Core Objectives

COMPARE the major features of world trade in Asia, the Americas, Africa, and Europe.

Core Objectives

COMPARE the major features of world trade in Asia, the Americas, Africa, and Europe.

While Europe was experiencing religious warfare, Asian empires were expanding and consolidating their power, and trade was flourishing. If anything, the arrival of European sailors and traders in the Indian Ocean strengthened trading ties across the region and enhanced the political power and expansionist interests of Asia’s imperial regimes. The Mughal ruler of India, Akbar, and the Ottoman sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent (see Chapter 11), were effective and esteemed rulers. The Ming dynasty’s elegant manufactures enjoyed worldwide renown, and its ability to govern vast numbers of highly diverse peoples led outsiders to consider China the model imperial state.

The Mughal Empire became one of the world’s wealthiest empires just when Europeans were establishing sustained connections with India. These connections, however, only touched the outer layer of Mughal India, one of Islam’s greatest regimes. Established in 1526, it was a vigorous, centralized state whose political authority encompassed most of modern-day India. During the sixteenth century, it had a population of between 100 and 150 million.

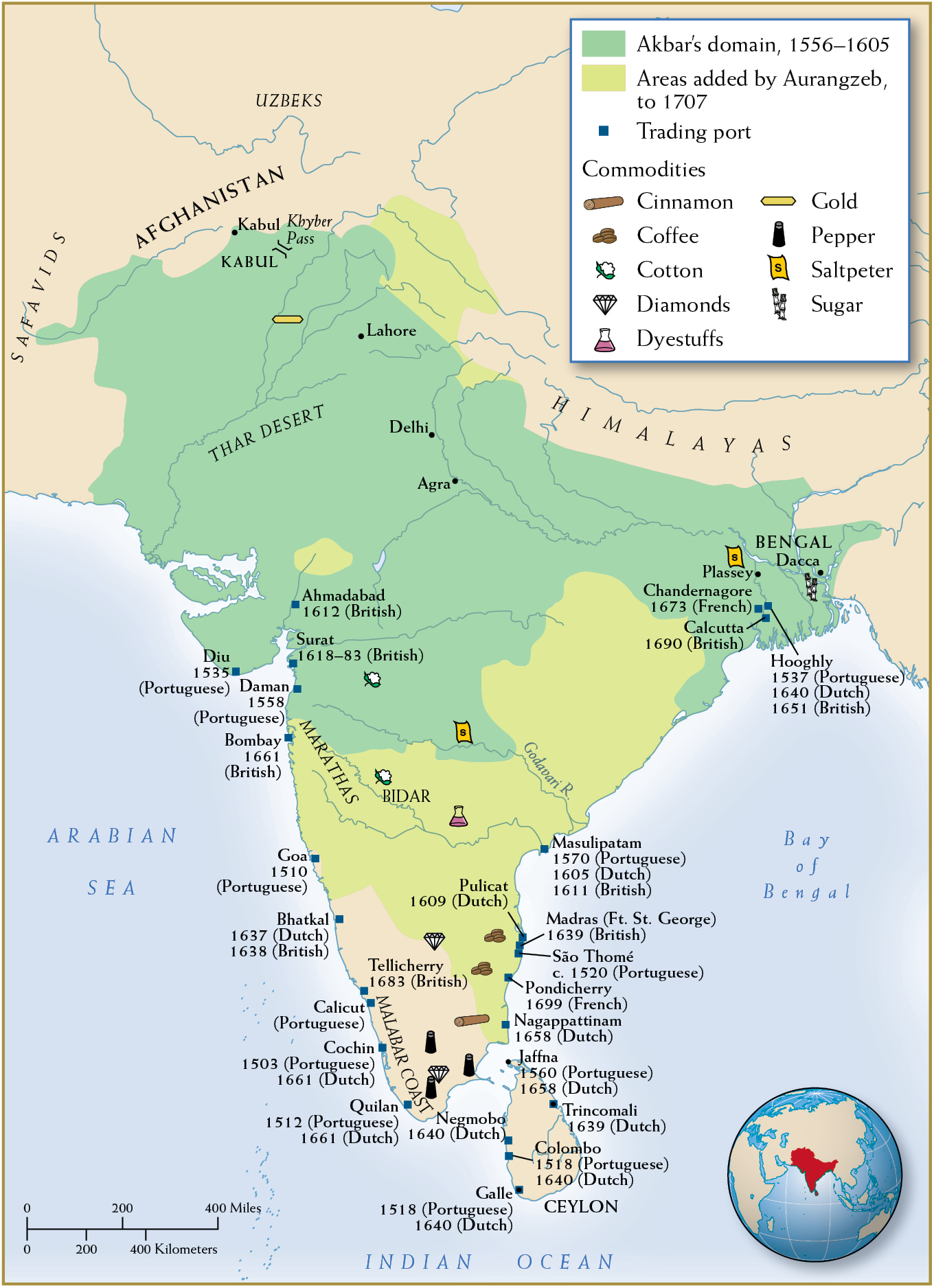

The Mughals’ strength rested on their military power. The dynasty’s founder, Babur, had introduced horsemanship, artillery, and field cannons from central Asia, and gunpowder had secured his swift military victories over northern India. Under his grandson, Akbar (r. 1556–1605), the empire enjoyed expansion and consolidation that continued (under his own grandson, Aurangzeb) until it covered almost all of India. (See Map 12.4.) Known as the “Great Mughal,” Akbar was skilled not only in military tactics but also in the art of alliance making. Deals with Hindu chieftains through favors and intermarriage also undergirded his empire.

