Core Objectives

COMPARE the ways in which regional rulers in post-plague Afro-Eurasia attempted to construct unified states, and ANALYZE the extent and nature of their successes.

Core Objectives

COMPARE the ways in which regional rulers in post-plague Afro-Eurasia attempted to construct unified states, and ANALYZE the extent and nature of their successes.

The devastation of the Black Death followed hard on the heels of the Mongol destruction of Islam’s most important city, Baghdad, and Islam’s old political order. The double shock of conquest and disease shattered whatever was left of Islamic unity and cleared the way for new Islamic states to emerge. The old, Arabic-speaking Islamic world remained vital in Islam’s geographic heartland, but it now had to yield authority to new rulers and religious men. This new Islamic world included large Turkish- and Persian-speaking populations as well. The implosion of the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad made way for powerful, more militarized, expansionist successors capable of extending Islam’s reach into Christian heartlands in the west and the Delhi Sultanate in the east.

The recovery from conquest and disease was slow. Eventually, the Ottomans, the Safavids, and the Mughals emerged as the dominant states in the Islamic world in the early sixteenth century. They exploited the rich agrarian resources of the Indian Ocean regions and the Mediterranean basin, and they benefited from a brisk seaborne and overland trade. By the mid-sixteenth century the Mughals controlled the northern Indus River valley; the Safavids occupied Persia; and the Ottomans ruled Anatolia, the Arab world, and much of southern and eastern Europe. Here we will explore in depth the Ottoman Empire, which emerged first and endured the longest of the three. (See Chapter 12 for a fuller discussion of the Mughals and Chapter 14 for more on the Safavids.)

