THE BIG PICTURE

Identify the earliest river-basin societies. What are their shared characteristics?

THE BIG PICTURE

Identify the earliest river-basin societies. What are their shared characteristics?

The First Cities

Around 3500 BCE, cultural changes, population growth, and technological innovations gave rise to complex societies. Clustered in cities, these larger communities developed new institutions, and individuals took on a wide range of social roles and occupations, resulting in new hierarchies based on wealth and gender. At the same time, the number of small villages and pastoralist communities grew.

Water was the key to settlement, since predictable flows of water determined where humans settled. Reliable water supplies allowed communities to sow crops adequate to feed large populations. Abundant rainfall allowed the world’s first villages to emerge, but the breakthroughs into big cities occurred in drier zones where large rivers formed beds of rich soils deposited by flooding rivers. With irrigation innovations, soils became arable. Equally important, a worldwide warming cycle expanded growing seasons. The river basins—with their fertile soil, irrigation, and available domesticated plants and animals—made possible the agricultural surpluses needed to support city dwellers.

The Earliest Civilizations

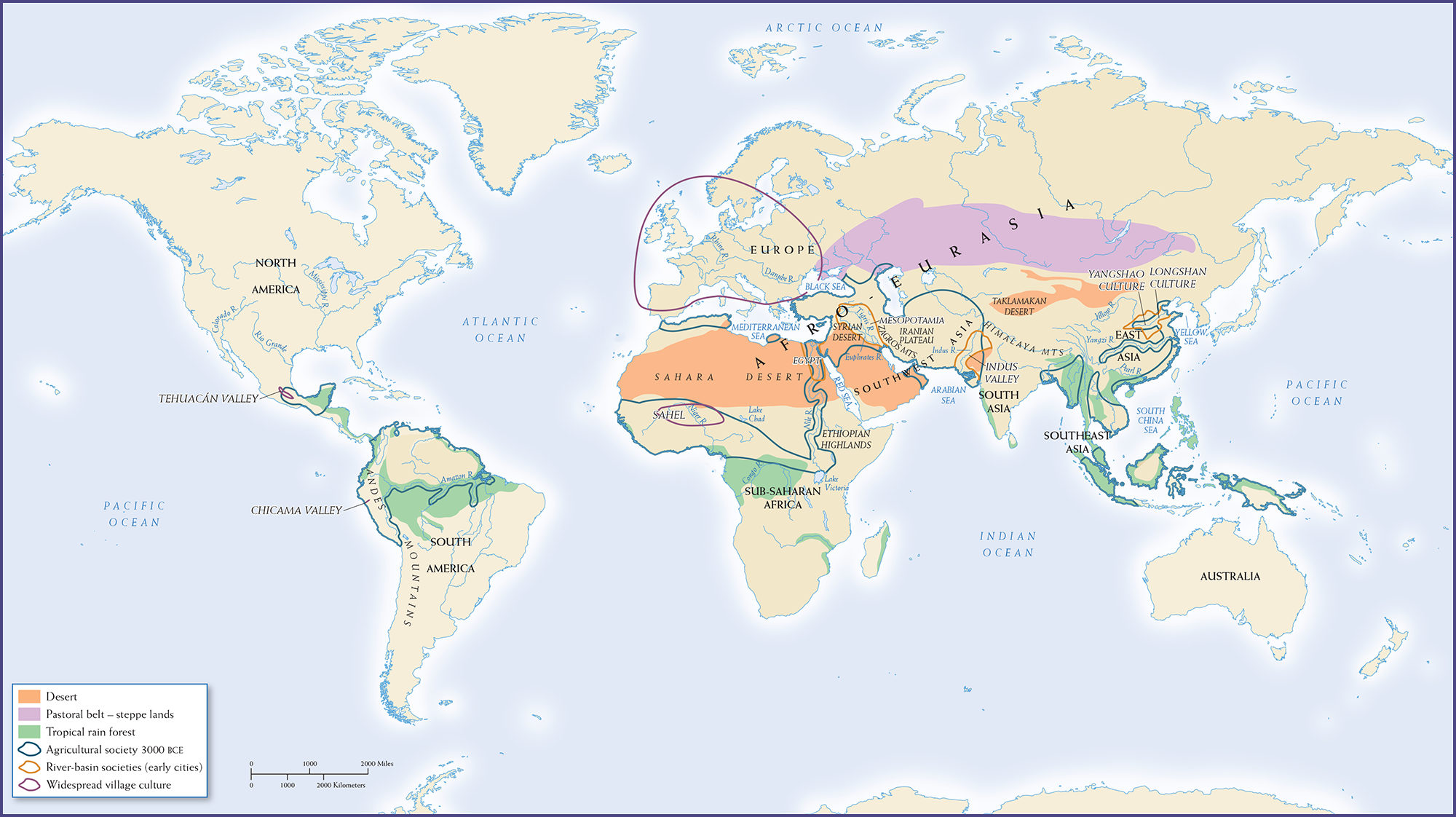

The material and social advances of the early cities occurred in a remarkably short period—from 3500 to 2000 BCE—in three locations: the basin of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in central Southwest Asia; the northern parts of the Nile River flowing toward the Mediterranean Sea; and the Indus River basin in northwestern South Asia. About a millennium later, a similar process began along the Yellow River and the Yangzi River in China. (See Map 2.1.) In these regions humans farmed and fed themselves by relying