THE MIGRATIONS OF HOMO SAPIENS

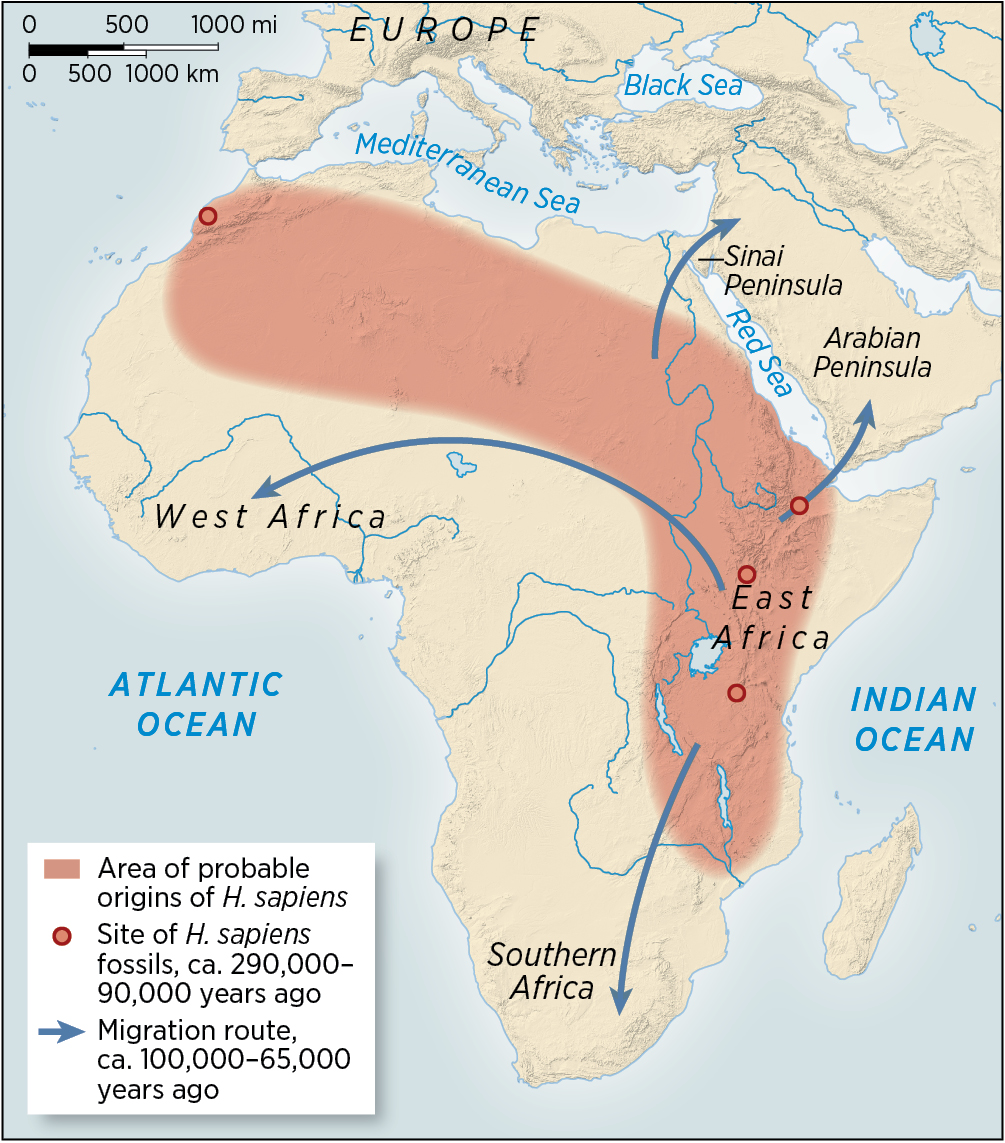

We—the last of the hominins—are an upstart species. The fossil and genetic evidence suggests that our species appeared between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago in North and East Africa. We are also wanderers. Within Africa, groups of Homo sapiens migrated south, starting more than 80,000 years ago. Others went west a little later. These wandering groups had spread out over Africa by 25,000 years ago. In the thinly populated continent, some groups became isolated from the rest for thousands of years, which helps explain why African populations today exhibit greater genetic diversity than all other humans combined.

