LEARNING OBJECTIVE

- Describe some of the most common difficulties people confront when interacting with members of different racial, ethnic, and religious groups.

Interacting with people who are different from us can be unusually rewarding. They can provide us with fresh perspectives and insights. As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry put it, “He who is different from me does not impoverish me—he enriches me.” As we noted in Chapter 9, encounters with others unlike ourselves can lead to a sense of self-expansion, which people find inherently gratifying (Aron, Aron, & Norman, 2004; Page-Gould & Mendoza-Denton, 2011). Successful or pleasant interactions with people from other demographic groups can also make us feel socially connected, not just to those like ourselves but to humanity in general.

But interacting and having conversations with people who are different from us can also be stressful. When we’re told “don’t talk about money, politics, or religion,” the concern is that trouble will arise from differences in wealth, political conviction, or religious belief. People who are exactly aligned on these dimensions rarely run into conversational trouble.

Indeed, interactions between members of different ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups can be challenging for several reasons. For one thing, the tendency for people to associate disproportionately with people like themselves means that interactions with people from other groups don’t happen as often as within-group interactions do. Their relative rarity, furthermore, can be self-reinforcing. Nicole Shelton and Jennifer Richeson (2005) have shown how White people fear that Black people don’t really want to interact with them, and Black people think the same about Whites, which leads both to hold back and avoid interaction altogether or to act in a stiff, guarded manner that reinforces their original doubts about one another.

A second reason that cross-group interactions can be challenging is that, as when talking about money, politics, or religion, there is often a concern about “stepping in it,” or “stepping on a land mine.” That is, people are often aware of historical or contemporary tensions between their own group and other groups and may fear that those tensions will play out in the here and now of their own interactions. In one study, for example, White participants who were concerned about coming across as prejudiced experienced increases in cortisol, a stress-related hormone, during an interracial interaction (Trawalter et al., 2012). In other studies, when the cardiovascular activity of White participants was monitored during an interaction with a White confederate who belonged to no obvious marginalized group, participants responded physiologically in a manner consistent with their treating the interaction as a challenge—a response that’s physiologically benign. But when interacting with either a Black confederate, someone thought to be socioeconomically disadvantaged, or someone with a prominent facial birthmark, the participants’ cardiovascular profile was more reflective of the experience of threat, a more toxic physiological reaction (Blascovich et al., 2001; Mendes et al., 2002).

In addition to a general fear that things won’t go well in interactions with people from other racial, ethnic, religious, or socioeconomic groups, people experience more specific fears tied to their knowledge about what others might think about the groups to which they belong. Because of the history of slavery in the United States—and the more than 150 years of mistreatment of Black Americans afterward—White Americans are often concerned about not coming across as racist when interacting with Black people (C. S. Crandall & Eshleman, 2003). And, as one would expect from the stereotype content model discussed earlier in this chapter, this often plays out as White people being concerned with being liked. As the dominant social group in the United States, they assume that others don’t doubt their competence, but they know that their warmth, kindness, and morality may be in question. Members of marginalized groups, however, worry that others may question their competence, so they enter intergroup interactions wanting to be respected. These divergent concerns have been documented both in the explicit interaction goals expressed by White and non-White participants and in their actions during cross-race exchanges (Bergsieker, Shelton, & Richeson, 2010).

An intriguing side effect of the concern with being liked can be seen in White liberals’ behavior during interracial interactions. They shy away from using expressions of competence in their language—or, as the investigators put it, they “downshift” their language—when interacting with people of color, inadvertently acting in something of a patronizing manner (Dupree & Fiske, 2019). For example, when asked to select adjectives to describe themselves to someone with a White-sounding name, liberal Whites chose words like assertive and competitive that connote competence. But when describing themselves to someone with a Black-sounding name, they chose words like supportive and compassionate that connote warmth. More conservative White participants did just the opposite. An examination of speeches delivered by Democratic and Republican candidates for president since 1992 uncovered a similar pattern: The more liberal Democratic candidates, but not their Republican rivals, used less competence-related language when speaking to audiences consisting largely of people of color than they did when speaking to largely White audiences.

