How Old Is the Earth?

Hominins to Modern Humans

The modern scientific creation narrative of human evolution would have been unimaginable even just over a century ago, when Charles Darwin was formulating his ideas about human origins. As we will see in this section, scientific discoveries continue to show that modern humans evolved from earlier hominins. Through adaptation to their environment, various species of hominins developed new physical characteristics and distinctive skills. Millions of years after the first hominins appeared, the first modern humans—Homo sapiens—emerged and spread out across the globe.

Evolutionary Findings and Research Methods

New insights into the time frame of the universe and human existence have occurred over centuries. Geologists made early breakthroughs in the eighteenth century when their research into the layers of the earth’s surface revealed a world much older than biblical time implied. Evolutionary biologists, most notably Charles Darwin (1809–1882), concluded that all life had evolved over long periods from simple forms of matter. In the twentieth century, astronomers, evolutionary biologists, and archaeologists developed sophisticated dating techniques to pinpoint the chronology of the universe’s creation and the evolution of all forms of life on earth. And in the early twenty-first century, paleogenomic researchers are recovering full genomic sequences of extinct hominins (such as the Neanderthals) and using ancient DNA to reconstruct the full skeletons of human ancestors and relatives (such as the Denisovans) of whom only a few bones have survived. Their discoveries have radically transformed humanity’s understanding of its own history (see Current Trends in World History: Using Big History and Science to Understand Human Origins). A mere century ago, who would have accepted the idea that the universe came into being 13.8 billion years ago, that the earth appeared about 4.5 billion years ago, and that the earliest life-forms began to exist about 3.8 billion years ago?

Yet, modern science suggests that human beings are part of a long evolutionary chain stretching from microscopic bacteria to African apes that appeared about 23 million years ago, and that Africa’s “Great Ape” population separated into several distinct groups of hominids: one becoming present-day gorillas; the second becoming chimpanzees; and the third becoming modern humans only after following a long and complicated evolutionary process. Our focus will be on the third group of hominids, namely the hominins who became modern humans. A combination of traits, evolving over several million years, distinguished humans from other hominids, including (1) lifting the torso and walking on two legs (bipedalism), thereby freeing hands and arms to carry objects and hurl weapons; (2) controlling and then making fire; (3) fashioning and using tools; (4) developing cognitive skills and an enlarged brain and therefore the capacity for language; and (5) acquiring a consciousness of “self.” All these traits were in place at least 150,000 years ago.

Two terms central to understanding any discussion of hominin development are evolution and natural selection. Evolution is the process by which species of plants and animals change and develop over generations, as certain traits are favored in reproduction. The process of evolution is driven by a mechanism called natural selection, in which members of a species with certain randomly occurring traits that are useful for environmental or other reasons survive and reproduce with greater success than those without the traits. Thus, biological evolution (human or otherwise) does not imply progress to higher forms of life, but instead implies successful adaptation to environmental surroundings.

CORE OBJECTIVES

TRACE the major developments in hominin evolution that resulted in the traits that make Homo sapiens “human.”

Early Hominins, Adaptation, and Climate Change

Skulls, Tools, and Fire

It was once thought that evolution is a gradual and steady process. The consensus now is that evolutionary changes occur in punctuated bursts after long periods of stasis, or non-change. These transformative changes were often brought on, especially during early human development, by dramatic alterations in climate and by ruptures of the earth’s crust caused by the movement of tectonic plates below the earth’s surface. The heaving and decline of the earth’s surface led to significant changes in climate and in animal and plant life. Also, across millions of years, the earth’s climate was affected by slight variations in the earth’s orbit, the tilt of the earth’s axis, and the earth’s wobbling on its axis.

