“The Gift of the Nile”: Egypt

In Egypt, complex societies grew on the banks of the Nile River, and by the third millennium BCE their peoples created a distinctive culture and a powerful, prosperous state. The earliest inhabitants along the banks of the Nile were a mixed people. Some had migrated from the eastern and western deserts in Sinai and Libya as these areas grew barren from climate change. Others came from the Mediterranean. Equally important were peoples who trekked northward from Nubia and central Africa. Ancient Egypt was a melting pot where immigrants blended cultural practices and technologies.

Like Mesopotamia, Egypt had densely populated areas whose inhabitants depended on irrigation, built monumental architecture, gave their rulers immense authority, and created a complex social order based in commercial and devotional centers. Yet the ancient Egyptian culture was profoundly shaped by its geography. The environment and the natural boundaries of deserts, river rapids, and sea dominated the country and its inhabitants. Only about 3 percent of Egypt’s land area was cultivable, and almost all of that cultivable land was in the Nile Delta—the rich alluvial land lying between the river’s two main branches as it flows north of modern-day Cairo into the Mediterranean Sea. This environment shaped Egyptian society’s unique culture.

The Nile River and Its Floodwaters

Knowing Egypt requires appreciating the pulses of the Nile. The world’s longest river, it stretches 4,238 miles from its sources in the highlands of central Africa to its destination in the Mediterranean Sea. Egypt was deeply attached to sub-Saharan Africa; not only did its waters and rich silt deposits come from the African highlands, but much of its original population had migrated into the Nile Valley from the west and the south many millennia earlier.

The Upper Nile is a sluggish river that cuts through the Sahara Desert. Rising out of central Africa and Ethiopia, its two main branches—the White and Blue Niles—meet at present-day Khartoum and then scour out a single riverbed 1,500 miles long to the Mediterranean. The annual floods gave the basin regular moisture and enriched the soil. Although the Nile’s floodwaters did not fertilize or irrigate fields as broad as those in Mesopotamia, they created green belts flanking the broad waterway. These gave rise to a society whose culture stretched along the navigable river and its carefully preserved banks. Away from the riverbanks, on both sides, lay a desert rich in raw materials but largely uninhabited. (See Map 2.4.) Egypt had no fertile hinterland like the sprawling plains of Mesopotamia. In this way, Egypt was arguably the most river-focused of the river-basin cultures.

The Nile’s predictability as the source of life and abundance shaped the character of the people and their culture. In contrast to the wild and uncertain Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, the Nile was gentle, bountiful, and reliable. During the summer, as the Nile swelled, local villagers built earthen walls that divided the floodplain into basins. By trapping the floodwaters, these basins captured the rich silt washing down from the Ethiopian highlands. Annual flooding meant that the land received a new layer of topsoil every year. The light, fertile soils made planting simple. Peasants cast seeds into the alluvial soil and then had their livestock trample them to the proper depth. The never-failing sun, which the Egyptians worshipped, ensured an abundant harvest. In the early spring, when the Nile’s waters were at their lowest and no crops were under cultivation, the sun dried out the soil.

The peculiarities of the Nile region distinguished it from Mesopotamia. The Greek historian and geographer Herodotus noted 2,500 years ago that Egypt was the gift of the Nile and that the entire length of its basin was one of the world’s most self-contained geographical entities. Bounded on the north by the Mediterranean Sea, on the east and west by deserts, and on the south by waterfalls, Egypt was destined to achieve a common culture. Due to these geographical features, the region was far less open to outsiders than was Mesopotamia, which was situated at a crossroads. Egypt created a common culture by balancing a struggle of opposing forces: the north or Lower Egypt versus the south or Upper Egypt; the black, rich soil versus the red sand; life versus death; heaven versus earth; order versus disorder. For Egypt’s rulers the primary task was to bring stability or order, known as ma’at, out of these opposites. The Egyptians believed that keeping chaos, personified by the desert and its marauders, at bay through attention to ma’at would allow all that was good and right to occur.

