Core Objectives

COMPARE the role that religions and migration played in forging unified identities in Europe, India, and the Islamic worlds.

Core Objectives

COMPARE the role that religions and migration played in forging unified identities in Europe, India, and the Islamic worlds.

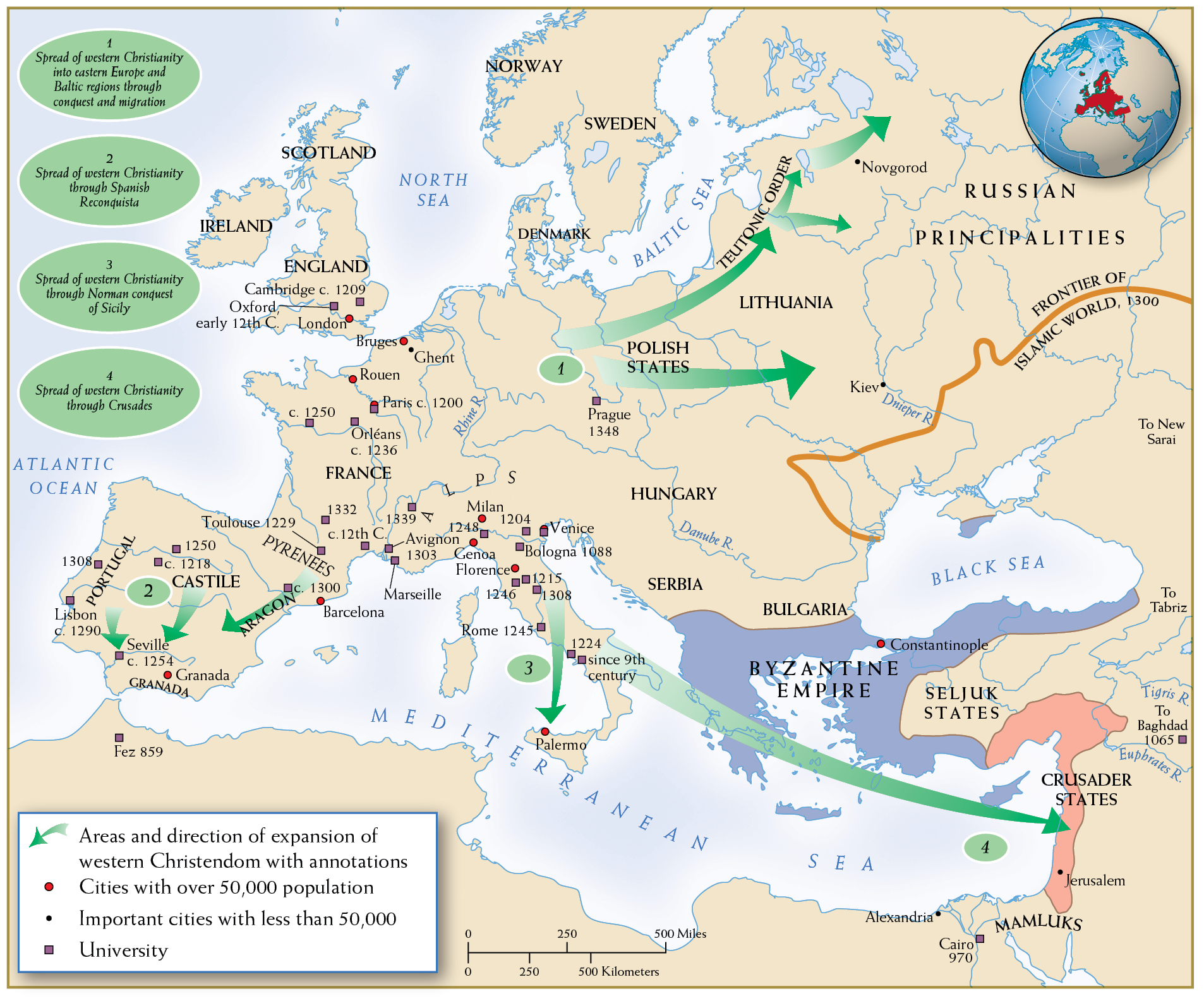

Europe, from 1000 to 1300 CE, was a region of strong contrasts. Intensely localized power was balanced by a shared sense of Europe’s place in the world, especially with respect to Christian identity. Some inhabitants even began to believe in the existence of something called “Europe” and increasingly referred to themselves as “Europeans” (see Map 10.7), especially in contrast to the world of Islam to the east and south.

