CORE OBJECTIVES

COMPARE state formation in Shang China and in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The Shang Territorial State in East Asia

China’s first major territorial state combined features of earlier Longshan culture with new technologies and religious practices. Climate change affected East Asia much as it had central and Southwest Asia. Stories written on bamboo strips and later collected into what historians call the “Bamboo Annals” tell of a time at the end of the legendary Xia dynasty when the sun dimmed and frost and ice appeared in the summer, followed by heavy rainfall, flooding, and then a long drought. According to Chinese mythology, the first ruler of the Shang dynasty defeated a despotic Xia king and then offered to sacrifice himself so that the drought would end. This leader, Tang, survived to found the territorial state called Shang around 1600 BCE in northeastern China.

The Shang state was built on four elements that the Longshan peoples had already introduced: a metal industry based on copper; pottery making; walled towns; and divination using animal bones. To these Longshan foundations, the Shang dynasty added hereditary rulers whose power derived from their relation to ancestors and gods; written records; large-scale metallurgy (especially in bronze); tribute; and various rituals.

State Formation

A combination of these preexisting Longshan strengths and Shang innovations produced a strong Shang territorial state and a wealthy and powerful elite, noted for its intellectual achievements and aesthetic sensibilities.

More information

A bronze ceremonial drinking vessel shaped like a bird with elaborate carvings up and down its body.

Shang kings used a personalized style of rule, making regular trips around the country to meet, hunt, and conduct military campaigns. With no rival territorial states on its immediate periphery, the Shang state did not create a strongly defended, permanent capital, but rather moved its capital as the frontier expanded and contracted. Bureaucrats used written records to oversee the large and expanding population of the Shang state.

Advanced Shang metalworking—the beginnings of which appeared in northwestern China at pre-Shang sites dating as early as 1800 BCE—was vital to the Shang territorial state. Shang bronze work included weapons, fittings for chariots, and ritual vessels. Because copper and tin were available from the North China plain, only short-distance trade was necessary to obtain the resources that a bronze culture needed. (See Map 3.4.) Shang bronze-working technique involved the use of hollow clay molds to hold the molten metal alloy, which, when removed after the liquid had cooled and solidified, produced firm bronze objects. The casting of modular components that artisans could assemble later promoted increased production and permitted the elite to make extravagant use of bronze vessels for burials. The bronze industry of this period shows the high level not only of material culture (in the practical function of the physical objects) but also of cultural development (in the aesthetic sense of beauty and taste conveyed by the choice of form). Since Shang metalworking required extensive mining, it necessitated a large labor force, efficient casting, and a reproducible artistic style. Although the Shang state highly valued its artisans, it treated its copper miners as lowly tribute laborers. By controlling access to tin and copper and to the production of bronze, Shang kings prevented their rivals from forging bronze weapons and thus increased their own power and legitimacy. With their superior weapons, Shang armies by 1300 BCE could easily destroy armies wielding wooden clubs and stone-tipped spears.

Chariots entered the Central Plains of China with nomads of the north around 1200 BCE, much later than their appearance in Egypt and Southwest Asia. They were quickly adopted by the upper classes. Chinese chariots were larger (fitting three men standing in a box mounted on eighteen- or twenty-six-spoke wheels) and much better built than those of their neighbors. As symbols of power and wealth, they were often buried with their owners. Yet, unlike elsewhere in Afro-Eurasia, they were at first little used in warfare during the Shang era, perhaps because of the effectiveness and shock value of large Shang infantry forces, composed mainly of foot soldiers armed with axes, spears, arrowheads, shields, and helmets, all made of bronze. In Shang China, the chariot was used primarily for hunting and as a mark of high status. Shang metalworking and the incorporation of the chariot gave the Shang state a huge advantage and unprecedented power over its neighbors.

Agriculture and Tribute

The Shang dynastic rulers also understood the importance of agriculture for winning and maintaining power, so they did much to promote its development. The activities of local governors and the masses revolved around agriculture. Rulers controlled their own farms, which supplied food to the royal family, craftworkers, and the army. Farmers drained low-lying fields and cleared forested areas to expand the cultivation of millet, wheat, barley, and possibly rice. Their tools included stone plows, spades, and sickles. Farmers also cultivated silkworms and raised pigs, dogs, sheep, and oxen. Thanks to the twelve-month, 360-day lunar calendar developed by Shang astrologers, farmers were better able to track the growing season. By including leap months, this calendar maintained the proper relationship between months and seasons, and it relieved fears about solar and lunar eclipses by making them predictable.

