The Big Picture

How would you describe the broad patterns of world trade after 1450?

The Big Picture

How would you describe the broad patterns of world trade after 1450?

Ottoman expansion overland pushed Europeans to probe westwards overseas. Both Ottoman and European expansion caused important global shifts in the organization of polities as well as in patterns of trade. The two were interconnected, as increasing Ottoman control in the eastern Mediterranean motivated Portuguese and Spanish explorers to turn toward the Atlantic in hopes of reaching the rich trading posts of China and the Indian Ocean by another route. Ottoman expansion was made possible by the Ottomans’ domination of Afro-Eurasian trade routes as they recovered in the wake of the Black Death, and it was marked by the sultanate’s co-optation of local elites and a relatively tolerant attitude toward other peoples and religions.

For the Europeans, in contrast, expansion overseas was quite new and experimental. Mariners and traders, searching for new routes to South and East Asia, began exploring the Atlantic coast of Africa. Lured by the prospect of spices, silks, and the enslaved, and aided by new maritime technology, Portuguese expeditions made their way around Africa and onward to India. Although Europeans still had little to offer would-be trading partners in Asia, their developing capability in overseas trade laid the foundations for a new kind of global commerce.

Both the new and the old expansionism knitted worlds together that had previously been apart or only loosely interconnected. Together they laid the foundations for a new chapter in world history. But we must not forget that even in the midst of this global transformation, the peoples of each continent continued to focus on local, and often religious, struggles closer to their everyday lives.

Trade all across Afro-Eurasia benefited enormously from China’s economic dynamism, which was driven primarily by China’s vast internal economy. Chinese demand for silver fueled a revival of trade across the Indian Ocean and traditional overland routes. After the Ming dynasty relocated its capital from Nanjing in the prosperous south to the northern city of Beijing, Chinese merchants, artisans, and farmers exploited the surging domestic market. Reconstruction of the Grand Canal now opened a major artery that allowed food and riches from the economically vibrant lower Yangzi area to reach the capital region of Beijing. Urban centers, such as Nanjing with a population approaching a million and Beijing at half a million, became massive and lucrative markets. Despite official restrictions on trade, merchants thrived and coastal cities remained active harbors. (See Map 12.5.)

What did foreign buyers have to trade with the Chinese? The answer was silver, which became essential to the Ming monetary system. Whereas their predecessors had used paper money, Ming consumers and traders mistrusted anything other than silver or gold for commercial dealings. Once the rulers adopted silver as a means of tax payment in the 1430s, it became the predominant medium for larger transactions. China, however, did not produce sufficient silver for its booming economy. Indeed, silver and other precious metals were about the only commodities for which the Chinese would trade their precious manufactures. Through most of the sixteenth century, China’s main source of silver was Japan, which one Florentine merchant called the “silver islands.” After the 1570s, however, the Philippines, now under the control of the Spanish, became a gateway for silver coming from the New World. One-third of all silver mined in the Americas during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries wound up in Chinese hands.

China’s economic expansion contributed to the revival of Indian Ocean trade. Long-distance merchants developed a brisk commerce that tied the whole of the Indian Ocean together. Ports as far off as East Africa and the Red Sea enjoyed links with coastal cities of India, South Asia, and the Malay Peninsula. Muslims dominated this trade. India was the geographic and economic center of numerous trade routes. With a population expanding as rapidly as China’s, its large cities (such as Agra, Delhi, and Lahore) each boasted nearly half a million residents. India’s manufacturing center, Bengal, exported silk and cotton textiles and rice throughout South and Southeast Asia. Like China, India exported more than it imported, selling textiles and pepper in exchange for silver.

