Core Objectives

DESCRIBE the challenges that Afro-Eurasian empires and states faced in the first millennium BCE, and COMPARE the range of solutions they devised.

Core Objectives

DESCRIBE the challenges that Afro-Eurasian empires and states faced in the first millennium BCE, and COMPARE the range of solutions they devised.

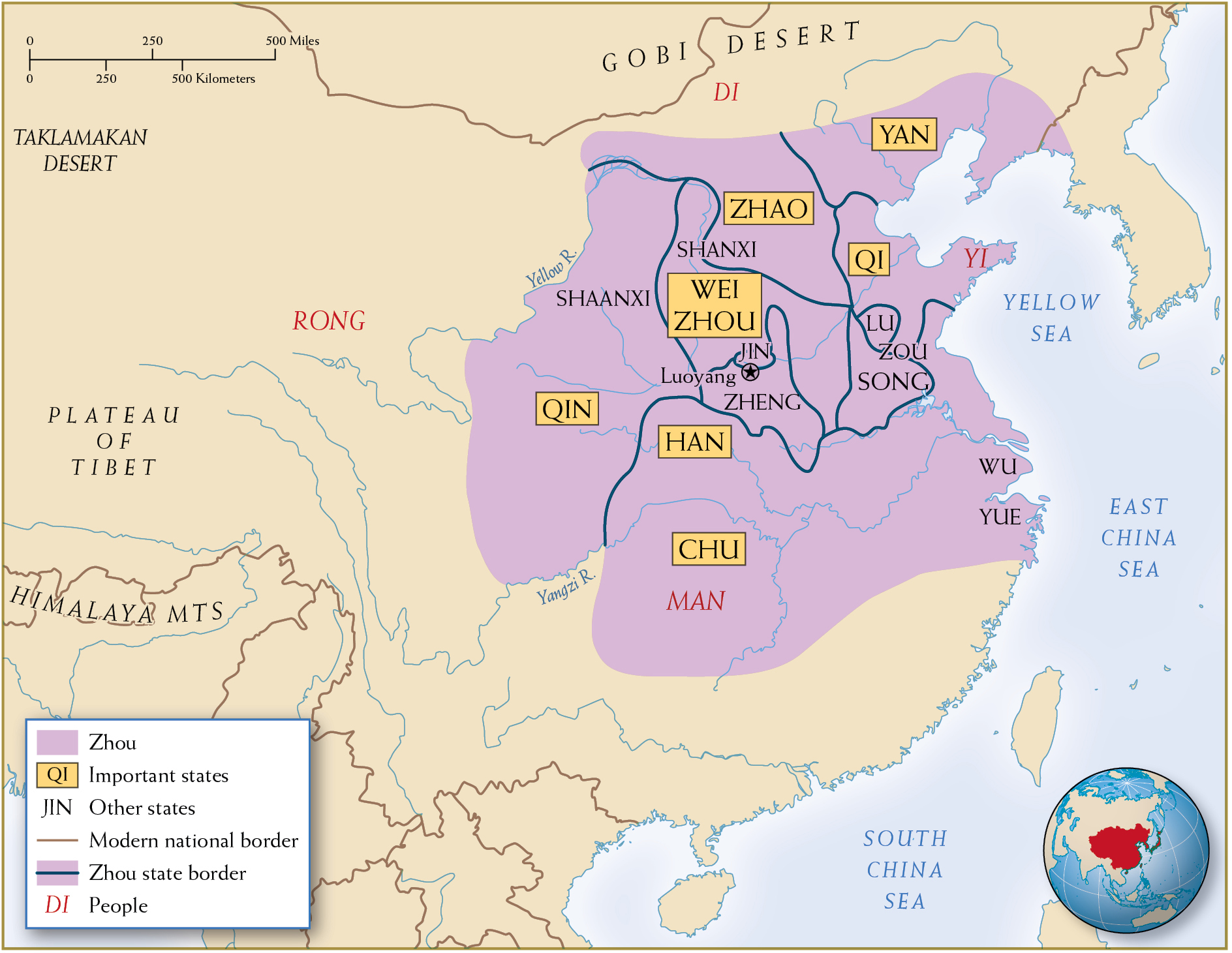

Destruction of the old political order paved the way for radical thinkers and cultural flourishing in Eastern Zhou China. Centered at Luoyang, the turbulent Eastern Zhou dynasty was divided by ancient Chinese chroniclers into the Spring and Autumn period (722–481 BCE) and the Warring States period (403–221 BCE). One writer from the Spring and Autumn period described over 500 battles among states and more than 100 civil wars within states, all taking place within 260 years. Fueling this warfare was the spread of cheaper and more lethal weaponry, made possible by new iron-smelting techniques, which in turn shifted influence from the central government to local authorities and allowed warfare to continue unabated into the Warring States period. Regional states became so powerful that they undertook large-scale projects, including dikes and irrigation systems, which had to this point been feasible only for empires. By the beginning of the Warring States period, seven large territorial states dominated the Zhou world. (See Map 5.2.) Their wars and shifting political alliances involved the mobilization of armies and resources on an unprecedented scale. Qin, the most powerful state, which ultimately replaced the Eastern Zhou dynasty in 221 BCE, fielded armies that combined huge infantries in the tens of thousands with lethal cavalries and skilled archers using state-of-the-art crossbows.

