The Territorial State in Egypt

The first of the great territorial states of this period arose from the ashes of chaos in Egypt. The long era of prosperity associated with Old Kingdom Egypt ended when drought brought catastrophe to the area. For several decades the Nile did not overflow its banks, and Egyptian harvests withered. (See Current Trends in World History: Climate Change and the Collapse of River-Basin Societies.) As the pharaohs lost legitimacy and fell prey to feuding among rivals for the throne, regional elites replaced the authority of the centralized state. Egypt, which had been one of the most stable corners of Afro-Eurasia, endured more than a century of tumult before a new order emerged. The pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom and, later, the New Kingdom reunified the river valley and expanded south and north.

Religion and Trade in Middle Kingdom Egypt (2055–1650 BCE)

Around 2050 BCE, after a century of drought, the Nile’s floodwaters returned to normal and crops grew again. In the centuries that followed, pharaohs at Thebes consolidated power in Upper Egypt and began new state-building activity, ushering in a new phase of stability that historians call the Middle Kingdom. The rulers of this era developed Egypt’s religious and political institutions in ways that increased state power, creating the conditions for greater prosperity and trade.

RELIGION AND RULE Spiritual and worldly powers once again reinforced each other in Egypt. Gods and rulers together replaced the chaos that people believed had brought drought and despair. Amenemhet I (1985–1955 BCE), first pharaoh of the long-lasting Twelfth Dynasty (1985–1795 BCE), elevated a formerly less significant god, Amun, to prominence. The king capitalized on the god’s name, which means “hidden,” to convey a sense of his own invisible omnipresence throughout the realm. Because Amun’s attributes of air and breath were largely intangible, believers in other gods were able to embrace his cult. Amun’s cosmic power appealed to people in areas that had recently been impoverished.

The pharaoh’s elevation of the cult of Amun unified the kingdom and brought even more power to Amun and the pharaoh. Consequently, Amun eclipsed all the other gods of Thebes. Merging with the formerly omnipotent sun god Re, the deity now was called Amun-Re: the king of the gods. Because the power of the gods and kings was intertwined, the pharaoh as Amun’s earthly champion enjoyed enhanced legitimacy as the supreme ruler.

More information

The inscribed columns of the Great Hypostyle Hall, built by Ramses 2 in the thirteenth century B C E.

The massive temple complex dedicated to Amun-Re offers evidence of the gods’ and the pharaoh’s joint power. Middle Kingdom rulers tapped into their kingdom’s renewed bounty, their subjects’ loyalty, and the work of untold commoners and enslaved peoples to build Amun-Re’s temple complex at Thebes (present-day Luxor). For more than 12,000 years, Egyptians and the people they enslaved toiled to erect monumental gates, enormous courtyards, and other structures in what was arguably the largest, longest-lasting public works project ever undertaken. Blending the pastoral ideals of herders into the institutions of their settled and hierarchical territorial state, Middle Kingdom rulers also nurtured a cult of the pharaoh as the good shepherd whose prime responsibility was to care for his human flock. In a building inscription at Heliopolis, a pharaoh named Senusret III from the nineteenth century BCE claims to have been appointed by Amun as “shepherd of the land.” And 500 years later, in the fourteenth century BCE, Amenhotep III’s building inscription at Karnak describes him as “the good shepherd for all people.” By instituting charities, offering homage to gods at the palace to ensure regular floodwaters, and performing ceremonies to honor their own generosity, the pharaohs portrayed themselves as these shepherds. In these inscriptions and in imagery (recall, in Chapter 2, the shepherd’s crook as one of the pharaoh’s symbols), pharaohs exploited distinctly pastoralist symbolism. As a result, the cult of Amun-Re was both a tool of political power and a source of spiritual meaning for the different peoples of the blended territorial state of Egypt.

More information

An ancient Egyptian chest amulet. Different symbolism used in the amulet is as follows: The amulet has the disk and crescent of the moon with Tutankhamun flanked by the moon god and the sun god, The eye of Horus, The golden boat on the moon, The scarab, symbol of the sun god, The falcon, symbol of the sun god, The cobra, symbol of Wadjet, a lotus flower, The sun disk and the symbol of infinity.