A series of follow-up studies revealed a complementary competence upshift on the part of Black and Hispanic conservatives (Dupree, 2021). For example, in their speeches to Congress, which remains a mostly White body, conservative Black and Hispanic politicians emphasize competence more than their more liberal Black and Hispanic peers do. In another study, Black participants were asked to create an online profile of themselves, ostensibly to present to another participant. An analysis of the content of their profiles revealed that conservative Black respondents who thought they were interacting with a White person emphasized high status more than their liberal peers did. Tellingly, conservative and liberal Black respondents did not differ in their self-presentations when they thought they were interacting with a Black person.

Interacting with members of other groups is not always stressful, of course. We often get swept up in a joint task that needs completing, a drama unfolding in film or on television, or the details of compelling conversation and lose any sense of self-consciousness. But unpleasantness and self-consciousness lurk in other contexts and on other topics. Sometimes the tension results from anticipating disagreement—for example, if Donald Trump and Joe Biden voters were to discuss the 2020 election or if CNN and Fox News viewers were to talk about COVID-19 vaccinations. But other times, tension arises from the fear that we’ll say the wrong thing or that what we say will be misconstrued—as, for example, when cisgender and trans people discuss public bathrooms or when Arab and Jewish Americans discuss the Middle East.

In one study that highlights the contextual nature of anxieties about intergroup interactions, White participants who thought they were about to interact with either two White or two Black fellow participants were asked to arrange three chairs for the conversation.

DATA EXPLORATION

They did so such that they would be farther away from their Black conversation partners when they thought they would be discussing racial profiling than when they thought they’d be discussing love and relationships. The anticipated topic of conversation had no impact on the distance they placed between the chairs when they thought they were going to interact with White partners (Goff, Steele, & Davies, 2008; Figure 11.8).