More information

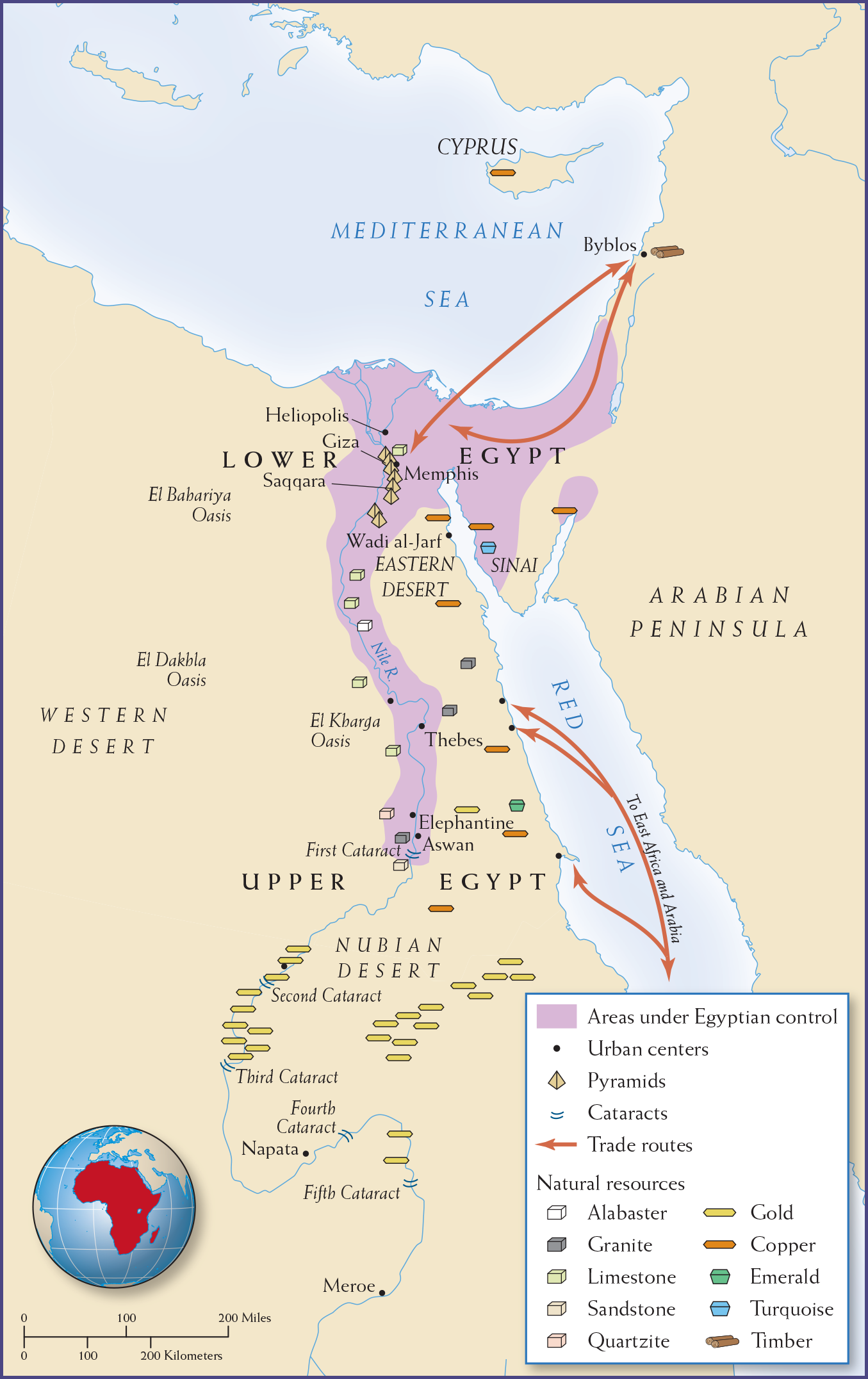

Map 2.4 is titled, “Old Kingdom Egypt, during 2686-2181 B C E.” The areas under Egyptian control (all of Lower Egypt on either side of the Nile to the Mediterranean Sea, as well as most of the Sinai Peninsula), urban centers (running north from the area of Fifth Cataract to the Mediterranean, they are Meroe, Napata, Aswan, Elephantine, Thebes, Wadi al-Jarf, and Heliopolis, as well as Byblos on the coast near Cyprus), and pyramids (concentrated in lower Egypt between Wadi al-Jarf and Heliopolis) are marked on the map. The map also shows trade routes up and down the Red Sea and between Heliopolis and Byblos, as well as natural resources (timber in Byblos, gold between the Second and Fifth Cataracts, alabaster, granite, limestone, sandstone, and quartzite along the Nile north of the First Cataract, emerald near Elephantine, and turquoise and copper in the Sinai Peninsula.

