Monumental Architecture

CORE OBJECTIVES

EXPLAIN the religious, social, and political developments that accompany early urbanization in the river-basin societies from 3500 to 2000 BCE.

Between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers: Mesopotamia

The world’s first complex society arose in Mesopotamia. Here the river and the first cities changed how people lived. Mesopotamia, whose name is a Greek word meaning “[region] between two rivers,” is a landmass including all of modern-day Iraq and parts of Syria and southeastern Turkey. From their headwaters in the mountains to the north and east to their destination in the Persian Gulf, the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers are wild and capricious. Unpredictable floodwaters could wipe out years of hard work, but when managed properly they could transform the landscape into verdant and productive fields. Both rivers provided water for irrigation and, although hardly navigable, were important routes for transportation and communication by pack animal and by foot. Mesopotamia’s natural advantages—its rich agricultural land and water, combined with easy access to neighboring regions—favored the growth of cities and later territorial states (see Chapter 3). These cities and states became the sites of important cultural, political, and social innovations.

More information

A stone carving of a man directing water through an aqueduct.

Tapping the Waters

The first rudimentary advances in irrigation occurred in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains along the banks of the smaller rivers that feed the Tigris. Converting the floodplain—where the river overflows and deposits fertile soil—into a breadbasket required mastering the unpredictable waters. Both the Euphrates and the Tigris, unless controlled by waterworks, were unfavorable to cultivators because the annual floods occurred at the height of the growing season, when crops were most vulnerable. Low water levels occurred when crops required abundant irrigation. To prevent the river from overflowing during its flood stage, farmers built levees along the banks and dug ditches and canals to drain away the floodwaters. Engineers devised an irrigation system whereby the Euphrates, which has a higher riverbed than the Tigris, essentially served as the supply and the Tigris as the drain. Storing and channeling water year after year required constant maintenance and innovation by a corps of engineers.

The Mesopotamians’ technological breakthrough was in irrigation, not in agrarian methods. Because the soils were fine, rich, and constantly replenished by the floodwaters’ silt, soil tillage was light work. Farmers sowed a combination of wheat, millet, sesame, and barley (the basis for beer, a staple of their diet).

Crossroads of Southwest Asia

Though its soil was rich and water was abundant, southern Mesopotamia had few other natural resources apart from the mud, marsh reeds, spindly trees, and low-quality limestone that served as basic building materials. To obtain high-quality stone, metal, dense wood, and other materials for constructing and embellishing their cities with their temples and palaces, Mesopotamians interacted with the inhabitants of surrounding regions. In return for their exports of textiles, oils, and other commodities, Mesopotamians imported cedar wood from Lebanon, copper and stones from Oman, more copper from Turkey and Iran, and the precious blue gemstone called lapis lazuli, as well as ever-useful tin, from faraway Afghanistan. Maintaining trading contacts was easy, given Mesopotamia’s open boundaries on all sides. The area became a crossroads for the peoples of Southwest Asia, including Sumerians, who concentrated in the south; Hurrians, who lived in the north; and Akkadians, who populated western and central Mesopotamia. Trade and migration contributed to the growth of cities throughout the river basin, beginning with the Sumerian cities of southern Mesopotamia.