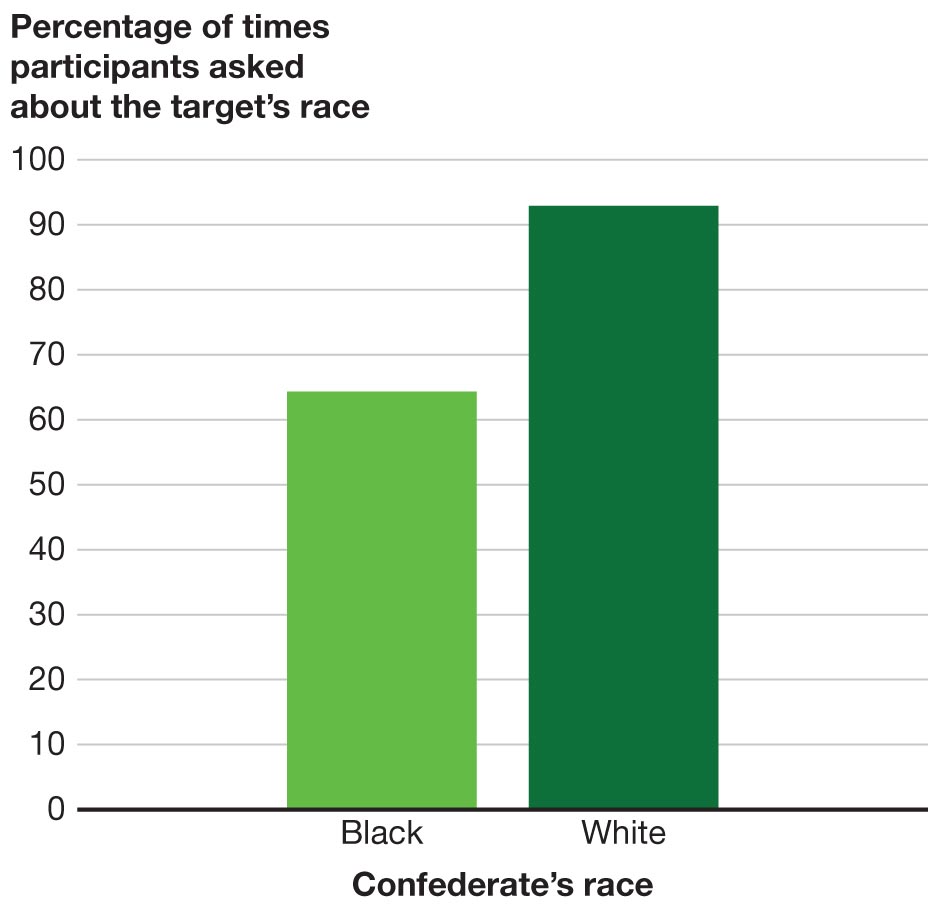

Michael Norton and colleagues conducted an especially illuminating investigation of the anxieties that can attend interracial interactions. The researchers had White participants play a game similar to the children’s game Guess Who with either a Black or White confederate (Norton et al., 2006). Each participant’s task was to ask the confederate a series of yes-or-no questions about a set of photographs and to identify, with as few questions as possible, which target photo the confederate was looking at. Half the photos were of men and half were of women; half were presented with a red background and half with a blue background; and half were of Black individuals and half were of White people. You might be able to anticipate the result of this study by consulting your own anxiety and carefulness in some interracial interactions: The participants were significantly less likely to ask about the race of the target person when they were interacting with a Black confederate (see Figure 11.9).

A follow-up study used a variant of this same paradigm but with children as participants. In one version of the game, in which all the target photos were White, the older children, as one would expect, performed better than the younger children did (that is, they needed fewer questions to identify the correct target photo). But when some of the target photos were of Black people, the older children performed worse than their younger counterparts. The older children had apparently picked up on sensitivities surrounding the topic of race, which the younger children were still innocently unaware of (Apfelbaum et al., 2008).

The graph depicts the anxiety about intergroup interactions, which shows the percentage of times participants asked about the target’s race for Black and White confederates. The vertical axis represents the percentage of times participants asked about the target’s race, ranging from 0 to 100 in increments of 10. The data inferred are as follows: Confederate’s race is black, 65; Confederate’s race is white: 92. All values are approximate.

These studies highlight the difficulties that members of both majority and minority groups can experience in intergroup interactions. Many times, however, such difficulties weigh more heavily on the members of marginalized groups. In one especially telling study of how the biases that play out in intergroup interactions can harm those in marginalized groups, a group of economists examined the performance of cashiers in 34 outlets of a large French grocery chain, some of whom had traditionally French-sounding names and some of whom had names associated with North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa (Glover, Pallais, & Pariente, 2017). The cashiers were quasi-randomly assigned to work on some days for managers who were known to be biased toward Africans, as assessed by their responses to the Implicit Association Test (see Chapters 6 and 10), and on other days for managers who weren’t known to be biased. The cashiers with African names outperformed their French-named peers on days when they were working for unbiased managers (which the investigators took to be evidence that the grocery chain set a higher bar for hiring non-European cashiers—only the very best of them were hired, whereas less talented or less hardworking French applicants were given jobs). But when working for the biased managers, the African-named cashiers, but not their French-named counterparts, scanned items more slowly and spent less time at work. The investigators ascribed these differences to the biased managers interacting less with their African-named cashiers, which set in motion a self-fulfilling prophecy whereby the managers’ low expectations about these cashiers were reinforced by the cashiers actually exerting less effort.

A final note about biases in intergroup interactions, this one on display in popular media for anyone to see: Max Weisbuch and colleagues examined the interactions between equal-status White and Black characters on 11 popular television shows (Weisbuch, Pauker, & Ambady, 2009). Recordings of these interactions were edited so that one of characters, sometimes a White character and sometimes a Black one, was off screen, and the audio was removed. These edited interactions were then shown to a group of undergraduates who were asked to rate how well the unseen characters were treated by the person (or persons) on screen and how well-liked the unseen character was. Off-screen Black characters were judged to be less well-liked and treated more poorly by the on-screen characters than off-screen White characters were. It’s hard to know what effect a steady television diet of Black characters being subtly depicted in a negative light might have, but it’s hard to imagine that it’s positive.

LOOKING BACK

LOOKING BACKPeople sometimes experience tension and awkwardness when interacting with members of outgroups, feelings that show up as physiological markers of stress during such interactions. Adding to the tension is that each group often assumes that those in the other group don’t want to interact with them. Members of a number of marginalized groups, furthermore, often worry about being stereotyped as less competent than majority-group members. Majority-group members often have the complementary worry about seeming cold. This leads politically liberal Whites to “downshift” their use of competence-related language in an effort to be liked, which can come across as patronizing. Black and Hispanic political conservatives often do the opposite, using more competence- and status-related language when interacting with White peers.