Mughal rulers were flexible toward their realm’s diverse peoples, especially in spiritual affairs. Though its primary commitment to Islam stood firm, the imperial court also patronized other beliefs, displaying a tolerance that earned it widespread legitimacy. The contrast with Europe, where religious differences drove deep fractures within and between states, was stark. Unlike European monarchs, who tried to enforce religious uniformity, Akbar studied comparative religion and hosted regular debates among Hindu, Muslim, Jain, Parsi, and Christian theologians. His tolerance kept a multifaceted spiritual kingdom under one political roof.

During the sixteenth century, expanded trade with Europe brought more wealth to the Mughal polity, while the empire’s strength limited European incursions. Although the Portuguese occupied Goa and Bombay on the Indian coast, they had little presence elsewhere and dared not antagonize the Mughal emperor. In 1578, Akbar recognized the credentials of a Portuguese ambassador and allowed a Jesuit missionary to enter his court. Thereafter, commercial ties between Mughals and Portuguese intensified, but the merchants were still restricted to a handful of ports. In the 1580s and 1590s, the Mughals ended the Portuguese monopoly on trade with Europe by allowing Dutch and English merchantmen to dock in Indian ports.

Centered in northern India, the Mughal Empire used surrounding regions’ wealth and resources—military, architectural, and artistic—to glorify the court. Over time, the enhanced wealth caused friction between wealthy and poorer Indian regions, and even between merchants and rulers. Yet as long as merchants relied on rulers for their commercial gains, and as long as rulers balanced local and imperial interests, the realm maintained a formal unity and kept Europeans on its margins.

Under Akbar and Aurangzeb, the Mughal Empire expanded and dominated much of South Asia. Yet, by looking at the trading ports along the Indian coast, one can see the growing influence of Portuguese, Dutch, French, and English interests.

China also prospered from increased commerce in the late sixteenth century. Like the Mughals, the Ming seemed unconcerned with the increasing appearance of foreigners, including Europeans bearing silver. As in India, the Ming confined European traders to port cities. Silver from the Americas did, however, circulate widely in China. It allowed employers to pay their workers with money rather than with produce or goods, which in turn motivated those workers to produce more. China also experienced soaring production in agriculture and handicrafts. A cotton boom, for example, made spinning and weaving China’s largest industry.

One measure of greater prosperity under the Ming was its population surge. By the mid-seventeenth century, China’s population probably accounted for more than one-third of the total world population. Although 90 percent of Chinese people lived in the countryside, large numbers filled the cities. Beijing, the Ming capital, grew to over 1 million; Nanjing, the secondary capital, nearly matched that number. Cities offered diversions ranging from literary and theatrical societies to schools of learning, religious societies, urban associations, and manufactures from all over the empire. The elegance and material prosperity of Chinese cities dazzled European visitors. One Jesuit missionary described Nanjing as surpassing all other cities “in beauty and grandeur. . . . It is literally filled with palaces and temples and towers and bridges. . . . There is a gaiety of spirit among the people who are well mannered and nicely spoken.”

Urban prosperity fostered entertainment districts where people could indulge themselves anonymously and in relative freedom. Some Ming women found a place here as refined entertainers and courtesans, others as midwives, poets, sorcerers, and matchmakers. Female painters, mostly from scholar-official families, emulated males who used the home and garden for creative pursuits. The expanding book trade also accommodated women, who were writers as well as readers, not to mention literary characters and archetypes (especially of Confucian virtues). But Chinese women made their greatest fortunes inside the emperor’s Forbidden City as healers, consorts, and power brokers. The vitality that commerce brought to Ming society continued even after the dynasty’s fall in 1644, laying the foundation for further population growth and territorial expansion.

As actors in the world of Asian commerce, Europeans were the newest, and weakest, kids on the block. Europeans’ overseas expansion had originally looked toward Asia in hopes of acquiring greater access to luxury goods such as silk and spices. It took some time for them to acquire access to these markets. But silver, followed by maritime and military advances and state-backed trading companies, offered Europeans the opportunity to gradually insert themselves into the Eurasian luxury trade. They did not conquer it; before the advent of the industrial revolution, Europeans grafted onto Asian commercial networks and their powerful actors.

The Portuguese blazed the way as collectors of customs duties from Asian traders and, after 1557, as trans-shippers of Chinese porcelains and silks from the coastal enclave of Macau. (See Map 12.5.) The Portuguese also dominated the silver trade from Japan. Envying Portuguese profits, the Spanish, English, and Dutch also ventured into Asian waters.

