Populism and Mainstream Politics

Though socialism remained mostly at the political fringes even as it gained steam, Populism entered American politics at the end of the nineteenth century, and it never left. It pitted “the people,” meaning everyone but the rich, against corporations, which fought back in the courts by defining themselves as “persons,” accorded the due process protections provided in the Fourteenth Amendment. And it pitted “the people,” meaning white people, against nonwhite people who were fighting for citizenship rights, and whose ability to fight back in the courts was far more limited, since those fights require well-paid lawyers.

Political Science and the State

Populism also pitted the people against the state. During populism’s initial rise, the state as a political entity became an object of formal academic study through political science, one of a new breed of academic fields known as the social sciences. Before the Civil War, most American colleges were evangelical; college presidents were ministers, and every branch of scholarship was guided by religion. After 1859 and publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, the rise of the theory of evolution contributed to the secularization of the university. So did the influence of the German educational model, in which universities were divided into disciplines and departments, each with a claim to secular, and especially scientific, expertise. These social sciences—political science, economics, sociology, and anthropology—used the methods of science, and especially of quantification, to study history, government, the economy, society, and culture.

Political scientists, by examining the powers of the state, formed a bridge between the populist and progressive movements. Columbia University opened a School of Political Science in 1880, the University of Michigan in 1881, Johns Hopkins in 1882. Woodrow Wilson completed a PhD in political science at Johns Hopkins in 1886. He planned to write a “history of government in all the civilized States in the world,” to be called The Philosophy of Politics. In 1889, he published a preliminary study called, simply, The State. For Wilson’s generation of political scientists, the study of the state replaced the study of the people. The erection of the state became, in their view, the greatest achievement of civilization. The state also provided a bulwark against populism. In the first decades of the twentieth century, populism would yield to progressivism as urban reformers applied the new social sciences to the study of political problems, to be remedied by the intervention of the state.

The Invention of the Journalist

The rise of populism and the social sciences reshaped the press, too. In the 1790s, the weekly partisan newspaper had produced the two-party system. The penny press of the 1830s had produced the popular politics of Jacksonian democracy. And in the 1880s and 1890s, the spirit of populism and the empiricism of the social sciences drove American newspapers to a newfound obsession with facts.

The “journalist,” like the political scientist, was an invention of the 1880s. The Journalist, a trade publication that identified journalism as a new profession that shared with the social scientist a devotion to facts, began appearing in 1883, the year Joseph Pulitzer took over the New York World. Pulitzer, a Hungarian immigrant who didn’t know a word of English when he arrived in the United States, had served in an all-German regiment in the Civil War; after the war, he studied law in St. Louis and began working for a German-language newspaper. He would make the World into one of the nation’s most influential papers. “A newspaper relates the events of the day,” Pulitzer said. “It does not manufacture its record of corruptions and crimes, but tells of them as they occur. If it failed to do so it would be an unfaithful chronicler.”

William Randolph Hearst began publishing the New York Journal in 1895. Hearst, born to great wealth in 1863 (his father had struck gold in California), had taken over his father’s paper, the San Francisco Examiner, in 1887, after dropping out of college. In 1896, Adolph Ochs, the son of a Bavarian immigrant and lay rabbi, took over the New York Times. Ochs, raised in Tennessee, had started his career in newspapers by delivering the Knoxville Chronicle at the age of eleven; he left school three years later. He was thirty-eight when he bought the Times and pledged his intention to publish “without fear or favor.”

The newspapers of the 1880s and 1890s were full of stunts and scandals and crusades. Front pages were splashed with sensational headlines, designed to stir readers’ passions with outsized tales, and where crime was concerned, the goriest of details. Nevertheless, more and more, newspapers defended their accuracy. “Facts, facts piled up to the point of dry certitude was what the American people really wanted,” wrote the reporter Ray Stannard Baker. Julius Chambers said that writing for the New York Herald involved “Facts; facts; nothing but facts. So many peas at so much a peck; so much molasses at so much a quart.” A sign at the Chicago Tribune in the 1890s read: “WHO OR WHAT? HOW? WHEN? WHERE?” The walls at the New York World were covered with printed cards: “Accuracy, Accuracy, Accuracy! Who? What? Where? When? How? The Facts—The Color—The Facts!”