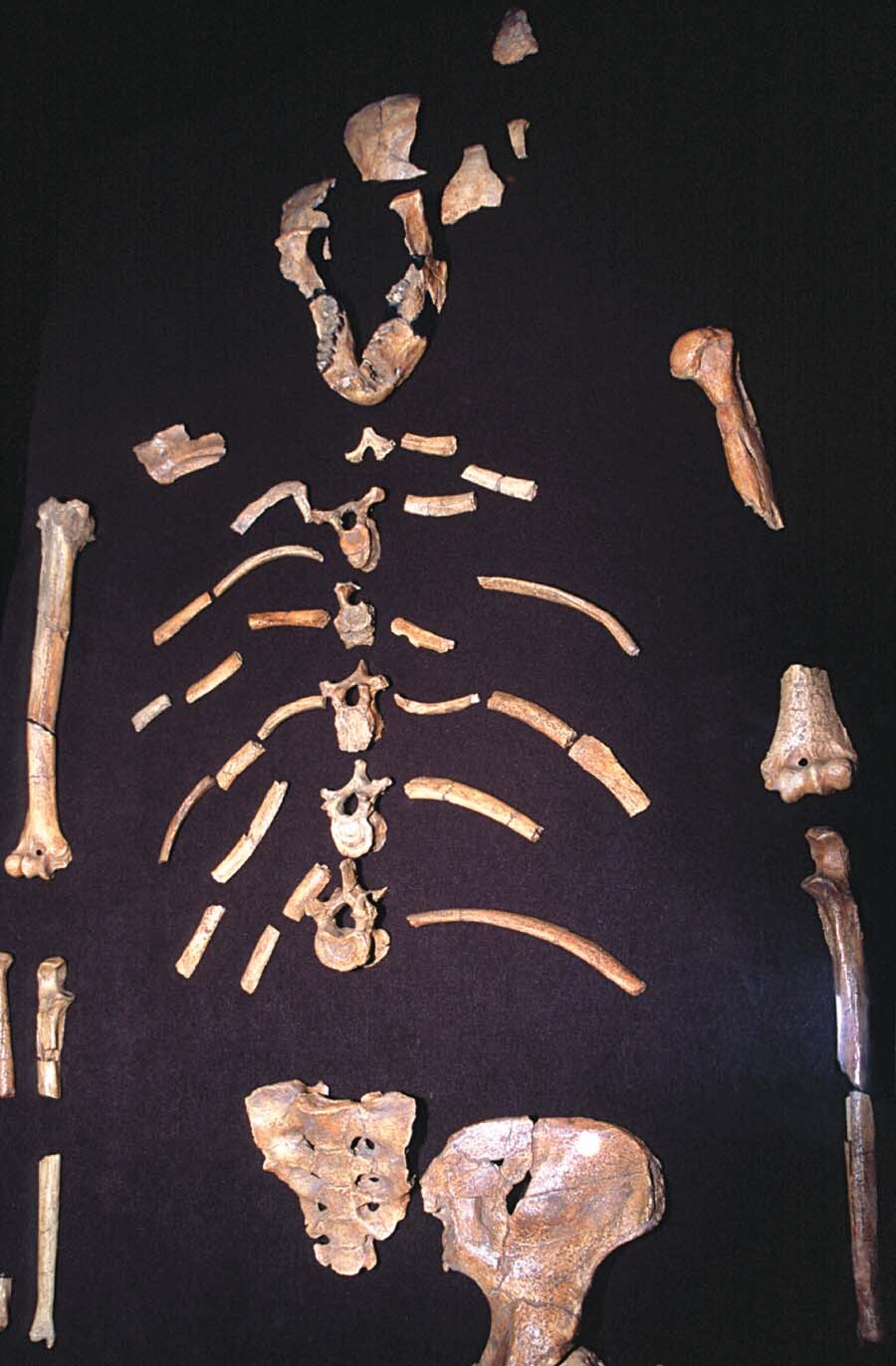

AUSTRALOPITHECINES As the earth experienced these immense changes, what was it like to be a hominin in the millions of years before the emergence of modern humans? An early clue came from a discovery made in 1924 at Taung, not far from the present-day city of Johannesburg, South Africa. A twenty-nine-year-old scientist named Raymond Dart identified the pint-sized skull and bones of a creature, nicknamed “Taung child,” that had both ape-like and humanoid features. Dart officially labeled his bipedal find Australopithecus africanus. Australopithecines existed not only in southern Africa but in the north as well. In 1974, an archaeological team under the leadership of Donald Johanson unearthed a relatively intact skeleton of a young adult female australopithecine near the Awash River in present-day Ethiopia. While the technical name for the find became Australopithecus afarensis, the researchers who found the skeleton gave it the nickname Lucy, based on the then-popular Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

Current Trends in World History

Using Big History and Science to Understand Human Origins

The history profession has undergone transformative changes since the end of World War II. One of the most radical changes in historical narratives is what historian David Christian has called “Big History.” Just what it is still remains a mystery for many historians, and few departments of history offer courses in Big History. But Big History presents a coherent narrative of the origins of the universe up to the present. Its influence on our sense of who we are and where we came from is impressive.

Big History covers the history of our universe from its creation 13.8 billion years ago to the present. (See Table 1.1.) Because it merges natural history with human history, its study requires knowledge of many fields of science. Big History’s use of the sciences enables us to learn of the universe before our solar system (astrophysics), our planet before life (geology), life before humans (biology), and humans before written sources (paleoanthropology). At present, few historians feel comfortable using these findings or integrating these data into their own general history courses. Nevertheless, Big History provides another narrative of how and when our universe, and we as human beings, came into existence.

Most of this chapter deals with how our species, Homo sapiens, came into being, and here, too, scholars are dependent on a range of approaches, including the work of linguists, biologists, paleoanthropologists, archaeologists, geneticists, and many others. The first major advance in the study of the time before written records occurred in the mid-twentieth century, and it involved the use of radiocarbon dating. All living things contain the radiocarbon isotope C14, which plants acquire directly from the atmosphere and animals acquire indirectly when they consume plants or other animals. When these living things die, the C14 isotope begins to decay into a stable nonradioactive element, C12. Because the rate of decay is regular and measurable, it is possible to determine the age of fossils that leave organic remains for up to 40,000 years.

More information

A researcher sits on the ground at an archeological site. She is holding a knife in one hand and holding something in the ground with the other hand.

The evidence for human evolution, discussed in this chapter, requires dating methods that can extend back much farther than radiocarbon dating. Using the potassium-argon method, scientists can calculate the age of nonliving objects by measuring the ratio of potassium to argon in them, since potassium decays into argon. This method allows scientists to calculate the age of objects up to 1 million years old. Likewise, scientists can use uranium-thorium dating to determine the date of objects (like shells, teeth, and bones) more closely linked to living beings. This uranium-series method permits scientists to date objects up to 500,000 years old. A similar date limit can be reached through thermoluminescence methods applied to soil deposits and objects with crystalline materials that have been exposed to sunlight or heat (as in the flames of a fire pit or the heat of a kiln). Even if a scientist cannot offer a direct date for an object—teeth, skull, or other bone—such methods offer a date for the sediments in which researchers find fossils, as a gauge of the age of the fossils themselves.

As this chapter demonstrates, the environment, especially climate, played a major role in the appearance of hominins and the eventual dominance of Homo sapiens. But how do we know so much about the world’s climate so far back in time? This brings us to yet another scientific breakthrough, known as marine isotope stages. By exploring the marine life, mainly pollen and plankton, deposited in deep seabeds and measuring the levels of oxygen-16 and oxygen-18 isotopes in these life-forms, oceanographers and climatologists can determine the temperature of the world hundreds of thousands and even millions of years ago and thus chart the cooling and warming cycles of the earth’s climate.

