Core Objectives

COMPARE the internal integration and external interactions of sub-Saharan Africa with those of the Americas, and with the connected Eurasian world.

Core Objectives

COMPARE the internal integration and external interactions of sub-Saharan Africa with those of the Americas, and with the connected Eurasian world.

From 1000 to 1300 CE, sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas became far more internally integrated—culturally, economically, and politically—than before. Islam’s spread and the growing trade in gold, enslaved people, and other commodities brought sub-Saharan Africa more fully into the exchange networks of the Eastern Hemisphere, but the Americas remained isolated from Afro-Eurasian networks for several more centuries.

A Connected World

A Connected World

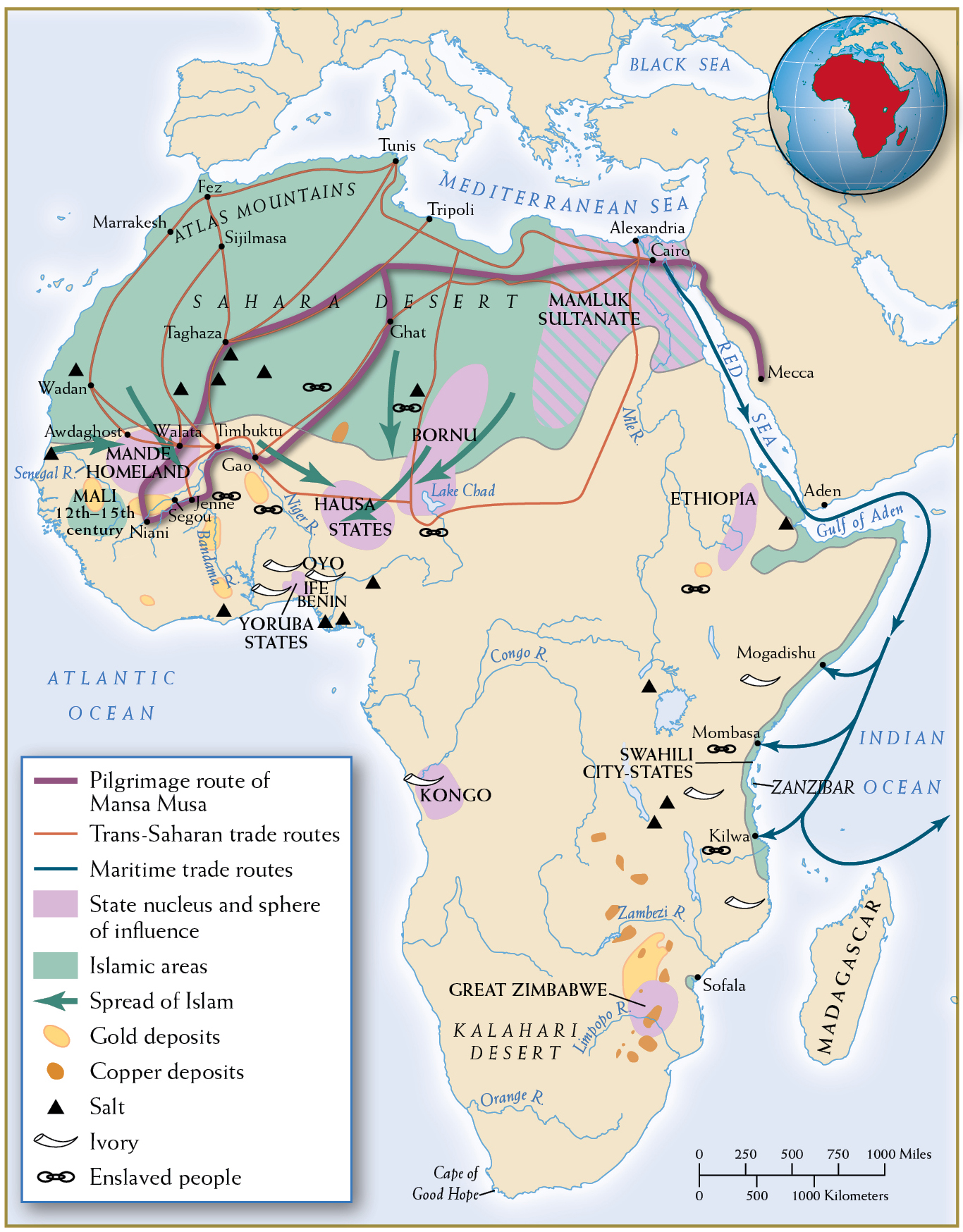

During this period, sub-Saharan Africa’s relationship to the rest of the world changed dramatically. While sub-Saharan Africa had never been a world entirely apart before 1000 CE, its integration with Eurasia now became much stronger. Increasingly, its hinterlands found themselves touched by the commercial and migratory impulses emanating from the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea transformations. (See Map 10.8.)

West Africa and the Mande-Speaking Peoples Once trade routes bridged the Sahara Desert (see Chapter 9), the flow of commodities and ideas linked sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa and Southwest Asia. As the savanna region became increasingly connected to developments in Eurasia, Mande-speaking peoples became the primary agents for integration within and beyond West Africa. Exploiting their expertise in commerce and political organization, the Mande edged out rivals. The Mande homeland was a vast area, 1,000 miles wide, between the bend in the Senegal River to the west and the bend of the Niger River to the east, and stretching more than 2,000 miles from the Senegal River in the north to the Bandama River in the south.