on intensive irrigation agriculture. Gathering in cities inhabited by rulers, administrators, priests, and craftworkers, they changed their methods of organizing communities by worshipping new gods in new ways and by obeying divinely inspired monarchs and elaborate bureaucracies. New technologies appeared, ranging from the wheel for pottery production to metalworking and stoneworking for the creation of both luxury objects and utilitarian tools. The technology of writing used the storage of words and meanings to extend human communication and memory.

Map 2.1 is titled, “The World in the Third Millennium B C E.” The extent of three different climate zones (desert, pastoral belt-steppe lands, and tropical rain forest) during this period, as well as the location of the agricultural society in 3000 B C E, river-basin societies (early cities), and widespread village culture, are marked on the map. Desert covers most of northern Africa, as well as Saudi Arabia, Syria, Taklamakan north of the Himalaya Mountains in central Asia, and a section of the Indus Valley. Pastoral belt-steppe lands cover a wide swath of Central Asia, running east from the Black Sea to China. Tropical rain forest covers most of Southeast Asia, the western portion of Sub-Saharan Africa, and the eastern coast of Central America as well as the area around the Amazon River in South America. Europe, the Tehuacan Valley in Central America, and the Sahel around the Niger River are the location of widespread village culture. In 3000 B C E, agricultural society extends across the northern portion of South and Central America; the area between the Sahara desert and Sub-Saharan Africa, including the Nile down to the Ethiopian Highlands; and much of Southeast and East Asia. River basin societies are located in China (Yangshao and Longshan Culture), the Indus Valley, Egypt, and the Fertile Crescent around the Tigris River.

