Global Agricultural Revolution

Global Agricultural Revolution

About 12,000 years ago (around 10,000 BCE), a fundamental shift occurred in the way humans produced food for themselves—what some scholars have called an agricultural, or ecological, revolution. Around the same time, a significant warming trend that had begun around 11,000 BCE resulted in a profusion of plants and animals, large numbers of which began to exist closer to humans. In this era of major change, humans established greater control over nature. The transformation consisted of the domestication of wild plants and animals. Population pressure was one factor that triggered the move to settled agriculture, as hunting and gathering alone could not sustain the growth in numbers of people. A revolution in agriculture, in turn, led to a vast population expansion because men and women could now produce more calories per unit of land. As various plants and animals were domesticated around the world, people settled in villages and social relationships changed.

The Beginnings of Settled Agriculture and Pastoralism

Learning to control environments through the domestication of plants and animals was a gradual process. Communities shifted from a hunting and gathering lifestyle (which requires moving around in search of food) to one based on agriculture (which requires staying in one place until the soil has been exhausted). Settled agriculture refers to the application of human labor and tools to a fixed plot of land for more than one growing cycle. Alternatively, some people adopted a lifestyle based on pastoralism (the herding of domesticated animals), which complemented settled farming.

More information

A wall painting of people herding cattle. There are many small human figures interacting with each other. The humans are walking behind the group of cattle and pushing them in one direction.

EARLY DOMESTICATION OF PLANTS AND ANIMALS The formation of settled communities enabled humans to take advantage of favorable regions and to take risks, spurring agricultural innovation. In areas with abundant wild game and edible plants, people began to observe and experiment with the most adaptable plants. For ages, people gathered grains by collecting seeds that fell freely from their stalks. At some point, observant collectors perceived that they could obtain larger harvests if they pulled grain seeds directly from plants. The process of plant domestication probably began when people noticed that certain edible plants retained their nutritious grains longer than others, so they collected these seeds and scattered them across fertile soils. When ripe, these plants produced bigger and more concentrated crops. Plant domestication occurred when the plant retained its ripe, mature seeds, allowing an easy harvest. People used most seeds for food but saved some for planting in the next growing cycle, to ensure a food supply for the next year.

Dogs were the first animals to be domesticated (although in fact they may have adopted humans, rather than the other way around). At least 33,000 years ago in China and central Asia, including Mongolia and Nepal, humans first domesticated gray wolves and made them an essential part of human society. Dogs did more than comfort humans. They provided an example of how to achieve the domestication of other animals and, with their herding instincts, they helped humans control other domesticated animals, such as sheep. In the central Zagros Mountains region, where wild sheep and wild goats were abundant, they became the next animal domesticates. Perhaps hunters returned home with young wild sheep, which then reproduced, and their offspring never returned to the wild. The animals accepted their dependence because the humans fed them. Since controlling animal reproduction was more reliable than hunting, domesticated herds became the primary source of protein in the early humans’ diet.

When the number of animals under human control and living close to the settlement outstripped the supply of food needed to feed them, community members could move the animals to grassy steppes for grazing. These pastoralists herded domesticated animals, moving them to new pastures on a seasonal basis. Goats, the other main domesticated animal of Southwest Asia, are smarter than sheep but more difficult to control. The pastoralists may have introduced goats into herds of sheep to better control herd movement. Pigs and cattle also came under human control at this time.

TRANSHUMANT HERDERS AND NOMADIC PASTORALISTS Pastoralism appeared as a way of life around 5500 BCE, essentially at the same time that full-time farmers appeared (although the beginnings of plant and animal domestication had begun many millennia earlier). Over time, two different types of pastoralists with different relationships to settled populations developed: transhumant herders and nomadic pastoralists. Transhumant herders were closely affiliated with agricultural villages whose inhabitants grew grains, especially wheat and barley, which required large parcels of land. These herders produced both meat and dairy products, as well as wool for textiles, and exchanged these products with the agriculturalists for grain, pottery, and other staples. Extended families might farm and herd at the same time, growing crops on large estates and grazing their herds in the foothills and mountains nearby. They moved their livestock seasonally, pasturing their flocks in higher lands during summer and in valleys in winter. This movement over short distances is called transhumance and did not require herders to vacate their primary living locations, which were generally in the mountain valleys.

In contrast with transhumant pastoralism, nomadic pastoralism came to flourish especially in the steppe lands north of the agricultural zone of southern Eurasia. This way of life was characterized by horse-riding herders of cattle and other livestock. Because horses provided decisive advantages in transportation and warfare, they gained more value than other domesticated animals. Thus, horses soon became the measure of household wealth and prestige. Unlike the transhumant herders, the nomadic pastoralists often had no fixed home, though they often returned to their traditional locations. They moved across large distances in response to the size and needs of their herds. Beginning in the second millennium BCE the northern areas of the Eurasian landmass, stretching from present-day Ukraine across Siberia and Mongolia to the Pacific Ocean, became the preserve of these horse-riding pastoral peoples, living as they did in a region unable to support the extensive agriculture necessary for large settled populations.

Historians know much less about these horse-riding pastoral nomads than about the agriculturalists and the transhumant herders, as their numbers were small and they left fewer archaeological traces or historical records. Their role in world history, however, is as important as that of the settled societies. In Afro-Eurasia, they domesticated horses and developed weapons and techniques that at certain points in history enabled them to conquer sedentary societies. As we will see in the next section (and later chapters), they also transmitted ideas, products, and people across long distances, maintaining the linkages that connected east and west.

CORE OBJECTIVES

COMPARE the ways communities around the world shifted to settled agriculture.

