THE BIG PICTURE

What was the relationship between climate change and human settlement patterns in the second millennium BCE?

THE BIG PICTURE

What was the relationship between climate change and human settlement patterns in the second millennium BCE?

Pastoral Nomads

At the end of the third millennium BCE, a changing climate, drought, and food shortages led to the overthrow of ruling elites throughout central and western Afro-Eurasia. Walled cities could not defend their hinterlands. Trade routes lay open to predators, and pillaging became a lucrative enterprise. Clans of horse-riding pastoral nomads—from the relatively sparsely populated and isolated Inner Eurasian steppes—swept across vast distances, eventually threatening settled people in cities. Transhumant herders—who lived closer to agricultural settlements and migrated seasonally to pasture their livestock—also advanced on populated areas in search of food and resources. These migrations of pastoral nomads and transhumant herders occurred across Eurasia, in the Arabian Desert and Iranian plateau in the west, and in the Indus River valley and the Yellow River valley in the east. (See Map 3.1.) Many transhumant herders and nomadic pastoralists settled in the agrarian heartlands of Mesopotamia, the Indus River valley, the highlands of Anatolia, Iran, China, and Europe. After the first wave of newcomers, more migrants arrived by foot or in wagons pulled by draft animals. Some sought temporary work; others settled permanently. They brought horses and new technologies that were useful in warfare; religious practices and languages; and new pressures to feed, house, and clothe an ever-growing population. This millennia-long process is sometimes referred to as Indo-European migrations.

The term Indo-European was created by comparative linguists to trace and explain the similarities within the large language family that includes Sanskrit, Hindi, Persian, Greek, Latin, and what would become German and English. Words and concepts that appear in many languages, such as numbering systems and words like mother, father, and god, suggest these so-called Indo-European languages may have had a common origin. For instance, the number one is eka (in Sanskrit), ek (in Hindi), hen (in Greek), unus (in Latin), un (in French), and ein (in German). The word for mother is mātr, (in Sanskrit), mātā (in Hindi), mêter (in Greek), mater (in Latin), mère (in French), and mutter (in German). A host of demographic, geographic, and other factors shape the movement and development of languages over time. Nonetheless, migrations of the earliest speakers of the Indo-European language group, who carried not only their language but also their technology and culture, are likely part of the story of the spread of pastoralists from the central Eurasian steppe into Europe, Anatolia, Southwest Asia, and South Asia.

Perhaps the most vital breakthroughs that nomadic pastoralists transmitted to settled societies were the harnessing of horses and the invention of the chariot, a horse-drawn vehicle with two spoked and metal-rimmed wheels, used in warfare and later in processions and races. The chariot revolution was made possible, however, only through the interactions of pastoralists and settled communities. On the vast steppe lands north of the Caucasus Mountains, during the late fourth millennium BCE, settled people had domesticated horses in their native habitat. The domestication of horses was a major breakthrough for humans. Horses could forage for themselves, even in snow-covered lands; hence they did not require humans to find food for them. Moreover, they could be ridden up to 30 miles a day. Elsewhere, as on the northern steppes of what is now Russia, horses were a food source. Only during the late third millennium BCE did people harness horses with cheek pieces and mouth bits in order to facilitate the control of horses and their use for transportation. Parts of horse harnesses made from wood, bone, bronze, and iron, found in tombs scattered across the steppe, reveal the evolution of headgear from simple mouth bits to full bridles with headpiece, mouthpiece, and reins.