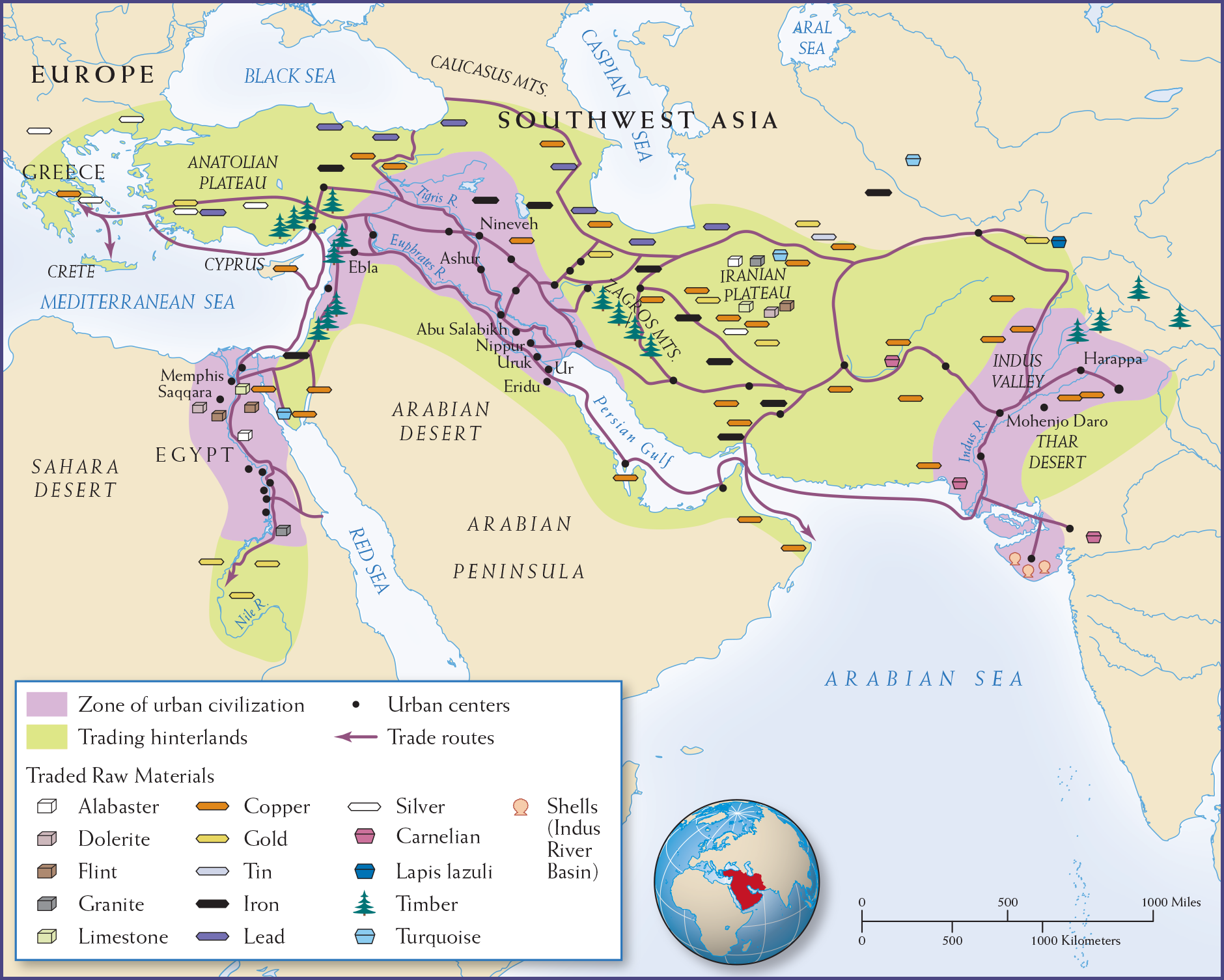

With cities and new technologies came greater divisions of labor. Dense urban settlement enabled people to specialize in making goods for the consumption of others: weavers made textiles, potters made ceramics, and jewelers made precious ornaments. Soon these goods were traded with outlying areas. As trade expanded over longer distances, raw materials such as wool, metal, timber, and precious stones arrived in the cities and could be fashioned into new, manufactured goods. (See Map 2.2.) One of the most coveted metals was copper: easily smelted and shaped (not to mention shiny and alluring), it became the metal of choice for charms, sculptures, and valued commodities. When combined with arsenic or tin, copper hardens and becomes bronze, which is useful for tools and weapons. Consequently, this period marks the beginning of the Bronze Age, even though the use of this alloy extended into and flourished during the second millennium BCE (see Chapter 3).