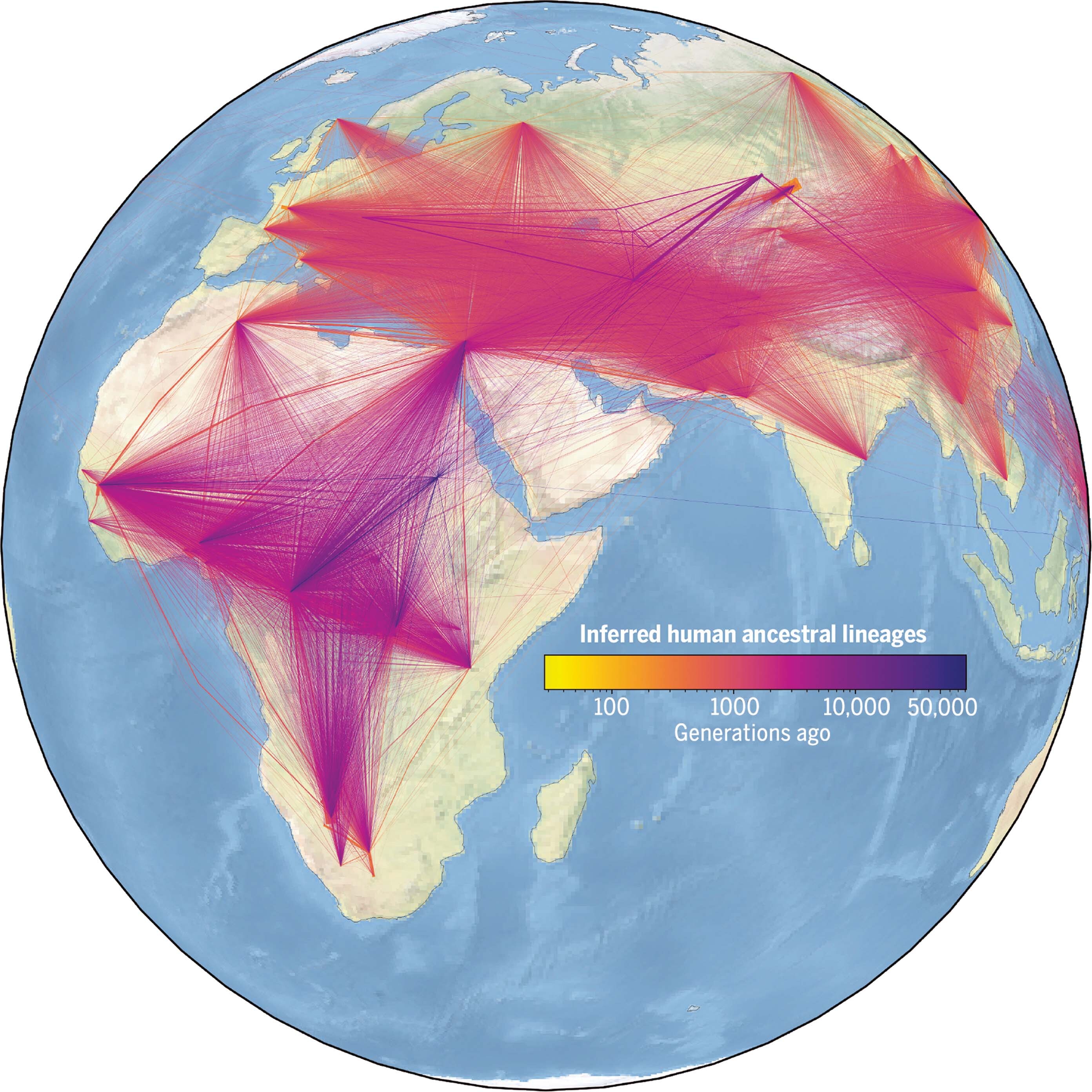

DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) analysis is another crucial tool for unraveling the beginnings of modern humans. DNA, which determines biological inheritances, exists in two places within the cells of all living organisms—including the human body. Nuclear DNA (nDNA) and mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) exist in males and females, but only mitochondrial DNA from females passes to their offspring, as the females’ egg cells carry their mitochondria with their DNA to the offspring. By examining mitochondrial DNA, researchers can measure genetic relatedness and variation among living organisms—including human beings. Such analysis has enabled researchers to pinpoint human descent from an original African population and to determine various branches of Homo sapiens lineage.

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is opening up new avenues for research on early human ancestors. Paleogeneticists can use aDNA to reconstruct physical traits of long-extinct human ancestors for whom only a skull, or jaw, or finger bone may have been found. Teams of scientists, perhaps most notably the lab led by David Reich at Harvard, have developed methods for extracting aDNA and using computers and statistics to reconstruct a full genetic sequence. aDNA findings by Reich, Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute, and others are challenging long-held assumptions about human origins hundreds of thousands of years ago and, more recently, human migrations such as those of Indo-Europeans and Pacific Islanders.

The genetic similarity of modern humans suggests that the population from which all Homo sapiens descended originated in Africa more than 250,000 years ago. When these humans began to move out of Africa as long as 180,000 years ago, they spread eastward into Southwest Asia and then throughout the rest of Afro-Eurasia. One group migrated to Australia about 50,000 years ago. Another group moved into Europe about 40,000 years ago. When the scientific journal Nature in 1987 published genetic-based findings about humans’ spread across the planet, it inspired a groundswell of public interest—and a contentious scientific debate that continues today.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- How has the study of prehistory changed since the mid-twentieth century?

- Why are different dating methods appropriate for different kinds of artifacts?

- How does the study of climate and environment relate to the origins of humans?

EXPLORE FURTHER

Barham, Lawrence, and Peter Mitchell, The First Africans: African Archaeology from the Earliest Toolmakers to Most Recent Foragers (2008).

Barker, Graeme, Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory: Why Did Foragers Become Farmers? (2006).

Christian, David, Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History (2004).

Lewis-Kraus, Gideon, “Is Ancient DNA Research Revealing New Truths—or Falling into Old Traps?” New York Times Magazine, January 17, 2019.

Reich, David, Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past (2018).

|

TABLE 1.1 | The Age of the Universe and Human Evolution |

|||

|

DEVELOPMENT |

TIME |

||

|

Big-bang moment in the creation of the universe |

13.8 BILLION YEARS AGO (BYA) |

||

|

Formation of the sun, earth, and solar system |

4.5 BYA |

||

|

Earliest life-forms appear |

3.8 BYA |

||

|

Multicellular organisms appear |

1.5 BYA |

||

|

First hominids appear |

7 MILLION YEARS AGO (MYA) |

||

|

Australopithecus afarensis appear (including Lucy) |

3.9 MYA |

||

|

Homo habilis appear (including Dear Boy) |

2.5 MYA |

||

|

Homo erectus appear (including Java and Peking Man) |

1.8 MYA |

||

|

Homo erectus leave Africa |

1.5 MYA |

||

|

Neanderthals appear (in Eurasia) |

c. 400,000 YEARS AGO |

<1% of Earth’s Existence |

|

|

Denisovans appear (in China and Siberia) |

c. 400,000 YEARS AGO |

||

|

Homo sapiens appear |

300,000 YEARS AGO |

||

|

Homo sapiens leave Africa |

180,000 YEARS AGO |

||

|

Homo sapiens migrate into Asia |

120,000 YEARS AGO |

||

|

Homo sapiens migrate into Australia |

60,000 YEARS AGO |

||

|

Homo sapiens migrate into Europe |

50,000 YEARS AGO |

||

|

Homo sapiens migrate into the Americas |

23,000 YEARS AGO |

||

|

Homo sapiens sapiens appear (modern humans) |

35,000 YEARS AGO |

||

|

Before the agricultural revolution, dates are usually marked as BP, which counts the number of years before the present. These BP (or “before the present”) dates might also be assigned units such as BYA (billions of years ago), MYA (millions of years ago), or KA (thousands of years ago), depending on what scale is most appropriate for the development being described. More recent dates, beginning around 12,000 years ago, are marked with BCE (before [the] Common Era) as the unit of time. To render a BP date into a BCE date, simply subtract 2,000 years to account for the 2,000 years of the Common Era (CE). So 12,000 BP = 10,000 BCE (plus the 2,000 years of the Common Era since the year 1). |

|||

Lucy was remarkable. She stood a little over 3 feet tall, she walked upright, her skull contained a brain within the ape size range (that is, one-third human size), and her jaw and teeth were human-like. Her arms were long, hanging halfway from her hips to her knees—suggesting that she might not have been bipedal at all times and sometimes resorted to arms for locomotion, in the fashion of a modern baboon. Above all, Lucy’s skeleton was relatively complete and showed us that hominins were walking around more than 3 million years ago. Australopithecines were not humans, but they carried the genetic and biological material out of which modern humans would later emerge. These precursors to modern humans had a key trait for evolutionary survival: they were remarkably good adapters. They could deal with dynamic environmental shifts, and they were intelligent.