MAP 2.4 | Old Kingdom Egypt, 2686–2181 BCE

Old Kingdom Egyptian society reflected a strong influence from its geographical location.

- What geographical features contributed to Egypt’s isolation from the outside world and the people’s sense of their unity?

- What natural resources enabled the Egyptians to build the Great Pyramids? What resources enabled the Egyptians to fill those pyramids with treasures?

- Based on the map, why do you think it was important to the people and their rulers for Upper and Lower Egypt to be united?

The Egyptian State and Dynasties

Once the early Egyptians harnessed the Nile to agriculture, the area changed quickly from scarcely inhabited to socially complex. A king, later called the pharaoh and considered semidivine, was at the center of Egyptian life (Egyptian kings did not use the title pharaoh until the mid to late second millennium BCE). He ensured that the forces of nature, in particular the regular flooding of the Nile, continued without interruption. This task had more to do with appeasing the gods than with running a complex hydraulic system. The king protected his people from chaos-threatening invaders from the eastern desert, as well as from Nubians on the southern borders. In wall carvings, artists portrayed early kings carrying the shepherd’s crook and the flail, indicating their responsibility for the welfare of their flocks (the people) and of the land. Under the king an elaborate bureaucracy organized labor and produced public works, sustaining both his vast holdings and general order throughout the realm.

The narrative of ancient Egypt’s history follows its thirty-one dynasties, spanning nearly three millennia from 3100 BCE down to its conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. (See Table 2.1.) Since the nineteenth century, scholars have recast the story around three periods of dynastic achievement: the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, and the New Kingdom. At the end of each era, cultural flourishing suffered a breakdown in central authority, known respectively as the First, Second, and Third Intermediate Periods.

|

TABLE 2.1 Dynasties of Ancient Egypt |

|

|

DYNASTY* |

DATE |

|

Predynastic Period dynasties I and II |

3100–2686 BCE |

|

Old Kingdom dynasties III–VI |

2686–2181 BCE |

|

First Intermediate Period dynasties VII–X |

2181–2055 BCE |

|

Middle Kingdom dynasties XI–XIII |

2055–1650 BCE |

|

Second Intermediate Period dynasties XIV–XVII |

1650–1550 BCE |

|

New Kingdom dynasties XVIII–XX |

1550–1070 BCE |

|

Third Intermediate Period dynasties XXI–XXV |

1070–747 BCE |

|

Late Period dynasties XXVI–XXXI |

747–332 BCE |

|

*The term dynasty generally refers to a series of rulers who are related to one another. Intermediate periods mark breaks between the kingdoms (Old, Middle, and New). While scholars make attempts to synchronize the dates with modern chronology and other events in the ancient world, the succession of rulers comes from Egyptian texts. The term pharaoh, as a title for the Egyptian king, came into use in the New Kingdom. |

|

|

Source: Compiled from Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson, eds., The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (London: British Museum Press, 1995), pp. 310–11. |

|

Kings, Pyramids, and Cosmic Order

The Third Dynasty (2686–2613 BCE) launched the foundational period known as the Old Kingdom, the golden age of ancient Egypt. By the time it began, the basic institutions of the Egyptian state were in place, as were the ideology and ritual life that legitimized the dynastic rulers.

The king presented himself to the population by means of impressive architectural spaces, and the priestly class performed rituals reinforcing his supreme status within the universe’s natural order. One of the most important rituals was the Sed festival, which renewed the king’s vitality after he had ruled for thirty years and sought to ensure the perpetual presence of water. King Djoser, from the Third Dynasty, celebrated the Sed festival at his tomb complex at Saqqara. This magnificent complex includes the world’s oldest stone structure, dating to around 2650 BCE. Here Djoser’s architect, Imhotep, designed a step pyramid that ultimately rose some 200 feet above the plain. The whole complex became a stage for state rituals that emphasized the divinity of kingship and the unity of Egypt.