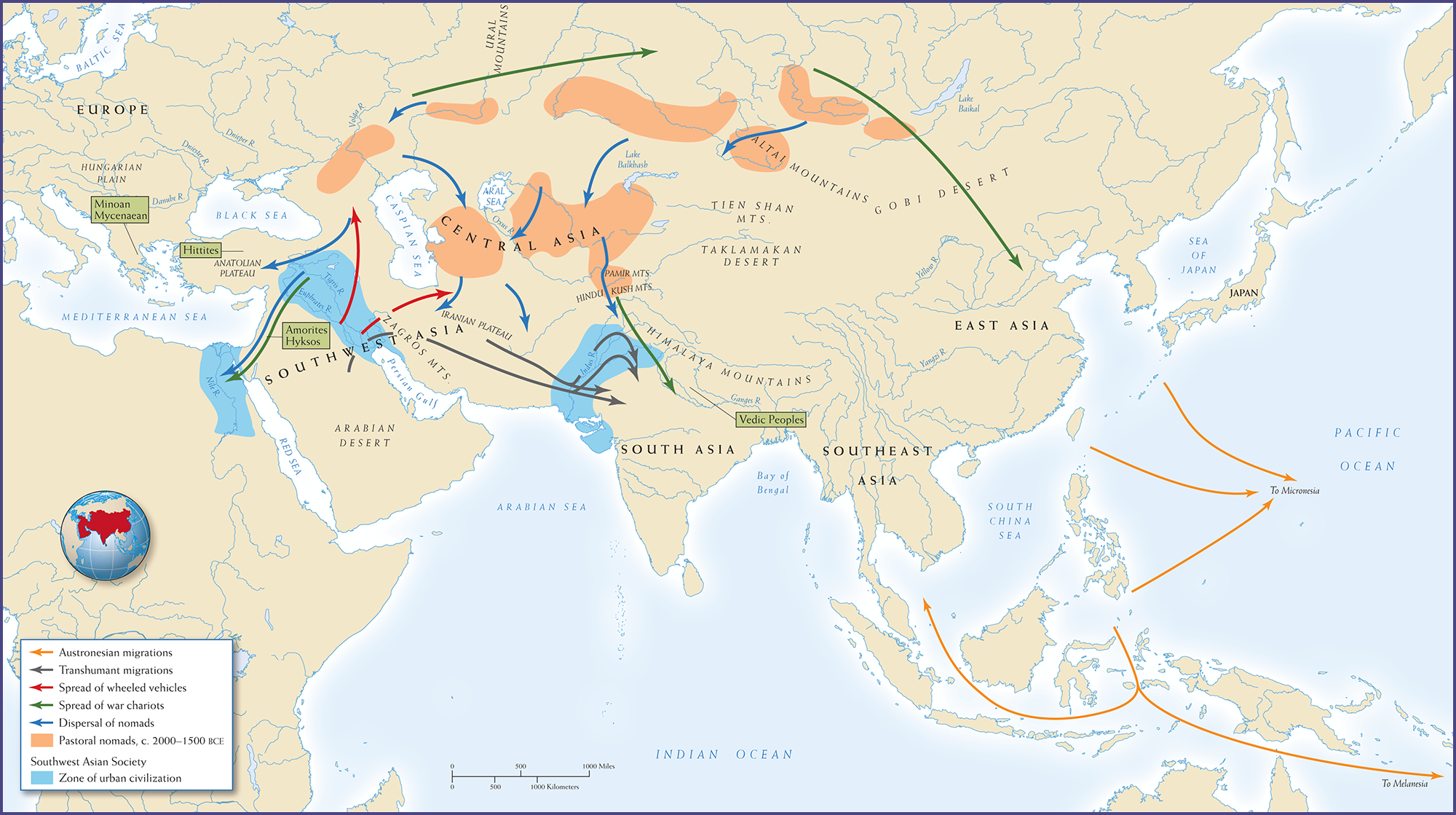

Map 3.1 is titled, “Nomadic Migrations in Afro-Eurasia, 2000-1000 B C E.” The location of pastoral nomads circa 2000-1500 B C E, the routes they used to disperse, the zones of urban civilization in Southwest Asia, transhumant migrations, and the spread of wheeled vehicles and war chariots are marked on the map. Pastoral nomads are located in the area around the Altai Mountains, as well as large stretches of Central Asia including the area around the Volga River, Caspian and the Aral Sea, and Hindu Kush Mountains. From there, they disperse within their already established regions, as well as west into Egypt and the Anatolian Plateau, south into the Iranian Plateau, and southeast towards the Indus River Valley zone of urban civilization. Transhumant herders travel eastward from the Arabian Desert and the Iranian Plateau into the Indus River Valley. War chariots travel from the Mesopotamian zone of urban civilization into the Nile’s River’s similar zone, as well as east across the Ural Mountains, south into India, and southeast across the Gobi desert and into East Asia. Meanwhile, wheeled vehicles spread north and east from Mesopotamia’s urban zone into Central Asia and the Iranian Plateau.