The collapse of Charlemagne’s empire had exposed much of northern Europe to invasion, principally from the Vikings, and left the peasantry there with no central authority to protect them from local warlords. Armed with deadly weapons, these strongmen collected taxes, imposed forced labor, and became the unchallenged rulers of society. Peasants toiled under the authority of these landholding lords, who controlled every detail of their subjects’ lives. The Franks (in northern France) were the trendsetters for this development in eleventh- and twelfth-century Europe.

The peasantry’s subjugation to this knightly class was at the heart of a system scholars have called feudalism (emphasizing the power of the local lords over the peasantry), but a more accurate term for the system is manorialism, which emphasizes instead the manor’s role as the basic unit of economic power. The manor comprised the lord’s fortified home (or castle), the surrounding fields controlled by the lord but worked by peasants (as free tenants or as serfs tied to the land), and the village in which those peasants lived. Although manorialism was driven by agriculture, limited manufacturing and trade augmented the manor economy. This system harnessed agrarian energy and helped western Europe shed its identity as a somewhat “barbarian” appendage of the Mediterranean.

Catholic Europe expanded geographically and integrated culturally during this era.

Between 1100 and 1200, as many as 200,000 pioneering peasants emigrated from present-day Belgium, Holland, and northern Germany to the frontiers of Europe (now Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and the Baltic states). Despite its harsh climate and landscape, the area offered the promise of freedom from feudal lords’ arbitrary justice and the imposition of forced labor that the peasants had experienced in western Europe. In a fragile balance between the native elites and liberty-seeking newcomers, castles and villages echoing the landscape of manorial France now replaced local economies that had been based on gathering honey, hunting, and the slave trade. For a thousand miles along the Baltic Sea, forest clearings dotted with new farmsteads and small towns edged inward from the coast up the river valleys.

Russian lands modeled themselves after Byzantium, not Rome or western Europe. Set in a giant borderland between the steppes of Inner Eurasia and the booming centers of Europe, Russia’s cities lay at the crossroads of overland trade and migration. These cities were not agrarian centers, but hubs of expanding long-distance trade. Kiev became one of the region’s greatest urban centers, a small-scale Constantinople with its own miniature Hagia Sophia (see Chapter 8). Russian Christians looked not to the Roman Catholic faith associated with the popes in Rome, but rather to Byzantium’s Hagia Sophia and the Orthodoxy of the east as the source of religious authority. Russian Christianity remained that of a borderland—vivid oases of high culture set against the backdrop of vast forests and widely scattered settlements. Like the agricultural manors of western Europe, these Russian cities demonstrate the highly localized nature of power in Europe in this period.

Christianity in this era—primarily the Roman Catholicism of the west, but also the Orthodoxy of the east—became a universalizing faith that transformed the region becoming known as “Europe.” The Christianity of post-Roman Europe had been a religion of monks, and its most dynamic centers were great monasteries. Members of the laity were expected to revere and support their monks, nuns, and clergy, but not to imitate them. By 1200, all this had changed. The internal colonization of western Europe—the clearing of woods and founding of villages—ensured that parish churches arose in all but the wildest landscapes. Now the clergy reached more deeply into the private lives of the laity. Marriage and divorce, previously considered family matters, became the domain of the church.