Increased commercial contacts influenced the religious and political dimensions of sub-Saharan Africa at this time. Compare this map with Map 9.3.

By the eleventh century, the Mande-speaking peoples were spreading their cultural, commercial, and political hegemony from the savanna grasslands southward into the woodlands and tropical rain forests stretching to the Atlantic Ocean. Those dwelling in the rain forests organized small-scale societies led by local councils, while those in the savanna lands developed centralized forms of government under sacred kingships. Mande speakers believed that their kings had descended from the gods and that they enjoyed the gods’ blessing.

As the Mande extended their territory to the Atlantic coast, they gained access to tradable items that residents of Africa’s interior were eager to have—notably kola nuts and malaguetta peppers, for which the Mande exchanged iron products and manufactured textiles. Mande-speaking peoples, with their far-flung commercial networks and highly dispersed populations, dominated trans-Saharan trade in salt from the northern Sahel, gold from the Mande homeland, and enslaved people. By 1300, Mande-speaking merchants had followed the Senegal River to its outlet on the Atlantic coast and then pushed their commercial frontiers farther inland and down the coast. Thus, even before European explorers and traders arrived in the mid-fifteenth century, West African peoples had created dynamic networks linking the hinterlands with coastal trading hubs.

The Mali Empire In the early thirteenth century, the Mali Empire became the Mande successor state to the kingdom of Ghana (see Chapter 9). The origins of the Mali Empire and its legendary founder are enshrined in The Epic of Sundiata. Sundiata’s triumph, which occurred in the first half of the thirteenth century, marked the victory of new cavalry forces over traditional foot soldiers. Horses now became prestige objects for the savanna peoples, symbols of state power.