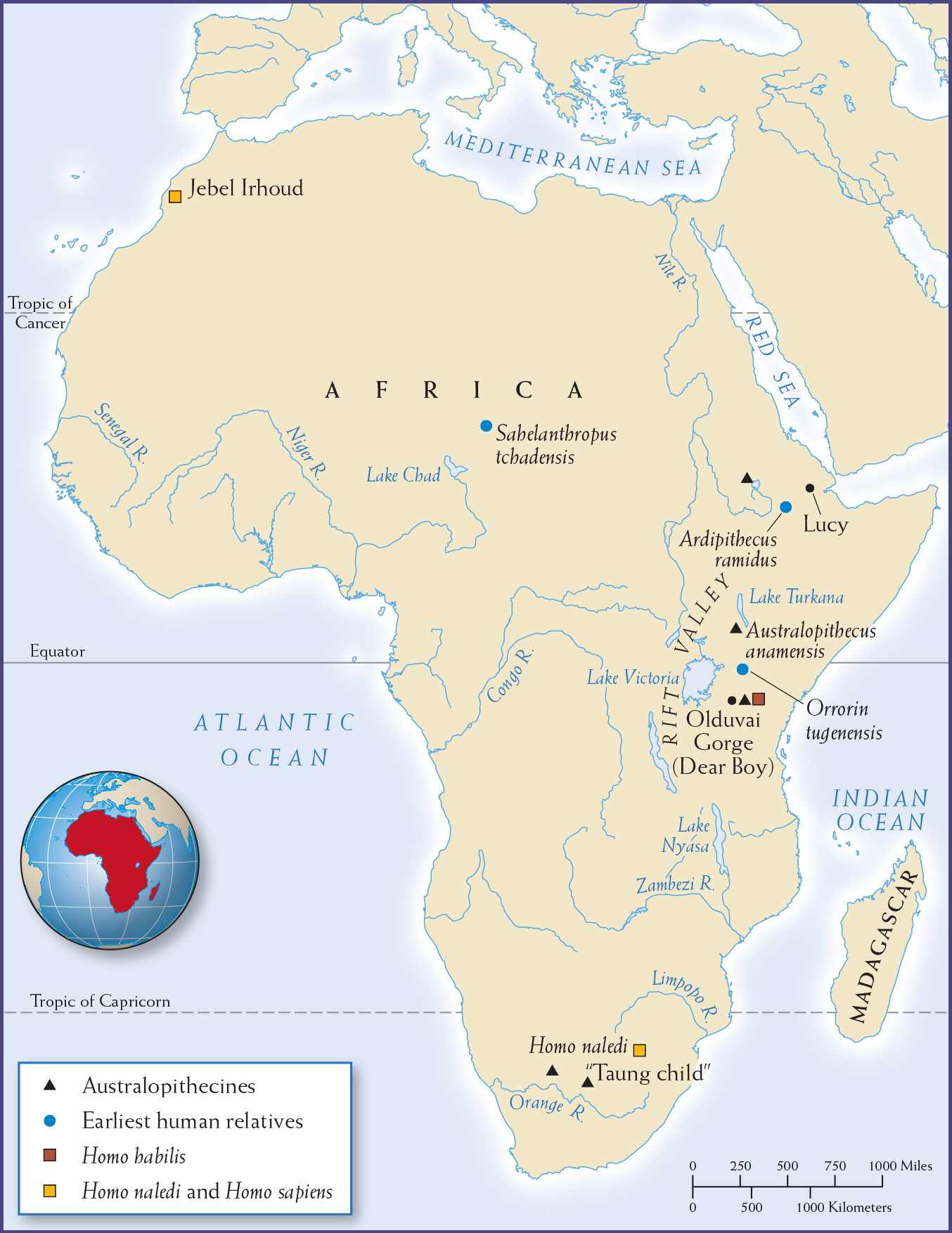

ADAPTATION For hominins, like the rest of the plant and animal world, survival required constant adaptation (the ability to alter behavior and to innovate, finding new ways of doing things). During the first millions of years of hominin existence, these slow changes involved primarily physical adaptations to the environment. The places where researchers have found early hominin remains in southern and eastern Africa had environments that changed from being heavily forested and well watered to being arid and desertlike, and then back again. (See Map 1.1.) Hominins had to keep pace with these changing physical environments or else risk extinction. In fact, many of the early hominin groups did die out.

In adapting, early hominins began to distinguish themselves from other mammals that were physically similar to them. It was not their hunting prowess that made the hominins stand out, because plenty of other species chased their prey with skill and dexterity. The single trait that gave early hominins a real advantage for survival was bipedalism: they became “two-footed” creatures that stood upright. At some point, the first hominins were able to remain upright and move about, leaving their arms and hands free for other useful tasks, like carrying food over long distances. Once they ventured into open savannas (grassy plains with a few scattered trees), about 1.7 million years ago, hominins had a tremendous advantage. They were the only primates (an order of mammals consisting of man, apes, and monkeys) to move consistently on two legs. Because they could move continuously and over great distances, they were able to migrate out of hostile environments and into more hospitable locations.

More information

Fossil bones of Lucy lay out on a table. They are arranged similar to a human skeleton but many pieces are missing.

CLIMATE CHANGES The climate in eastern and southern Africa, where hominin development began, was conducive to the development of diverse plant and animal species. When the world entered its fourth great ice age approximately 40 million years ago, the earth’s temperatures dropped and its continental ice sheets, polar ice sheets, and mountain glaciers expanded. We know this because during the last several decades paleoclimatologists have used measurements of ice cores and oxygen isotopes in the ocean to chart the often-radical changes in the world’s climate. The fourth great ice age lasted until 12,000 years ago. Like all ice ages, it had alternating warming and cooling phases that lasted between 40,000 and 100,000 years each. Between 10 and 12 million years ago, the climate in Africa went through one such cooling and drying phase. To the east of Africa’s Rift Valley, stretching from South Africa north to the Ethiopian highlands, the cooling and drying forced forests to contract and savannas to spread. It was in this region that some apes left the shelter of the trees, stood up, and learned to walk, to run, and to live in savanna lands—thus becoming the precursors of humans and distinctive as a new species. Using two feet for locomotion augmented their means for obtaining food and avoiding predators and improved their chances of survival in constantly changing environments.

In addition to being bipedal, hominins had opposable thumbs. This trait, shared with other primates, gave hominins great physical dexterity, enhancing their ability to explore and to alter materials found in nature. Manual dexterity and standing upright also enabled them to carry young family members if they needed to relocate, or to throw missiles (such as rocks and sticks) with deadly accuracy to protect themselves or to obtain food.

Hominins used their increased powers of observation and memory, what we call cognitive skills, to gather wild berries and grains and to scavenge the meat and marrow of animals that had died of natural causes or as the prey of predators. All primates are good at these activities, but hominins came to excel at them. Cognitive skills, which also included problem solving and—eventually—language, were destined to become the basis for further developments. Early hominins were highly social. They lived in bands of about twenty-five individuals, trying to survive by hunting small game and gathering wild plants. Not yet a match for large predators, they had to find safe hiding places. They thrived in places where a diverse supply of wild grains and fruits and abundant wildlife ensured a secure, comfortable existence. In such locations, small hunting bands of twenty-five could swell through alliances with others to as many as 500 individuals. Like other primates, hominins communicated through gestures, but they also may have developed a very basic form of spoken language that led (among other things) to the establishment of rudimentary cultural codes such as common rules, customs, and identities.

More information

Map 1.1 is titled, Early Hominins and displays four hominin groups concentrated in Africa. First, Australopithecines are sited near the source of the Nile River west of the Red Sea, near Lake Turkana, in the Olduvai Gorge east of Lake Victoria, and in two places north of the Orange River in southernmost Africa. The ones near Lake Turkana were Australopithecines anamensis and the one north of the Orange River was the Tuang Child. Second, the Earliest human relatives are sited northeast of Lake Chad in central Africa and were Sahelanthropus tchadensis, near the source of the Nile River west of the Red Sea and were Ardipithecus ramidus, and east of Lake Victoria and were Orrorin tugenensis. Homo habilis is sited in the Olduvai Gorge and named Dear Boy. Homo Naledi is sited south of the Limpopo River in southernmost Africa, and Homo sapiens are sited at Jebel Irhoud on Africa’s northwest coast. The map also locates Hadar also called Lucy in the area west of the southern end of the Red Sea.