MERCHANTS AND EXPANDING TRADE NETWORKS Prosperity gave rise to an urban class of merchants and professionals who used their wealth and skills to carve out new opportunities for themselves. They indulged in leisure activities such as formal banquets with professional dancers and singers, and they honed their skills in hunting, fowling, and fishing. In a sign of their upward mobility and autonomy, some members of the middle class constructed tombs filled with representations of the material goods they would use in the afterlife as well as the occupations that would engage them for eternity. This new merchant class did not rely on the king’s generosity and took burial privileges formerly reserved for the royal family and a few powerful nobles.

As they centralized power and consolidated their territorial state, Egyptians also expanded their trade networks. (See Map 3.2.) Because the floodplains had long since been deforested, the Egyptians needed to import massive quantities of wood by ship. Most prized were the cedars from Byblos (a city in the land soon known as Phoenicia, roughly present-day Lebanon), which were crafted into furniture and coffins. Commercial networks extended south through the Red Sea to present-day Ethiopia and were used to import precious metals, ivory, livestock, and exotic animals such as panthers and monkeys. They brought enslaved people as well. Expeditions to the Sinai Peninsula searched for copper and turquoise. Egyptians looked south for gold, which they prized for personal and architectural ornamentation. To acquire it, they crossed into Nubia, where they met stiff resistance. One Egyptian official from the reign of Amenemhet II (the third pharaoh of the long-lasting Twelfth Dynasty) bragged about his expeditions into the Sinai and south into Nubia: “I forced the (Nubian) chiefs to wash gold. . . . I went overthrowing by the fear of the Lord of the Two Lands [i.e., the pharaoh].” Eventually, the Egyptians colonized Nubia to broaden their trade routes and secure these coveted resources. As part of Egyptian colonization southward, a series of forts extended as far south as the second cataract of the Nile River (just south of the modern-day border between Egypt and Sudan).