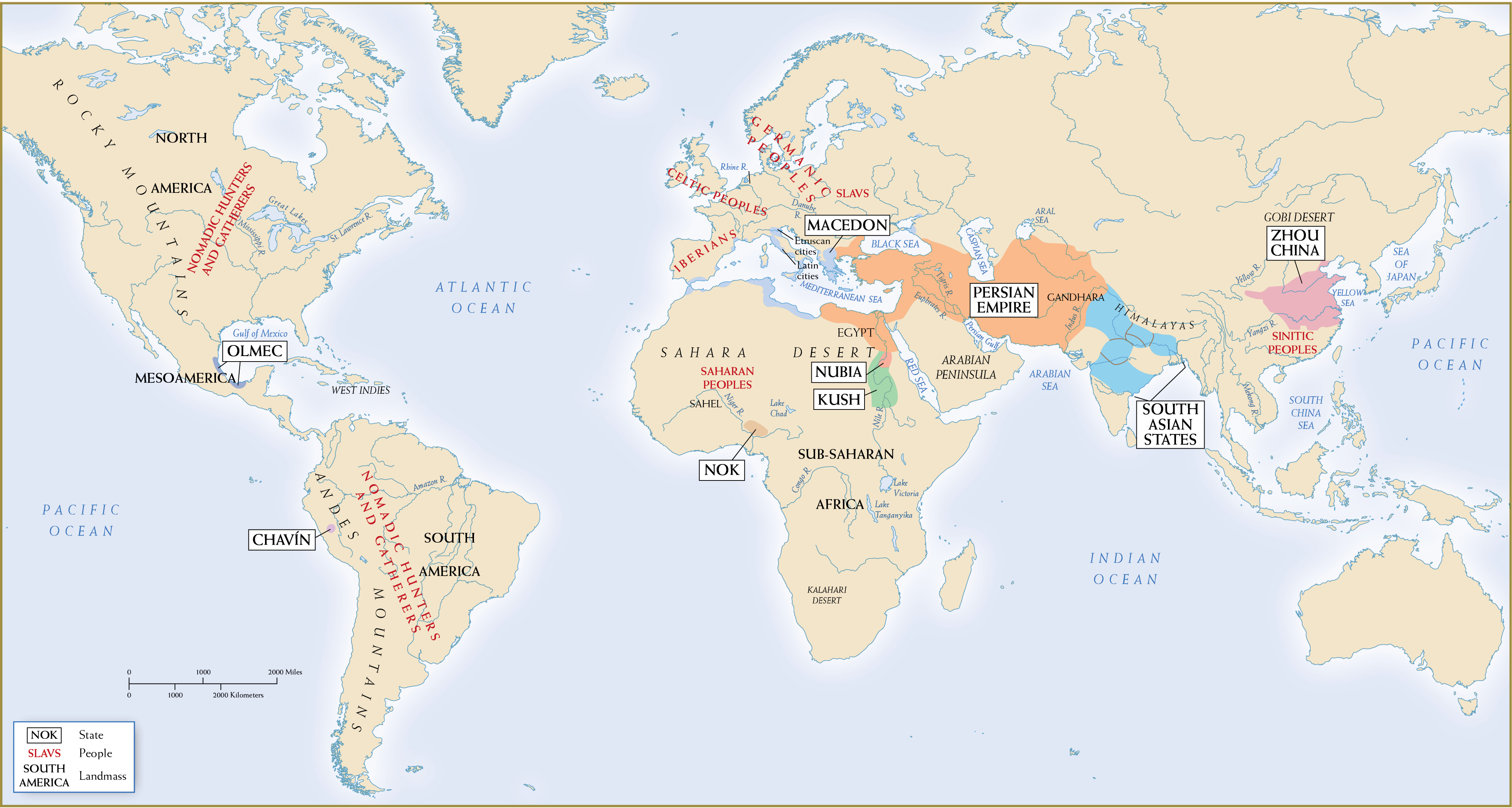

By the middle of the first millennium BCE, complex agriculture-based societies beyond the regional empires of Southwest Asia, North Africa, and East Asia contributed to the flowering of new cultural pathways and ideas that reshaped the old empires and territorial states into what we might call second-generation societies.

The Warring States period witnessed a fracturing of the Zhou dynasty into a myriad of states.

The conception of central power changed dramatically during this era. Royal appointees replaced hereditary officeholders. By the middle of the fourth century BCE, power was so concentrated in the major states’ rulers that each began to call himself “king” (wang). Despite—or perhaps even as a result of—the constant warfare, scholars, soldiers, merchants, peasants, and artisans thrived in the midst of an expanding agrarian economy and interregional trade.

Core Objectives

IDENTIFY Axial Age thinkers and ANALYZE their distinctive ideas.

Socrates and Confucius

Socrates and Confucius

Out of this turmoil came new visions that would shape Chinese thinking about the individual’s place in society and provide the philosophical underpinnings for the world’s most enduring imperial system (lasting from the establishment of the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE until the abdication of China’s last monarch in 1912). Often it was the losers among the political elites, seeking to replace their former advantages with new status gained through service, who sparked this intellectual creativity. Many important teachers emerged in China’s Axial Age, each with disciples. The philosophies of these “hundred masters,” a term mostly used at the time by itinerant scholars, constituted what came to be known as the Hundred Schools of Thought. Among the most influential were Confucianism and Daoism.

