The Indus River Valley: A Parallel Culture

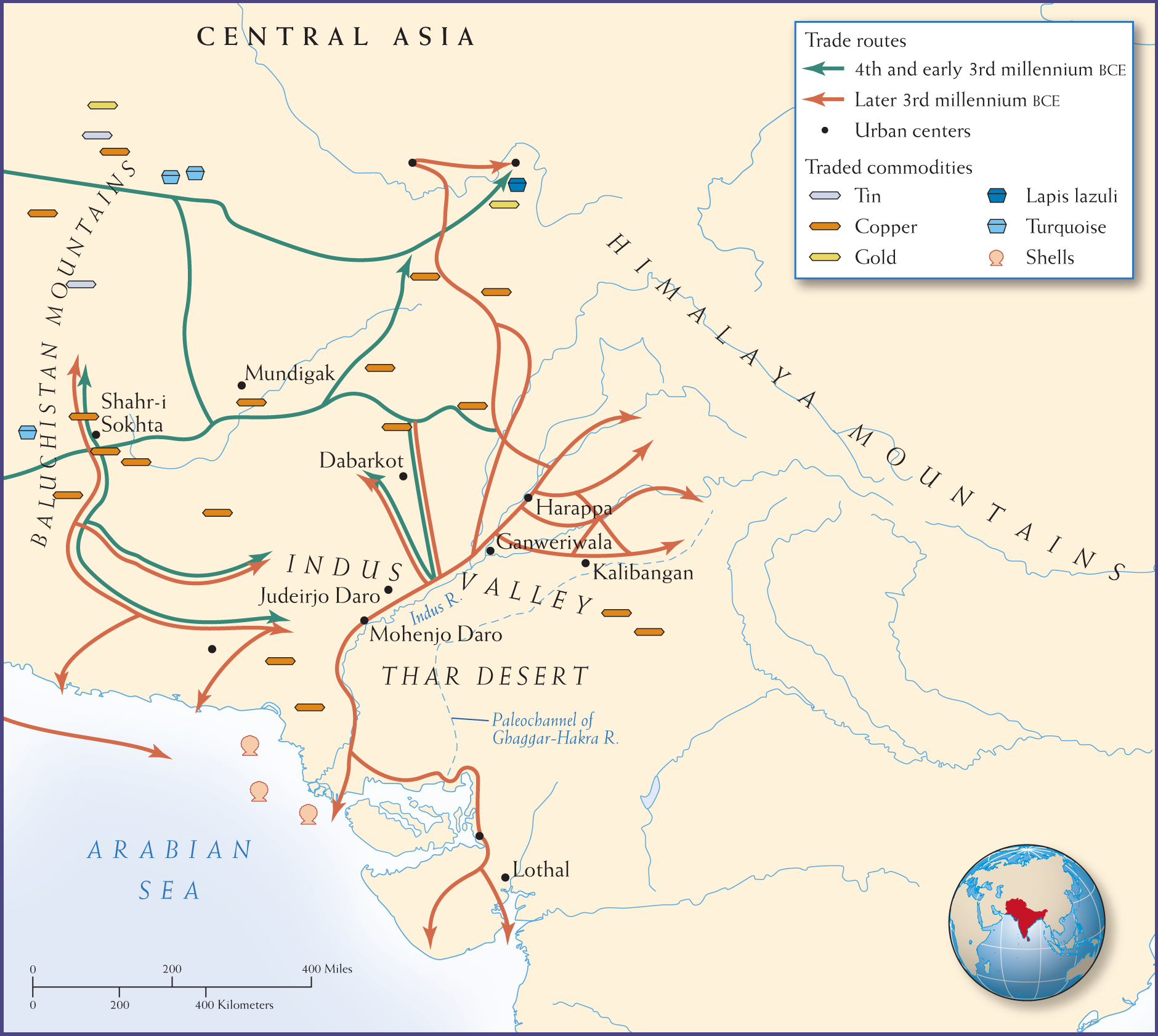

Cities emerged in the Indus River valley in South Asia in the mid-third millennium BCE. The urban culture of the Indus area is called “Harappan” after the urban site of Harappa that arose on the banks of the Ravi River, a tributary of the Indus. Developments in the Indus basin reflected local tradition combined with strong influences from Iranian plateau peoples, as well as indirect influences from distant Mesopotamian cities. Villages appeared around 5000 BCE on the Iranian plateau along the Baluchistan Mountain foothills, to the west of the Indus. By the early third millennium BCE, frontier villages had spread eastward to the fertile banks of the Indus River and its tributaries. (See Map 2.5.) The river-basin settlements soon yielded agrarian surpluses that supported greater wealth, more trade with neighbors, and public works. Urbanites of the Indus region and the Harappan peoples began to fortify their cities and to undertake public works similar in scale to those in Mesopotamia, but strikingly different in function.