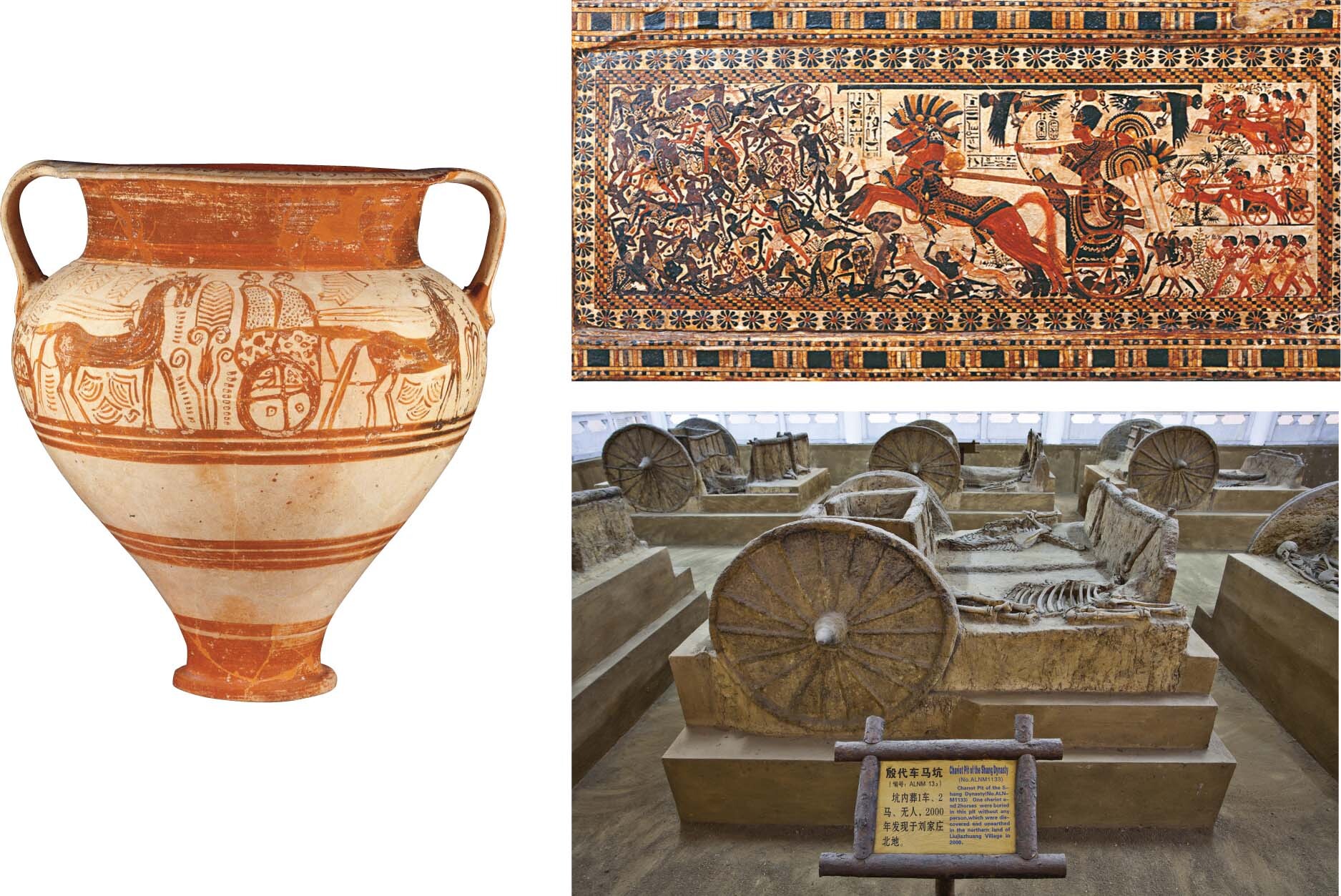

A large vase typical of Mycenaean art has banding and a horse-drawn chariot painted on it.

Chariots made of clay at a Chinese museum. There are two horse skeletons resting on top of each chariot.

A wooden chest with a painting of a pharaoh on a chariot fighting several people. The pharaoh and his horse-drawn chariot are painted much larger than the other people in the painting There are soldiers on foot and on horse-drawn chariots behind him. There is a large group of people fighting in front of him.

Sometime around 2000 BCE, pastoral nomads in the mountains of the Caucasus joined the bit-harnessed horse to the two-wheeled chariot. Various chariot innovations began to unfold: pastoralists lightened chariots so their warhorses could pull them faster; spoked wheels made of special wood bent into circular shapes replaced solid-wood wheels that were heavier and prone to shatter; wheel covers, axles, and bearings (all produced by settled people) were added to the chariots; and durable metal went into the chariot’s moving parts. Hooped bronze and, later, iron rims reinforced the spoked wheels. Initially iron was a decorative and experimental metal, and all tools and weapons were bronze. Iron’s hardness and flexibility, however, eventually made it more desirable for reinforcing moving parts and protecting wheels, like those on the chariot. Thus, the horse chariots combined innovations by both nomads and settled agriculturalists.

These innovations—combining engineering skills, metalworking, and animal domestication—revolutionized the way humans made war. The horse chariot slashed travel time between capitals. Slow-moving infantry now ceded to battalions of chariots. Each vehicle carried a driver and an archer and charged into battle with lethal precision and ravaging speed. The mobility, accuracy, and shooting power of warriors in horse-drawn chariots tilted the political balance. After the nomads perfected this type of warfare (by 1600 BCE), they challenged the political systems of Mesopotamia and Egypt, and chariots soon became central to the armies of Egypt, the Assyrians and Persians of Southwest Asia, the Vedic kings of South Asia, the later Zhou rulers in China, and local nobles as far west as Italy, Gaul, and Spain. Only with the development of cheaper armor made of iron (after 1000 BCE) did foot soldiers recover their military importance. And only after states developed cavalry units of horse-mounted warriors did chariots lose their decisive military advantage. For much of the second millennium BCE, then, charioteer elites prevailed in Afro-Eurasia.