More information

An overhead view of a massive convention crowd. The rafters of the roof above are festooned with flags.

“A Cross of Gold”

At the Democratic National Convention in 1896, twenty thousand people witnessed the electrifying speech of William Jennings Bryan, soon to be the party’s presidential nominee.

In 1895, Pulitzer’s New York World endorsed Mary Lease as candidate for mayor of Wichita. After she lost and her home in Wichita was foreclosed, she moved to New York and decided it was “the heart of America.” She campaigned for Henry George, who was running for mayor. It looked as though he had a chance, but he died in his bed of a stroke five days before the election. His body lay in state at Grand Central Station. More than 100,000 mourners came to pay their respects. Lease delivered a eulogy. The New York Times reported, “Not even Lincoln had a more glorious death.”

Free Silver and a Cross of Gold

In the summer of 1896, William Jennings Bryan, a man Ochs’s New York Times called an “irresponsible, unregulated, ignorant, prejudiced, pathetically honest and enthusiastic crank,” chugged across the plains in a custom railroad coach called the Great Nebraska Silver Train, which was decorated with giant signs that read “Keep Your Eye on Nebraska.” He was heading for Illinois, to the Democratic National Convention at the Chicago Coliseum, a three-story building that took up an entire city block, where he would deliver one of the most effective and memorable speeches in American oratorical history.

Bryan, in his baggy pants and black alpaca suit, had come to Chicago to fuse the People’s Party into the Democratic Party, to turn the party of white southerners into the party, as well, of western farmers and northern factory workers, leaving the Republican Party to be the party of businessmen. The wind was at Bryan’s back. The Democratic Party had for the first time endorsed an income tax, “so that the burdens of taxations may be equally and impartially laid, to the end that wealth may bear its due proportion of the expenses of the Government.” Bryan had also become the leading national spokesman of the Free Silver movement: for decades, western farmers had urged the unlimited coining of silver money, which they thought would raise the price of their crops and make it easier for people in debt to pay their creditors. Accepting Bryan as its presidential candidate would be a far greater step for the Democratic Party than adding a plank to its platform.