The World’s First Cities

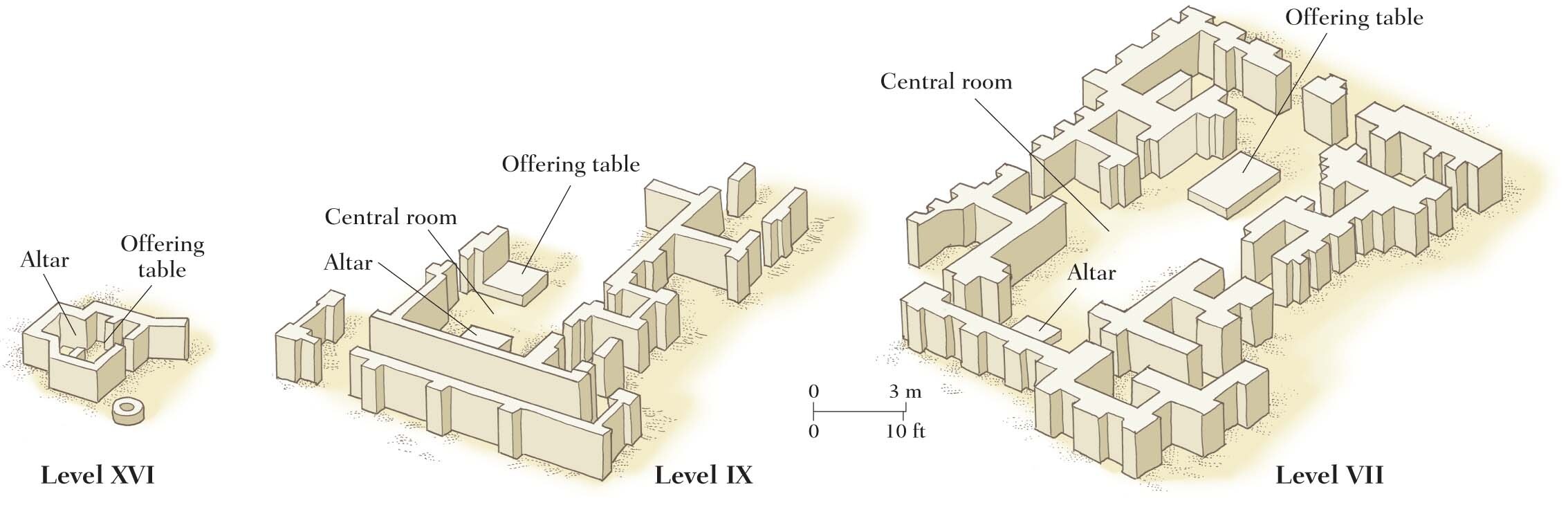

During the first half of the fourth millennium BCE, a demographic transformation occurred in the Tigris-Euphrates river basin, especially in the southern area called Sumer. The population expanded as a result of the region’s agricultural bounty, and many Mesopotamians migrated from country villages to centers that eventually became cities. (A city is a large, well-defined urban area with a dense population.) The earliest Sumerian cities—Uruk, Eridu, and Nippur—developed over about 1,000 years, dominating the southern part of the floodplain by 3500 BCE. Buildings of mud brick show successive layers of urban development, as at Eridu, where more than twenty reconstructed temples were piled atop one another across four millennia, resulting in a final temple that rose from a platform like a mountain, visible for miles in all directions.

As the temple grew skyward, the village expanded outward and became a city. From their homes in temples located at the center of cities, the cities’ gods broadcast their powers. In return, urbanites provided luxuries, fine clothes, and enhanced lodgings for the gods and their priests. In Sumerian cosmology, created by ruling elites, humans existed solely to serve the gods, so the urban landscape reflected this fact: a temple at the core, with goods and services flowing to the center and with divine protection and justice flowing outward.

Some thirty-five of these politically equal city-states with religious sanctuaries dotted the southern plain of Mesopotamia. Sumerian ideology glorified a way of life and a territory based on politically equal city-states, each with a guardian deity and sanctuary supported by its inhabitants. (A city-state is a political organization based on the authority of a single, large city that controls outlying territories.) Because early Mesopotamian cities served as meeting places for peoples and their deities, they gained status as religious and economic centers. Whether enormous (like Uruk and Nippur) or modest (like Ur and Abu Salabikh), all cities were spiritual, economic, and cultural homes for Mesopotamian subjects.

