LEARNING OBJECTIVE

- Distinguish between basic and applied research and explain how the findings of each contribute to the other.

The practice of scientific research has two broad types: basic and applied. Basic science (or basic research) is concerned with trying to understand some phenomenon in its own right, rather than using a finding to solve a particular real-world problem. Basic scientific studies are conducted with a view toward using the findings to build valid theories about the nature of some aspect of the world. For example, social psychologists investigating people’s obedience to an authority figure in the laboratory are doing basic science in an attempt to understand the nature of obedience and the factors that influence it. They’re not trying to find ways to make people less obedient to dubious authorities, though they may hope that their research is relevant to such real-world problems.

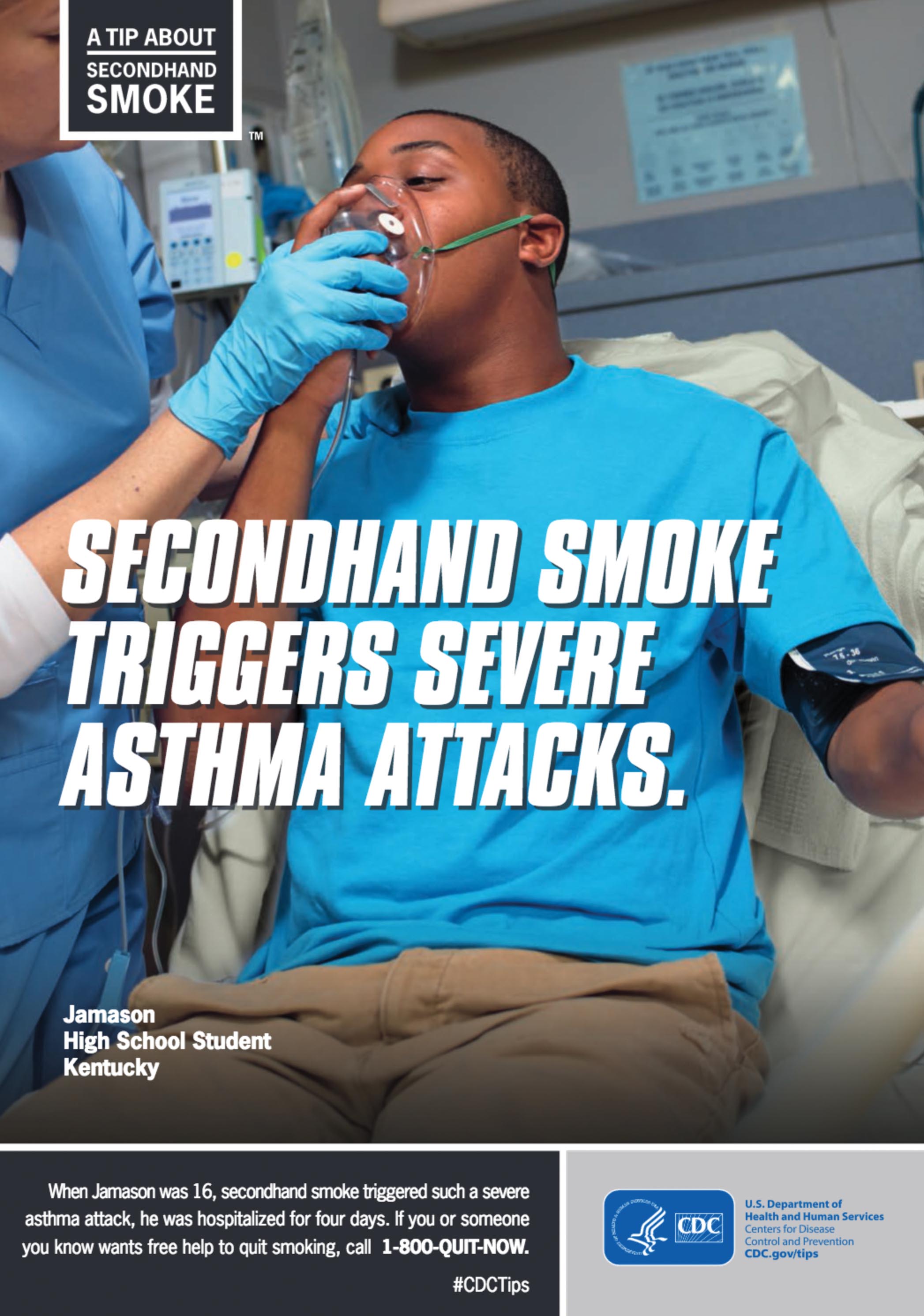

The ad poster features Jamason, a high school student from Kentucky, sitting on a hospital bed. A nurse helps him to wear an oxygen mask over his mouth and nose. A text on the poster reads, “Secondhand smoke triggers severe asthma attacks.” The logo of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U S Department of Health and Human Services, is at the bottom right.

Applied science (or applied research) is concerned with solving a real-world problem of importance. An example of applied research in social psychology would be a study of how to make preteens less susceptible to cigarette advertising. (One way is to make them aware of tobacco companies’ motives and their cynical desire to get teens to do something that is not in their best interests.)

There is a two-way relationship between basic and applied research. Basic research can give rise to theories that may lead to interventions, or efforts to change certain behaviors. For example, social psychologist Carol Dweck and her colleagues found that people who believe that intelligence is the product of sustained hard work study harder in school and get better grades than people who believe that intelligence is a matter of genes (that is, people who think you’re either intelligent or not, and you can’t do much to change it; Dweck, Chiu, & Hong, 1995). Her basic research on the impact of beliefs about intelligence on school performance prompted her to design an intervention with Black and Hispanic junior high students. She told some of them that their intelligence was under their control and gave them information about how working on school subjects actually changes the physical nature of the brain (Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, 2007; Henderson & Dweck, 1990). Those students worked harder and got better grades than students who were not given such information.

The direction of influence can also go the other way: Applied research can produce results that feed back into basic science. For example, applied studies during World War II on how to produce effective war propaganda led to an extensive program of basic research on attitude change. That program, in turn, gave rise to theories of attitude change and social influence that continue to inform basic science and to generate new techniques of changing attitudes in applied, real-world contexts.

LOOKING BACK

LOOKING BACKBasic science attempts to discover fundamental principles; applied science attempts to solve real-world problems. There is an intimate relationship between the two: Basic science can reveal ways to solve real-world problems, and applied science aimed at solving real-world problems can give rise to the search for basic principles that explain why the solutions work.