More information

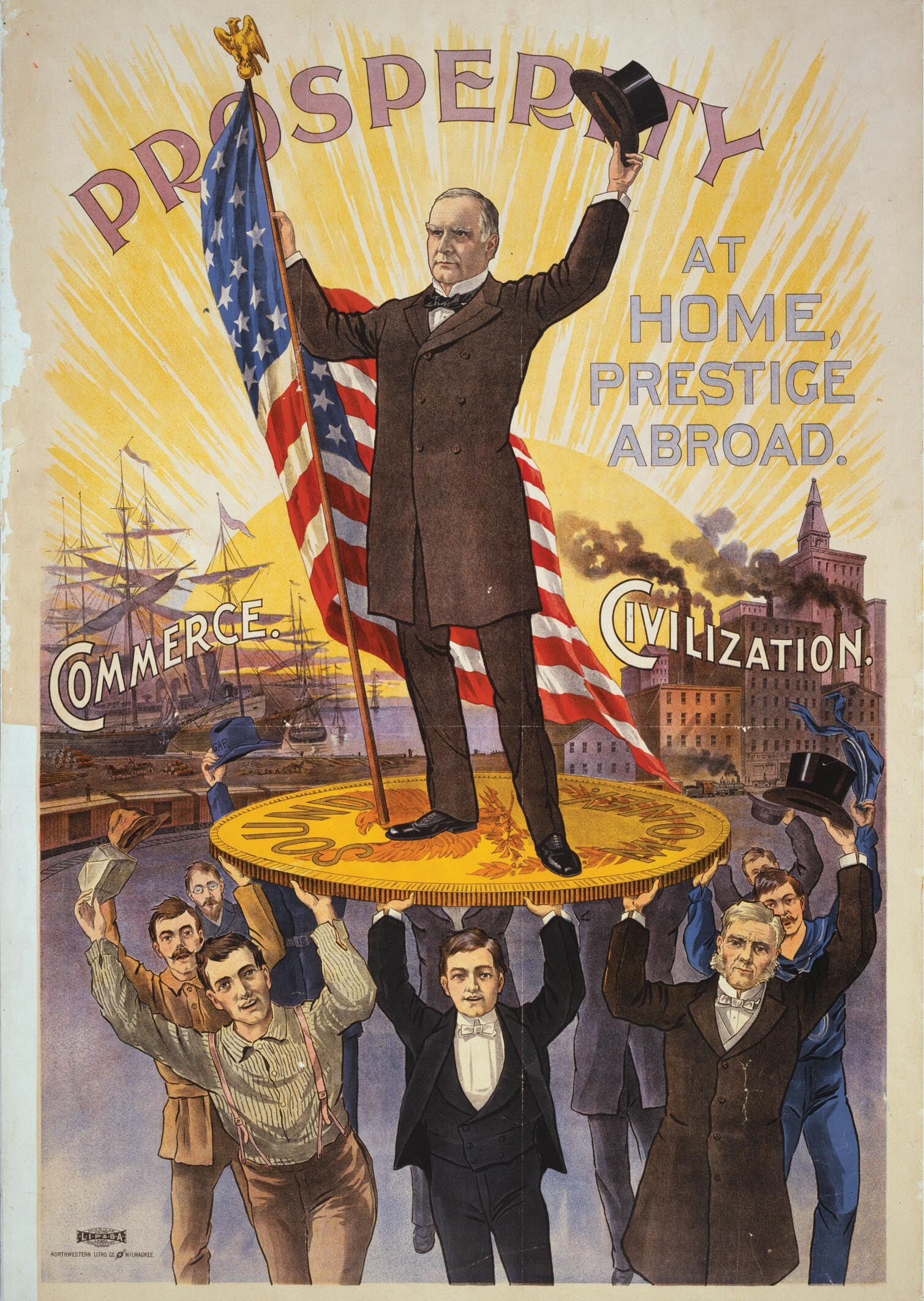

A color poster for the McKinley campaign. The candidate holds an American flag while standing atop an enormous gold coin that is being supported by stalwart citizens from all walks of life. Above and beside McKinley is the slogan Prosperity at Home, Prestige Abroad. To his right and left are the words Commerce and Civilization.

A Money Campaign

Funded by Republican businessmen and bankers, William McKinley’s presidential campaign defended the gold standard and corporate interests.

Bryan leapt to the stage. “I come to speak to you in defense of a cause as holy as the cause of liberty,” he said, “the cause of humanity.” The struggle between business and labor had been misunderstood, he argued, and rested on too narrow a definition of business. The people are “a broader class of businessmen”: “The man who is employed for wages is as much a business man as his employer,” Bryan said. “The farmer who goes forth in the morning and toils all day . . . and who by the application of brain and muscle to the natural resources of the country creates wealth, is as much a business man as the man who goes upon the board of trade and bets upon the price of grain.” Opposing the gold standard, the Republican Party’s central economic policy, Bryan brought together his Jeffersonianism with his revivalist Christianity. “There are two ideas of government. There are those who believe that, if you will only legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, their prosperity will leak through on those below. The Democratic idea, however, has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous, their prosperity will find its way up through every class which rests upon them.” (Bryan here offered an early indictment of what, nearly a century later, during the presidency of the Republican, Ronald Reagan, would come to be known as “trickle-down economics.”)