The dawn of cities and city-states had drawbacks for those who had been hunters and gatherers or had lived in towns. As rulers, scribes, bureaucrats, priests, artisans, and wealthy farmers rose, so did social stratification. Men made gains at the expense of women, for men dominated the prestigious positions and societies became highly patriarchal. All those who lived close to cities had to fashion their own city-states to protect themselves lest they be exploited, or even enslaved.

The emergence of cities as population centers created one of history’s most durable worldwide distinctions: the urban-rural divide. Where cities appeared alongside rivers, people adopted lifestyles based on specialized labor and the mass production of goods. In contrast, most people continued to live in the countryside, where they remained on their lands, cultivating the land or tending livestock, though they exchanged their grains and animal products for goods from the urban centers. The two ways of life were interdependent and both worlds remained linked through family ties, trade, politics, and religion.

The transhumant herder communities that had appeared in Southwest Asia around 5500 BCE (see Chapter 1) continued to be small with impermanent settlements. They lacked substantial public buildings or infrastructure, but their seasonal moves followed a consistent pattern. Across the vast expanse of Afro-Eurasia’s great mountains and its desert barriers, and from its steppe lands ranging across inner and central Eurasia to the Pacific Ocean, these transhumant herders lived alongside settled agrarian people, especially when occupying their lowland pastures. They traded animal products such as meat, hides, and milk for grains, pottery, and tools produced in the agrarian communities.

In the arid environments of Inner Mongolia and central Asia, transhumant herding and agrarian communities initially followed the same combination of herding animals and cultivating crops that had proved so successful in Southwest Asia. However, it was in this steppe environment, unable to support large-scale farming, that some communities began to concentrate exclusively on animal breeding and herding. Though some continued to fish, hunt, and farm small plots in their winter pastures, by the middle of the second millennium BCE many societies had become full-scale pastoral communities.

Map 2.2 is titled, “Trade and Exchange in Southwest Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean, Third Millennium B C E.” The zone of urban civilization is along the Nile River in Egypt, up the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the Levant, along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and along the Indus River and Indus Valley. Urban centers are located along the Nile and include Memphis and Saqqara. The area also includes traded raw materials such as gold, granite, alabaster, flint, limestone, copper, and lapis lazuli. Along the Mediterranean are copper, iron, timber, lead, and gold. Along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers are the cities Elba, Nineveh, Ashur, Abu Salabikh, Nippur, Uruk, Eridu, and Ur. Greece, the Anatolian Plateau, the Iranian Plateau, and the Thar Desert are the trading hinterlands. Greece has copper; the Anatolian plateau has gold, lead, iron, copper, turquoise, and timber. The Iranian plateau has copper, lead, iron, gold, timber, carnelian, limestone, dolerite, flint, alabaster, and lapis lazuli. In the Indus Valley, there are the cities Mohenjo Daro and Harappa and also copper, timber, carnelian, and shells. Multiple trade routes travel through Egypt, Levant, Anatolian Plateau, Greece, Crete, Southwest Asia, the Iranian Plateau, and the Indus Valley.

MAP 2.2 | Trade and Exchange in Southwest Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean, Third Millennium BCE

Extensive commercial networks linked the urban cores of Southwest Asia.

These pastoralists dominated steppe life. The area that these pastoral societies occupied lay between 40 degrees and 55 degrees north and extended the entire length of Eurasia from the Great Hungarian Plain to Manchuria, a distance of 5,600 miles. The steppe itself divided into two zones, an eastern one and a western one, the separation point being the Altai Mountains in Central and East Asia where the modern states of Russia, China, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan come together. Frost-tolerant and drought-resistant plant life predominated in the region. Over time, pastoralist groups—both transhumant herders and pastoral nomads (more on this distinction in Chapter 3)—played a vital role by interacting with cities, connecting more urbanized areas, and spreading ideas throughout Afro-Eurasia.