The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire

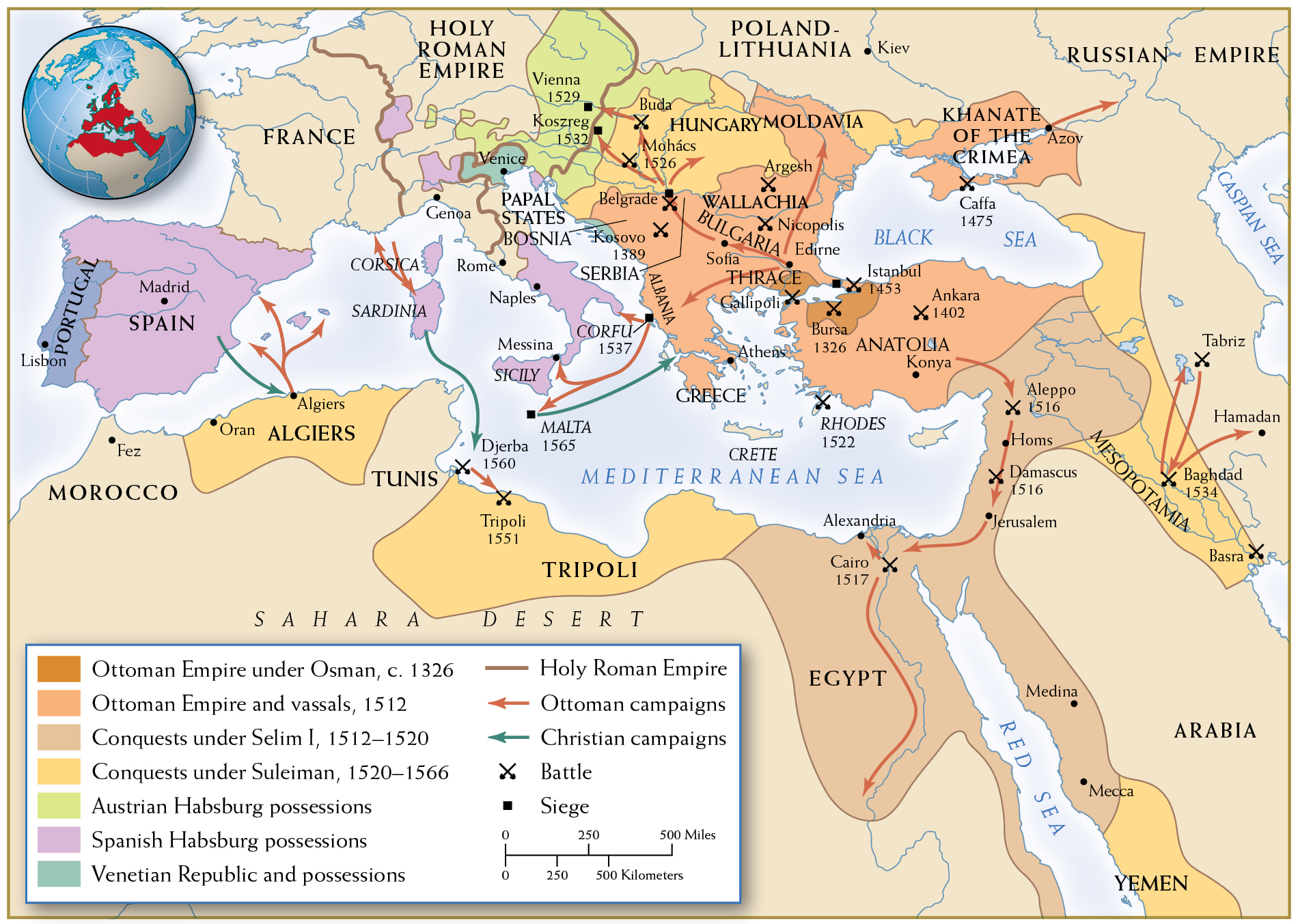

The rise of the Ottoman Empire owed as much to innovative administrative techniques and religious tolerance as to military strength. Although the Mongols considered Anatolia to be a borderland region of little economic importance, their military forays in the late thirteenth century opened up the region to new political forces. The ultimate victors here were the Ottoman Turks. They transformed themselves from warrior bands roaming the borderlands between the Islamic and Christian worlds into rulers of a settled state and, finally, into sovereigns of a far-flung, highly bureaucratic empire. (See Map 11.2.)

Under their chief, Osman (r. 1299–1326), the Turkish Ottomans formalized a stern and disciplined warrior ethos. In addition to deploying their fierce warriors, knowns as ghazis, Osman and his son Orhan (r. 1326–1362), both Sunni Muslims, proved skilled at working with those who held different religious beliefs, including Byzantine Christians, Sufi dervishes, and Shiites. Osman and Orhan offered genuine opportunities for others to exercise power and gain wealth. While other Turkish warrior bands fought for booty under charismatic military leaders, they failed because, unlike the Ottomans, they did not integrate these religious groups and the range of artisans, merchants, bureaucrats, and clerics whose support was essential in the Ottoman rise to power. The Ottomans triumphed over their rivals by adapting techniques of administration from neighboring groups and by attracting those groups to their rule. In time, not only did the Ottoman state win the favor of Islamic clerics, but it also became the champion of Sunni Islam throughout the Islamic world.

This map charts the expansion of the Ottoman state from the time of its founder, Osman, through the reign of Suleiman, the empire’s most illustrious ruler.

By the mid-fourteenth century, the Ottomans had expanded into the Balkans, becoming the most powerful force in the eastern Mediterranean and western Asia. By the early sixteenth century, the Ottoman state controlled a vast territory, stretching in the west to the Moroccan border, in the north to Hungary and Moldavia, in the south through the Arabian Peninsula, and in the east to the Persian border. What was impressive and new within the Islamic world was the Ottomans’ elaborate administrative hierarchy, atop which stood the sultan. Below him was a military and civilian bureaucracy whose task was to demand obedience and revenue from subjects. The bureaucracy’s discipline enabled the sultan to expand his realm, which in turn forced him to invest in an even larger bureaucracy.

The empire’s spectacular expansion was primarily a military affair. To recruit followers, the Ottomans promised wealth and glory to new subjects. This was an expensive undertaking, but territorial expansion generated vast financial and administrative rewards. Moreover, by spreading the spoils of conquest and lucrative administrative positions, rulers bought off potentially unhappy subordinates. Still, without military might, the Ottomans would not have enjoyed the successes associated with the brilliant reigns of Murad II (r. 1421–1451) and his appropriately named successor, Mehmed the Conqueror (r. 1451–1481).

Mehmed’s most spectacular triumph was the conquest of Constantinople, an ambition for Muslim rulers ever since the birth of Islam. Mehmed left no doubt that this was his primary goal: shortly after his coronation, he vowed to capture Constantinople, the ancient Roman and Christian capital of the Byzantine Empire, and a city of immense strategic and commercial importance, which had withstood Muslim efforts at conquest for centuries. First, Mehmed built a fortress of his own to prevent European vessels from reaching the capital. Then, by promising his soldiers free access to booty and portraying the city’s conquest as a holy cause, he amassed a huge army that outnumbered the defending force of 7,000 by more than ten times. For fifty-three days his troops bombarded Constantinople’s massive walls with artillery that included enormous cannons built by Hungarian and Italian engineers. On May 29, 1453, Ottoman troops overwhelmed the surviving defenders and took Constantinople—which Mehmed promptly renamed Istanbul.