As he closed, hollering to a crowd more than twenty thousand strong, he placed upon his head an imaginary crown of thorns: “We will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns.” He stretched his arms wide and bowed his head. “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” And then he shut his eyes and fell as still as death.

“My God! My God! My God!” the crowd began to chant. They took off their hats and threw them up in the air. Those who didn’t have hats took off their coats and threw them instead. Anyone who had an umbrella opened it. “Under the spell of the gifted blatherskite from Nebraska,” a reporter for the New York Times wrote, “the convention went into spasms of enthusiasm.”

Bryan, a big, bellowing man, was much mocked, especially in the big cities of the East, by newspapers favorable to business interests. The Times ran the headline, “The Silver Fanatics Are Invincible: Wild, Raging, Irresistible Mob Which Nothing Can Turn from Its Abominable Foolishness.” Even Joseph Pulitzer’s far more man-of-the-people World refused to endorse Bryan. Populists, meanwhile, feared that fusion would destroy their movement. “We will not crucify the People’s Party on the cross of Democracy!” said one delegate from Texas.

The Election of 1896

But, in the end, the People’s Party threw its support behind Bryan, mounting no candidate of its own. Even Mary Lease gave him her grudging endorsement. At the People’s Party convention in St. Louis, she seconded his nomination. And socialists supported him. Eugene Debs wrote to Bryan, “You are at this hour the hope of the Republic.”

Bryan ran against Republican former Ohio governor William McKinley, who represented the interests of businessmen and ran armed with a war chest of donations made by banks and corporations terrified of the possibility of a Bryan presidency. Ballot reform, far from keeping money out of elections, had ushered more money into elections, along with a new political style: using piles of money to sell a candidate’s personality, borrowing from the methods of business by using mass advertising and education, slogans and billboards. McKinley ran a new-style campaign; Bryan ran an old-style campaign, undertaking, nationally, the kind of campaigning that had only ever before been done in local elections. Bryan barnstormed all over the country: he gave some six hundred speeches to five million people in twenty-seven states and traveled nearly twenty thousand miles.

More information

Thirteen women in identical white dresses with matching white caps pose with a poster portrait of William Jennings Bryan. Some of them hold small American flags.

Women in Politics

Although women would not secure the national right to vote until 1919, their political activism proved critical at the turn of the century. Here, a group of women campaign for William Jennings Bryan.

But McKinley’s campaign coffers were fuller: Republicans spent $7 million; Democrats, $300,000. John D. Rockefeller alone provided the GOP with a quarter of a million dollars. McKinley’s campaign manager, Cleveland businessman Mark Hanna, was nearly buried in donations from fellow businessmen. He used that money to print 120 million pieces of campaign literature. He hired 1,400 speakers to stump for McKinley; dubbing the Populists “Popocrats,” they agitated voters to a state of panic. As Mary Lease liked to say, money elected McKinley. Lease, disgusted by the election, left Populism behind in favor of journalism: Pulitzer hired her as a reporter.