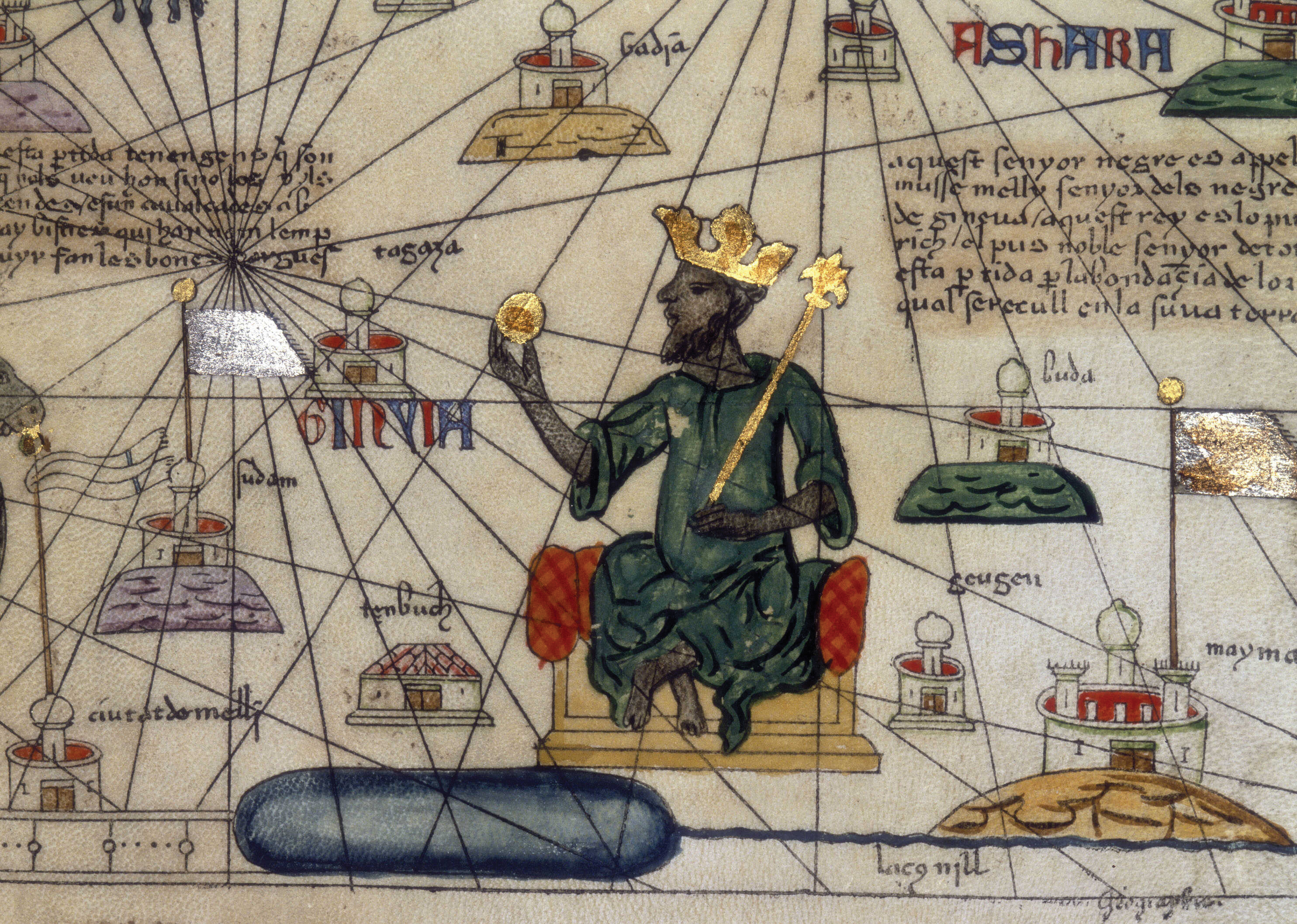

Mansa Musa’s Hajj

Mansa Musa’s Hajj

Under the Mali Empire, commerce was in full swing. With Mande trade routes extending to the Atlantic Ocean and spanning the Sahara Desert, West Africa was no longer an isolated periphery of the central Muslim lands. Mansa Musa (r. 1312–1332), perhaps Mali’s most famous sovereign, made a celebrated hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca, in 1324–1325. He traveled through Cairo and impressed crowds with the size of his retinue—including soldiers, wives, consorts, and as many as 12,000 enslaved people—and his displays of wealth, especially many dazzling items made of gold. Mansa Musa’s lengthy three-month stopover in Cairo, one of Islam’s primary cities, astonished the Egyptian elite and awakened much of the world to the fact that Islam had spread far below the Sahara and that a sub-Saharan state could mount such an impressive display of power and wealth.

The Mali Empire boasted two of West Africa’s largest cities. Jenne, an entrepôt dating back to 200 BCE, was a vital assembly point for caravans laden with salt, gold, and enslaved people preparing for journeys west to the Atlantic coast and north over the Sahara. More spectacular was the city of Timbuktu; founded around 1100 as a seasonal camp for nomads, it grew in size and importance under the patronage of various Mali kings. By the fourteenth century, it was a thriving commercial, intellectual, and religious center famed for its three large mosques, which are still standing.