The real breakthrough came when the American silver supply got hitched directly to Asian silver demand—and Europeans could play the intermediaries. With its monopoly on American silver, Spain enjoyed a competitive advantage. In 1565, the first Spanish trading galleon reached the mouth of the Pasig River on one of the islands in the current-day Philippines. The town of Maynila was a vibrant marketplace in 1570. Merchants from China and Borneo did a swift business there, trading in gold, beeswax, porcelains, and forest products. Maynila was a strategic spot on the sea routes that connected China, Japan, and the Spice Islands—the exclusive source of prized nutmeg and cloves. The Spanish eyed the town not from Europe, but from the other side of the Pacific, in Mexico. Officials and adventurers mortgaged their fortunes in Mexico to fund an expedition to Maynila, taking control of the chieftainship after a series of skirmishes. Thus, in 1571, was born Manila, an administrative dependency of distant Mexico and eventually the capital of the Philippines, the Spanish colony named after the king, Philip II.

The Ming Empire in the early seventeenth century was the world’s most populous state and arguably its wealthiest.

Taking Manila opened up a direct portal to China. Each year, ships from Peru and Mexico crossed the Pacific to Manila bearing cargoes of silver. They returned with a ballast of porcelains and silks. Merchants in Manila also procured silks, tapestries, and feathers from the China seas for shipment to the Americas, where the mining elite eagerly awaited these imports.

Cultural sharing and influences were not limited to just trade. Mexican theater groups represented the work of the great writer Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz on a Manila stage. Africans and Filipinos joined the same religious brotherhoods in Mexico and Manila. Filipino migrants taught Mexican Indians how to produce wine from palm trees. Even Chinese migrants and traders joined the flow from Manila to Mexico. In 1635, Spanish barbers in the Viceroyalty complained that a glut of cheap Chinese hair and beard trimmers was driving them out of business. Not only did the Chinese barbers’ stalls around the Plaza Mayor offer discounts, but they also provided acupuncture, bloodletting, and coveted Chinese herbal medicines. Missions as far away as California boasted lavish silk vestments brought back on the galleons from Manila. Spain’s conquests of Manila and Mexico created a booming Pacific world system.

The year 1571 was decisive in the history of the modern world, for in that year Spain inaugurated a trade circuit that made good on Ferdinand Magellan’s earlier achievement of circumnavigating the globe. As Spanish ships circled the globe from the New World to China and from China back to Europe, the world became commercially interconnected. Silver solidified the linkage, as it was the only foreign commodity for which the Chinese had an insatiable demand. From the mother lodes of the Andes and Mesoamerica, silver made the commerce of the world go round. Between 1500 and 1800, the Spanish colonies pumped out 150,000 tons of silver, dwarfing all other supplies combined; much of it sailed east, directly to Asia to monetize and fuel its commercial boom. The silver also coursed through European trading systems and financiers’ accounts, growing Europe’s economy—despite the political and religious mayhem. Though the Dutch were caught in an endless war with Spanish and Portuguese forces, business was lucrative enough that blue and white Chinese porcelain became commonplace on dinner tables in Amsterdam. Soon, there were imitation items made in Europe, later called “chinoiserie.” Whether imported or imitation, Chinese styles became all the rage among prosperous European urbanites. Well-to-do aristocratic women had to be seen in the finest—and latest—of Chinese silks.

By creating an interconnected trading system and finding the means for Europeans to trade with Asian suppliers of precious commodities, the Spanish and the Portuguese created the first world market. It was increasingly integrated. But it also set off a scramble and ramped up competition from envious latecomers. Bristling with their Protestant faiths and determined to muscle in on the Iberian empires’ terrain and traffic, the English and the Dutch reached the South China Sea late in the sixteenth century. Captain James Lancaster made the first English voyage to the East Indies between 1591 and 1594. Five years later, 101 English subscribers pooled their funds and formed a joint-stock company (an association in which each member owns shares of capital). This English East India Company soon won a royal charter granting it exclusive rights to import East Indian goods. Soon the company displaced the Portuguese in the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf. Doing a brisk trade in indigo, saltpeter, pepper, and cotton textiles, the English East India Company eventually acquired control of ports on both coasts of India—Fort St. George (Madras; 1639), Bombay (1661), and Calcutta (1690).

Though they fought among themselves for toeholds and trade, Europeans trading in Asia remained dependent on local power brokers and commercial traders. The number of European settlers was miniscule, their cultural inroads few. Trade in Asia continued, largely in Asian hands, and focused on older routes. Although Europeans came to control some small coastal enclaves, they did not have large colonial lands to rule. In Asia, Europeans were, for all intents and purposes, consigned to the role of intermediaries or predators. This contrasted with the Atlantic world, where Europeans created trading and colonizing systems that placed them increasingly at the center—and buoyed their fledgling empires.