The Tools of Empire Building The Ottomans adopted Byzantine administrative practices to unify their enlarged state and incorporated many of Byzantium’s powerful families into it. Their dynastic power, however, was not only military; it also rested on a firm religious foundation. At the center of this empire was the sultan, who combined a warrior ethos with an unwavering devotion to Islam. Describing himself as the “shadow of God” on earth, the sultan claimed the role of caretaker for the Islamic faith. Throughout the empire, he devoted substantial resources to the construction of elaborate mosques and to the support of Islamic schools. As self-appointed defender of the faith, the sultan assumed the role of protector of the holy cities on the Arabian Peninsula and of Jerusalem, while working to unite the realm’s diverse lands and peoples and constantly striving to extend the borders of Islam. During the reign of Suleiman (r. 1520–1566), the Ottomans reached the height of their territorial expansion. Under his administration, the Ottoman state ruled 20 to 30 million people. By the time Suleiman died, the Ottoman Empire bridged Europe and the Arab world.

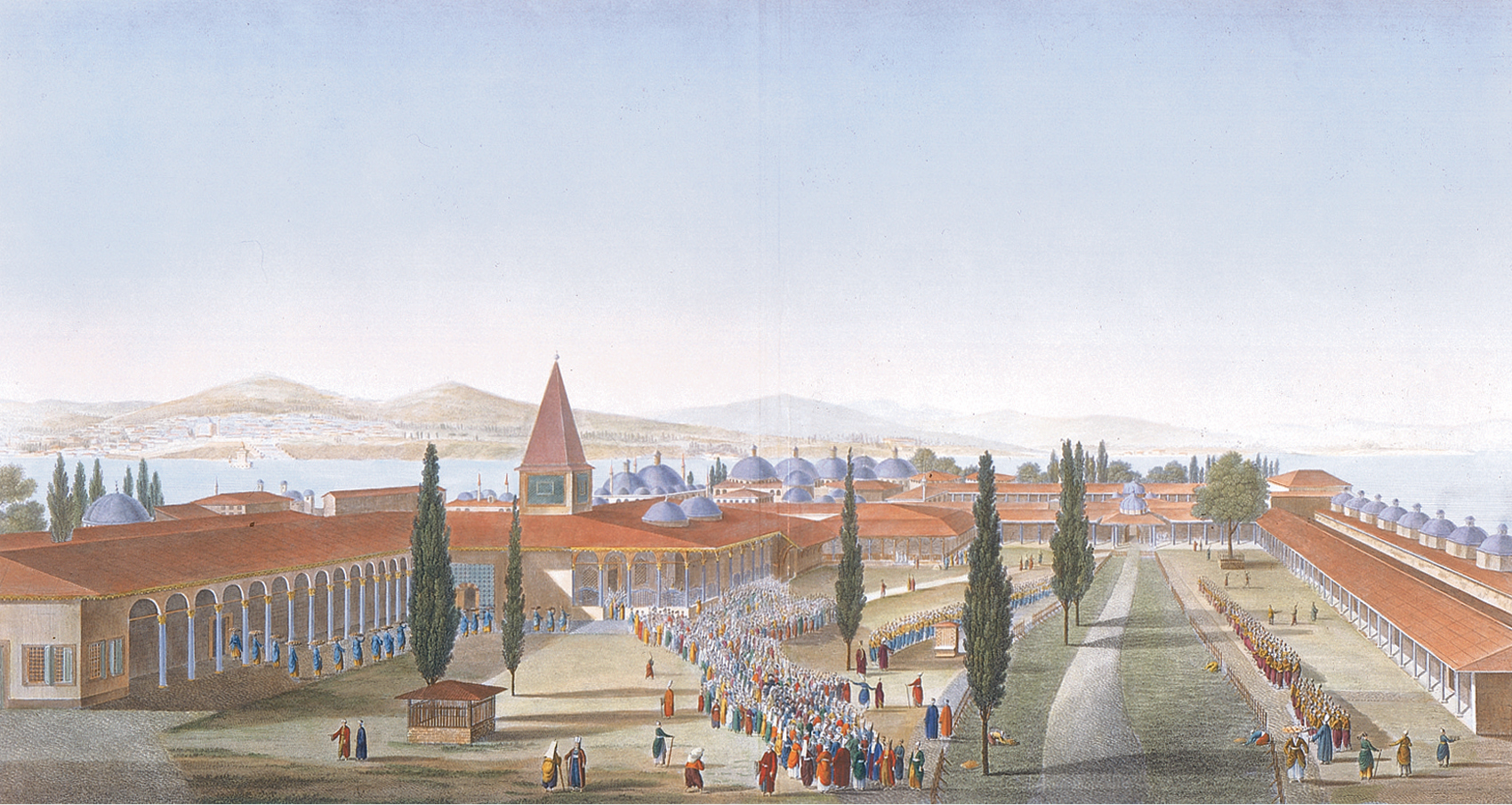

Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace exhibited the Ottomans’ view of governance, the sultans’ emphasis on religion, and the continuing influence of Ottoman familial traditions. Laid out by Mehmed II, the palace complex projected a vision of Istanbul as the center of the world. As a way to promote the sultan’s magnificent power, architects designed the complex so that the buildings containing the imperial household were nestled behind layers of outer courtyards, in a mosaic of mosques, courts, and special dwellings for the sultan’s harem. The harem had its own hierarchy of thousands of women, from the sultan’s mother and consorts to the enslaved women who waited on them, and it became a formidable political force at the heart of Ottoman power.

The growing importance of Topkapi Palace as the command post of empire represented a crucial transition in the history of Ottoman rulers. Not only was the palace the place where future bureaucrats received their training; it was also the place where the chief bureaucrat, the grand vizier, carried out the day-to-day running of the empire. Whereas the early sultans had led their soldiers into battle personally and had met face-to-face with their kinsmen, the later rulers withdrew into the sacredness of the palace, venturing out only occasionally for grand ceremonies. Still, every Friday, subjects lined up outside the palace to introduce their petitions, ask for favors, and seek justice. If they were lucky, the sultans would be there to greet them—but they did so behind grated glass, issuing their decisions by tapping on the window. The palace thus projected a sense of majestic, distant wonder, a home fit for semidivine rulers.