OUT OF AFRICA

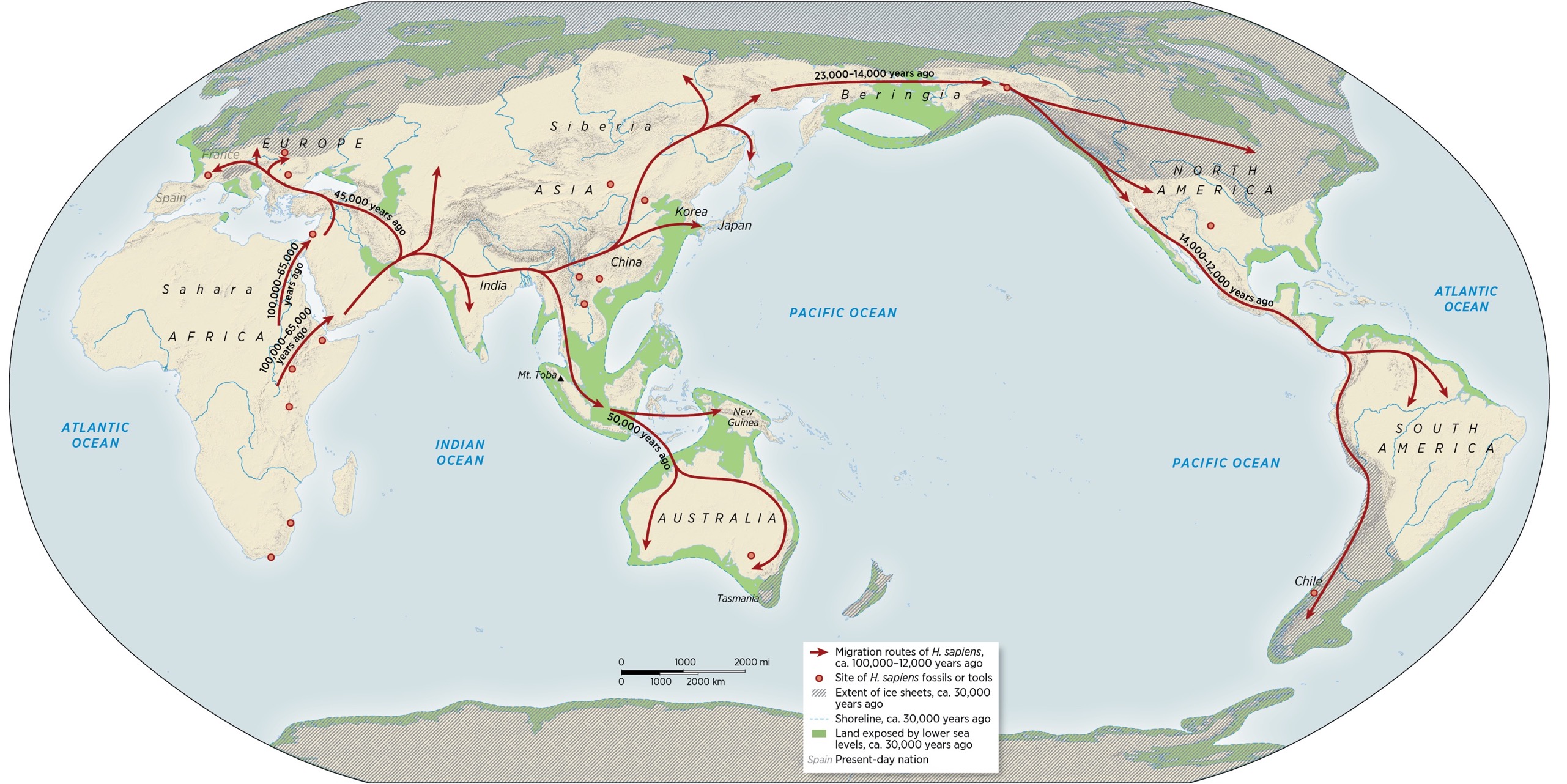

At some point between 100,000 and 65,000 years ago, other wandering Homo sapiens trekked out of Africa and began to colonize parts of Eurasia. A run of dry weather in northeastern Africa about 74,000 to 60,000 years ago might have motivated them to try their luck further afield. There is as yet no archeological evidence speaking directly to this migration. But somehow they traveled, either on foot via Egypt and the Sinai Peninsula or by island-hopping across the southern Red Sea to the Arabian Peninsula. In those Ice Age days, sea level was much lower than today and the Red Sea less of a barrier. Once the wanderers crossed to Asia, they seem to have headed along the shorelines eastward toward India. They then split up and spread out.

One set of human migrants drifted eastward. They soon reached New Guinea and Australia, landmasses that were then united as a single continent owing to the lower sea level of the Ice Age. Getting there from the Asian mainland still required a sea journey of at least 60 miles (100 km). This voyage implies a considerable technological and logistical competence, as well as high tolerance for risk. The first Australians were surely a plucky lot. They continued on southward to Tasmania by about 40,000 years ago, but stopped short of Antarctica, leaving it uninhabited.

Other Homo sapiens entered Europe from southwestern Asia around 45,000 years ago. These new Europeans, according to genetic evidence, are the ancestors of 75 to 85 percent of contemporary Europeans. They soon encountered the depths of the last ice age and—not unlike their more affluent descendants today—headed for Spain and southern France in search of balmier climes. Other human groups walked into the frigid expanse of Siberia, attracted by the abundance of large, tasty mammals such as woolly mammoths, whose hides were as useful as their meat. Groups of humans also headed into what is now China and Japan, arriving about 30,000 years ago.