Agricultural Innovation: Afro-Eurasia and the Americas

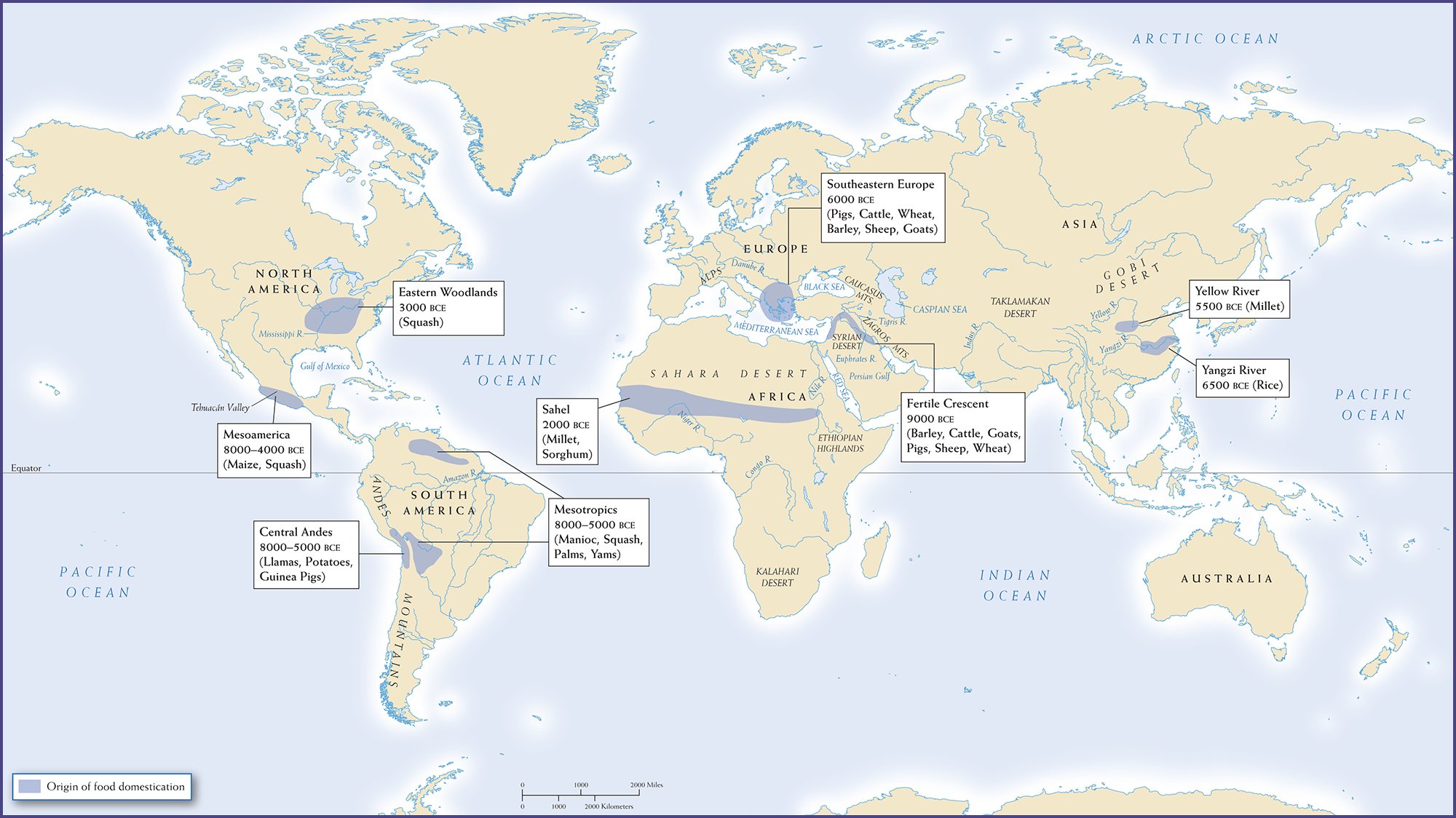

The agricultural revolutions that occurred worldwide between 9000 and 2000 BCE had much in common: climatic change; increased knowledge about plants and animals; and the need for more efficient ways to feed, house, and promote the growth of a larger population. These concerns led peoples in Eurasia, the Americas, and Africa to see the advantages of cultivating plants and domesticating wildlife. (See Map 1.4.).

Some communities were independent innovators, developing agricultural techniques based on their specific environments. In Southwest Asia, East Asia, Africa, and the Americas, the distinctive crops and animals that humans first domesticated reflect independent innovation. As we will see in the following section, other communities (such as those in Europe) were borrowers of ideas, which spread through migration and contact with other regions. In all of these populations, the shift to settled agriculture was revolutionary.

