume that the person is aggressive or ill tempered. Such judgments are valid less often than we think.

The failure to recognize the importance of situational influences on behavior, together with the tendency to overemphasize dispositions, is known as the fundamental attribution error (Ross, 1977). The findings of Milgram’s obedience study, the Good Samaritan study, and many others in social psychology suggest that people should consider situational factors when trying to understand other people’s behavior before assuming that the behavior is the result of dispositions. As you read this book, you will become more attuned to situational factors like social norms, the presence of other people, and whether one is with friends or strangers. The ultimate lesson of social psychology is thus a compassionate one. Social psychology encourages us to look at another person’s situation—to try to understand the complex field of forces acting on the individual—in order to fully understand the person’s behavior.

Seventeen years after writing about situationism, Kurt Lewin (1952) introduced the concept of “channel factors” to help explain why certain circumstances that seem unimportant can have great consequences for behavior, either facilitating it or blocking it. Circumstances can guide behavior in a particular direction by making it easier to follow one path rather than another. The concept of channel factors has been borrowed by behavioral economics, a field at the intersection of social psychology and economics. Behavioral economists refer to these factors as “nudges”—small, innocuous-seeming prompts that can have big effects on behavior.

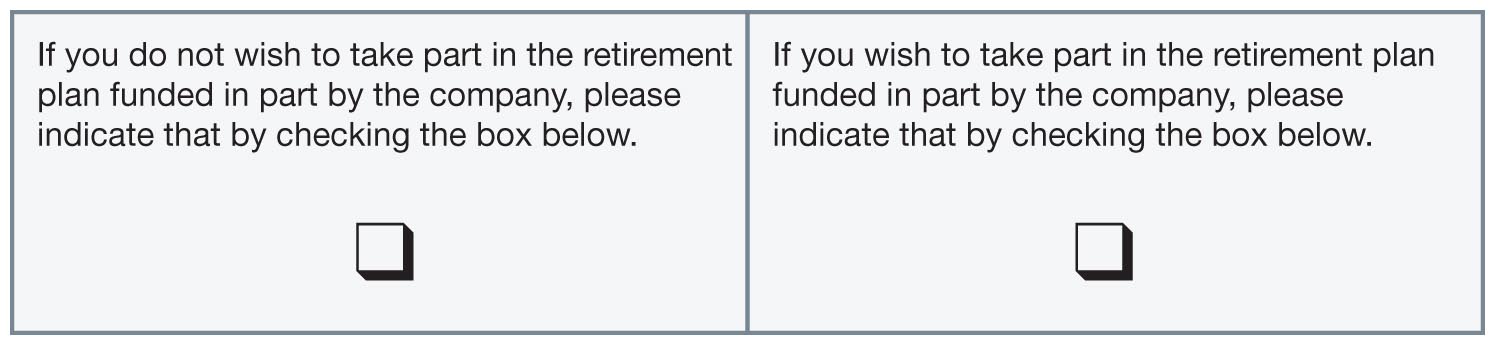

The nudge concept has been applied in many ways. For example, behavioral economists have encouraged businesses to get as many of their employees as possible to participate in savings plans in which the employer puts money away for the employee’s retirement. Rather than have their employees “opt in” to their retirement programs by checking a box or signing a statement saying they do wish to be enrolled, employers create an easy channel for participation by making it automatic. Employees must check a box or sign a statement if they don’t want the retirement plan; otherwise, they are automatically enrolled (Figure 1.2). This modest nudge creates far more participation (and far happier retirements) than when the nudge works against participation (J. Choi, Laibson, & Madrian, 2009; Madrian & Shea, 2001). And did you know that 99 percent of Austrians are registered organ donors, whereas only 12 percent of Germans are? Before you commit the fundamental attribution error and assume that Austrians are simply more generous than Germans, we hasten to tell you that Germans have to check a box if they do want to register as organ donors; Austrians have to check a box if they don’t wish to register as organ donors.

LOOKING BACK

LOOKING BACKSituations are often more powerful in their influence on behavior than we realize. Whether or not people are kind to others and whether or not they act in their own best interests can depend on subtle aspects of the situation. We often overlook such situational factors when we try to understand our own behavior or that of others, and we often mistakenly attribute behavior to presumed dispositions (the fundamental attribution error).