Overland commerce also thrived anew. One well-trafficked route linked the Baltic Sea, Muscovy, the Caspian Sea, the central Asian oases, and China. Other land routes carried goods to the ports of China and the Indian Ocean; from there, they crossed to the Ottoman Empire’s heartland and went by land farther into Europe. Ottoman authorities took a keen interest in the caravan trade, since the state gained considerable tax revenue from it. To facilitate the caravans’ movement, the government maintained refreshment and military stations along the route. The largest had individual rooms to accommodate the chief merchants and could provide lodging for up to 800 travelers, as well as care for all their animals. But gathering so many traders, animals, and cargoes could also attract marauders, especially desert tribesmen. To stop the raids, authorities and merchants offered cash payments to tribal chieftains as “protection money.” This was a small price to pay in order to protect the caravan trade, whose revenues ultimately supported imperial expansion.

Having built the period’s most powerful military forces and armed themselves with the latest maps and scientific instruments, the Ottomans began the sixteenth century in possession of Constantinople and great swaths of southeastern Europe and Anatolia. During the sultanate of Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566), Ottoman forces carried the empire southward into Egypt, eastward to the Iranian borderlands, and westward into Europe. By 1550, the Ottoman Empire stretched from Hungary and the Crimea in the north to the Arabian Peninsula in the south, from Morocco in the west to the contested border with Safavid Iran in the east. (See Map 12.1 and Chapter 13.)

The Ottomans had become a world power, and their armada dwarfed that of all others at the time. It consisted of seventy-four ships, including twenty-seven large and small galleys and munitions ships, mounted with cannons. Piri Reis—an Ottoman admiral and cartographer—conducted research in the Indian Ocean, an area previously unknown to the Ottomans. Not only did he produce a map of the world, but in 1526 he presented to Sultan Suleiman a masterpiece of geography and cartography known as The Book of the Sea. The book drew on Arab sources as well as Indian maps obtained from the Portuguese and offered full information on the geography of the world. In no small part thanks to Piri, the Ottomans made important gains in the Red Sea and ventured into the Indian Ocean as rivals to the Portuguese. But their main energies were devoted to the lands around the eastern Mediterranean, the Black Sea, and the Arabian Peninsula.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, sailors from Portugal, Spain, England, and France explored and mapped the coastline of most of the world. Their activities took place in the shadow of the leading empires of the day, with the Ottomans, Safavids, Mughals, and Ming largely unconcerned and unthreatened by them. They established contacts and made connections that, over time, became increasingly important.

The conquest of Syria and Egypt in 1516–1517 was decisive in allowing Ottoman leaders to regard their Sunni state as the preeminent Muslim empire from that moment forward, even enabling some sultans to call themselves caliphs. Egypt became the Ottomans’ most lucrative and important acquisition, the breadbasket of the empire and the province that provided Istanbul with the largest revenue stream. But the conquest was no easy matter. The Mamluk rulers resisted mightily, losing a bloody battle in 1516 at Marj Dabiq, north of Aleppo, after which, according to Ibn Iyas, the Arab chronicler of the age, “the battlefield was strewn with corpses and headless bodies and faces covered with dust and grown hideous.” Nor did the conquest of Egypt prove any easier, for the Mamluks were determined to hold on to their most precious possession. The conquest of Constantinople and the Arab lands transformed the Ottoman Empire, creating a Muslim majority in an empire once mainly populated by conquered Christians and enabling Ottoman sultans to see themselves as heirs of a long line of empires that had ruled over these regions.

Yet on the eastern front, in conflicts with the Safavid Empire, the Ottomans encountered their earliest military failures and their most determined foe, an enemy state that plagued the Ottoman Empire until its collapse early in the eighteenth century (see Chapters 11 and 13). Blocked from eastward expansion, the Ottomans moved westward into Europe, which terrified Europeans. Having taken Constantinople in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II took Athens in 1458. The Ottomans also took large swaths of Balkan territory before turning to North Africa and Egypt and exerted more control than ever over commerce in the Mediterranean.

Core Objectives

ANALYZE the factors that enabled Europeans to increase their trade relationships with Asian empires, and ASSESS their significance.