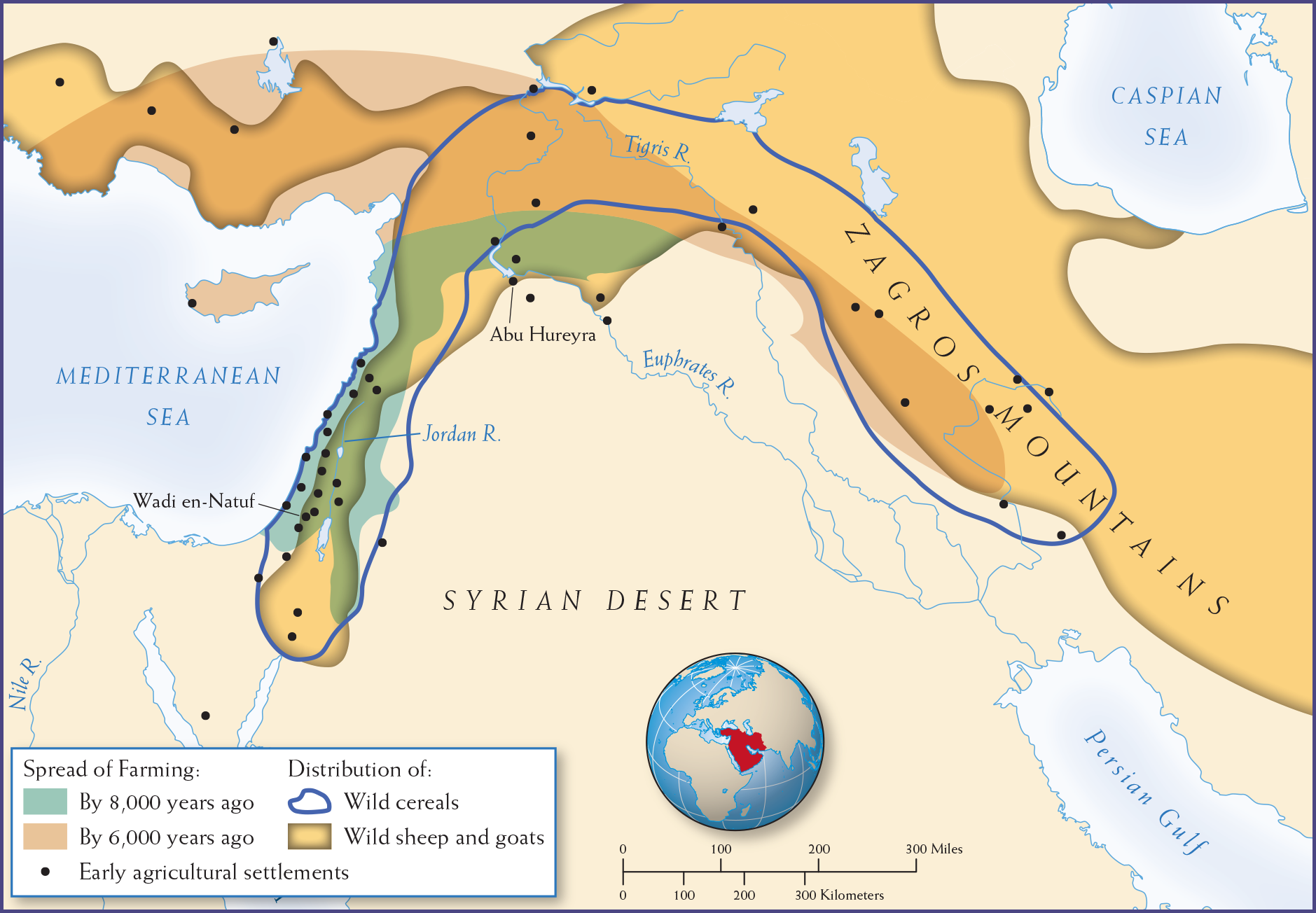

SOUTHWEST ASIA: CEREALS AND MAMMALS The first agricultural revolution occurred in Southwest Asia in an area bounded by the Mediterranean Sea and the Zagros Mountains, a region known today as the Fertile Crescent because of its rich soils and regular rainfall. (See Map 1.5.) Around 9000 BCE, in the southern corridor of the Jordan River valley, humans began to domesticate the wild ancestors of barley and wheat, which were the easiest to adapt to settled agriculture and the easiest to transport. Although the changeover from gathering wild cereals to regular cultivation took several centuries and saw failures as well as successes, by 8000 BCE cultivators were selecting and storing seeds and then sowing them in prepared seedbeds. Moreover, in the valleys of the Zagros Mountains on the eastern side of the Fertile Crescent, similar experimentation was occurring with animals around the same time. Of the six large mammals—goats, sheep, pigs, cattle, camels, and horses—that have been vital for meat, milk, skins, and transportation, humans in Southwest Asia domesticated all except horses. With the presence of so many valuable plants and animals, Southwest Asia led the agricultural revolution and gave rise to many of the world’s first major city-states (see Chapter 2).

More information

Map 1.4 is titled, “The Origins of Food Production and Animal Domestication.” Domestication of pigs, cattle, sheep, and goats first emerged in the Fertile Crescent in 8000 B C E, as did the cultivation of wheat and barley, all of these moving to Southeastern Europe in 6000 B C E, while llamas and guinea pigs were domesticated during those periods in the Central Andes. Millet is cultivated along the Yellow River in China from 5500 B C E, and rice along the Yangzhi River from 6500 B C E. Sorghum and millet were grown in the Sahel region of Africa beginning in 2000 B C E. Squash was cultivated in the Eastern Woodlands area of North America starting in 3000 B C E, while Maize and Squash emerged in Mesoamerica in Central America from 8000-4000 B C E. The Mesotropics regions of South America saw the cultivation of manioc, squash, palms, and yams emerge from 8000-5000 B C E, while the Central Andes region witnessed the domestication of llama and guinea pigs, as well as the cultivation of potatoes, beginning in 8000-5000 B C E.

MAP 1.4 | The Origins of Food Production and Animal Domestication

Agricultural production emerged in many regions at different times. The variety of patterns reflected local resources and conditions.

- In how many different locations, and at what different times, did agricultural production and animal domestication emerge? What is the range of crops and animals domesticated in each region?

- What specific geographic features (for instance, specific mountains, rivers, or latitudes) are common among these early food-producing areas? Do those geographic features appear to guarantee agricultural production?

- Why do you think agriculture emerged in certain areas and not in others?

More information

Map 1.5 is titled, “The Birth of Farming in the Fertile Crescent.” The map shows the spread of farming by 8,000 years ago, and then by 6,000 years ago, as well as the location of early agricultural settlements and the distribution of both wild cereals and wild sheep and goats. By 8,000 years ago, farming spread to a narrow band running east from the area around the Jordan River to the Fertile Crescent region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. By 6,000 years ago it spreads further north and west into Turkey and well as south and east to the edge of the Zagros Mountains. Early agricultural settlements are clustered in the area around the Jordan (including Wadi-en-Natuf) as well as along the nearby coast of the Mediterranean Sea and the Fertile Crescent (including Abu Hureyra). The distribution of wild cereals follows a slightly larger but similar distribution to that of agriculture 6,000 years ago (though it does not extend into Turkey), while wild sheep and goats are distributed in a much larger range that extends into western Turkey as well as throughout the Zagros Mountains and both south towards the Persian Gulf and east to the edge of the Caspian Sea.

MAP 1.5 | The Birth of Farming in the Fertile Crescent

Agricultural production occurred in the Fertile Crescent starting roughly between 11,000–9000 BCE. Though the process was slow, farmers and herders domesticated a variety of plants and animals, which led to the rise of large-scale, permanent settlements.

- Trace the region where the wild cereals were domesticated as well as the density of agricultural settlements. How does the region you traced relate to the reason this area is called the “Fertile Crescent”?