MAP 1.1 | Early Hominins

The earliest hominin species evolved in Africa millions of years ago.

- Judging from this map, in which parts of Africa has evidence for hominin species been excavated?

- Use Table 1.2 to assign dates to these hominin finds. What, if any, hypotheses might you suggest to correlate the geographic spread of the finds with the evolution of hominin species over time?

- According to this chapter, how did the changing environment of eastern and southern Africa shape the evolution of these modern human ancestors?

Early hominins lived in this manner for more than 4 million years, changing their way of life very little except for moving around the African landmass in their never-ending search for more favorable environments. Even so, their survival is surprising. There were not many of them, and they struggled in hostile environments surrounded by a diversity of large mammals, including predators such as lions.

As the environment changed over the millennia, these early hominins changed as well. Over this 4-million-year period, their brains more than doubled in size; their foreheads became more elongated; their jaws became less massive; and they began to look much more like modern humans. Adaptation to environmental changes also created new skills and aptitudes, which expanded the ability to store and analyze information. With larger brains, hominins could form mental maps of their worlds—they could learn, remember what they learned, and convey these lessons to their neighbors and offspring. In this fashion, larger groups of hominins created communities with shared understandings of their environments.

DIVERSITY Recent discoveries in Kenya, Chad, and Ethiopia suggest that hominins were both older and more diverse than early australopithecine finds (both afarensis and africanus) had suggested. In southern Kenya in 2000, researchers excavated bone remains, at least 6 million years old, of a chimpanzee-sized hominid (named Orrorin tugenensis) that walked upright on two feet. In Chad in 2001, another team unearthed the 7-million-year-old “Toumai skull,” with a mix of attributes (small cranial capacity like a chimp’s but more human-like teeth and spinal column placement at the base of the skull) that perplexed researchers but led them to place this new find, technically named Sahelanthropus tchadensis, in the story of human evolution. These finds indicate that bipedalism must be millions of years older than scientists thought based on discoveries like Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis) and Taung child (Australopithecus africanus). Moreover, Orrorin and Sahelanthropus teeth indicate that they were closer to modern humans than to australopithecines. In their arms and hands, though, which show characteristics needed for tree climbing, the Orrorin hominins seemed more ape-like than the australopithecines. So Orrorin hominins were still somewhat tied to an environment in the trees. Recent analysis has linked the skull fragments of Sahelanthropus with other bones, including ulnae (forearm bones) and a partial femur (thigh bone) found nearby. This evidence together has convinced many paleoanthropologists that Sahelanthropus was both bipedal and comfortable moving through trees.

The story of hominin evolution continues to unfold and demonstrates that hominin diversity continued to thrive in Africa even as other hominins, like Homo erectus, migrated out of the continent. Far inside a cave near Johannesburg, South Africa, spelunkers recently made a discovery that led to the excavation of more than 1,550 fossil remains (now named Homo naledi, for the cave in which they were found). Researchers have been able to assemble a composite skeleton that revealed that the upper body parts resembled some of the much earlier pre-Homo finds, while the hands (both the palms and curved fingers), the wrists, the long legs, and the feet were similar to those of modern humans. The males were around 5 feet tall and weighed 100 pounds, while the females were shorter and lighter. Recent publications have suggested a surprisingly late date range of 335,000 to 236,000 years ago, and therefore much research remains to be done to determine how these fossils fit the story of human evolution.

The fact that different kinds of early hominins were living in isolated societies and evolving separately, though in close proximity to one another, in eastern Africa between 4 and 3 million years ago until as recently as 300,000 years ago indicates much greater diversity among their populations than scholars previously imagined. The environment in eastern Africa generated a fair number of different hominin populations, a few of which would provide our genetic base, but most of which would not survive in the long run.

More information

An archeologist examining footprints imprinted on the ground in Laetoli, Tanzania.

TOOL USE BY HOMO HABILIS One million years after Lucy, the first beings whom we assign to the genus Homo, or “true human,” appeared. Like early hominins, Homo habilis was bipedal, possessing a smooth walk based on upright posture. Homo habilis had an even more important advantage over other hominins: brains that were growing larger. Big brains are the site of innovation: learning and storing lessons so that humans could pass those lessons on to later generations, especially in the making of tools and the efficient use of resources (and, we suspect, in defending themselves). Mary and Louis Leakey, who made astonishing fossil discoveries in the 1950s at Olduvai Gorge in present-day northern Tanzania, identified these important traits. Most notably, the Leakeys found an intact skull that was 1.8 million years old. They nicknamed the find Dear Boy because the discovery meant so much to them and their research into hominins.

Objects discovered with Dear Boy demonstrated that by this time early humans had begun to make tools for butchering animals and, possibly, for hunting and killing smaller animals. The tools were flaked stones with sharpened edges for cutting apart animal flesh and scooping out the marrow from bones. To mimic the slicing teeth of lions, leopards, and other carnivores, these early humans had devised these tools through careful chipping. Dear Boy and his companions had carried usable rocks to distant places, where they made their implements with special hammer stones—tools to make tools. Unlike other tool-using animals (for example, chimpanzees), early humans were now intentionally fashioning implements, not simply finding them when needed. More important, they were passing on knowledge of these tools to their offspring and, in the process, gradually improving the tools. The Leakeys, believing that making and using tools represented a new stage in the evolution of human beings, gave Dear Boy and his companions the name Homo habilis, or “skillful human.” While scholars today may debate whether toolmaking (rather than walking upright or having a large brain) is the key trait that distinguishes the first humans from earlier hominins, Homo habilis’s skills made them the forerunners, though very distant ones, of modern men and women.

More information

Olduvai Gorge with the Naibor Soit hills in the distance and a large monolith made of the red sediments in the foreground. The Gorge is a desert landscape sparsely populated with brush.

Migrations of Homo erectus

By 1 million years ago, many of the hominin species that flourished together in Africa had died out. One surviving species, which emerged about 1.8 million years ago, had a large brain capacity and walked truly upright; it therefore gained the name Homo erectus, or “standing human.” Three important features distinguished Homo erectus from their competitors and made them more able to cope with environmental changes: their family dynamics, use of fire, and ability to travel long distances. Discoveries in Asia and Europe show that Homo erectus migrated out of Africa in some of the earliest waves of hominin migration around the globe.

FAMILY DYNAMICS One of the traits that contributed to the survival of Homo erectus was the development of extended periods of caring for their young. Although their enlarged brain gave these hominins advantages over the rest of the animal world, it also brought one significant problem: their heads were too large to pass through the females’ pelvises at birth. Their pelvises were only big enough to deliver an infant with a cranial capacity that was about a third an adult’s size. As a result, offspring required a long period of protection by adults as they matured and their brain size tripled.

This difference from other species also affected family dynamics. For example, the long maturation process gave adult members of hunting and gathering bands time to train their children in those activities. In addition, maturation and brain growth required mothers to spend years breast-feeding and then preparing food for children after their weaning. In order to share the responsibilities of child-rearing, mothers relied on other women (their own mothers, sisters, and friends) and girls (often their own daughters) to help with nurturing and protecting, a process known as allomothering (literally, “other mothering”).