Confucius (551–479 BCE) was very much the product of the violent Spring and Autumn period. Serving in minor governmental positions, he believed the founders of the Zhou dynasty had established ideals of good government and principled action. Frustrated, however, by the realities of division and war among rival states all around him, Confucius set out in search of an enlightened ruler. Confucius’s teachings stemmed from his belief that human beings behaved ethically not because they wanted to achieve salvation or a heavenly reward but because it was in their human makeup to do so. Humanity’s natural tendencies, if left alone, produced harmonious existence. Confucius saw family and filial submission (the duty of children to parents) as the foundation of proper ethical action, including loyalty to the state and rulers. His idea of modeling the state on the patriarchal family—with the ruler respecting heaven as if it were his father and protecting his subjects as if they were his children—became a bedrock principle of Confucian thought. Although he regarded himself as a transmitter of ancient wisdom, Confucius established many of the major guidelines for Chinese thought and action: respect for the pronouncements of scholars, commitment to a broad education, and training for all who were highly intelligent and willing to work, whether noble or humble in birth. This equal access to training for those willing and able offered a dramatic departure from past centuries, when only nobles were believed capable of ruling. Nonetheless, Confucius’s distinctions between gentlemen-rulers and commoners continued to support a social hierarchy—although an individual’s position in that hierarchy now rested on education rather than on birth.