Ottoman conquests in southeastern and central Europe resulted in the subordination of Christians and Jews to Muslim rule. Centuries of Ottoman rule left a multiethnic legacy in places like Bosnia, including large populations of Muslims in areas later taken by the Habsburg Empire. Thus, the Ottomans, too, from the eastern end of the Mediterranean, became key players in the transformation of Europe in the age of da Gama and Columbus.

Sea Routes to Asia

Sea Routes to Asia

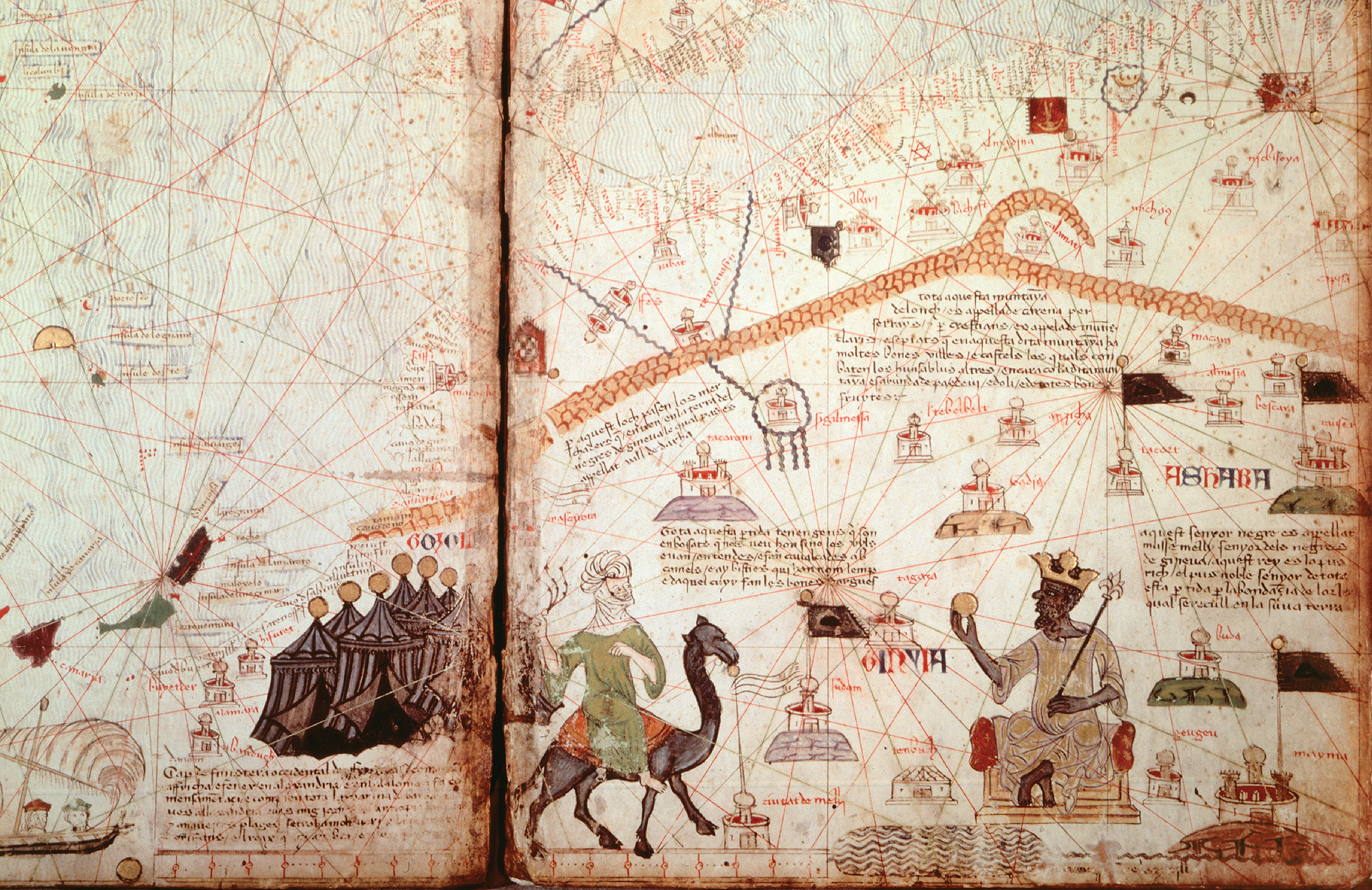

The emergence of the Ottoman Empire prompted Europeans to find new links to the east in the sixteenth century. When the Ottomans took control of traditional overland trade routes from Europe to Asia, Europeans began to look south and west—and ventured across the seas. (See again Map 12.1.) The Portuguese took the lead. Their search for new routes to Asia led them first to Africa. Europeans had long believed that Africa was a storehouse of precious metals. In fact, a fourteenth-century map, the Catalan Atlas, had depicted a single black ruler controlling a vast quantity of gold in the interior of Africa. As the price of gold skyrocketed during and after the Black Death, ambitious men decided to venture southward in search of this commodity and its twin, silver. While precious metals initially drove Portuguese interest in Africa’s Atlantic coast, it would be the development of the sugar plantations on the islands they controlled off the African coast (the Canaries, Cape Verde, and Madeira, then São Tomé and Principe in the Gulf of Guinea) and the need for enslaved labor to work on those plantations that would come to dominate trade with African kingdoms during the sixteenth century. In order to trade European goods in exchange for enslaved humans, the Portuguese built trading forts along major regions of Africa’s west coast, establishing trading relationships with prominent African kingdoms and rulers extending southward from Senegambia in the north through Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast, the Kongo kingdom, and Angola. This initial version of the African slave trade would expand dramatically in later centuries to fuel the development of the European colonies in the New World. Once European merchants had found sea routes around Africa and established a flourishing trade with the Atlantic kingdoms, they sought to reap the riches abounding in Asian ports, especially when Asian states were firmly established across the Indian Ocean in the seventeenth century.