USE OF FIRE Homo erectus began to make rudimentary attempts to control their environment by means of fire. It is hard to tell from fossils when hominins—Homo erectus or Homo sapiens (modern humans)—learned to use fire. While the earliest fire use was essentially fire foraging (taking advantage of naturally occurring fires, such as from lightning strikes), hearths for intentional fire cultivation date back as far as 800,000 years ago. Less conservative estimates suggest that hominin mastery of fire occurred nearly 1.5 million years ago. Fire provided heat, protection, a gathering point for small communities, and a way to cook food. It was also symbolically powerful: here was a source of energy that humans could extinguish and revive at will. The uses of fire had enormous long-term effects on human evolution. Because they were able to boil, steam, and fry wild plants, as well as otherwise undigestible foods (especially raw muscle fiber), hominins who mastered this technology could expand their diets. Because cooked foods yield more energy than raw foods and because the brain, while only 2 percent of human body weight, uses between 20 and 25 percent of all the energy that humans take in, cooking was decisive in the evolution of brain size and functioning.

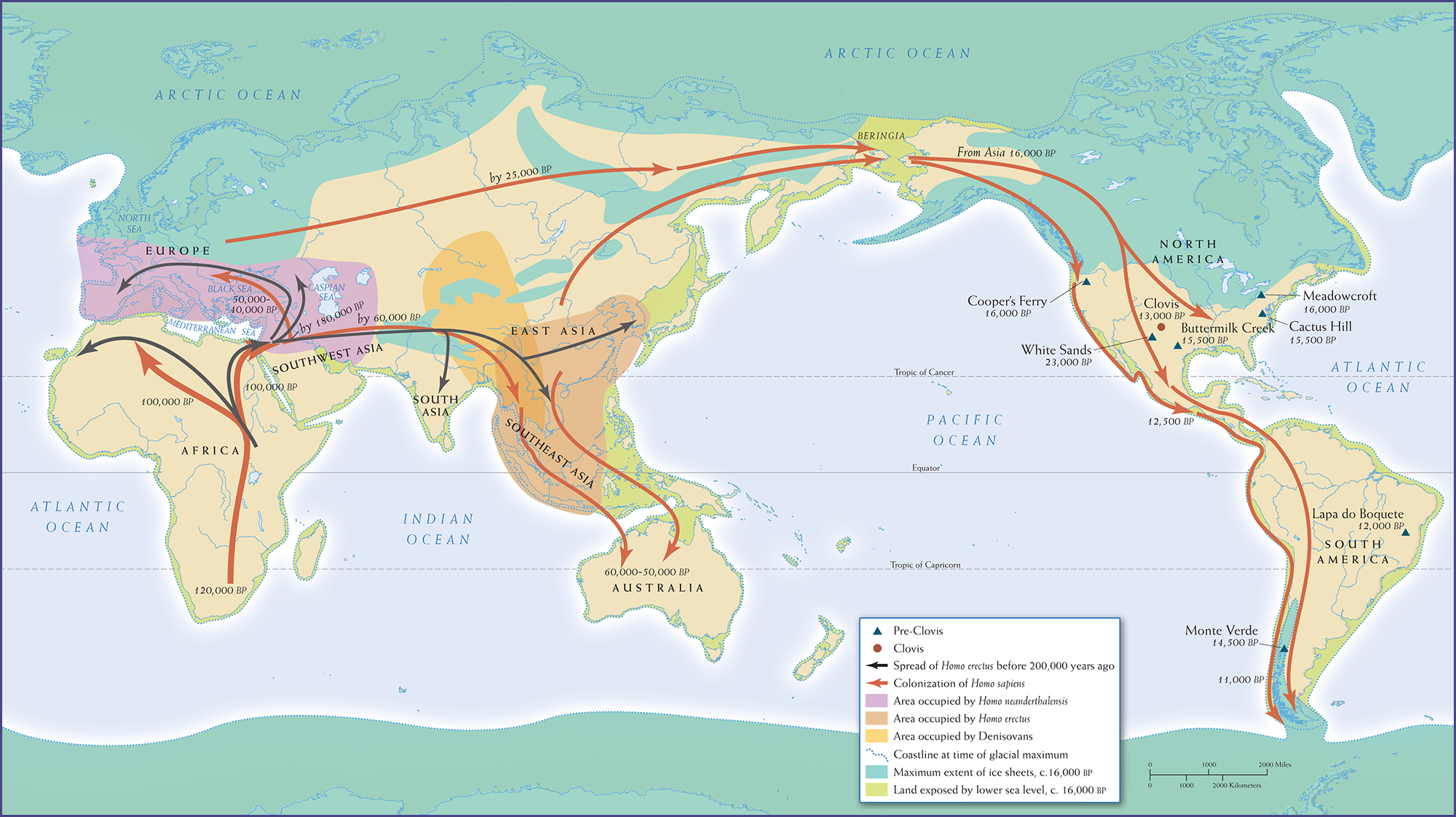

EARLY MIGRATIONS Being bipedal, Homo erectus could move with a smooth and rapid gait, so they could cover large distances quickly. They were the world’s first long-distance travelers, forming the first mobile human communities. (See Table 1.2.) Around 1.5 million years ago, Homo erectus individuals began migrating out of Africa, first into the lands of Southwest Asia. From there, they traveled along the Indian Ocean shoreline, moving into South Asia and Southeast Asia and later northward into what is now China. Their migration was a response in part to the environmental changes that were transforming the world. The Northern Hemisphere experienced thirty major cold phases during this period, marked by glaciers spreading over vast expanses of the northern parts of Eurasia and the Americas. The glaciers formed as a result of intense cold that froze much of the world’s oceans, lowering them some 325 feet below present-day levels. These lower ocean levels made it possible for the migrants to travel across land bridges into Southeast Asia and from East Asia to Japan, as well as from New Guinea to Australia. The last parts of the Afro-Eurasian landmass to be occupied were in Europe.

Discoveries of the bone remains of “Java Man” and “Peking Man” (named according to the places where archaeologists first unearthed their remains) confirmed early settlements of Homo erectus in Southeast and East Asia. The remains of Java Man, found in 1891 on the island of Java, turned out to be those of an early Homo erectus that had dispersed into Asia nearly 2 million years ago. Peking Man, found near Beijing in the 1920s, was a cave dweller, toolmaker, and hunter and gatherer who settled in northern China. Originally believing that Peking Man dated to around 400,000 years ago, archaeologists thought that a warmer climate might have made the region more hospitable to migrating Homo erectus. But recent application of the aluminum-beryllium technique to analyze the fossils has suggested they date to 770,000 years ago, a time when China’s climate would have been much colder. Peking Man’s brain was larger than that of his Javan cousins, and there is evidence that he controlled fire and cooked meat in addition to hunting large animals. He made tools of vein quartz, quartz crystals, flint, and sandstone. A major innovation was the double-faced axe, a stone instrument whittled down to sharp edges on both sides to serve as a hand axe, a cleaver, a pick, and probably a weapon to hurl against foes or animals. Even so, these early predecessors still lacked the intelligence, language skills, and ability to create culture that would distinguish the first modern humans from their hominin relatives.

|

TABLE 1.2 | Migrations of Homo sapiens |

|

|

SPECIES |

TIME |

|

Homo erectus leave Africa |

c. 1.5 MYA |

|

Homo sapiens leave Africa |

c. 180,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Homo sapiens migrate into Asia |

c. 120,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Homo sapiens migrate into Australia |

c. 60,000 YEARS AGO |

| Homo sapiens migrate into Europe |

c. 50,000 YEARS AGO |

| Homo sapiens migrate into the Americas |

c. 23,000 YEARS AGO |

More information

An illustration of the globe with numerous lines representing ancestor-descendant relationships. In Africa most of the lines are contained within the continent, but there are some connecting to Europe and Asia. Most of the lines in Africa represent lineages going back 10,000 to 50,000 generations ago, with some more recent lineages going back 100 to 10,000 generations present as well. In Europe and Asia most of the lines are contained within the Eurasian landscape, but there are some lines stretching to Africa and across the Pacific ocean. Most of the lineages go back 100 to 10,000 generations, with the highest concentration of lineages going back about 1000 generations.