- What topographical features appear to influence the location of agricultural settlements and farming?

- What relationship existed between cereal cultivators and herders of goats and sheep?

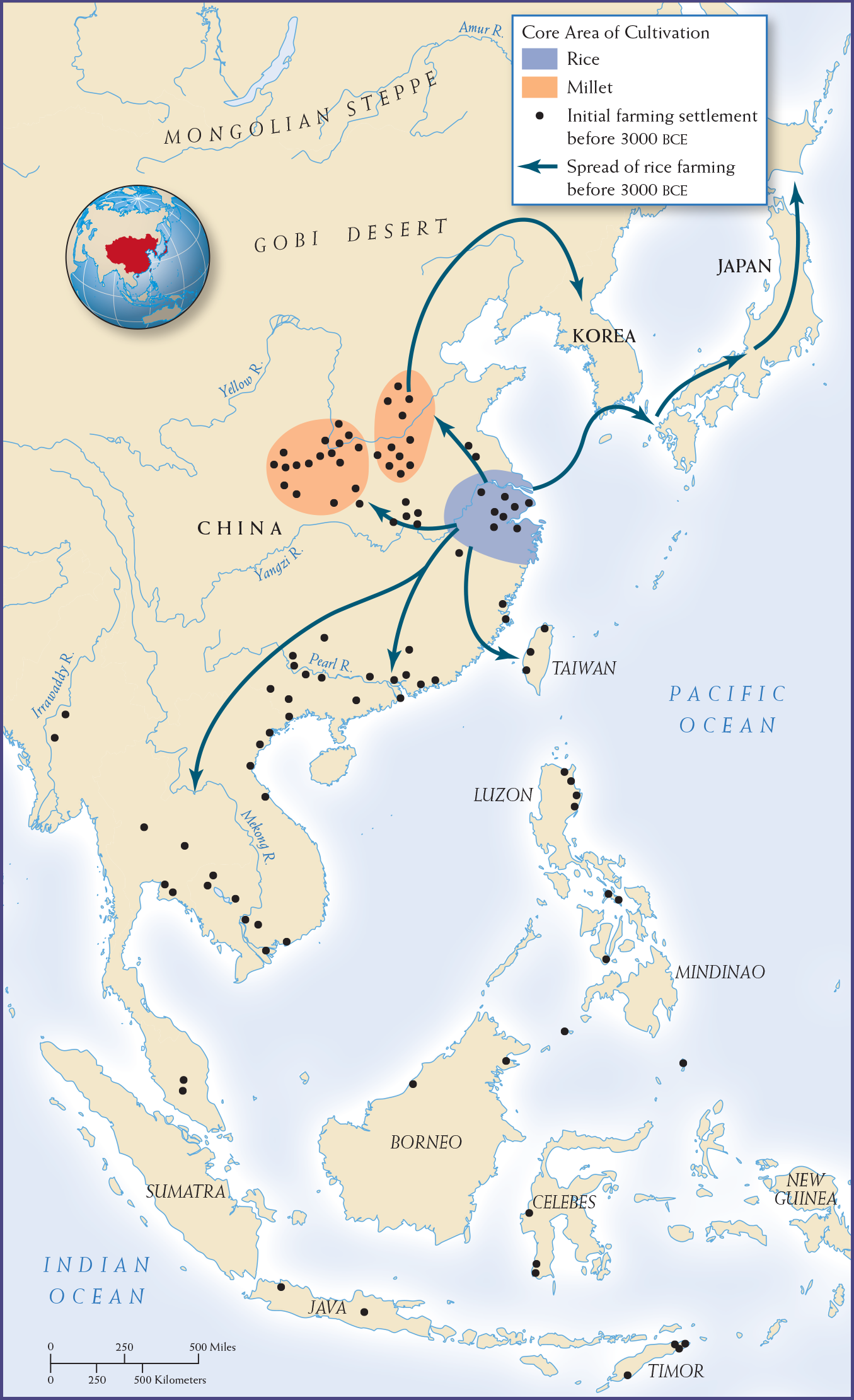

EAST ASIA: WATER AND RICE A revolution in food production also occurred among the coastal dwellers in East Asia, although under different circumstances. (See Map 1.6.) As the rising sea level created the Japanese islands, hunters in that area tracked a diminishing supply of large animals, such as giant deer. When big game became extinct, men and women sought other ways to support themselves, and before long they settled down and became cultivators of the soil. In this postglacial period, divergent human cultures flourished in northern and southern Japan. Hunters in the south created primitive pebble and flake tools, whereas those in the north used sharper blades about a third of an inch wide. Production of earthenware pottery—a breakthrough that enabled people to store food more easily—also may have begun in this period in the south. Throughout the rest of East Asia, the spread of lakes, marshes, and rivers created habitats for population concentrations and agricultural cultivation. Two newly formed river basins, along the Yellow River in northern China and the Yangzi River in central China, became densely populated areas that were focal points for intensive agricultural development.

More information

Map 1.6 is titled, “The Spread of Farming in East Asia.” Two core areas of millet cultivation are shown, both along China’s Yellow River, while the one core rice area is along the easternmost area of the Yangzi River where it meets the Pacific Ocean. Both those core areas have large numbers of initial farming settlements; farming settlements also exist in southern China by the Pearl River, as well as Southeast Asia in the areas of Vietnam and Cambodia, as well as the Indonesian islands and the Philippines. The map shows that rice farming spread from its core area north, east to Korea and Japan, as well as northwest to the core areas of millet cultivation, southeast to Taiwan, and further south, and west into southern China and Vietnam.

MAP 1.6 | The Spread of Farming in East Asia

Agricultural settlements appeared in East Asia between 6500 and 5500 BCE, several thousand years later than they did in the Fertile Crescent.

- According to this map, where did early agricultural settlements appear in East Asia?

- What two main crops were domesticated in East Asia? Where did each crop type originate, and to what regions did each spread?

- How did the physical features of these regions shape agricultural production?