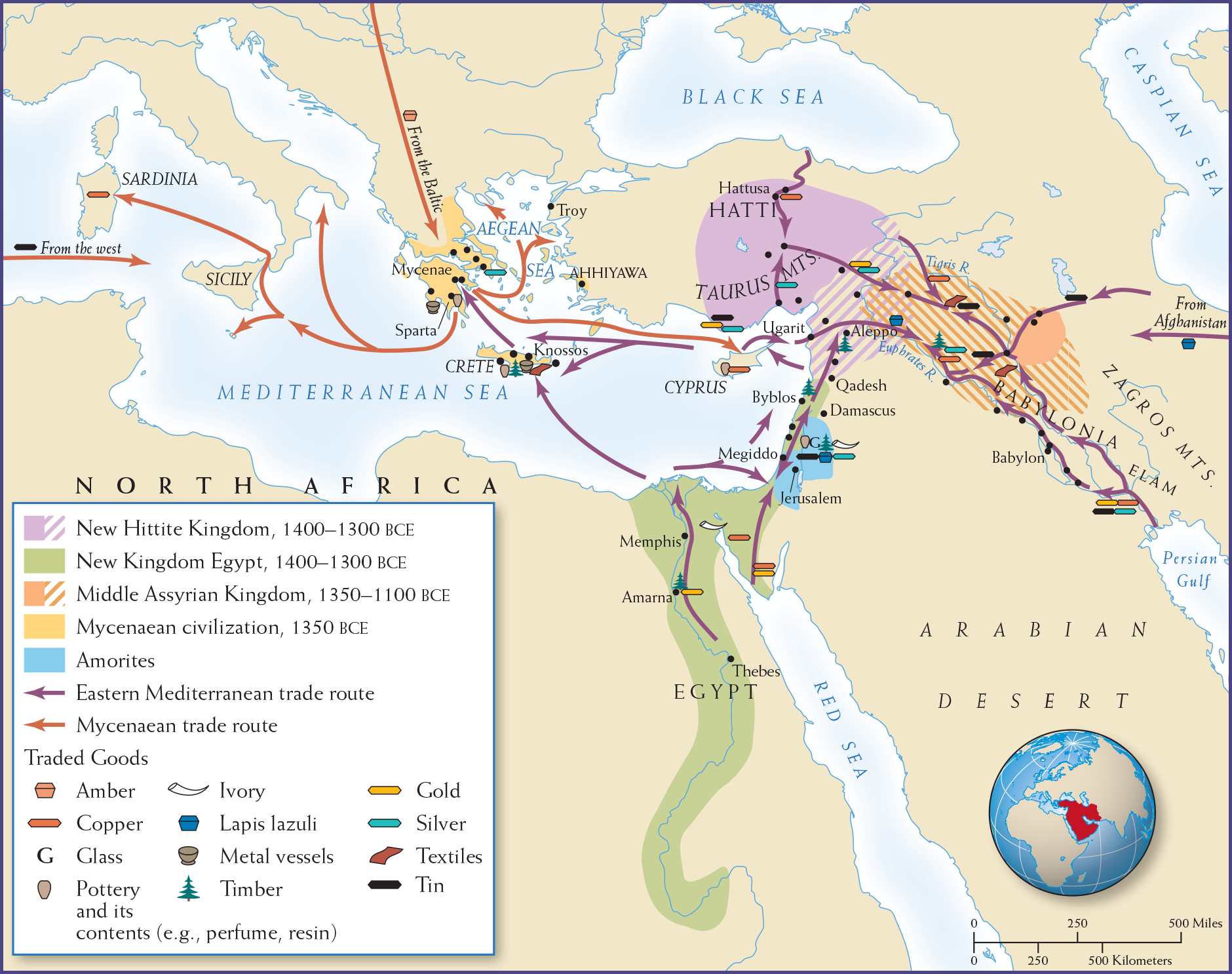

More information

Map 3.2 is titled, Territorial States and Trade Routes in Southwest Asia, North Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean, 1500-1350 B C E. Following are the boundaries of four major trading states marked on the map: the Amorites (the area around Jerusalem); Mycenaean civilization (the southern part of mainland Greece and Crete, 1350 B C E); New Kingdom Egypt (along the Nile, 1400-1300 BCE); New Hittite Kingdom (the eastern part of Turkey into Syria, 1400-1300 B C E); and Middle Assyrian Kingdom (Babylonia, 1350-1100 B C E). Major cities shown on the map include Babylon, Thebes, Amarna, Memphis, Jerusalem, Megiddo, Byblos, Qadesh, Aleppo, Ugarit, Kizzuwatna, Ahhiyawa, Damascus, Troy, Knossos, and Sparta. Trade routes extending from Greece out in every direction are shown, as are the routes that connected the Eastern Mediterranean and the trading states mentioned above. Traded goods include timber, metal vessels, pottery and its contents (example. perfume, resin), textiles, gold, tin, copper, glass, ivory, lapis lazuli, and silver.

MAP 3.2 | Territorial States and Trade Routes in Southwest Asia, North Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean, 1500–1350 BCE

Trade in many commodities brought the societies of the Mediterranean Sea and Southwest Asia into increasingly closer contact.

- What were the major trade routes and the major trading states in Southwest Asia, North Africa, and the eastern Mediterranean during this time?

- What were the major trade goods? Which regions appear to have had more, and more unique, resources than the others?

- What did each region need from the others? What did each region have to offer in exchange for the goods it needed?

Migrations and Expanding Frontiers in New Kingdom Egypt (1550–1070 BCE)

The success of the new commercial networks lured pastoral nomads who were searching for work. Later, chariot-driving Hyksos invaders from Southwest Asia attacked Egypt, setting in motion the events marking the break between what historians call the Middle and New Kingdoms of Egypt. Although the invaders challenged the Middle Kingdom, they also inspired innovations that enabled the New Kingdom to thrive and expand.

HYKSOS INVADERS Sometime around 1640 BCE, a western Semitic-speaking people, whom the Egyptians called the Hyksos (“Rulers of Foreign Lands”), overthrew the unstable Thirteenth Dynasty (toward the end of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom period). The Hyksos had mastered the art of horse chariots. Thundering into battle with their war chariots and their superior bronze axes and composite bows (made of wood, horn, and sinew), they easily defeated the pharaoh’s foot soldiers. The victorious Hyksos did not destroy the conquered land, but adopted and reinforced Egyptian ways. Ruling as the Fifteenth Dynasty, the Hyksos asserted control over the northern part of the country and transformed the Egyptian military.