CORE OBJECTIVES

COMPARE the narrative of human evolution to the creation narratives covered earlier.

Homo sapiens: The First Modern Humans

The first traces that we have of Homo sapiens come from present-day Morocco and suggest that the first modern humans emerged sometime around 315,000 years ago. This bigger-brained, more dexterous, and more agile species of humans differed from their precursors, including Homo habilis and Homo erectus. Their distinctive traits, including greater cognitive skills, made Homo sapiens the first modern humans and enabled them to spread out from Africa by 100,000 years ago and flourish in even more diverse regions across the globe than Homo erectus did.

Large-scale shifts in Africa’s climate and environment several hundred thousand years ago put huge pressures on all types of mammals, including hominins. In these extremely warm and dry environments, the smaller, quicker, and more adaptable mammals survived. What counted now was no longer large size and brute strength, but the ability to respond quickly, with agility, and with great speed. The eclipse of Homo erectus by Homo sapiens was not inevitable. After all, Homo erectus was already scattered around Africa and Eurasia by the time Homo sapiens emerged; in contrast, even as late as 100,000 years ago there were only about 10,000 Homo sapiens adults living primarily in a small part of the African landmass. When Homo sapiens began moving in large numbers out of Africa and the two species encountered each other in the same places across the globe, Homo sapiens individuals were better suited to survive—in part because of their greater cognitive and language skills.

More information

An illustration of the hipbone and femur of three different humanoid species.The first figure is an illustration of Lucy, the second figure is an illustration of a Orrorin tugenensis, and the third figure is an illustration of a Homo sapien. Each figure has the image of its hipbone and femur superimposed on one of its legs.

The Homo sapiens newcomers followed the trails blazed by earlier migrants when they moved out of Africa. (See Map 1.2.) Evidence, including part of a fossilized jaw with teeth, from a cave on Mount Carmel in Israel indicates that Homo sapiens were living there as early as 180,000 years ago. Whether that evidence suggests significant migrations or more limited forays by Homo sapiens is still unclear. Nevertheless, it is clear that from 120,000 to 50,000 years ago, Homo sapiens were moving in ever increasing numbers into the same areas as their genetic cousins, reaching across Southwest Asia and from there into central Asia—but not into Europe. They flourished and reproduced. By 30,000 years ago, the population of Homo sapiens had grown to about 300,000. Between 60,000 and 12,000 years ago, these modern humans were surging into areas tens of thousands of miles from the Rift Valley and the Ethiopian highlands of Africa.

In the area of present-day China, Homo sapiens were thriving and creating distinct regional cultures. Consider Shandingdong Man, a Homo sapiens who dates to about 18,000 years ago. His physical characteristics were closer to those of modern humans, and he had a similar brain size. His stone tools, which included choppers and scrapers for preparing food, were similar to those of the Homo erectus Peking Man. His bone needles, however, were the first stitching tools of their kind found in China, and they indicated the making of garments. Some of the needles measured a little over an inch in length and had small holes drilled in them. Shandingdong Man also buried his dead. In fact, a tomb of grave goods includes ornaments suggesting the development of aesthetic tastes and religious beliefs.

Homo sapiens were also migrating into the northeastern fringe of East Asia. In the frigid climate there, they learned to follow herds of large Siberian grazing animals. The bones and dung of mastodons made decent fuel and good building material. Pursuing their prey eastward as the large-tusked herds sought pastures in the steppes (treeless grasslands) and marshes, these groups migrated across the ice to Japan. Archaeologists have discovered a woolly mammoth fossil in the colder north of Japan, for example, and an elephant fossil in the warmer south. Elephants in particular roamed the warmer parts of Inner Eurasia. The hunters and gatherers who moved into Japan gathered wild plants for sustenance, and they dried, smoked, or broiled meat by using fire.

About 30,000 years ago, Homo sapiens began edging into the weedy landmass that linked Siberia and North America (which hominins had not populated). This thousand-mile-long land bridge, later called Beringia, must have seemed like an extension of familiar steppe-land terrain, and these individuals lived isolated lives there on a broad and (at the time) warm plain for thousands of years before beginning to migrate into North America. Until recently, it was thought that the first migrations occurred around 16,000 years ago, by foot and by boat. Recent analysis of botanical evidence at a site in White Sands, New Mexico, has confirmed a set of human footprints that date as far back as 23,000 years ago. Once humans started migrating to the Americas, they poured eastward and southward into North America. A final migration occurred about 8,000 years ago by boat, since by then the land bridge had disappeared under the sea. (See Map 1.2 for evidence that demonstrates the complex picture of the peopling of the Americas, both along the western coastline and to the east.)

|

TABLE 1.3 | Human Evolution |

|

|

SPECIES |

TIME* |

|

Sahelanthropus tchadensis (including Toumai skull) |

7 MYA |

|

Orrorin tugenensis |

6 MYA |

|

Ardipithecus ramidus |

4.4 MYA |

|

Australopithecus anamensis |

4.2 MYA |

|

Australopithecus afarensis (including Lucy) |

3.9 MYA |

|

Australopithecus africanus (including Taung child) |

3.0 MYA |

|

Homo habilis (including Dear Boy) |

2.5 MYA |

|

Homo erectus and Homo ergaster (including Java and Peking Man) |

1.8 MYA |

|

Homo heidelbergensis (common ancestor of Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens) |

600,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Homo neanderthalensis |

c. 400,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Denisovans (no agreement yet on taxonomic name, but in genus Homo) |

c. 400,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Homo sapiens |

300,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Homo naledi |

c. 280,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Homo sapiens sapiens (modern humans) |

35,000 YEARS AGO |

|

*Dates are approximate (midpoint on a range), based on multiple finds. Some species are represented with hundreds of examples (more than 300 examples of Australopithecus afarensis, of which “Lucy” is the most famous, date across a span of almost 1 million years), while the evidence for other species is more limited. The still much-debated Sahelanthropus tchadensis is represented by a single find of a skull and possibly femur and two forearm bones. The physical evidence for the Denisovans is a jaw from China and a pinky-bone and teeth from a cave in Siberia. |

|

|

Source: Smithsonian Institute Human Origins Program. |

|

Using their cognitive abilities to adapt to new environments and to innovate, these migrants, who were the first discoverers of America, began to fill up the landmasses. They found ample prey in the herds of woolly mammoths, caribou, 3-ton giant sloths, and 200-pound beavers. But the explorers could also themselves be prey—for they encountered saber-toothed tigers, long-legged eagles, and giant bears that moved faster than horses. The melting of the glaciers about 8,000 years ago and the resulting disappearance of the land bridge eventually cut off the first Americans from their Afro-Eurasian origins. Thereafter, the Americas became a world apart from Afro-Eurasia.