For city dwellers in the river basins, the first sight of horse-drawn chariots must have been terrifying, but they quickly understood that war making had changed and they scrambled to adapt. The pharaohs in Egypt probably copied chariots from nomads or neighbors, and they came to value them highly. For example, the young pharaoh Tutankhamun (r. c. 1336–1327 BCE) was a chariot archer who made sure his war vehicle and other gear accompanied him in his tomb. A century later, the Shang kings of the Yellow River valley, in the heartland of agricultural China, likewise were entombed with their horse chariots.

While nomads and transhumant herders toppled the river-basin cities in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China through innovations in warfare such as the chariot, the turmoil that ensued sowed seeds for a new type of regime: the territorial state. Even as Sargon and the Akkadians set up a short-lived territorial state in earlier Mesopotamia (2334–2200 BCE) (see Chapter 2), the martial innovations and political and environmental crises of the early second millennium BCE helped spur more enduring development of territorial states elsewhere. The territorial state was a centralized kingdom organized around a charismatic ruler. The new rulers of these territorial states exerted power not only over localized city-states but also over distant hinterlands. They enhanced their stability through rituals for passing the torch of command from one generation to the next. People no longer identified themselves as residents of cities; instead, they felt allegiance to large territories, rulers, and broad linguistic and ethnic communities. These territories for the first time had identifiable borders, and their residents felt a shared identity. Territorial states differed from the city-states that preceded them in that the new territorial states in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China based their authority on monarchs, widespread bureaucracies, elaborate legal codes, large territorial expanses, definable borders, and ambitions for continuous expansion.