More information

The Pyramid Fields of Giza, which has three small pyramids in the front and three large pyramids in the back.

The step pyramid at Djoser’s tomb complex was a precursor to the grand pyramids of the Fourth Dynasty (2613–2494 BCE). These kings erected their monumental structures at Giza, just outside modern-day Cairo and not far from the early royal cemetery site of Saqqara, where Djoser’s step pyramid stood. The pyramid of Khufu, rising 481 feet above the ground, is the largest stone structure in the world, and its corners are almost perfectly aligned to due north, west, south, and east. The oldest papyrus texts ever found—including a set of records kept by an official named Merer around 2550 BCE, which was excavated recently at the ancient port of Wadi al-Jarf—document a meticulous timetable for the gathering of stone for pyramid construction during Khufu’s reign and tabulations of food to feed workers.

Construction of pyramids entailed the backbreaking work of quarrying the massive stones, digging a canal so barges could bring them from the Nile to the base of the Giza plateau, building a harbor there, and then constructing sturdy brick ramps that could withstand the stones’ weight as workers hauled them ever higher along the pyramids’ faces. Most likely a permanent workforce of up to 21,000 laborers endured 10-hour workdays, 300 days a year, for approximately 14 years just to complete the great pyramid of Khufu. The finished product was a miracle of engineering and planning. Khufu’s great pyramid contained 21,300 blocks of stone with an average weight of 2½ tons, though some stones weighed up to 16 tons. Roughly speaking, one stone had to be put in place every 2 minutes during daylight. The stone blocks were planed so precisely that they required no mortar.

Surrounding these royal tombs at Giza were those of high officials, almost all members of the royal family. The enormous amount of labor involved in building these monuments came from peasant-workers as well as enslaved people captured and brought from Nubia and the Mediterranean. Filling these monuments with wealth for the occupants’ afterlife similarly required a range of specialized labor (from jewelers to weavers to stone carvers to furniture makers). Long-distance trade was required to bring from far away not only the jewels and precious metals (like lapis lazuli, carnelian, and silver) required for such offerings, but also the materials to construct the ships that helped make that trade possible (like timber from Byblos). Through their majesty and complex construction, the Giza pyramids reflect the degree of centralization and the surpluses in Egyptian society at this time as well as the trade and specialized labor that fueled these undertakings.

Kings used their royal tombs, and the ritual of death leading to everlasting life, to embody the state’s ideology and the principles of the Egyptian cosmos. They also employed symbols, throne names, and descriptive titles for themselves and their advisers to represent their own power and that of their administrators, the priests, and the landed elite. As in Mesopotamian city-states, the Egyptian cosmic order was one of inequality and stark hierarchy that did not seek balance among people (for it buttressed the inequalities and stark hierarchies of Egyptian society); rather, Egyptian religion sought balance between universal order (ma’at) and disorder. It was the job of the king to maintain this cosmic order for eternity.

Gods, Priesthood, and Magical Power

Egyptians understood their world as inhabited by three groups: gods, kings, and the rest of humanity. Official records showed representations of only gods and kings. Yet the people did not confuse their kings with gods—at least during the kings’ lifetimes. Mortality was the bar between rulers and deities; after death, kings joined the gods whom they had represented while alive.