Simply making a city was therefore not enough: urban design reflected the city’s role as a wondrous place to pay homage to the gods and their human intermediary, the king. Within their walls, early cities contained large houses separated by date palm plantations and extensive sheepfolds. As populations grew, the Mesopotamian cities became denser, houses became smaller, and new suburbs spilled out beyond the old walls. The typical layout of Mesopotamian cities reflected a common pattern: a central canal surrounded by neighborhoods of specialized occupational groups. The temple marked the city center, with the palace and other official buildings on the periphery. In separate quarters for craft production, families passed down their trades across generations. In this sense, the landscape of the city mirrored the growing social hierarchies (distinctions between the privileged and the less privileged).

More information

Three different temples are labeled by level. The smallest temple is at level XVI or 16 and it is just a small room with an offering table and an altar. The next temple is much larger and complicated with a central room that contains the altar and offering table. The level for this temple is IX or nine. The last temple is the largest, contains a huge central room with a large offering table, and alter table. There are many smaller rooms around the central room. This temple is at level VII or 7.

Gods and Temples

The worldview of the Sumerians and, later, the Akkadians of Mesopotamia, included a belief in a group of gods that shaped their political institutions and controlled everything—including the weather, fertility, harvests, and the underworld. As depicted in the Epic of Gilgamesh (a second-millennium BCE composition based on oral tales about Gilgamesh, a historical but mythologized king of Uruk), the gods could give but could also take away—with droughts, floods, and death. Gods, and the natural forces they controlled, had to be revered and feared. Faithful subjects imagined their gods as immortal beings whose habits were capricious and who had contentious relationships and gloriously work-free lives.

Each major god of the Sumerian pantheon (an officially recognized group of gods and goddesses) dwelled in a lavish temple in a particular city that he or she had created; for instance, Enlil, god of air and storms, dwelled in Nippur; Enki (also called Ea), god of water, in Eridu; Nanna, god of the moon, in Ur; and Inanna (also called Ishtar), goddess of love, fertility, and war, in Uruk. These temples, and the patron deity housed within, gave rise to each city’s character, institutions, and relationships with its urban neighbors. Inside these temples, benches lined the walls, with statues of humans standing in perpetual worship of the deity’s images. By the end of the third millennium BCE, the temple’s platform base had changed to a stepped platform called a ziggurat, with the main temple on top. Surrounding the ziggurat were buildings that housed priests, officials, laborers, and servants.

More information

The first Ziggurat of Mesopotamia, a rectangular stepped tower that is very tall and wide. A long staircase is at the front that leads from the ground to the top of the tower.

Temples functioned as the god’s estate, engaging in all sorts of productive and commercial activities. Temple dependents cultivated cereals, fruits, and vegetables by using extensive irrigation and cared for flocks of livestock. Other temples operated workshops for manufacturing textiles and leather goods, employing craftworkers, metalworkers, masons, and stoneworkers. Enormous labor forces were involved in maintaining this high level of production.

Royal Power, Families, and Social Hierarchy

Like the temples, royal palaces reflected the power of the ruling elite. Royal palaces appeared around 2500 BCE and served as the official residence of a ruler, his family, and his entourage. As access to palaces and temples over time became limited, gods and kings became inaccessible to all but the most elite. Although located at the edge of cities, palaces were the symbols of permanent secular, military, and administrative authority distinct from the temples’ spiritual and economic power.