New understandings of religious devotion and innovative institutions for learning developed in the west. For instance, the followers of Francis of Assisi (1182–1226) emerged as an order of preachers who brought a message of repentance. Franciscans encouraged the laity—from the poorest to the elite—to feel remorse for their wrongdoings, to confess their sins to local priests, and to strive to be better Christians. At nearly the same time, intellectuals were beginning to gather in Paris to form one of the first European universities, a sort of trade guild of scholars. These professional thinkers endeavored to prove that Christianity was the only religion that fully addressed the concerns of all rational human beings. Such was the message of Thomas Aquinas, who wrote Summa contra Gentiles (Summary of Christian Belief against Non-Christians) in 1264. The growing number of churches, new religious orders, and universities began to change what it meant to live in a “Christian Europe.”

In the late eleventh century, western Europeans launched the Crusades, a wave of attacks against the Muslim world. The First Crusade began in 1095, when Pope Urban II appealed to the warrior nobility of France to put their violence to good use: they should combine their role as pilgrims to Jerusalem with that of soldiers in order to free the Christian “holy land” from Muslim rule. Such a just war, the clergy proposed, was a means for absolution, not a source of sin.

Starting in 1097, an armed host of around 60,000 men set out from northwestern Europe to seize Jerusalem. The crusading forces included knights in heavy armor as well as people drawn from Europe’s impoverished masses, who joined the movement to help besiege cities and construct a network of castles as the Christian knights drove their frontier forward. The fleets of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa helped transport later Crusaders and supplied the kingdoms they created as they moved eastward. Later Crusaders, especially those from the upper class, brought their wives, who found a degree of autonomy away from their homeland. Eleanor of Aquitaine, for example, led her own army. Melisende (r. 1131–1152), born Armenian royalty in the Crusader state of Edessa, ruled as queen of Jerusalem after her father’s death, despite occasional attempts by her husband and later her son to challenge her authority. Regarded as wise and experienced in affairs of the state, she was popular with local Christians. As a result, the society of the Crusader states remained more open to women and the lower classes than in Europe. There are even accounts of a children’s crusade (1212), inspired by the visions of a boy. Over time, the Crusades drew together a range of peoples from varied walks of life in common purpose.

No fewer than nine Crusades were fought over the two centuries that followed Urban II’s call; but none of the coalitions, in the end, created lasting Christian kingdoms in the lands the Crusaders “reconquered.” Most knights returned home, their epic pilgrimages completed. The remaining fragile network of Crusader lordships barely threatened the Islamic heartland. The real prosperity and the capital cities of Muslim kingdoms lay inland, away from the coast—at Cairo, Damascus, and Baghdad. The assaults’ long-term effect was to harden Muslim feelings against the Franks and the millions of nonwestern Christians who had previously lived peacefully in Egypt and Syria.

Even so, a range of sources offer Muslim and Christian perspectives that show tolerance of, and curiosity about, each other. For example, Usāmah Ibn Munqidh (1095–1188), a learned Syrian leader, describes his shock at the Frankish Crusaders’ backward medical practices and the freedom they offered their wives, in addition to well-meaning exchanges such as a particular Frank’s confusion about the direction in which Muslims pray. Similarly, Jean de Joinville (1224–1317), a French chronicler of Louis X of France who led the Seventh Crusade, marveled at the order within the sultan’s camp and the role of musicians in calling the Muslim forces to hear the sultan’s orders.

Other campaigns of Christian expansion, like the Iberian efforts to drive out the Muslims, were more successful. Beginning with the capture of Toledo in 1061, the Christian kings of northern Spain slowly pushed back the Muslims. Eventually they reached the heart of Andalusia in southern Iberia and conquered Seville, adding more than 100,000 square miles of territory to Christian Europe. Another force, from northern France, crossed Italy to conquer Muslim-held Sicily, ensuring Christian rule in that strategically located mid-Mediterranean island. Unlike the Crusaders’ fragile foothold at the edge of the Middle East, these two conquests were a turning point in relations between Christian and Muslim power in the Mediterranean. Christianity—and in particular the rise of the Roman Catholic Church, the spread of universities, and the fight against the Muslims in their native and spiritual homelands—was a force that helped create a cultural sphere known as Europe, whose peoples would become known as European, at the western end of the Afro-Eurasian landmass during this period.