More information

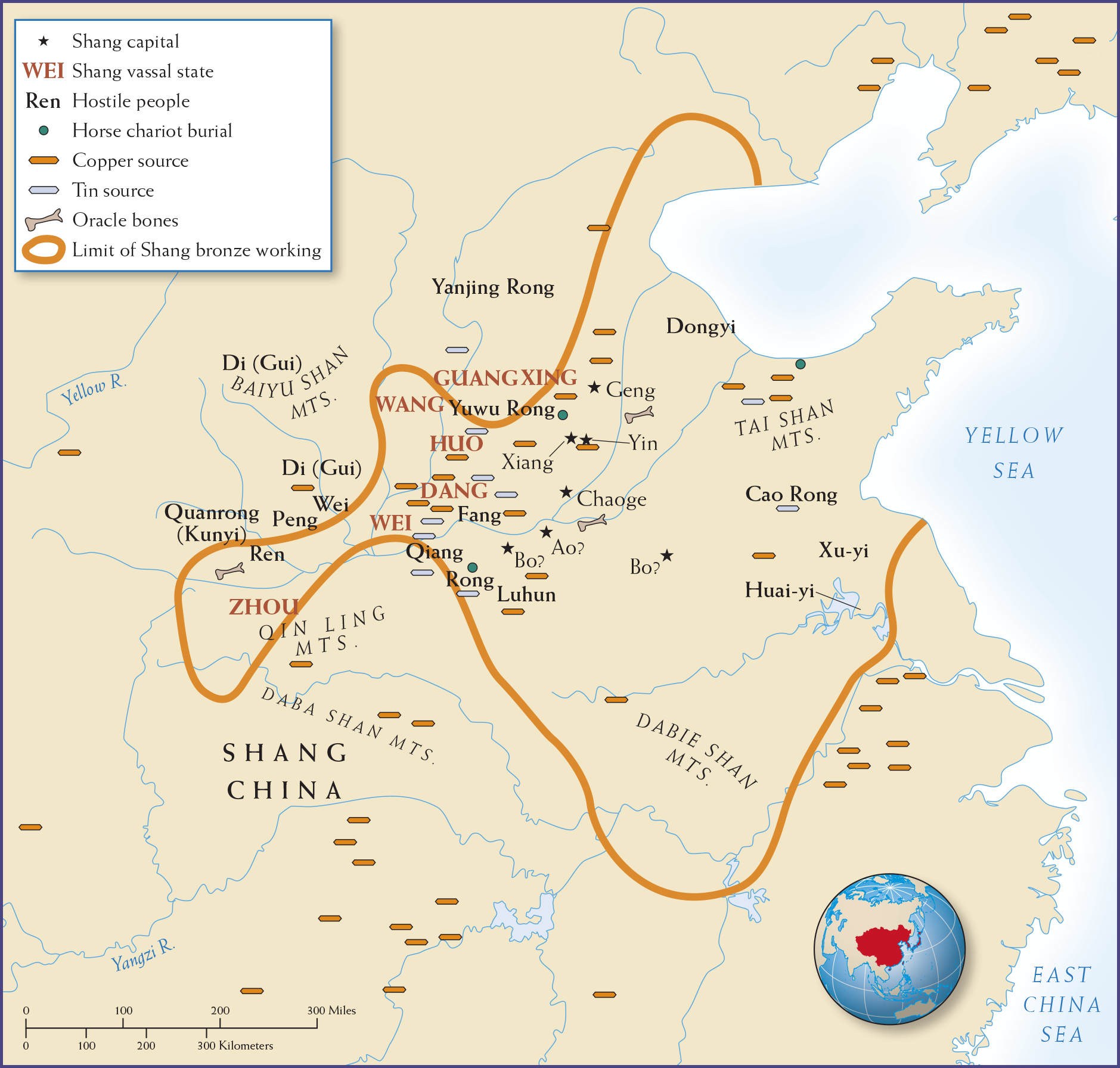

Map 3.4 is titled, “Shang Dynasty in East Asia.” The extent of China’s first major territorial state is depicted on the map by the limits of Shang bronze working (an irregular shape roughly covering the area between the Yellow and Yangzi Rivers, west of the Yellow Sea, and east of the Dabie Shan, Daba Shan, and Baiyu Shan Mountains. The map also shows Shang capitals (Bo, Ao, Xiang, Yin, Chaoge, and Geng), vassal states (Zhou, Wei, Dang, Huo, Wang, Guangxing), hostile people (Ren, Peng, Quanrong, Wei, Di, Yanjing Rong, Fang, Qiang, Rong, Lubun, Cao Rong, Xu-Yi, Huai-yi, and Dongyi); horse chariot burial (Rong and Yuwu Rong), oracle bones (near Geng and Ao), and copper and tin sources, which are clustered throughout Shang territory, and, in the case of copper, also further south, southeast, and northeast.