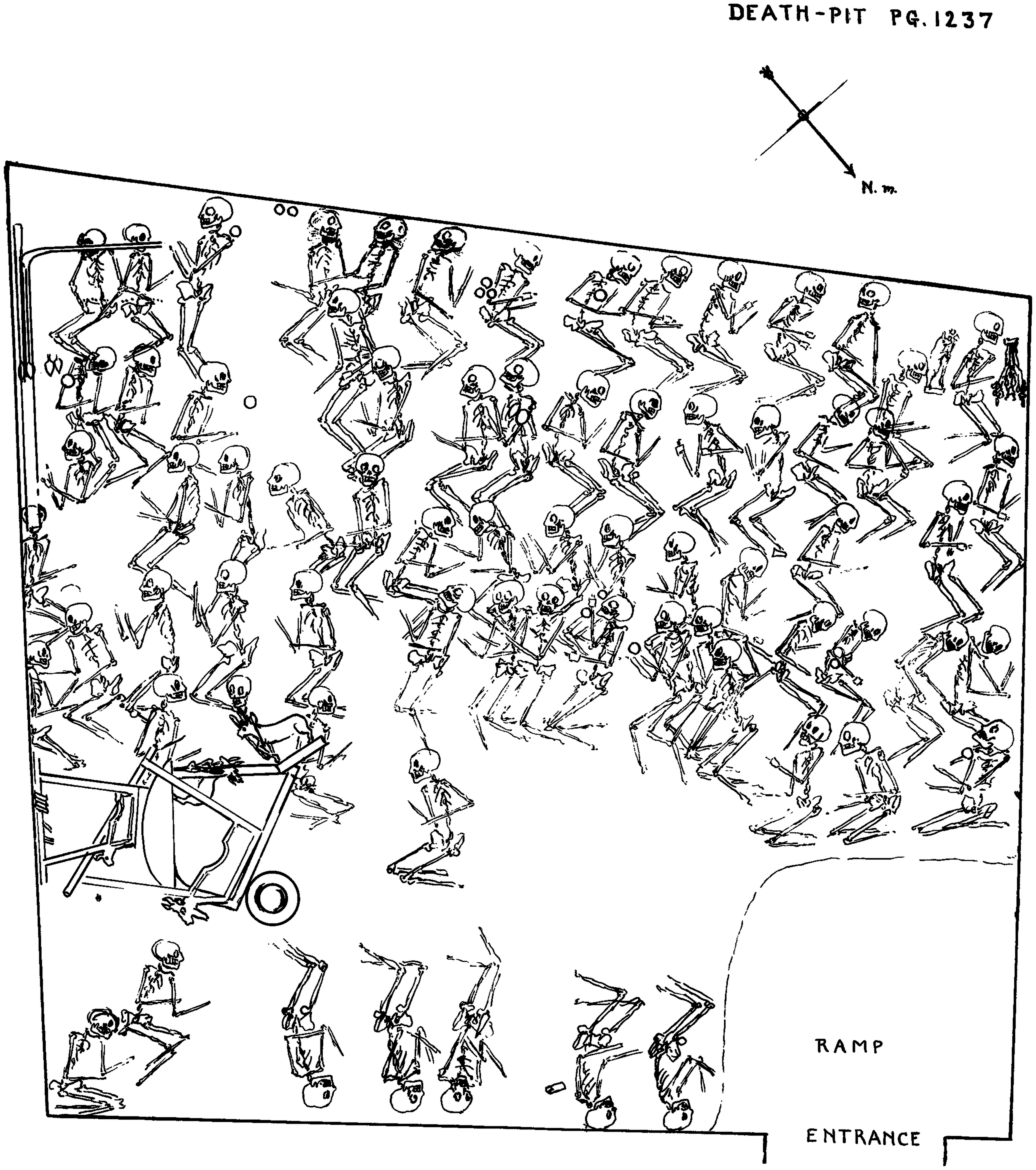

The Royal Cemetery at Ur shows how Mesopotamian rulers used elaborate burial arrangements to reinforce their religious and socioeconomic hierarchies. Housed in a mud-brick structure, the royal burials held not only the primary remains but also the bodies of more than eighty men and women who had been sacrificed. Huge vats for cooked food, bones of animals, drinking vessels, and musical instruments suggest the lifestyle of those who joined their masters in the graves. Honoring the royal dead by including their followers and possessions in their tombs underscored the social hierarchies—including the vertical ties between humans and gods—that were the cornerstone of these early city-states.