The Indus Valley ecology boasted many advantages—especially compared to the area near the Ganges River, the other great waterway of the South Asian landmass. The melting snows in the Himalayas watered the semitropical Indus Valley, ensuring flourishing vegetation, plus the region did not suffer the yearly monsoon downpours that flooded the Ganges plain. The expansion of agriculture in the Indus basin, as in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China, depended on the Indus River’s annual floods to replenish the soil and avert droughts. From June to September, the river inundated the plain. New evidence has suggested that the monsoons also brought seasonal flows of water into long-dried-up riverbeds (especially the so-called paleochannel of the Ghaggar-Hakra, a river that had dried up almost 3,000 years before Harappan society began to thrive). This evidence poses a unique question about river-fueled society in the third millennium BCE: How did the Harappan settlements clustered along this paleochannel to the east of the Indus River harness a seasonal flow of water into an otherwise-dried-up riverbed, as compared with a year-round river?

Current Trends in World History

Climate Change at the End of the Third Millennium BCE in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley

During the long third millennium BCE, the first urban centers in Egypt, Mesopotamia, Iran, central Asia, and South Asia flourished and grew in complexity and wealth in a wet and cool climate. This smooth development was sharply if not universally interrupted beginning around 2200 BCE. Both archaeological and written records agree that across Afro-Eurasia, most of the urban, rural, and pastoral societies underwent radical change. Those watered by major rivers were selectively destabilized, while the settled communities on the highland plateaus virtually disappeared. After a brief hiatus, some recovered, completely reorganized, and used new technologies to manage agriculture and water. The causes of this radical change have been the focus of much interest.

After four decades of research by climate specialists working together with archaeologists, a consensus has emerged that climate change toward a warmer and drier environment contributed to this disruption. Whether this disruption was caused solely by human activity, in particular agriculture on a large scale, or was also related to cosmic causes such as the rotation of the earth’s axis away from the sun, is still a hotly debated topic. It was likely a combination of factors.

The urban centers dependent on the three major river systems in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley all experienced disruption. In Egypt, the hieroglyphic inscriptions tell us that the Nile no longer flooded over its banks to replenish the fields with fresh soil and with water for crops. Social and political chaos followed for more than a century. In southern Mesopotamia, the deeply downcut rivers changed course, disrupting settlement patterns and taking fields out of cultivation. Other fields were poisoned by salts brought on through overcultivation and irrigation without fallow periods. Fierce competition for water and land put pressure on the central authority. To the east and west, transhumant herders, faced with shrinking pasture for their flocks, pressed in on the river valleys, disrupting the already-challenged social and political structure of the densely urban centers.

In northern Mesopotamia, the responses to the challenges of aridity were more varied. Some centers were able to weather the crisis by changing strategies of food production and distribution. Some fell victim to intraregional warfare, while others, on the rainfall margin, were abandoned. When the region was settled again, society was differently organized. The population did not drastically decrease, but rather distributed itself across the landscape more evenly in smaller settlements that required less water and food. It appears that a similar solution was found by communities to the east on the Iranian plateau, where the inhabitants of the huge urban center of Shahr-i Sokhta abruptly left the city and settled in small communities across the oasis landscape.

The solutions found by people living in the cities of the Indus Valley also varied. Some cities, like Harappa, saw their population decrease rapidly. It seems that the bed of the river shifted, threatening the settlement and its hinterland. Mohenjo Daro, on the other hand, continued to be occupied for another several centuries, although the large civic structures fell out of use, replaced by more modest structures. The Ghaggar-Hakra (as a year-round river) had dried up long before Harappan settlements of the third millennium BCE. The urban settlements along the course of its seasonal flow had already formed as an adaptation to an earlier climate change, since their inhabitants had likely clustered along the dried-up riverbed as a topographical feature that would focus monsoon flows even in the absence of a year-round river. And to the south, on the Gujarat Peninsula, population and the number of settlements increased. They abandoned wheat as a crop, instead cultivating a kind of drought-enduring millet that originated in West Africa. Apparently, conditions there became even more hospitable, allowing farming and fishing communities to flourish well into the second millennium BCE.