After a century of political conflict, an Egyptian who ruled the southern part of the country, Ahmosis (r. 1550–1525 BCE), successfully used the Hyksos weaponry—horse chariots—against the invaders themselves and became pharaoh. This conquest marked the beginning of what historians call New Kingdom Egypt. Hyksos invasions had taught Egyptian rulers that they must vigilantly monitor their frontiers, for they could no longer rely on deserts as buffers. Ahmosis assembled large, mobile armies and drove the Hyksos “foreigners” back. Diplomats followed in the army’s path, as the pharaoh initiated a strategy of interference in the affairs of Southwest Asian states. Such policies laid the groundwork for statecraft and an international diplomatic system that future Egyptian kings used to dominate the eastern Mediterranean world.

Migrations and invasions introduced new techniques that the Egyptians adopted to consolidate their power. These included bronze working (which the Egyptians had not perfected), an improved potter’s wheel, and a vertical loom. South Asian animals such as humped zebu cattle, as well as vegetable and fruit crops, now appeared on the banks of the Nile for the first time. Other significant innovations pertained to war, such as the horse and chariot, the composite bow, the scimitar (a sword with a curved blade), and other weapons from western Eurasia. These weapons transformed the Egyptian army from a standing infantry to a high-speed, mobile, and deadly fighting force. Egyptian troops extended the military frontier as far south as the fourth cataract of the Nile River (in northern modern-day Sudan), and the kingdom now stretched from the Mediterranean shores to Ethiopia.