Trade between East Africa and the Indian Ocean Africa’s eastern and southern regions were also integrated into long-distance trading systems. Because of the monsoon winds, East Africa was a logical end point for much of the Indian Ocean trade. Swahili peoples living along that coast became brokers for trade from the Arabian Peninsula, the Persian Gulf territories, and the western coast of India. Merchants in the city of Kilwa on the coast of present-day Tanzania brought ivory, gold, enslaved people, and other items from the interior and shipped them to destinations around the Indian Ocean.

Shona-speaking peoples grew rich by mining the gold ore in the highlands between the Limpopo and Zambezi Rivers. By 1000 CE, the Shona had founded up to fifty small religious and political centers, each one erected from stone to display its power over the peasant villages surrounding it. Around 1100, one of these centers, Great Zimbabwe, stood supreme among the Shona. Built on the fortunes made from gold, its most impressive landmark was a massive elliptical building made of stones fitted so expertly that they needed no grouting.

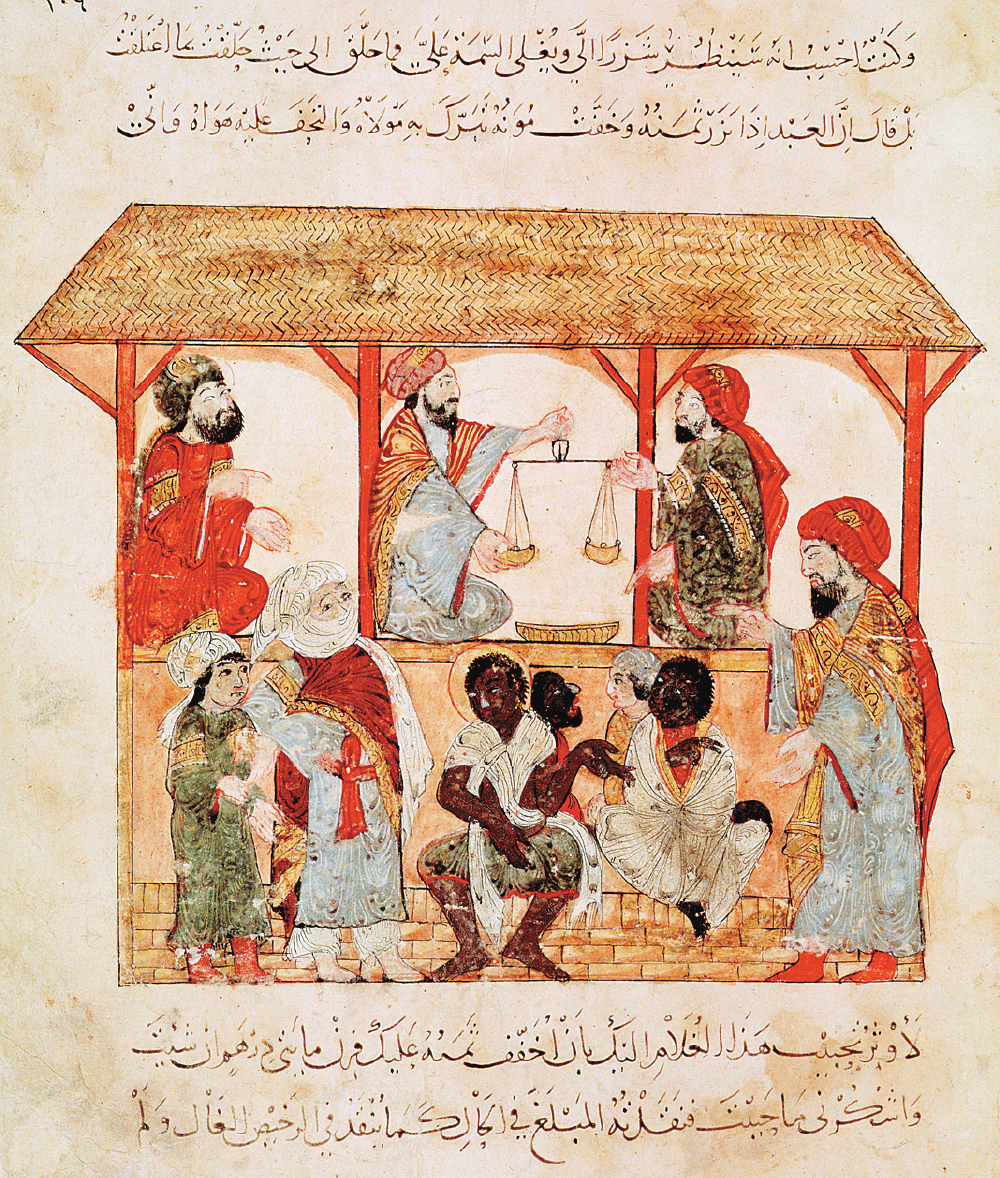

Enslaved African people were as valuable as African gold in shipments to Indian Ocean as well as Mediterranean markets. After Islam spread into Africa and sailing techniques improved, the slave trade across the Sahara Desert and Indian Ocean boomed. Although the Quran mitigated the severity of slavery by requiring Muslim enslavers to treat their workers kindly and praising those who freed the enslaved, the African slave trade flourished under Islam. Africans became enslaved either by being taken as prisoners of war or by being sold into slavery as punishment for committing a crime. Enslaved people might work as soldiers, seafarers on dhows, domestic servants, or plantation workers. Conditions for plantation laborers on the agricultural estates of lower Iraq were so oppressive that they led, in the ninth century CE, to one of the most significant slave wars documented in world history (the Zanj rebellion). Yet in this era, plantation slave labor, like that which later became prominent in the Americas in the nineteenth century, was the exception, not the rule.

During this period, the Americas were untouched by the connections reverberating across Afro-Eurasia. Apart from limited Viking contacts in North America (see Chapter 9), navigators still did not cross the large oceans that separated the Americas from other lands. Yet, here, too, commercial and expansionist impulses fostered closer contact among peoples who lived there.