More information

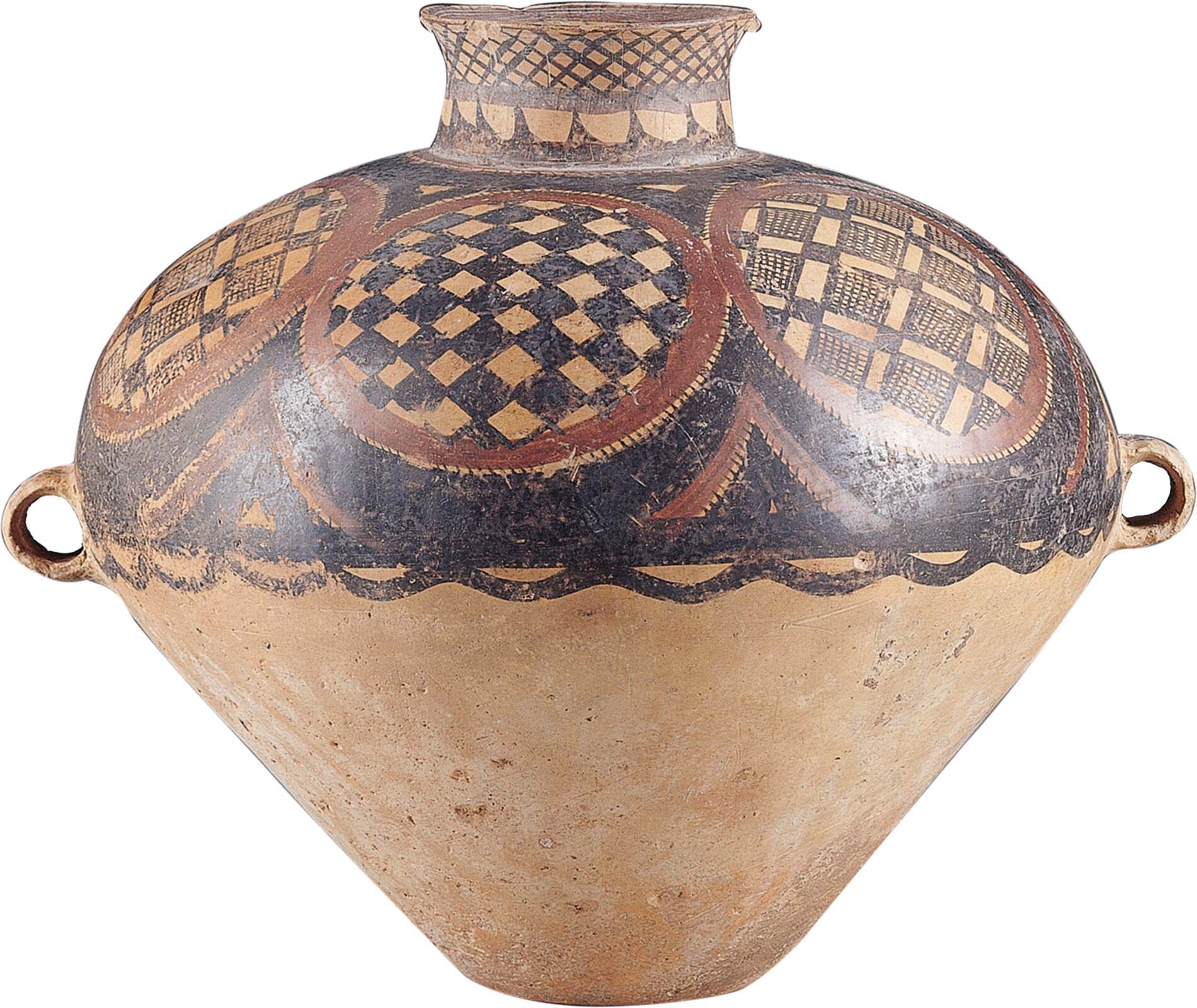

A large Yangshao pot with a wide mid-section and two small handles on either side. The top half is decorated with geometric designs in black and red.

What barley and wheat were for Southwest Asia, rice along the Yangzi River and millet along the Yellow River were for East Asia: staples adapted to local environments that humans could domesticate to support a large, sedentary population. Archaeologists have found evidence of rice cultivation in the Yangzi River valley in 6500 BCE, and of millet cultivation in the Yellow River valley in 5500 BCE. Innovations in grain production, including the introduction of a faster-ripening rice from Southeast Asia, spread through internal migration and wider contacts. Ox plows and water buffalo plowshares were prerequisites for large-scale millet planting in the drier north and the rice-cultivated areas of the wetter south. By domesticating plants and animals, the East Asians, like the Southwest Asians, laid the foundations for more populous societies.