Some people moved still further afield. The last chapter in these epic migrations brought people to the Americas—possibly as early as 23,000 years ago, certainly by 14,000 years ago. They came to Alaska from Siberia via a broad land bridge exposed by the lower sea levels. They might have walked across it, or perhaps paddled rafts along its southern coast. Once in the Americas, they apparently spread out quickly, reaching Chile no later than 12,000 years ago. The archeological, linguistic, and DNA evidence concerning the human discovery of America is not consistent, so arguments rage about its timing, the size of the founding population, and whether they came all at once or in several separate waves. It does seem that the first Americans are most closely related to peoples of southern Siberia, although rival interpretations maintain their cousins were from what is now Korea and northern China.

These long, slow migrations out of Africa and throughout the world no doubt experienced many setbacks. As of roughly 50,000 to 75,000 years ago, the total human population in all of Africa and Eurasia was probably only a few hundred thousand—fewer people than live today in Wyoming or Newfoundland. It was an uncrowded world in which people rarely encountered strangers. It was full of lethal risks too. Some migrating groups guessed wrong and found themselves in deserts. Others attempted what they thought was a short sea voyage and never saw land again. But slowly, in fits and starts, humankind colonized the globe.

THE ROLE OF CLIMATE

Human colonization of the globe took place during the last ice age, which lasted roughly from 130,000 to 12,000 years ago. Cold, dry, and fickle climate presented our ancestors with strong reasons to move around.

The Earth’s climate has always been changing. For the past 3 million years or so, climate has periodically entered long cold spells that last on average 100,000 years or more. These ice ages were punctuated by brief interglacial periods lasting generally a mere 10,000 years. An ice age typically brought great expansions of polar ice sheets and mountain glaciers, colder temperatures everywhere, and dryer conditions in most places. The ice age that began around 130,000 years ago hit a particular cold snap starting about 24,000 years ago; today’s Chicago and Glasgow were under ice sheets thicker than skyscrapers are tall. That big chill ended abruptly about 12,000 years ago.