Andean States of South America Growth and prosperity in the Andean region gave rise to South America’s first empire. The Chimú Empire developed early in the second millennium in the fertile Moche Valley bordering the Pacific Ocean. (See Map 10.9.) Ultimately, the Moche people expanded their influence across numerous valleys and ecological zones, from pastoral highlands to rich valley floodplains to the fecund fishing grounds of the Pacific coast. As their geographic reach grew, so did their wealth.

The Chimú economy was successful because it was highly commercialized. Agriculture was its base, and complex irrigation systems turned the arid coast into a string of fertile oases capable of feeding an increasingly dispersed population. Cotton became a lucrative export to distant markets along the Andes. Parades of llamas and porters lugged these commodities up and down the steep mountain chains that form the spine of South America. A well-trained bureaucracy oversaw the construction and maintenance of canals, and a hierarchy of provincial administrators watched over commercial hinterlands.

The Chimú Empire’s biggest city was Chan Chan, which had been growing ever larger since its founding around 900 CE. By the time the Chimú Empire was thriving, Chan Chan held a core population of 30,000 inhabitants. A sprawling walled metropolis covering nearly 10 square miles, with extensive roads circulating through its neighborhoods, Chan Chan boasted ten huge palaces at its center. Protected by thick walls 30 feet high, these opulent residence halls symbolized the rulers’ power. Within the compound, emperors erected burial complexes for storing their accumulated riches: fine cloth, gold and silver objects, splendid Spondylus shells, and other luxury goods. Around the compound spread neighborhoods for nobles and artisans; farther out stood rows of commoners’ houses. The Chimú regime, centered at Chan Chan, lasted until Inca armies invaded in the 1460s and incorporated the Pacific state into their own immense empire.

Although the Andes region of South America was isolated from Afro-Eurasian developments before 1500, it was not stagnant. Indeed, political and cultural integration brought the peoples of this region closer together.