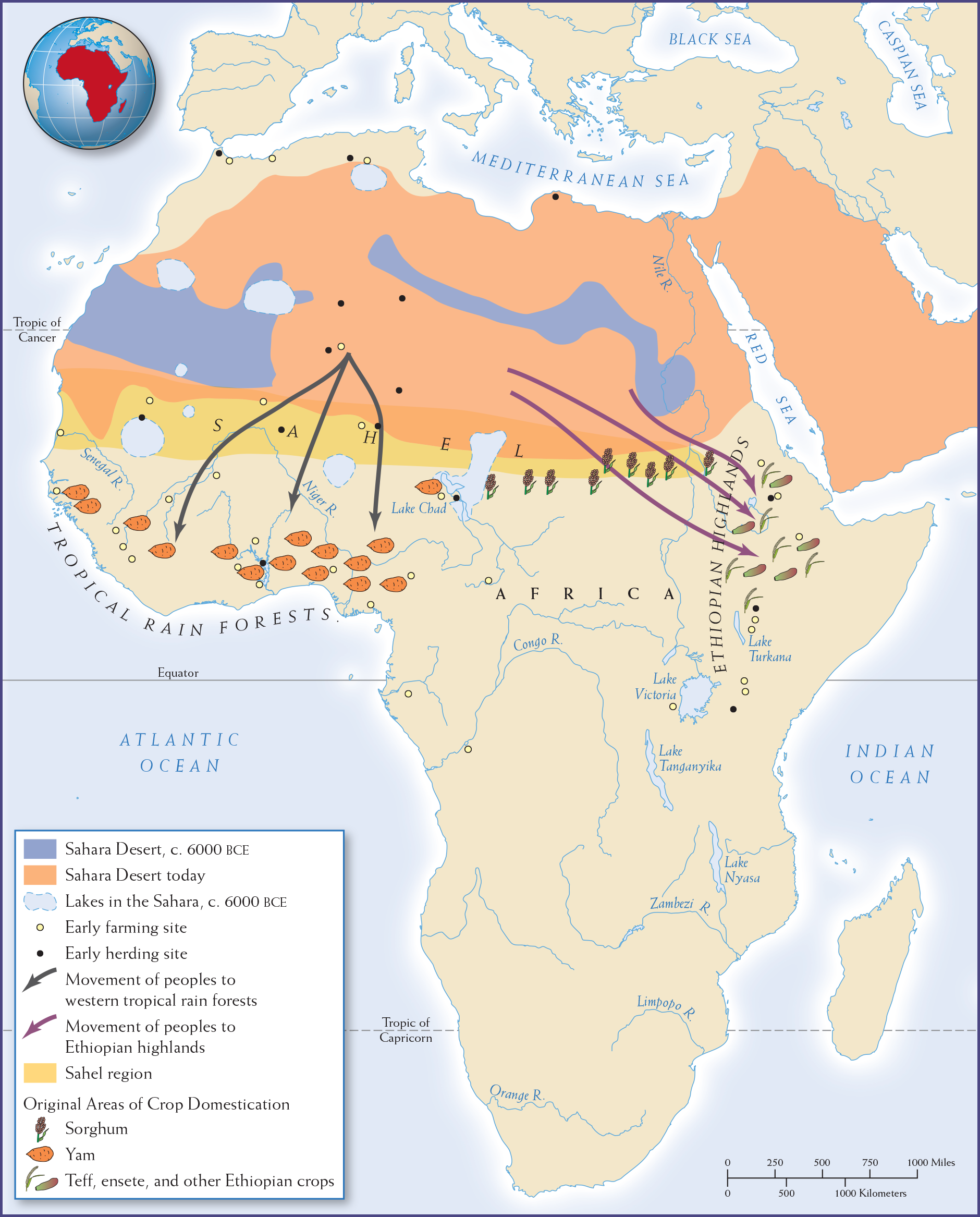

AFRICA: THE RACE WITH THE SAHARA The evidence for settled agriculture in the various regions of Africa is less clear. Most scholars think that the Sahel area (spanning the African landmass just south of the Sahara Desert) was likely where hunters and gatherers became settled farmers and herders without borrowing from other regions. In this area, an apparent move to settled agriculture, including the domestication of large herd animals, occurred two millennia before it did along the Mediterranean coast in North Africa. From this innovative heartland, Africans carried their agricultural breakthroughs across the landmass.

In the wetter and more temperate locations of the vast Sahel, particularly in mountainous areas and their foothills, villages and towns developed. These regions were lush with grassland vegetation and teeming with animals. Before long, the inhabitants had made sorghum, a cereal grass, their principal food crop. Residents constructed stone dwellings, underground wells, and grain storage areas. In one such population center, fourteen circular houses faced each other to form a main thoroughfare, or a street.

The Sahel was colder and moister in 8000 BCE than it is today. As the world became warmer and the Sahara Desert expanded, around 2000 BCE, this region’s inhabitants had to disperse and take their agricultural and herding skills into other parts of Africa. (See Map 1.7.) Some went south to the tropical rain forests of West Africa, while others trekked eastward into the Ethiopian highlands. In their new environments, farmers searched for new crops to domesticate. The rain forests of West Africa yielded root crops, particularly the yam and cocoyam, both of which became the principal life-sustaining foodstuffs. The ensete plant, similar to the banana, played the same role in the Ethiopian highlands. Thus, the beginnings of agriculture in Africa involved both innovation and diffusion, as Africans applied the techniques that first emerged in the Sahel to new plants and animals.

More information

Map 1.7 is titled, “The Spread of Farming in Africa.” The map shows how societies living in the Sahel (the region south of the Sahara Desert that stretches between the West African coasts by the Senegal River all the way to the Ethiopian Highlands) developed their own version of agricultural production after 6000 B C E. It shows the extent of the Sahara circa 6000 B C E (only two sections, one in West Africa along the Tropic of Cancer, the other a thin strip stretching east to the Nile River), as well as a number of former lakes clustered in North and West Africa that have since dried up. This contrasts with the much larger Sahara today, which covers almost all of Africa above the Sahel, as well as Saudi Arabia. Early farming sites, most either in the western Sahel or south towards the Equator and the tropical rainforests of West Africa, are also shown, as well as herding sites further north in the area of Africa that was not desert circa 6000 but has become so today. The map also shows the movement of peoples south through the Sahel and to the tropical rainforests of West Africa where yams were originally domesticated. It also shows the movement of peoples from the edge of the eastern part of the former Sahara desert across those areas of the Sahel where sorghum is originally domesticated and into the Ethiopian Highlands where teff, ensete, and other Ethiopian crops are originally domesticated.

MAP 1.7 | The Spread of Farming in Africa

Societies living in the Sahel (the region south of the Sahara Desert) developed their own version of agricultural production after 6000 BCE.

- Why is the Sahel so important in the movement of peoples and ideas about crops?

- Why did farming spread in the directions that it did?

- What do you note about the location of farming and herding sites?

- How did the expansion of the Sahara Desert affect the diffusion of agriculture in the Sahel?

THE AMERICAS: A SLOWER TRANSITION TO AGRICULTURE The shift to settled agriculture occurred more slowly in the Americas. When people entered the Americas around 23,000 years ago (21,000 BCE), they set off an ecological transformation but also adapted to unfamiliar habitats. The flora and fauna of the Americas were different enough to induce the early settlers to devise ways of living that distinguished them from their ancestors in Afro-Eurasia. Then, when the glaciers began to melt around 12,500 BCE and water began to cover the land bridge between East Asia and America, the Americas and their peoples truly became a world apart.