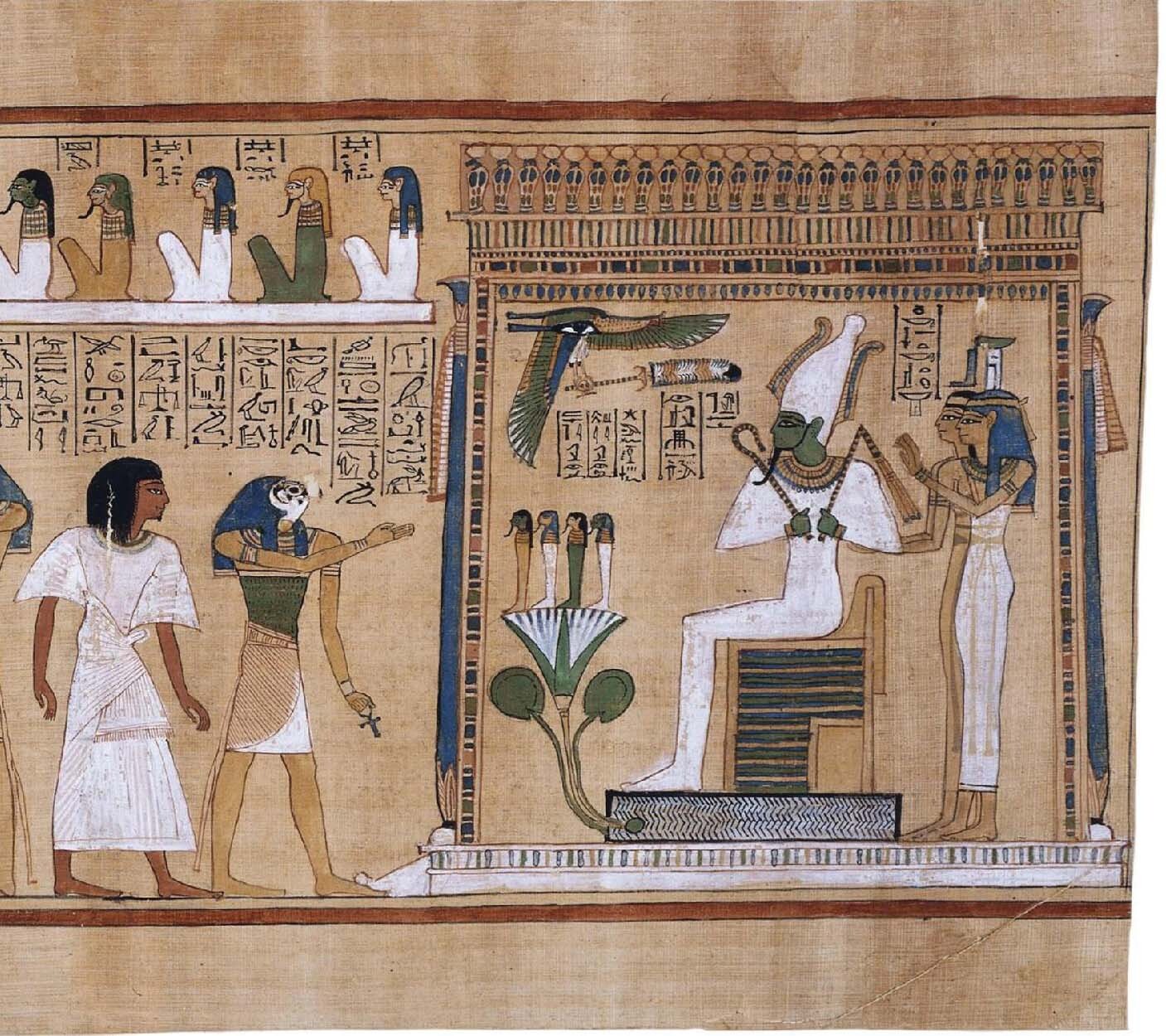

As in Mesopotamia, every region in Egypt had its resident god. Some gods, such as Amun (believed to be physically present in Thebes, the political center of Upper Egypt), transcended regional status because of the importance of their hometown. Over the centuries the Egyptian gods evolved, combining often-contradictory aspects into single deities, including Horus, the sky god of kinship; Osiris, the god of regeneration and the underworld; Isis, who represented the ideals of sisterhood and motherhood; Hathor, the goddess of childbirth and love; Ra, the sun god; and Amun, a creator considered to be the hidden god.

More information

A page from the Book of the Dead. The page shows a falcon-headed Horus bringing a scribe named Hunefer into the presence of Osiris, who is shown seated under a canopy holding a crook and flail across his chest, with his sisters Isis and Nephthys standing behind him. Four small human figures stand on a fan-like structure protruding from Osiris’s throne. At the top left corner, five human figures sit facing towards the left side of the illustration.

Official religious practices took place in the main temples. The king and his agents offered respect, adoration, and thanks to the gods in their temples. In return, the gods maintained order and nurtured the king and—through him—all humanity. In this contractual relationship, the gods were passive while the kings were active, a difference that reflected their unequal relationship.