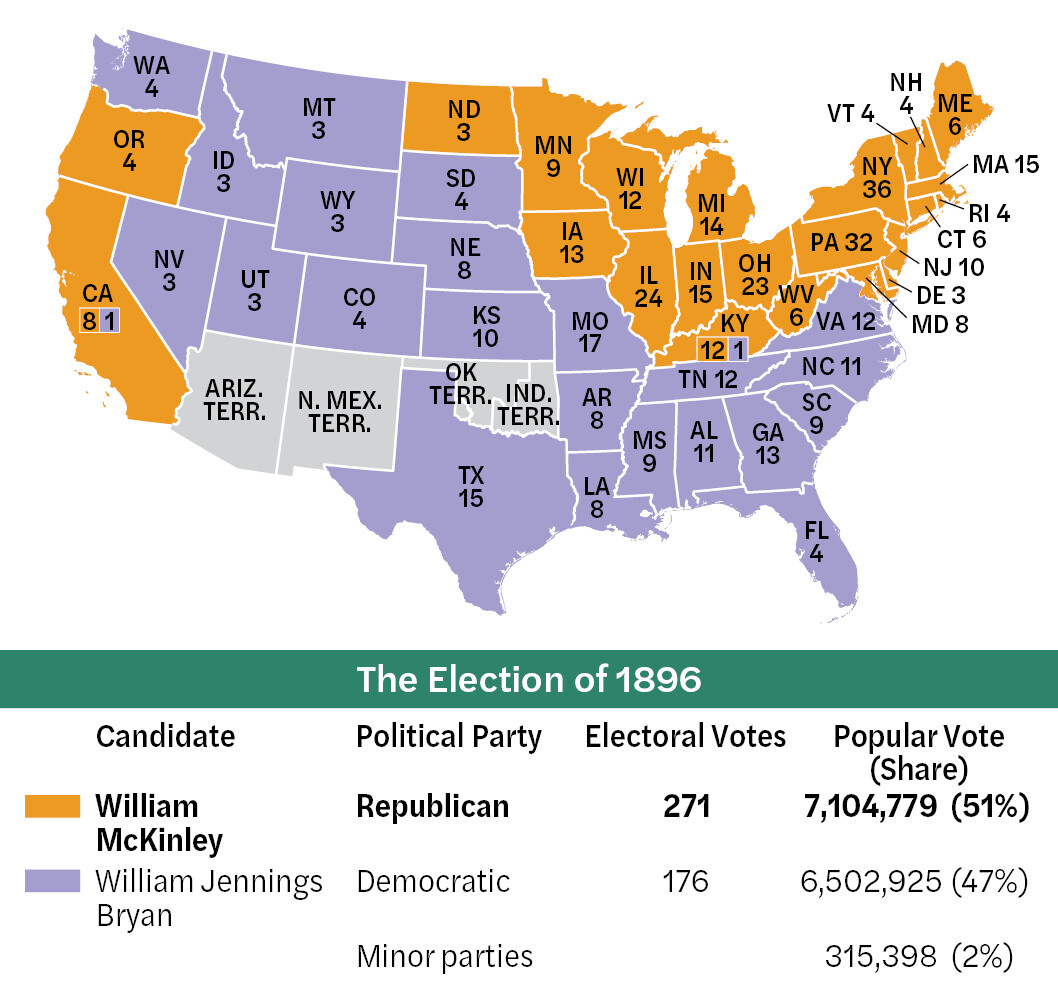

On Election Day, nine out of ten American voters cast secret, government-printed ballots. McKinley won, with 271 electoral votes to Bryan’s 176. Black men hardly voted; women and Chinese Americans not at all. But for the first time in decades, no one was killed at the polls. Bryan and his wife collected clippings and published a scrapbook. They called it The First Battle.

More information

A map showing the results of the presidential election of 1896. William McKinley, a Republican, won, gaining 51% of the popular vote and winning 271 electoral votes in California, Washington, North Dakota, the Midwest, Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and the Northeast. William Jennings Bryan, a Democrat, was the winner in the remaining states, in the West and the South. He finished with 176 electoral votes and 47% of the popular vote. Minor parties accounted for the remaining 2%.

Only after Bryan’s defeat did Debs, who had endorsed Bryan, abandon his earlier devotion to the two-party system. On January 1, 1897, in the Railway Times, Debs announced he had become a socialist. “The result of the November election has convinced every intelligent wageworker that in politics, per se, there is no hope of emancipation from the degrading curse of wage slavery,” he wrote. “I am for socialism because I am for humanity. . . . Money constitutes no proper basis for civilization.” That June, at the annual meeting of the American Railway Union, Debs founded the Socialist Democracy of America. Within the year, it had splintered, with Debs heading what became the Socialist Democratic Party, later the Socialist Party of America.