The evidence for this widespread phenomenon of climate change at the end of the third millennium BCE is complex and contradictory. This is not surprising, because every culture and each community naturally had an individual response to environmental and other challenges. Those with perennial sources of fresh water were less threatened than those in marginal zones where only a slight decrease in rainfall could mean failed crops and herds. Notably, certain types of social and political institutions were resilient and introduced innovations that allowed them to adapt, while others were too rigid or shortsighted to find local solutions. A feature of human culture is its remarkable ability to adapt rapidly. When people are faced with challenges, the traits of resilience, creativity, and ingenuity lead to cultural innovation and change. This is what we can see, even in our own times, during the period of environmental stress.

More information

A photo shows a field of the type of grain known as millet.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- How did the response to drought in the Indus Valley differ from the response in Mesopotamia?

- Imagine that the climate during the third millennium BCE had not changed. How do you think this might have affected the development of ancient Egypt?

- How has our understanding of global climate change affected the way we study prehistory?

EXPLORE FURTHER

Behringer, Wolfgang, A Cultural History of Climate (2010).

Bell, Barbara, “The Dark Ages in Ancient History. 1. The First Dark Age in Egypt,” American Journal of Archaeology 75 (January 1971): 1–26.

Middleton, Guy D., Understanding Collapse: Ancient History and Modern Myths (2017).

Singh, Ajit, et al., “Counter-Intuitive Influence of Himalayan River Morphodynamics on Indus Civilisation Urban Settlements,” Nature Communications 8, article no. 1617 (2017), doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01643-9.

Weiss, Max, et al., “The Genesis and Collapse of Third Millennium North Mesopotamian Civilization,” Science (New Series) 261 (August 20, 1993): 995–1004.

More information

Map 2.5 is titled, “The Indus River Valley in the Third Millennium B C E.” Urban centers included Shahr-i Sohkta, Mundigak, Dabarkot, Judeirjo Daro, Mohenjo Daro, Harappa, Kalibangan, Ganweriwala, and Lothal. Trade routes of the fourth and early third millennium B C E traveled between the Baluchistan Mountains east toward the Indus Valley. Later third-millennium trade routes traveled northeast from the Indus Valley toward Harappa and Kalibangan, south toward Lothal and the Arabian Sea, and north toward cities in Central Asia. Other later third-millennium trade routes traveled between the Baluchistan Mountains and the Indus Valley and near the coast of the Arabian Sea. Copper was scattered throughout the area, while shells were concentrated along the coast of the Arabian Sea; lapis lazuli and gold on the western edge of the Himalayan Mountains; and tin, turquoise, and gold along the Baluchistan Mountains at the map’s western edge.

MAP 2.5 | The Indus River Valley in the Third Millennium BCE

Historians know less about the urban society of the Indus Valley in the third millennium BCE than they do about its contemporaries in Mesopotamia and Egypt, in part because of the absence of a written record. Recent scholarship has suggested the importance of a second seasonal flow (as opposed to a year-round river) in the channel of the long-dried-up Ghaggar-Hakra to the east of the Indus.

- Where were cities concentrated in the Indus Valley? Why do you think the cities were located where they were?

- How do the trade routes of the fourth and early third millennium BCE differ from those of the later third millennium BCE? What might account for those differences?

- What commodities appear on this map? What is their relationship to urban centers and trade routes?

Whether along the year-round-flowing Indus or the seasonal flows of water in the Ghaggar-Hakra paleochannel, farmers planted wheat and barley, harvesting the crops the next spring. Harappan villagers also improved their tools of cultivation. Researchers have found evidence of furrows, probably made by plowing, that date to around 2600 BCE. These developments suggest that, as in Mesopotamia and Egypt, farmers were cultivating harvests that yielded a surplus that allowed many inhabitants to specialize in other activities. In time, rural wealth produced urban splendor. More abundant harvests, now stored in large granaries, brought migrants into the area and supported expanding populations. By 2500 BCE cities began to replace villages throughout the Indus River valley, and within a few generations towering granaries marked the urban skyline. Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, the two largest cities, each covered a little less than half a square mile and may have housed 35,000 residents.