The tasks of regulating religious rituals and mediating among gods, kings, and society fell to one specialist class: the priesthood. Creating this class required elaborate rules for selecting and training the priests. Only priests could enter the temples’ inner sanctuaries, and the gods’ statues left the temples only for great festivals. Thus, priests monopolized communication between spiritual powers and their subjects.

Unofficial religion was also important. Ordinary Egyptians matched their elite rulers in faithfulness to the gods, but their distance from temple life caused them to find different ways to fulfill their religious needs and duties. They visited local shrines, where they prayed, made requests, and left offerings to the gods.

Unlike modern sensibilities that might see magic as opposed to, or different from, categories such as religion or medicine, Egyptians saw magic (personified by the god Heka) as a category closely intertwined with, if not indistinguishable from, the other two. Magic, or Heka, was a force that was present at creation and preexisted order and chaos. Magic had a special importance for commoners, who believed that amulets held extraordinary powers, such as preventing illness and guaranteeing safe childbirth. To deal with profound questions, commoners looked to omens and divination. Like the elites, commoners attributed supernatural powers to animals. Chosen animals received special treatment in life and after death: for example, the Egyptians adored cats, whom they kept as pets and whose image they used to represent certain deities. Apis bulls, sacred to the god Ptah, merited special cemeteries and mourning rituals. Ibises, dogs, jackals, baboons, lizards, fish, snakes, crocodiles, and other beasts associated with deities enjoyed similar privileges.

Spiritual expression was central to Egyptian culture at all levels, and religion helped shape other cultural achievements, including the development of a written language.

Writing and Scribes

Egypt, like Mesopotamia, was a scribal culture. By the middle of the third millennium BCE, literacy was well established among small circles of scribes in Egypt and Mesopotamia. The fact that few individuals were literate heightened the scribes’ social status. Most high-ranking Egyptians were also trained as scribes for the king’s court, the army, or the priesthood. Some kings and members of the royal family learned to write as well. Although in both cultures writing may have emerged in response to economic needs, people in Egypt soon grasped its utility for commemorative and religious purposes.