Diversity and Control The Ottoman Empire’s endurance into the twentieth century owed much to the ruling elite’s ability to gain the support and employ the talents of exceedingly diverse populations. After all, neither conquest nor conversion eliminated cultural differences among the empire’s distant provinces. Thus, for example, the Ottomans’ language policy was one of flexibility and tolerance. Although Ottoman Turkish was the official language of administration, Arabic was the primary language of the Arab provinces, the common tongue of street life. Within the empire’s European lands, many people spoke their own languages. From the fifteenth century onward, the Ottoman Empire was perhaps more multilingual than any of its rivals.

In politics, as in language, the Ottomans showed flexibility and tolerance. The imperial bureaucracy permitted extensive regional autonomy. In fact, Ottoman military cadres perfected a technique for absorbing newly conquered territories into the empire by parceling them out as revenue-producing units among loyal followers and kin. Regional appointees could collect local taxes, part of which they earmarked for Istanbul and part of which they pocketed for themselves. This approach was a common administrative device for many world dynastic empires ruling extensive domains.

Like other empires, the Ottoman state was always in danger of losing control over its provincial rulers. Local potentates—the group that the imperial center allowed to rule in their distant regions—found that great distances enabled them to operate independently from central authority. These rulers kept larger amounts of tax revenues than Istanbul deemed proper. So, to limit their autonomy, the Ottomans established the janissaries, a corps of infantry soldiers and bureaucrats who owed direct allegiance to the sultan. The system at its high point involved conscription of Christian youths from the empire’s European lands. This conscription, called the devshirme, required each village to hand over a certain number of males between the ages of eight and eighteen. Uprooted from their families and villages, these young men—selected for their fine physiques and good looks—were converted to Islam and sent to farms to build up their bodies and learn Turkish. A select few were moved on to Topkapi Palace to learn Ottoman military, religious, and administrative techniques. Some of these men—such as the architect Sinan, who designed the Süleymaniye Mosque—later enjoyed exceptional careers in the arts and sciences. Recipients of the best education available in the Islamic world, trained in Ottoman ways, instructed in the use of modern weaponry, and deprived of family connections, the devshirme recruits were prepared to serve the sultan (and the empire as a whole) rather than the interests of any particular locality or ethnic group.

Thus, the Ottomans established their legitimacy via military skill, religious backing, and a loyal bureaucracy. They artfully balanced the decentralizing tendencies of the outlying regions with the centralizing forces of the imperial capital. Relying on a careful mixture of religious faith, imperial patronage, and cultural tolerance, the sultans curried loyalty and secured political stability. Indeed, the Ottoman Empire was so strong and stable that it dominated the coveted and highly contested trading crossroads between Europe and Asia for many centuries. Thus, its consolidation had powerful consequences for Europeans’ efforts to rebuild their societies after the plague; above all, it closed off their traditional overland trade routes to India and China.