Confucius’s ethical teachings were preserved by his followers in a collection known as The Analects. These texts record Confucius’s conversations with his students. In his effort to persuade his contemporaries to reclaim what he regarded as the lost ideals of the early Zhou, Confucius proposed a moral framework stressing benevolence (ren), correct performance of ritual (li), loyalty to the family (xiao), and perfection of moral character to become a “superior man” (junzi)—that is, a man defined by benevolence and goodness rather than by the pursuit of profit. Confucius believed that a society of such superior men would not need coercive laws and punishment to achieve order. Confucius ultimately left court in 484 BCE, discouraged by the continuing state of warfare. His transformational ideology remained, however, and has shaped Chinese society for millennia, both through its followers and through those who adopted traditions that developed as a distinct counterpoint to Confucian engagement.

Another key philosophy was Daoism, which diverged sharply from Confucian thought by scorning rigid rituals and social hierarchies. Its ideas originated with a Master Lao (Laozi, “Old Master”), who—if he actually existed—may have been a contemporary of Confucius. His sayings were collected in The Daodejing, or The Book of the Way and Its Power (c. third century BCE). Master Lao’s book was then elaborated by Master Zhuang (Zhuangzi, c. 369–286 BCE). Master Lao is credited with saying, “The Sage, when he governs, empties [people’s] minds and fills their bellies. . . . His constant object is to keep the people without knowledge and without desire, or to prevent those who have knowledge from daring to act.” Daoism stressed that the best path (dao) for living was to follow the natural order of things. Its main principle was wuwei, “doing nothing.” Spontaneity, noninterference, and acceptance of the world as it is, rather than attempting to change it through politics and government, were what mattered. In Laozi’s vision, the ruler who interfered least in the natural processes of change was the most successful. Zhuangzi focused on the enlightened individual living spontaneously and in harmony with nature, free of society’s ethical rules and laws and viewing life and death simply as different stages of existence.

Xunzi and Han Fei Legalism, or Statism, another view of how best to create an orderly life, grew out of the writings of Master Xun (Xunzi, 310–237 BCE) toward the end of the Warring States period. He believed that men and women are innately bad and therefore require moral education and authoritarian control. In the decades before the Qin victory over the Zhou, the Legalist thinker Han Fei (280–233 BCE) agreed that human nature is primarily evil. He imagined a state with a ruler who followed the Daoist principle of wuwei, detaching himself from everyday governance—but only after setting an unbending standard (strict laws, accompanied by harsh punishments) for judging his officials and people. For Han Fei, the establishment and uniform application of these laws would keep people’s evil nature in check. As we will see in Chapter 7, the Qin state, before it became the dominant state in China, systematically followed the Legalist philosophy.

Apart from the philosophical discourse of the “hundred masters,” with its far-reaching impact across Chinese society, elites and commoners alike tried to maintain stability in their lives through religion, medicine, and statecraft. The elites’ rites of divination to predict the future and medical recipes to heal the body found parallels in the commoners’ use of ghost stories and astrological almanacs to understand the meaning of their lives and the significance of their deaths. Elites recorded their political discourses on wood and bamboo slips, tied together to form scrolls. They likewise prepared military treatises, ritual texts, geographic works, and poetry. The growing importance of statecraft and philosophical discourse promoted the use of writing, with 9,000 to 10,000 graphs or signs required to convey these elaborate ideas.

What emerged from all this activity was a foundational alliance between scholars and the state. Scholars became state functionaries who were dependent on rulers’ patronage. In return, rulers recognized scholars’ expertise in matters of punishment, ritual, astronomy, medicine, and divination. Philosophical deliberations focused on the need to maintain order and stability by preserving the state. These bonds that rulers forged with their scholarly elites were a distinguishing feature of governments in Warring States China, as compared with other Afro-Eurasian societies at this time.

Regional rulers of the Spring and Autumn period enhanced their ability to obtain natural resources, to recruit men for their armies, and to oversee conquered areas. This trend continued in the Warring States period, as the elites in the major states created administrative districts with stewards, sheriffs, and judges and a system of registering peasant households to facilitate tax collection and army conscription. These officials, who had been knights under the Western Zhou, were now bureaucrats in direct service to the ruler. These administrators were the “superior men” (junzi) of Confucian thought. They were paid in grain and sometimes received gifts of gold and silver, as well as titles and seals of office, from the ruler. The most successful of these ministers was the Qin statesman Shang Yang (fourth century BCE). Lord Shang’s reforms—including a head tax, administrative districts for closer bureaucratic control of hinterlands, land distribution for individual households to farm, and reward or punishment for military achievement—positioned the Qin to become the dominant state of its time.