Harappan cities sprawled across a vast floodplain covering 500,000 square miles—two or three times the size of the Mesopotamian cultural zone. At the height of their development, the Harappan peoples reached the edge of the Indus ecological system and encountered the cultures of northern Afghanistan, the inhabitants of the desert frontier, the nomadic hunters and gatherers to the east, and the traders to the west. Scholars know less about Harappan society than about Mesopotamia or ancient Egypt, since many of the remains of Harappan culture lie buried under deep silt deposits accumulated over thousands of years of heavy flooding. But what they do know about Harappan urban culture and trade routes is impressive.

Harappan City Life and Writing

The well-planned layout of Harappan cities and towns included a fortified citadel housing public facilities alongside a large residential area. The main street running through the city had covered drainage on both sides, with house gates and doors opening onto back alleys. Citadels were likely centers of political and ritual activities. At the center of the citadel of Mohenjo Daro was the famous great bath. The location, size, and quality of the bath’s steps, mortar and bitumen sealing, and drainage channel all suggest that the structure was used for public bathing rituals.

The Harappans used brick extensively—in upper-class houses, city walls, and underground water drainage systems. Workers used large ovens to manufacture the durable construction materials, which the Harappans laid so skillfully that basic structures remain intact to this day. A well-built house of a wealthier family had private bathrooms, showers, and toilets that drained into municipal sewers, also made of bricks. Houses in small towns and villages were made of less durable and less costly sun-baked bricks.

More information

A photo of the Mohenjo Daro ruins shows the layout of houses and sewer drainage systems. Layers of bricks form rectangular shapes and are arranged in an organized pattern with spaces between them. In the background is a narrow mound of dirt.

In terms of writing, the peoples of the Indus Valley developed a logographic system of writing made up of about 400 signs (far too many for an alphabetic system, which tends to have closer to thirty symbols). Without a bilingual or trilingual text, like the Behistun inscription for Sumerian cuneiform or the Rosetta Stone for Egyptian hieroglyphs, Indus Valley script has been impossible to decipher. Computer analysis, however, is helping researchers identify some features of the script and the pre-Indo-European language it might record. Even so, some scholars suggest that the signs might not represent spoken language, but rather might be a nonlinguistic symbol system. Although a ten-glyph-long public inscription has been found at the Harappan site of the ancient city of Dholavira, nearly all of what remains of the Indus Valley script is to be found on a thousand or more stamp seals and small plaques excavated from the region. These seals and plaques may represent the names and titles of individuals rather than complete sentences. As of yet, there is no evidence that the Harappans produced historical records such as the King Lists of Mesopotamia and Egypt, thus making it impossible to chart a history of the rise and fall of dynasties and kingdoms. Hence, our knowledge of Harappa comes exclusively from archaeological reconstructions, reminding us that “history” is not what happened but only what we know about what happened.

CORE OBJECTIVES

TRACE and EVALUATE the trade connections stretching from Mesopotamia to the Indus River valley societies.

Trade

The Harappans engaged in trade along the Indus River, through the mountain passes to the Iranian plateau, and along the coast of the Arabian Sea as far as the Persian Gulf and Mesopotamia. They traded copper, flint, shells, and ivory, as well as pottery, flint blades, and jewelry created by their craftworkers, in exchange for gold, silver, gemstones, and textiles. Trade was facilitated by standardized sets of weights and measures. Carnelian, a precious red stone, was a local resource, but lapis lazuli had to come from what is now northern Afghanistan. Some of the Harappan trading towns nestled in remote but strategically important places. Consider Lothal, a well-fortified port at the head of the Gulf of Khambhat (Cambay). Although distant from the center of Harappan society, it provided vital access to the sea and to valuable raw materials. Its many workshops processed precious stones, both local and foreign. Because the demand for gemstones and metals was high on the Iranian plateau and in Mesopotamia, control of their extraction and trade was essential to maintaining the Harappans’ economic power. So the Harappans built fortifications and settlements near sources of carnelian and copper mines.

Through a complex and vibrant trading system, the Harappans maintained access to mineral and agrarian resources. To facilitate trade, rulers relied not just on Harappan script but also on a system of weights and measures that they devised and standardized. Archaeologists have found Harappan seals, used to stamp commodities with the names of their owners or the nature of the goods, at sites as far away as the Persian Gulf, Mesopotamia, and the Iranian plateau.

The general uniformity in Harappan sites suggests a centralized and structured state. Unlike the Mesopotamians and the Egyptians, however, the Harappans apparently built neither palaces nor grand royal tombs. What the Indus River people show us is how much the urbanized parts of the world were diverging from one another, even as they borrowed from and imitated their neighbors.