Social hierarchies were an important part of the fabric of Sumerian city-states. Ruling groups secured their privileged access to economic and political resources by erecting systems of bureaucracies, priesthoods, and laws. Priests and bureaucrats served their rulers well, championing rules and norms that legitimized the political leadership. Occupations within the cities were highly specialized, and a list of professions circulated across the land so that everyone could know his or her place in the social order. The king and priest in Sumer were at the top of the list, followed by bureaucrats (scribes and household accountants), supervisors, and craftworkers, such as cooks, jewelers, gardeners, potters, metalsmiths, and traders. There were also independent merchants who risked long-distance trading ventures, hoping for a generous return on their investment. The biggest group, which was at the bottom of the hierarchy, comprised workers who were not enslaved but were dependent on their employers’ households. Movement among economic classes was not impossible but, as in many traditional societies, it was rare.

More information

A black-and-white drawing of Death Pit 1237 from the Royal Tombs of Ur in Mesopotamia. The drawing depicts 74 skeletons scattered around the room and shows an entrance with a ramp in the bottom right corner of the pit. Several of the skeletons face the entrance, as though standing guard.

The family and the household provided the bedrock for Sumerian society, and its patriarchal organization, dominated by the senior male, reflected the balance between women and men, children and parents. The family consisted of the husband and wife bound by a contract: she would provide children, preferably male, while he provided support and protection. Monogamy was the norm unless there was no son, in which case a second wife or an enslaved woman would bear male children to serve as the married couple’s offspring. Adoption was another way to gain a male heir. Sons would inherit the family’s property in equal shares, while daughters would receive dowries necessary for successful marriage into other families. Some women joined the temple staff as priestesses and gained economic autonomy that included ownership of estates and productive enterprises, although their fathers and brothers remained responsible for their well-being.

First Writing and Early Texts

Mesopotamia was the birthplace of the world’s first writing system, inscribed to promote the economic power of the temples and kings. Those who wielded new writing tools were scribes; from the very beginning they were near the top of the social ladder, under the major power brokers—the king (lugal in Sumerian, literally meaning “big man”) and the priests. As the writing of texts became more important to the social fabric of cities, and facilitated information sharing across wider spans of distance and time, scribes consolidated their elite status.