The three great river-basin societies discussed in Chapter 2—Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley—collapsed at around the same time. The collapse in Egypt and Mesopotamia was almost simultaneous (roughly between 2200 BCE and 2100 BCE). In contrast, while the collapse was delayed in the Indus Valley for approximately 200 years, when it came, it virtually wiped out the Harappan state and culture. At first, historians focused on political, economic, and social causes, stressing bad rulers, nomadic incursions, political infighting, population migrations, and the decline of long-distance trade. In more recent times, however, a group of scientists that includes paleobiologists, climatologists, sedimentationists, and archaeologists has studied these societies and found convincing evidence that a truly radical change in the climate—a 200-year-long drought spreading across the Afro-Eurasian landmass—was a powerful factor in the collapse of these cultures. But how can these researchers know so much about the climate 4,000 years ago? The table assembles the evidence for their assertions, drawing on their scholarly studies of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley.

|

River-Basin Society |

Date of Collapse |

Climatological Evidence |

Archaeological Evidence |

Literary Evidence |

|

Egypt |

The Old Kingdom collapsed and ushered in a period of notable political instability, the First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BCE). |

Sedimentation studies reveal markedly lower Nile floods and an invasion of sand dunes into cultivated areas. |

Many of the sacred sites of the Old Kingdom and much of their artwork are believed to have been destroyed in this period due to political chaos. |

An abundant literary record is full of tales of woe. Poetry and stelae call attention to famine, starvation, low Nile floods, and even cannibalism. |

|

Mesopotamia |

The last effective ruler of the Kingdom of Akkad (2334–2193 BCE) was Naram Sin (r. 2254–2218 BCE). |

Around 2100 BCE, inhabitants abruptly abandoned the Khabur drainage basin, whose soil samples reveal marked aridity as determined by the existence of fewer earthworm holes and wind-blown pellets. |

Tell Leilan and other sites indicate that the large cities of this region began to shrink around 2200 BCE and were soon abandoned and remained unoccupied for 300 years. |

Later Ur III scribes described the influx of northern “barbarians” and noted the construction of a wall, known as the Repeller of the Amorites, to keep these northerners out. |

|

Indus Valley and the Harappan society |

Many of the Harappan peoples migrated eastward, beginning around 1900 BCE, leaving this region largely empty of people. |

Hydroclimatic reconstructions show that precipitation began to decrease around 3000 BCE, reaching a low in 2000 BCE, at which point the Himalayan rivers stopped incising. Around 1700 BCE, the Ghaggar-Hakra rivers dried up. |

Major Harappan urban sites began to shrink in size and lose their urban character between 1900 and 1700 BCE. |

There is no literary source material because the Harappan script has still to be deciphered. |

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

Behringer, Wolfgang, A Cultural History of Climate (2010).

Bell, Barbara, “The Dark Ages in Ancient History,” American Journal of Archaeology 75 (January 1971): 1–26.

Butzer, Karl W., “Collapse, Environment, and Society,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 109 (March 2012): 3632–39.

Cullen, H. M., et al., “Climate Change and the Collapse of the Akkadian Empire,” Geology 28 (April 2000): 379–82.

Giosan, Liviu, et al., “Fluvial Landscapes of the Harappan Civilization,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 109 (June 2012): E1688–94.

Weiss, Max, et al., “The Genesis and Collapse of Third Millennium North Mesopotamian Civilization,” Science, New Series, 261 (August 20, 1993): 995–1004.