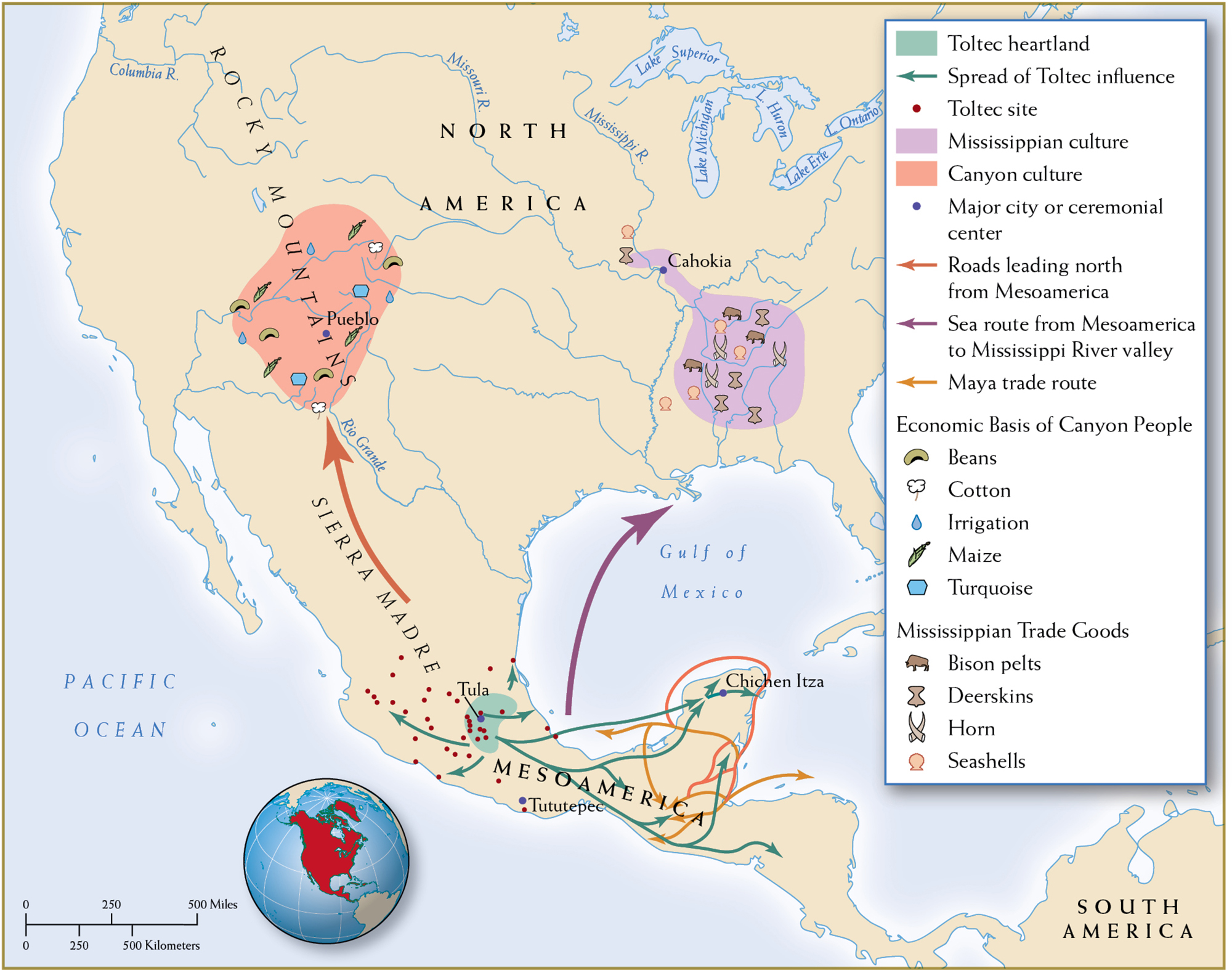

Toltecs in Mesoamerica Additional hubs of regional trade developed farther north. By 1000 CE, Mesoamerica had seen the rise and fall of several complex societies, including Teotihuacán and the Maya (see Chapter 8). Caravans of porters bound the region together, working the intricate roads that connected the coast of the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific and the southern lowlands of Central America to the arid regions of modern Texas. (See Map 10.10.) The Toltecs filled the political vacuum left by the decline of Teotihuacán and tapped into the commercial network radiating from the rich valley of central Mexico.