Innovations in maritime technology and information from other mariners helped Portuguese sailors navigate the treacherous waters along the African coast. New vessels included the carrack, a three- or four-masted ship, developed by the Portuguese to deal with rough waters like the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean. The caravel, with specially designed triangular sails, enabled European sailors to nose in and out of estuaries and navigate unpredictable currents and winds. By using highly maneuverable caravels and perfecting the technique of tacking (sailing into the wind rather than before it), the Portuguese advanced far along the West African coast. In addition, newfound expertise with the compass and the astrolabe helped navigators determine latitude.

Portuguese seafarers ventured from the coasts of Africa into the Indian Ocean and inserted themselves into its thriving commerce. In Asia, Portugal did not attempt to rule directly or to establish colonies. Rather, it aimed to exploit Asian commercial networks and trading systems. To do so, the Portuguese took advantage of a technology developed centuries earlier in China: gunpowder. Mounting small cannons on their warships, they bombarded ports and rival navies or merchant vessels.

The first Portuguese mariner to reach the Indian Ocean was Vasco da Gama (1469–1524). Like Columbus, da Gama was relatively unknown before his extraordinary voyage commanding four ships around the Cape of Good Hope. He found a network of commercial ties spanning the Indian Ocean, as well as skilled Muslim mariners who knew the currents, winds, and ports of call. Once established in the key ports, the Portuguese attempted to take over the trade or, failing this, to tax local merchants. From Sofala, Kilwa, and other important ports on the East African coast, from Goa and Calicut in India, and from Macau in southern China, the Portuguese soon dominated the most active sea-lanes of the Indian Ocean. The Portuguese did not interrupt the flow of luxuries among Asian and African elites; rather, their naval captains simply kept a portion of the profits for themselves, content to benefit from Asian prosperity without imposing Portuguese rule. Only with the discovery of the Americas and the conquest of Brazil did Portugal become an empire with large overseas colonies. For this to transpire, mariners would have to traverse the Atlantic Ocean itself.