The last ice age was not only much colder and dryer than modern climate, but also far more unstable. Periods of sudden cooling or warming might occur, with swings of 9 to 18 degrees Fahrenheit (5 or 10 degrees Celsius) over a few centuries. The slender evidence suggests these swings were smaller in Africa than elsewhere. But everywhere the incentives to migrate, either to avoid the worst of the cold and drought or to take advantage of warming and moisture, were often strong.

With so much water frozen into ice sheets, our wandering ancestors enjoyed the advantage of lower sea levels during the Ice Age. This gave people more land to work with—the equivalent of a bonus continent the size of North America. It was possible to walk from Korea to Japan, from Britain to France, or, as we’ve seen, from Siberia to Alaska.

The most challenging moment of the last ice age came around 75,000 years ago when a giant eruption occurred at Mount Toba, a volcano in what is now Indonesia. The eruption spewed enough dust and ash into the skies to block sunlight for years, and it may have lowered global temperatures by 10 to 30 degrees Fahrenheit (5 to 15 degrees Celsius). It’s likely that this catastrophe played havoc with plant and animal life, and it may have brought the human species close to extinction: DNA evidence suggests that at around this time our ancestors’ numbers were reduced to 10,000 or so—only a little more than the populations of endangered species such as pandas or tigers today. The Toba event was unique. But the last ice age contained numerous cold spells and severe droughts, a circumstance that surely rewarded migration, innovation, learning, and communication.

GENETIC AND CULTURAL DIVERSITY

The experience of migration to all the continents except Antarctica during a time of cold and fickle climate changed Homo sapiens. It made our ancestors more diverse, both genetically and culturally.

Recall that by moving around within Africa, the small populations of early Homo sapiens often separated themselves from one another. As with all species whose populations fragment into isolated groups, early Homo sapiens within Africa underwent considerable genetic diversification, with each small population adapting genetically to its local environment. That process of diversification continued in the small group or groups that left Africa for Asia and Europe. They also spread out, grew isolated from one another, and diversified enough genetically so that humans eventually developed a range of skin, hair, and eye colors. Their body shapes also diversified. People who lived in colder places benefited from being stockier (as had Neanderthals), because a stocky build retains heat more efficiently than a lean one. Others who lived at high elevations developed genetic adaptations to a low-oxygen environment.

The genetic diversity of the entire non-African human population, however, remains smaller than that among Africans themselves, a result of what in population genetics is called a founder effect. All non-African peoples of the world are descended from a few groups of African emigrants—probably (to judge by genetic evidence) between 600 and 10,000 people. So despite all the globe-trotting that took people to places as far apart as Europe, Australia, and the Americas, people of non-African descent today remain less genetically diverse than Africans.

The opposite proved true with respect to cultural evolution because culture can change faster than genomes. The variety of environments that those emigrants from Africa encountered stimulated changes in culture. By 30,000 years ago, people outside of Africa had developed more diverse behaviors and tool kits than were found within Africa. For example, people needed more clothing when they got to higher latitudes, so they learned how to use animal furs and skins to keep warm. They learned how to sew small bits of fur into big patchwork cloaks. They also found in most of Eurasia, especially its chillier parts, that there were fewer nutritious plants to gather than in warmer climates, but that hunting big game was far easier. The big animals in Africa had had time to evolve defenses against clever, fire-wielding, spear-throwing team players, because humans took so long to develop these skills. So animals there instinctively kept their distance from Homo sapiens. But outside of Africa, big animals had no such experience, so they naively allowed humans to approach and surround them. As a result, people outside of Africa often developed cultures with a larger role for big-game hunting and a smaller role for gathering roots, nuts, and berries. Artistic styles and the variety of languages spoken multiplied outside of Africa. So our ancestors’ wanderings after leaving Africa led eventually to vast cultural diversity among peoples with only modest genetic diversity.

This saga of cultural, and to a lesser extent genetic, diversification as people spread out across the globe testifies to the weakness of webs of interconnection prior to 15,000 years ago. When people lived in small bands and rarely encountered other groups, they had limited opportunity to learn from and exchange with strangers. Over time, these groups grew apart. As we shall see, that trend eventually reversed itself as stronger webs multiplied the opportunities for exchanges.