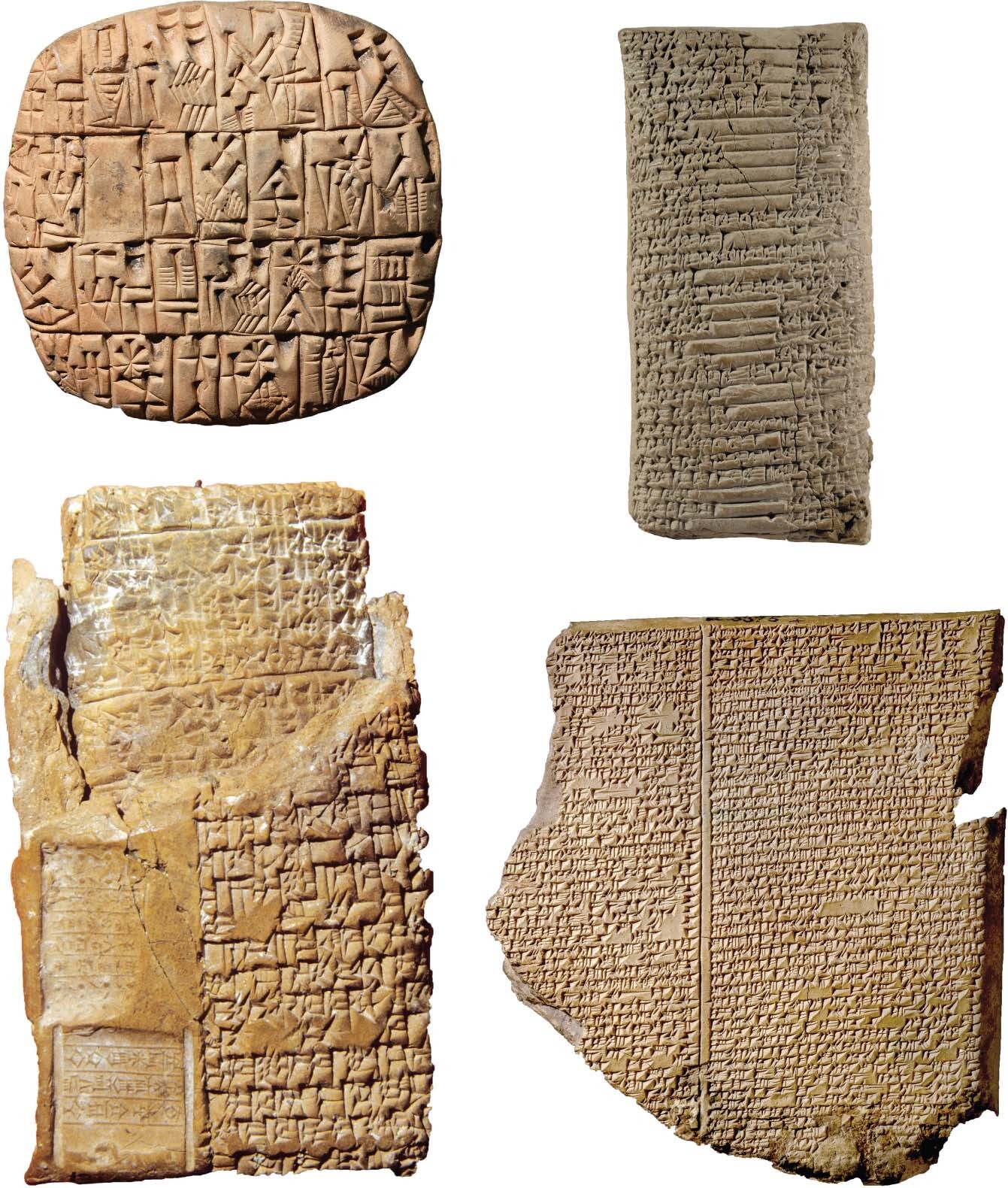

Mesopotamians were the world’s first record keepers and readers. The precursors to writing appeared in Mesopotamian societies when farming peoples and officials who had been using clay tokens and images carved on stones to seal off storage areas began to use them to convey messages. These images, when combined with numbers drawn on clay tablets, could record the distribution of goods and services.

More information

A round cuneiform tablet made of clay with a series of medium-sized wedge-shaped markings covering the surface.

A rectangular cuneiform tablet covered in tight rows of tiny markings.

A cuneiform letter sealed in a clay envelope. Both the letter and envelope are covered in small markings.

A broken cuneiform tablet with a straight line down the middle and a tiny script on either side of it.

Around 3200 BCE, someone, probably in Uruk, understood that the marks (most were pictures of objects) could also represent words or sounds. Before long, scribes connected visual symbols with sounds, and sounds with meanings, and they discovered they could record messages by using abstract symbols or signs to denote concepts. Such signs later came to represent syllables, the building blocks of words. By impressing signs into wet clay with the cut end of a reed, scribes pioneered a form of wedge-shaped writing that we call cuneiform; it filled tablets with information that was intelligible to anyone who could decipher it, even in faraway locations or in future generations. Developing over 800 years, this Sumerian innovation enhanced the urban elites’ ability to trade goods, to control property, and to transmit ideas through literature, historical records, and sacred texts. The result was a profound change in human experience, because representing symbols of spoken language facilitated an extension of communication and memory.

Much of what we know about Mesopotamia rests on scholars’ ability to decipher cuneiform script. By around 2400 BCE, texts began to describe the political makeup of southern Mesopotamia, giving details of its history and economy. Adaptable to different languages, cuneiform script was borrowed by other peoples in Mesopotamia to write not only Semitic languages such as Akkadian and, much later, Old Persian, but also the languages of the Hurrians and the Hittites.