Food-producing changes in the Americas were different from those in Afro-Eurasia because the Americas did not undergo the sudden cluster of innovations that revolutionized agriculture in Southwest Asia and elsewhere. Tools ground from stone, rather than chipped implements, appeared in the Tehuacán Valley in present-day eastern central Mexico by 6700 BCE, and evidence of plant domestication there dates back to 5000 BCE. But villages, pottery making, and sustained population growth came later. For many early American inhabitants, the life of hunting, trapping, and fishing went on as it had for millennia.

On the coast of what is now Peru, people found food by fishing and by gathering shellfish from the Pacific. Archaeological remains include the remnants of fishnets, bags, baskets, and textile implements; gourds for carrying water; stone knives, choppers, and scrapers; and bone awls (long, pointed spikes often used for piercing) and thorn needles. Thousands of villages likely dotted the seashores and riverbanks of the Americas. Some communities made breakthroughs in the management of fire, which enabled them to manufacture pottery; others devised irrigation and water sluices in floodplains; and some even began to send their fish catches inland in return for agricultural produce.

Maize (corn), squash, and beans (first found in what is now central Mexico) became dietary staples. The early settlers foraged small seeds of maize, peeled them from ears only a few inches long, and planted them. Maize offered real advantages because it was easy to store, relatively imperishable, nutritious, and easy to cultivate alongside other plants. Nonetheless, it took 5,000 years for farmers to complete its domestication. Over the years, farmers had to mix and breed different strains of maize for the crop to evolve from thin spikes of seeds to cobs rich with kernels, with a single plant yielding big, thick ears to feed a growing permanent population. Thus, the agricultural changes afoot in Mesoamerica were slow and late in maturing. The pace was even more gradual in South America, where early settlers clung to their hunting and gathering traditions.

Across the Americas, the settled, agrarian communities found that legumes (beans), grains (maize), and tubers (potatoes) complemented one another in keeping the soil fertile and offering a balanced diet. Unlike the Afro-Eurasians, however, the settlers did not use domesticated animals as an alternative source of protein. In only a few pockets of the Andean highlands is there evidence of the domestication of tiny guinea pigs, which may have been tasty but unfulfilling meals. Nor did people in the Americas tame animals that could protect villages (as dogs did in Afro-Eurasia) or carry heavy loads over long distances (as cattle and horses did in Afro-Eurasia). Although llamas could haul heavy loads, they were uncooperative and only partially domesticated, and thus mainly useful only for their fur, which was used for clothing.

Nonetheless, the domestication of plants and animals in the Americas, as well as the presence of villages and clans, suggests significant diversification and refinement of technique. At the same time, the centers of such activity were many, scattered, and more isolated than those in Afro-Eurasia—and thus more narrowly adapted to local geographical climatic conditions, with little exchange between communities. This fragmentation in migration and communication was a distinguishing force in the gradual pace of change in the Americas, and it contributed to their taking a path of development separate from Afro-Eurasia’s.

Borrowing Agricultural Ideas: Europe

In some places, agricultural revolution occurred through the borrowing of ideas from neighboring regions, rather than through innovation. Peoples living at the western fringe of Afro-Eurasia, in Europe, learned the techniques of settled agriculture through contact with other regions. By 7000 BCE, people in parts of Europe close to the societies of Southwest Asia, such as Greece and the Balkans, were abandoning their hunting and gathering way of life for an agricultural one. The Franchthi Cave in Greece, for instance, reveals that around 6000 BCE the inhabitants learned how to domesticate animals and plant wheat and barley, having borrowed that innovation from their neighbors in Southwest Asia.

The emergence of agriculture and village life occurred in Europe along two separate paths of borrowing. (See Map 1.8.) The first and most rapid trajectory followed the northern rim of the Mediterranean Sea: from what is now Turkey through the islands of the Aegean Sea to mainland Greece, and from there to southern and central Italy and Sicily. Whether the process involved the actual migration of individuals or, rather, the spread of ideas, connections by sea quickened the pace of the transition. Within a relatively short period of time, hunting and gathering gave way to domesticated agriculture and herding.

The second trajectory of borrowing took an overland route: from Anatolia, across northern Greece into the Balkans, then northwestward along the Danube River into the Hungarian plain, and from there farther north and west into the Rhine River valley in modern-day Germany. This route of agricultural development was slower than the Mediterranean route for two reasons. First, domesticated crops, or individuals who knew about them, had to travel by land, as there were few large rivers like the Danube. Second, it was necessary to find new groups of domesticated plants and animals that could flourish in the colder and more forested lands of central Europe, which meant planting crops in the spring and harvesting them in the autumn, rather than the other way around. Cattle rather than sheep became the dominant herd animals.

In Europe, the main cereal crops were wheat and barley (additional plants such as olives came later), and the main herd animals were sheep, goats, and cattle—all of which had been domesticated in Southwest Asia. Hunting, gathering, and fishing still supplemented the new settled agriculture and the herding of domesticated animals.

More information

Map 1.8 is titled, “The Spread of Farming in Europe.” The map shows how farming communities spread across Europe between 7000 and 4500 B C E, as well the location of early farming communities, regions of dense hunter-gatherer settlements to 4500 B C E, and the two routes of agricultural diffusion through Europe, continental and coastal. Sections of the map show the spread of farming communities through Southeastern Europe, including Greece, Bulgaria, and Romania (7000-5500 B C E); Mediterranean Europe, including the Adriatic coast, Italy and the southern coasts of France and Spain (7000-4500 B C E); and Central Europe, including Germany, Poland, and northern France (5500-4500 B C E). Early farming communities are concentrated throughout these three areas, while regions of dense hunter-gatherer settlements appear on the northern coasts of Spain and France, southern England (connected to France via a land bridge), the Scandinavian coasts that touch the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, as well as the banks of the Dneiper River. The coastal route of agricultural diffusion moves west from Cyprus and Turkey along the Greek coast, to and around Sicily, north along the Italian coast, and then west and south along the coasts of France and Spain. The continental route of agricultural diffusion moves west from Turkey into Greece and the Balkans, then northwest along the Danube into the Hungarian plain, and from there into the Rhine River valley and then France along the Seine and Loire Rivers.