With administrative reforms came reforms in military recruitment and warfare. In earlier periods, nobles had let fly their arrows from chariots while conscripted peasants fought beside them on the bloodstained ground. The Warring States, however, relied on massed infantries of peasants, whose conscription was made easier by the registration of peasant households. Bearing iron lances and unconstrained by their relationships with nobles, these peasants fought fiercely. In addition to this conscripted peasant infantry, armies boasted elite professional troops equipped with iron armor and weapons, and wielding the recently invented crossbow. The crossbow’s tremendous power, range, and accuracy enabled archers to kill lightly armored cavalrymen or charioteers at a distance. With improved siege technology, enemy armies assaulted the new defensive walls of towns and frontiers, either digging under them or using counterweighted siege ladders to scale them. Campaigns were no longer limited to an agricultural season and instead might stretch over a year or longer. The huge state armies contained as many as 1 million commoners in the infantry, supported by 1,000 chariots and 10,000 bow-wielding cavalrymen. During the Spring and Autumn period one state’s entire army would face another state’s, but by the Warring States period armies could divide into separate forces and wage several battles simultaneously.

While a growing population presented new challenges, the continuous warfare in these periods spurred economic growth in China. An agricultural revolution on the North China plain along the Yellow River led to rapid population growth, and the inhabitants of the Eastern Zhou reached approximately 20 million. Several factors contributed to increased agricultural productivity beginning in the Spring and Autumn period. Some rulers gave peasants the right to own their land in exchange for taxes and military service, which in turn increased productivity because the farmers were working to benefit themselves. Agricultural productivity was also enhanced by innovations such as crop rotation (millet and wheat in the north, rice and millet in the south) and oxen-pulled iron plowshares to prepare fields.

With this increased agricultural yield came the pressures of accompanying population growth. Ever-attentive peasant farmers tilling the fields of North and South China produced more rice and wheat than anyone else on earth, but that agricultural success was often outpaced by their growing families. As more people required more fuel, deforestation led to erosion of the fields. Many animals were hunted to extinction. Many inhabitants migrated south to domesticate the marshes, lakes, and rivers of the Yangzi River delta; here they created new arable frontiers out of former wetlands. When the expansion into arable land invariably hit its limits, Chinese families faced terrible food shortages and famines. The long-term economic result was a declining standard of living for massive numbers of Chinese peasants.

Despite these long-term cycles of population pressures and famine, larger harvests and advances in bronze and iron casting enabled the beginning of a market economy: trade in surplus grain, pottery, and ritual objects. Peasants continued to barter, but elites and rulers used minted coins. Grain and goods traveled along roads, rivers, and canals. Rulers and officials applied their military and organizational skills for public projects enhancing waterworks.

Economic growth had repercussions at all levels of society. Rulers attained a high level of cultural sophistication, as reflected in their magnificent palaces and burial sites. Archaeological evidence also suggests that commoners could purchase bronze metalwork, whereas previously only Zhou rulers and aristocrats could afford to do so. Social relations became more fluid as commoners gained power and aristocrats lost it. In Qin, for example, peasants who served in the ruler’s army could be rewarded with land, houses, enslaved servants, and even status change for killing enemy soldiers. While class relations had a revolutionary fluidity, gender relations became more rigid for elites and nonelites alike as male-centered kinship groups grew. The resulting separation of the sexes and male domination within the family affected women’s position. An emphasis on monogamy, or at least the primacy of the first wife over additional wives and concubines, emerged. Relations between the sexes became increasingly ritualized and constrained by moral and legal sanctions against any behavior that appeared to threaten the purity of authoritarian male lineages.

Even with the endless cycles of warfare and chaos—or perhaps because of them—many foundational beliefs, values, and philosophies for later dynasties sprang forth during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. By the middle of the first millennium BCE, China’s political activities and institutional and intellectual innovations affected larger numbers of people, over a much broader area, than did comparable developments in South Asia and the Mediterranean.