City life and literacy also gave rise to written narratives, the stories of a “people” and their origins. “The Temple Hymns,” written around 2100 BCE, describe thirty-five divine sanctuaries. The Sumerian King List, known from texts written around 2000 BCE, recounts the reigns of kings by city and dynasty and narrates the long reigns of legendary kings before the so-called Great Flood. A crucial event in Sumerian identity, the Great Flood, a pastoral-focused version of which is also found in biblical narrative, explained Uruk’s demise as the gods’ doing. Flooding was the most powerful natural force in the lives of those who lived by rivers, and it helped shape the foundations of Mesopotamian societies.

Cities Begin to Unify into “States”

No single city-state dominated the whole of Mesopotamia in the fourth and third millennia BCE, but the most powerful and influential were the Sumerian city-states (2850–2334 BCE) and their successor, the Akkadian territorial state (2334–2193 BCE). In the north, Hurrians urbanized their rich agricultural zone around 2600 BCE, including cities at Urkesh and Tell Brak. (See Map 2.3.)

Sumerian city-states, with their expanding populations, soon found themselves competing for agrarian lands, scarce water, and lucrative trade routes. And as pastoralists far and wide learned of the region’s bounty, they journeyed in greater numbers to the cities, fueling urbanization and competition. The world’s first great conqueror—Sargon the Great (r. 2334–2279 BCE), king of Akkad—emerged from one of these cities. By the end of his reign, he had united (by force) the independent Mesopotamian cities south of modern-day Baghdad and brought the era of competitive independent city-states to an end. Sargon’s unification of the southern cities by alliance, though relatively short-lived, created a territorial state. (A territorial state is a form of political organization that holds authority over a large population and landmass; its power extends over multiple cities.) Sargon’s dynasty sponsored monumental architecture, artworks, and literary works, which in turn inspired generations of builders, architects, artists, and scribes. And by encouraging contact with distant neighbors, many of whom adopted aspects of Mesopotamian culture, the Akkadian kings increased the geographic reach of Mesopotamian influence. Just under a century after Sargon’s death, foreign tribesmen from the Zagros Mountains conquered the capital city of Akkad around 2190 BCE, setting the beginning of a pattern that would fuel epic history writing, namely the struggles between city-state dwellers and those on the margins who lived a simpler way of life. The impressive state created by Sargon was made possible by Mesopotamia’s early innovations in irrigation, urban development, and writing. While Mesopotamia led the way in creating city-states, Egypt went a step further, unifying a 600-mile-long region under a single ruler.

More information

Map 2.3 is titled, “The Spread of Cities in Mesopotamia and the Akkadian State, 2600-2200 B C E.” The map depicts three regions that came under Akkadian power between 2334 and 2193 B C E: Southern alluvium (Sumer) cities before 2600 B C E (these include Susa, Girsu, Lagash, Ur, Eridu, Uruk, and Umman); Northern alluvium (Akkad) cities before 2600 B C E (Tell Agrab, Kish, and Sippar); and Northern Mesopotamian cities after 2600 B C E (including Urkesh, Ashur, Mari, Nineveh, Bassetki, Tell Brak, Ebla). The map also shows three cities outside the reach of Akkadian power: Per Hussein, Kultepe, and Troy.

MAP 2.3 | The Spread of Cities in Mesopotamia and the Akkadian State, 2600–2200 BCE

Urbanization began in the southern river basin of Mesopotamia and spread northward. Eventually, the region achieved unification under Akkadian power.

- According to this map, what natural features influenced the location of Mesopotamian cities?

- Where were cities located before 2600 BCE, as opposed to afterward? What does the area under Akkadian power suggest that the Akkadian territorial state was able to do?

- How did the expansion northward reflect the continued influence of geographic and environmental factors on urbanization?

Glossary

- city

- Highly populated concentration of economic, religious, and political power. The first cities appeared in river basins, which could produce a surplus of agriculture. The abundance of food freed most city inhabitants from the need to produce their own food, which allowed them to work in specialized professions.

- city-state

- Political organization based on the authority of a single, large city that controls outlying territories.

- scribes

- Those who mastered writing and used it to document economic transactions, keep lists, and record religious and literary texts; from the very beginning, they were at the top of the social ladder, under the major power brokers.