MAP 1.8 | The Spread of Agriculture in Europe

The spread of agricultural production into Europe after 7000 BCE represents geographic diffusion. Europeans borrowed agricultural techniques and technology from other groups, adapting those innovations to their own situations.

- Trace the two pathways by which agriculture spread across Europe. What shaped the routes by which agriculture diffused?

- How might scholars know that there were two routes of diffusion, and why would the existence of different diffusion routes matter?

- Identify the locations of the early farming communities. What geographical features seem to have influenced where these farming communities sprang up?

Thus, across Afro-Eurasia and the Americas, humans changed and were changed by their environments. While herding and gathering remained firmly entrenched as a way of life, certain areas with favorable climates and plants and animals that could be domesticated began to establish settled agricultural communities, which were able to support larger populations than hunting and gathering could sustain.

CORE OBJECTIVES

ANALYZE the significance the shift to settled agriculture had for social organization across global regions.

Revolutions in Social Organization

In addition to creating agricultural villages, the domestication of plants and animals brought changes in social organization, notably changes in gender relationships.

LIFE IN VILLAGES In the many regions across the globe where domestication of plants and animals took hold, agricultural villages were established near fields for accessible sowing and cultivating, and near pastures for herding livestock. Villagers collaborated to clear fields, plant crops, and celebrate rituals in which they sang, danced, and sacrificed to nature and the spirit world for fertility, rain, and successful harvests. They also produced stone tools to work the fields, and clay and stone pots or woven baskets to collect and store the crops. The earliest dwelling places of the first settled communities were simple structures: circular pits with stones piled on top to form walls, with a cover stretched above that rested on poles. Social structures were equally simple, being clan-like and based on kinship networks. With time, however, population growth enabled clans to expand. As the use of natural resources intensified, specialized tasks evolved and divisions of labor arose. Some community members procured and prepared food; others built terraces and defended the settlement. Later, residents built walls with stones or mud bricks and clamped them together with wooden fittings. Some villagers became craftworkers, devoting their time to producing pottery, baskets, textiles, or tools, which they could trade to farmers and pastoralists for food. Craft specialization and the buildup of surpluses contributed to social stratification (the emergence of distinct and hierarchically arranged social classes), as some people accumulated more land and wealth while others led the rituals and sacrifices.

More information

An artist’s drawing of the settlement at Çatal Hüyük shows several one-room houses arranged in a dense honeycomb design. The houses are white, rise to different heights, and face in different directions. Several roofs have been removed from the drawing to show the belongings inside.

Archaeological sites in Southwest Asia have provided evidence of what life was like in some of the earliest villages. At Wadi en-Natuf, for example, located about 10 miles from present-day Jerusalem, a group of people known historically as Natufians began to dig sunken pit shelters and to chip stone tools around 12,500 BCE. In the highlands of eastern Anatolia, large settlements clustered around monumental public buildings with impressive stone carvings that reflect a complex social organization. In central Anatolia around 7500 BCE, at the site of Çatal Hüyük, a dense honeycomb settlement featured rooms with artwork of a high quality. The walls were covered with paintings, and sculptures of wild bulls, hunters, and pregnant women enlivened many rooms.

As people moved into the river valley in Mesopotamia (in present-day Iraq) along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, small villages began to appear after 5500 BCE. They collaborated to build simple irrigation systems to water their fields. Perhaps because of the increased demands for community work to maintain the irrigation systems, the communities in southern Mesopotamia became stratified, with some people having more power than others. We can see from the burial sites and myriad public buildings uncovered by archaeologists that, for the first time, some people had higher status derived from birth rather than from the merits of their work. A class of people who had access to more luxury goods, and who lived in bigger and better houses, now became part of the social organization.

MEN, WOMEN, AND EVOLVING GENDER RELATIONS Gender roles became more pronounced during the gradual transition to agriculturally based ways of life. For millions of years, biological differences—the fact that females give birth to offspring and lactate to nourish them, and that males do neither of these—determined female and male behaviors and attitudes toward each other. One can speak of the emergence of gender relations and roles, which are socially and culturally constructed, as distinct from biological differences only with the appearance of modern humans (Homo sapiens). Only when humans began to think in complex symbolic ways and give voice to these perceptions in a spoken language did well-defined gender categories of man and woman crystallize.

As human communities became larger, more hierarchical, and more powerful, the rough gender egalitarianism of hunting and gathering societies eroded. Because women had been the primary gatherers, their knowledge of wild plants had contributed to early settled agriculture, but they did not necessarily benefit from that transition. Advances in agrarian tools introduced a harsh working life that undermined women’s earlier status as farmers. Men, no longer so involved in hunting and gathering, now took on the heavy work of yoking animals to plows. Women took on the backbreaking and repetitive tasks of planting, weeding, harvesting, and grinding the grain into flour. Thus, although agricultural innovations increased productivity, they also increased the drudgery of work, especially for women. Fossil evidence from Abu Hureyra, Syria, reveals damage to the vertebrae, osteoarthritis in the toes, and curved and arched femurs, all suggesting that the work of bending over and kneeling in the fields took its toll on female agriculturalists. The increasing differentiation of the roles of men and women also affected power relations within households and communities. The senior male figure became dominant in these households, and males dominated females in leadership positions.

The agricultural revolution marked a greater division among men, as well as between men and women. Where the agricultural transformation was most widespread, and where population densities began to grow, the social and political differences created inequalities. As these inequalities affected gender relations, patriarchy (the rule of senior males within households) began to spread around the globe.

Glossary

- domestication

- Bringing a wild animal or plant under human control.

- settled agriculture

- Humans’ use of tools, animals, and their own labor to work the same plot of land for more than one growing cycle. It involves switching from a hunting and gathering lifestyle to one based on farming.

- pastoralism

- A way of life in which humans herd domesticated animals and exploit their products (hides/fur, meat, and milk). Pastoralists include nomadic groups that range across vast distances, as well as transhumant herders who migrate seasonally in a more limited range.