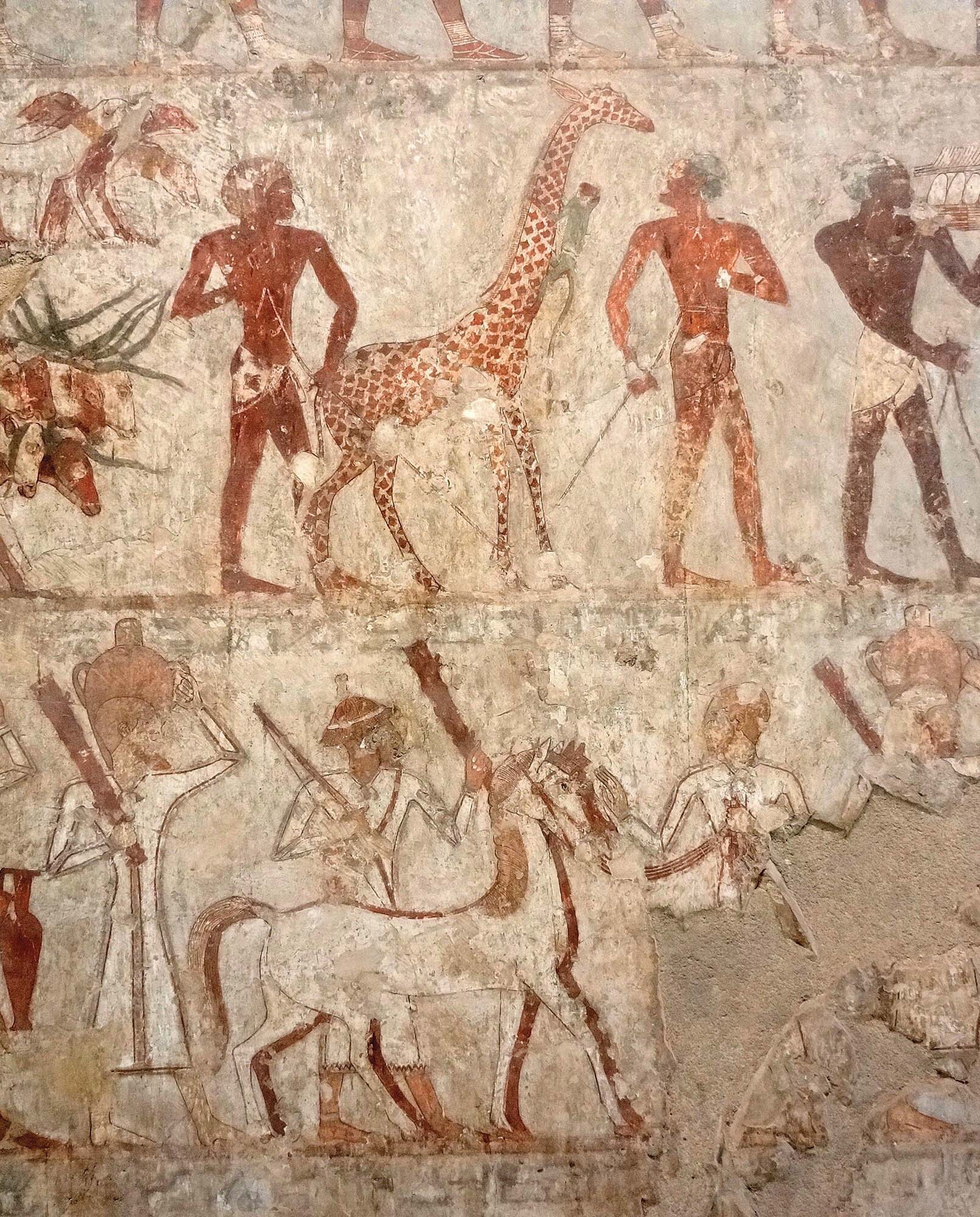

EXPANDING FRONTIERS By the beginning of the New Kingdom, the territorial state of Egypt was projecting its interests outward: it defined itself as a superior, cosmopolitan society with an efficient bureaucracy run by competent and socially mobile individuals. Paintings on the walls of Vizier Rekhmire’s tomb from the mid-fifteenth century BCE record the wide-ranging tribute from distant lands that he received on behalf of the pharaoh, including a veritable menagerie: cattle, a giraffe, an elephant, a panther, baboons, and monkeys. The collected taxes that are enumerated in the accompanying inscriptions included offerings of gold, silver, linen, bows, grain, and honey. Rekhmire’s tomb, with its paintings, tax lists, and instructions for how to rule, offers a prime example of how the bureaucracy managed the expanding Egyptian frontiers. Pushing the transnational connectivity even further, it has been argued that inscriptions and paintings from Rekhmire’s tomb, together with other tomb paintings, show that Keftiu (people from Minoan Crete), along with Hittites from Asia Minor, Syrians from the Levant, and Nubians from the south, may have gathered for some major multinational event in Egypt, like a Sed festival.

More information

A painting of the parade of foreign peoples. People present annual tributes and gifts to king Thutmosis 3 in the presence of Vizier Rekhmire. The gifts include crafts, vessels of gold and silver, animals like dogs, oxen with curved horns, a baboon, giraffe, feline, baby elephant, a bear, and horses. They also present elephant tusks, a chariot, and vases, some of which are gold.

More information

A bust of Queen Hatshepsut wearing a masculine headdress and kilt.

A bust of Queen Hatshepsut as masculine portrayal.

As mentioned above, Egypt expanded its control southward into Nubia, as a source of gold, exotic raw materials, and manpower. Historians identify this southward expansion most strongly with the reign of Egypt’s most powerful woman ruler, Hatshepsut. She served as regent for her young stepson, Thutmosis III, who came to the throne in 1479 BCE when his father—Hatshepsut’s half brother and husband—Thutmosis II died. When her stepson was seven years old, Hatshepsut proclaimed herself “king,” ruling as co-regent until she died two decades later. During her reign there was little military activity, but trade contacts into the Levant and Mediterranean and southward into Nubia flourished. When he ultimately came to power, Thutmosis III (r. 1479–1425 BCE) launched another expansionist phase, northeastward into the Levant. The famed Battle of Megiddo, the first recorded chariot battle in history, took place twenty-three years into his reign. Thutmosis III’s army at Megiddo, including nearly 1,000 war chariots, defeated his adversaries and established an Egyptian presence in Palestine. The growth phase launched by Thutmosis III would continue for 200 years. Having evolved into a strong, expanding territorial state, Egypt was now poised to engage in commercial, political, and cultural exchanges with the rest of the region.

Glossary

- Hyksos

- Chariot-driving, axe- and composite-bow-wielding, Semitic-speaking people (their name means “rulers of foreign lands”), who invaded Egypt, overthrew the Thirteenth Dynasty, set up their own rule over Egypt, and were expelled by Ahmosis to begin the period known as New Kingdom Egypt.