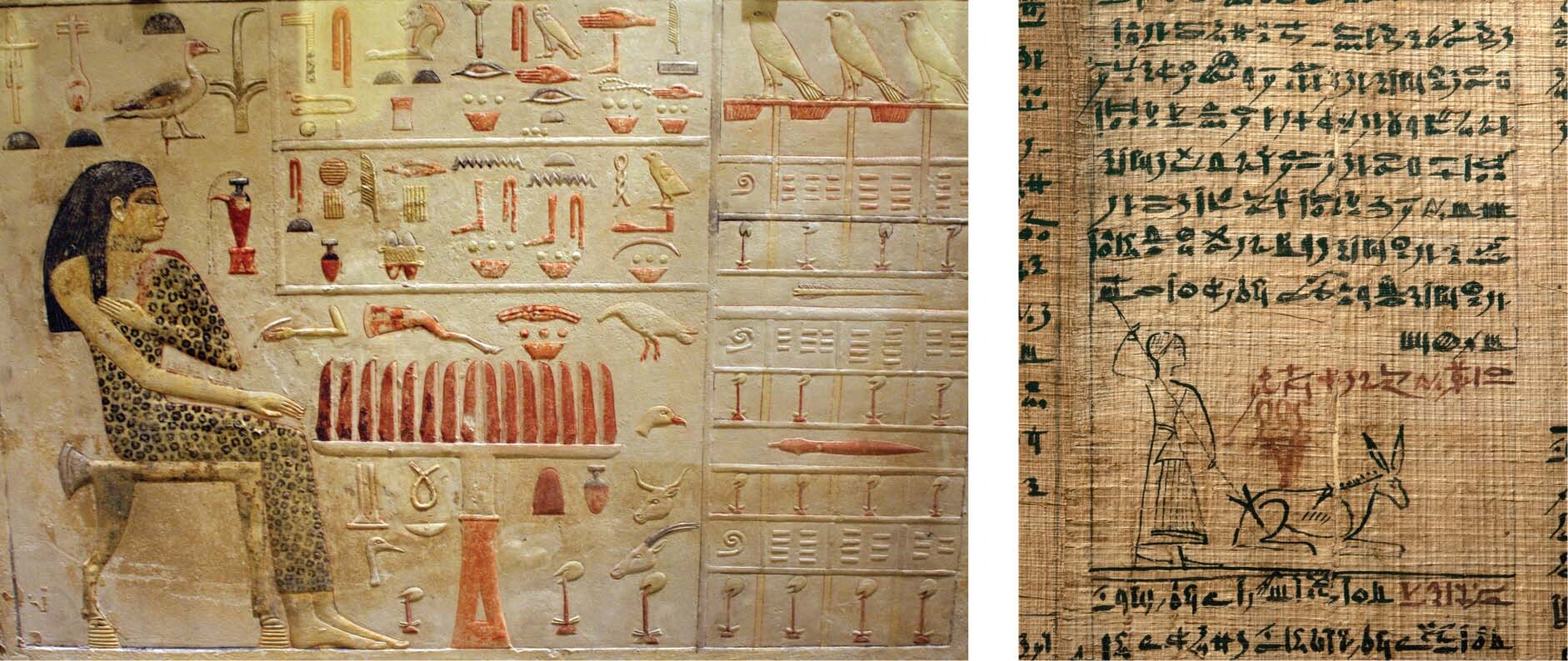

More information

Funerary relief of a person and many hieroglyphs. The person is sitting at a table. There are various hieroglyphs located around the image

An Egyptian hieratic script. The script is written with ink on papyrus and depicts a person spearing an animal in the drawing’s center, with script both above and below it.

Ancient Egyptians used two forms of writing. Elaborate hieroglyphs (from the Greek “sacred carving”) served in formal temple, royal, or divine contexts. More common, however, was hieratic writing, a cursive script written with ink on papyrus or pottery. (Demotic writing, from the Greek demotika, meaning “popular” or “in common use,” developed much later and became the vital transitional key on the Rosetta Stone that ultimately allowed the nineteenth-century decipherment of hieroglyphs.) Used for record keeping, hieratic writing also found uses in letters and works of literature—including narrative fiction, manuals of instruction and philosophy, cult and religious hymns, love poems, medical and mathematical texts, collections of rituals, and mortuary books.

Literacy spread first among upper-class families. Most students started training when they were young. After mastering the copying of standard texts in hieratic cursive or hieroglyphs, students moved on to literary works. The upper classes prized literacy as proof of high intellectual achievement. When elites died, they had their student textbooks placed alongside their corpses as evidence of their talents. The literati produced texts mainly in temples, where these works were also preserved. Writing in hieroglyphs and the composition of texts in hieratic, and later demotic, script continued without break in ancient Egypt for almost 3,000 years.

The Prosperity and Demise of Old Kingdom Egypt

Cultural achievements, agrarian surpluses, and urbanization ultimately led to higher standards of living and rising populations. Under pharaonic rule, Egypt enjoyed spectacular prosperity. Its population swelled from 350,000 in 4000 BCE to 1 million in 2500 BCE and nearly 5 million by 1500 BCE. However, expansion and decentralization eventually exposed the weaknesses of the Old and Middle Kingdom dynasties.

The state’s success depended on administering resources skillfully, especially agricultural production and labor. Everyone, from the most powerful elite to the workers in the field, was part of the system. In principle, no one possessed private property; in practice, Egyptians treated land and tools as their own—but submitted to the intrusions of the state. The state’s control over taxation, prices, and the distribution of goods required a large bureaucracy that maintained records, taxed the population, appeased the gods, organized a strong military, and aided local officials in regulating the Nile’s floodwaters.

Royal power, along with the Old Kingdom, collapsed in the three years following the death of Pepy II in 2184 BCE. Local magnates assumed hereditary control of the government in the provinces and treated lands previously controlled by the royal family as their personal property. An extended drought strained Egypt’s extensive irrigation system, which could no longer water the lands that fed the region’s million inhabitants. (See Current Trends in World History: Climate Change at the End of the Third Millennium BCE in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley.) In this so-called First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BCE), local leaders plunged into bloody regional struggles to keep the irrigation works functioning for their own communities until the century-long drought ended. Although the Old Kingdom declined, it established institutions and beliefs that endured and were revived several centuries later.