Although modern humans evolved from earlier hominins, no straight-line descent tree exists from the first hominins to Homo sapiens. Increasingly, scientists view our origins as shaped by a series of progressions and regressions as hominin species adapted or failed to adapt and died out. The remains of now-extinct hominin species, such as Homo ergaster, Homo heidelbergensis, Homo neanderthalensis, and now Homo naledi (see Table 1.3), offer intriguing glimpses of ultimately unsuccessful branches of the complex human evolutionary tree. Spreading into Europe and parts of Southwest Asia along with other hominins, Neanderthals, for example, had big brains, used tools, wore clothes, buried their dead, hunted, lived in rock shelters, and even interacted with Homo sapiens. Yet when faced with environmental challenges, Homo sapiens survived, while Neanderthals died out sometime between 45,000 and 35,000 years ago, although recent genetic evidence suggests that some interbreeding occurred between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens.

More information

Map 1.2 is entitled Early Migrations: Out of Africa. The world map shows Pre-Clovis sites; Clovis sites; the spread of Homo erectus before 200,000 years ago; the colonization of Homo sapiens; the area occupied by Homo neanderthalensis; the area occupied by Homo erectus; the coastline at the time of glacial maximum; the maximum extent of ice sheets circa 16,000 B P; and land exposed by lower sea level circa 16,000 B P. Pre-Clovis sites are located in the area of northwestern United States (14,000 B P); at Buttermilk Creek in the area of Texas (15,500 B P); at Cactus Hill in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States (15,500 B P); at Meadowcroft near the Eastern Great Lakes (16,000 B P), at Lapa do Boquete in the mid-Eastern coastal section of Brazil (12,000 B P); and at Monte Verde in Chile (14,500 B P). Clovis site is located in the area of New Mexico (13,000 B P). The spread of Homo erectus before 200,000 years ago starts in the area of east-central Africa and splits, with one route going to Africa’s northwest coast and the other to the area of Egypt and into the Middle East (by 180,000 B P). From there two routes head north into eastern Europe and then western Europe, and another route heads east through Southwest Asia and then into South Asia (India), and East Asia. The colonization of Homo sapiens starts in southern Africa (120,000 B P) and follows much of the routes just described for the spread of Homo erectus, reaching the areas of northwest and northeast Africa by 100,000 B P, the area of eastern Europe by 50,000 to 40,000 BP, and Southwest Asia by 60,000 BP. Routes continued through Southeast Asia to Australia (60,000 to 50,000 B P). A route from northern Europe by 25,000 B P went across northern Asia to Beringia (from Asia 16,000 BP) and then down the coast and into the central area of North America (12,5000 B P) and to the tip of South America (11,000 B P). The area occupied by Homo neanderthalensis covers western Europe south of Scandinavia to Spain, central Europe including the Black Sea area, and the western Asia area around the Caspian Sea. The area occupied by Homo erectus is the southern portion of East Asia as well as Southeast Asia. The coastline at the time of glacial maximum extends beyond the present-day coastline on all continents. The maximum extent of ice sheets circa 16,000 B P includes the Arctic Ocean and the northern half of North America and Europe, as well as isolated sections of South and Central Asia, Beringia, and a large area north of Antarctica. The land exposed by lower sea level circa 16,000 B P includes all of Beringia and those areas of other continents between the coastline and the time of global maximum and the present-day coastline.

Indeed, several species could exist simultaneously, but some were more suited to changing environmental conditions—and thus more likely to survive—than others. Evidence that interbreeding between these different species may have given some Homo sapiens a survival advantage emerged in 2008, when Russian archaeologists dug up a pinky bone at the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia and thereby discovered another hominin group that had many of the characteristics of Homo sapiens. These hominins, who looked different from Homo sapiens, had lived in this cave off and on from 287,000 years ago. They even shared a common ancestor with the Neanderthals about 400,000 years ago and interbred with the Neanderthals and our own species, as indicated by DNA drawn from living peoples in East Asia, Australia, the Pacific Islands, and the Americas. Some scientists have suggested that the interbreeding of Homo sapiens with the Denisovans enabled modern humans to survive in the Tibetan highlands at altitudes of close to 11,000 feet and as early as 15,000 years ago. Using aDNA drawn from Denisovan remains, scientists have reconstructed their body types, noting that they had massive brain cases and giant molars as well as larger neck vertebrae, thicker ribs, and a higher bone density than modern humans. They may have weighed well over 200 pounds and were robust and very large individuals. Scholars’ understanding of this recent hominin relative, genetically distinct from Neanderthals and modern humans, is only beginning to take form. For instance, 5 percent of the DNA of modern humans of Papua New Guinean descent is Denisovan and likely contributes to their immune response to various diseases.

Although the primary examples emphasized in this chapter—Homo habilis and Homo erectus—were among some of the world’s first human-like inhabitants, they probably were not direct ancestors of modern men and women. By 25,000 years ago, DNA analysis reveals, nearly all genetic cousins to Homo sapiens had become extinct. Homo sapiens, with their physical agility and superior cognitive skills, were ready to populate the world.

Glossary

- hominids

- The family, in scientific classification, that includes gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans (that is, Homo sapiens, in addition to our now-extinct hominin ancestors such as the various australopithecines as well as Homo habilis, Homo erectus, and Homo neanderthalensis).

- hominins

- A scientific classification for modern humans and our now-extinct ancestors, including australopithecines and others in the genus Homo, such as Homo habilis and Homo erectus. Researchers once used the term hominid to refer to Homo sapiens and extinct hominin species, but the meaning of hominid has been expanded to include great apes (humans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans).

- evolution

- Process by which species of plants and animals change over time, as a result of the favoring, through reproduction, of certain traits that are useful in that species’ environment.

- australopithecines

- Hominin species, including anamensis, afarensis (Lucy), and africanus, that appeared in Africa beginning around 4 million years ago and, unlike other animals, sometimes walked on two legs. Their brain capacity was a little less than one-third of a modern human’s. Although not humans, they carried the genetic and biological material out of which modern humans would later emerge.

- Homo habilis

- Species, confined to Africa, that emerged about 2.5 million years ago and whose toolmaking ability truly made it the forerunner, though a very distant one, of modern humans. Homo habilis means “skillful human.”

- Homo erectus

- Species that emerged about 1.8 million years ago, had a large brain, walked truly upright, migrated out of Africa, and likely mastered fire. Homo erectus means “standing human.”

- Homo sapiens

- The first humans; emerged in Africa as early as 315,000 years ago and migrated out of Africa beginning about 180,000 years ago. They had bigger brains and greater dexterity than previous hominin species, whom they eventually eclipsed.