The Toltecs grew to dominate the valley of Mexico between 900 and 1100 CE. They were a combination of migrant groups, farmers from the north and refugees from the south fleeing the strife that followed Teotihuacán’s demise. These migrants settled northwest of Teotihuacán as the city waned, making their capital at Tula. They relied on a maize-based economy supplemented by beans, squash, and dog, deer, and rabbit meat. Their rulers made sure that enterprising merchants provided them with status goods such as ornamental pottery, rare shells and stones, and precious skins and feathers.

Tula was a commercial hub, a political capital, and a ceremonial center. While its layout differed from Teotihuacán’s, many features revealed borrowings from other Mesoamerican peoples. Temples consisted of giant pyramids topped by colossal stone soldiers, and ball courts where subjects and conquered peoples alike played their ritual sport were found everywhere. The architecture and monumental art reflected the mixed and migratory origins of the Toltecs in a combination of Maya and Teotihuacáno influences. At its height, the Toltec capital teemed with 60,000 people, a huge metropolis by contemporary European standards (if small by Song Chinese and Abbasid standards).

Both Cahokia and Tula were commercial hubs of vibrant regional trade networks.

Cahokians in North America As in South America and Mesoamerica, cities took shape at the hubs of trading networks across North America. The largest was Cahokia, along the Mississippi River near modern-day East St. Louis, Illinois. A city of about 15,000, it approximated the size of London at the time. Farmers and hunters had settled in the region around 600 CE, attracted by its rich soil, its woodlands that provided fuel and game, and its access to trade via the Mississippi. Eventually, fields of maize and other crops fanned out toward the horizon. The hoe replaced the trusty digging stick, and satellite towns erected granaries to hold the growing harvests.

By 1000 CE, Cahokia was an established commercial center for regional and long-distance trade. The hinterlands produced staples for Cahokia’s urban consumers, and in return its crafts rode inland on the backs of porters and to distant markets in canoes. Woven fabrics and ceramics from Cahokia were exchanged for mica from the Appalachian Mountains, seashells and sharks’ teeth from the Gulf of Mexico, and copper from the upper Great Lakes. Cahokia became more than an importer and exporter: it was the exchange hub for an entire regional network trading in salt, tools, pottery, woven stuffs, jewelry, and ceremonial goods.

Dominating Cahokia’s urban landscape were enormous earthen mounds of sand and clay (thus the Cahokians’ nickname of “mound people”). It was from these artificial hills that the people honored spiritual forces. Building these types of structures without draft animals, hydraulic tools, or even wheels was labor-intensive, so the Cahokians recruited neighboring people to help. A palisade around the city protected the metropolis from marauders.

Ultimately, Cahokia’s success bred its downfall. As woodlands fell to the axe and the soil lost its nutrients, timber and food became scarce. In contrast to the sturdy dhows of the Arabian Sea and the bulky junks of the China seas, Cahokia’s river canoes could carry only limited cargoes. Cahokia’s commercial networks met their limits. When the creeks that fed its water system could not keep up with demand, engineers changed their course, but to no avail. By 1350 the city was practically empty. But Cahokia represented the growing networks of trade and migration in North America and the ability of North Americans to organize vibrant commercial societies.

Two forces contributed to greater integration in sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas from 1000 to 1300 CE: commercial exchange (of salt, gold, ivory, and enslaved people in sub-Saharan Africa and shells, pottery, textiles, and metals in the Americas) and urbanization (at Jenne, Timbuktu, and Great Zimbabwe in sub-Saharan Africa and at Chan Chan, Tula, and Cahokia in the Americas). By 1300, trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean exchange had brought Africa into full-fledged Afro-Eurasian networks of exchange and, as we will see in Chapter 12, transatlantic exchange would soon bring the Americas into a global network.