MAP 3.4 | Shang Dynasty in East Asia

The Shang state was one of the most important and powerful of early Chinese dynasties.

- Based on your analysis of this map, what raw materials were the most important to the Shang state?

- How were the deposits of these raw materials distributed across Shang territory and beyond? How might that distribution have shaped the area marked on the map as the limit of Shang bronze working?

- Locate the various Shang capitals. Why do you think they were located where they were?

The ruler’s wealth and power depended on tribute from elites and allies. Elites supplied warriors and laborers, horses and cattle. Allies sent foodstuffs, soldiers, and workers and assisted in the king’s affairs—perhaps by hunting, burning brush, or clearing land—in return for his help in defending against invaders and making predictions about the harvest. Commoners sent their tribute to the elites, who held the land as grants from the king. Farmers transferred their surplus crops to the elite landholders (or to the ruler if they worked on his personal landholdings) on a regular schedule. Tribute could also take the form of turtle shells and cattle scapulas (shoulder blades), which the Shang used for divination by means of oracle bones. Divining the future was a powerful way to legitimate royal power—and then to justify the right to collect more tribute. By placing themselves symbolically and literally at the center of all exchanges, the Shang kings reinforced their power over others.

Society and Ritual Practice

The advances in metalworking and agriculture gave the state the resources to sustain a complex society, in which religion and rituals reinforced the social hierarchy. The core organizing principle of Shang society was familial descent traced back many generations to a common male ancestor. Grandparents, parents, sons, and daughters lived and worked together and held property in common, but male family elders took precedence. Women from other male family lines married into the family and won honor when they became mothers, particularly of sons.

The death ritual, which involved sacrificing humans to join the deceased in the next life, reflected the importance of family, male dominance, and social hierarchy. Members of the royal elite were often buried with their full entourage, including wives, consorts, servants, chariots, horses, and drivers. The inclusion of personal servants and people enslaved by the elite among those sacrificed indicates a belief that the familiar social hierarchy would continue in the afterlife. An impressive example of the burial practices of the Shang elite is the tomb of an exceptional prominent woman, Fu Hao (also known as Fu Zi), who was consort to the king, a military leader in her own right, and a ritual specialist. She was buried with a wide range of objects made from bronze and jade (including weapons), ivory, pottery, cowrie shells that were used as currency, and a large cache of oracle bones, as well as six dogs and sixteen humans who appear to have been sacrificed to accompany her at death.

The Shang state was a full-fledged theocracy: it claimed that the ruler at the top of the hierarchy derived his authority through guidance from ancestors and gods. Shang rulers practiced ancestral worship, which was the major form of religious belief in China during this period. Ancestor worship involved performing rituals in which the rulers offered drink and food to their recently dead ancestors with the hope that they would intervene with their more powerful long-dead ancestors on behalf of the living. Divination was the process by which Shang rulers communicated with ancestors and foretold the future by means of oracle bones. Diviners applied intense heat to the shoulder bones of cattle or to turtle shells and interpreted the cracks that appeared on these objects as auspicious or inauspicious signs from the ancestors regarding royal plans and actions. On these so-called oracle bones, scribes subsequently inscribed the queries asked of the ancestors to confirm the diviners’ interpretations. Thus, Shang writing began as a dramatic ritual performance in which the living responded to their ancestors’ oracular signs.

More information

A bronze mask with exaggerated features.

The oracle bones and tortoise shells offer a window into the concerns and beliefs of the elite groups of these very distant cultures. The questions put to diviners most frequently as they inspected bones and shells involved the weather—hardly surprising in communities so dependent on growing seasons and good harvests—and family health and well-being, especially the prospects of having male children, who would extend the family line.

In Shang theocracy, because the ruler was the head of a unified clergy and embodied both religious and political power, no independent priesthood emerged. Diviners and scribes were subordinate to the ruler and the royal pantheon of ancestors he represented. Ancestor worship sanctified Shang control and legitimized the rulers’ lineage, ensuring that the ruling family kept all political and religious power. Because the Shang gods were ancestral deities, the rulers were deified when they died and ranked in descending chronological order. Becoming gods at death, Shang rulers united the world of the living with the world of the dead.

Shang Writing

As scribes and priests used their script on oracle bones for the Shang kings, the formal character-based writing of East Asia developed over time. So although Shang scholars did not invent writing in East Asia, they perfected it. Evidence for writing in this era comes entirely from oracle bones, which were central to political and religious authority under the Shang. Other written records may have been on materials that did not survive. This accident of preservation may explain the major differences between the ancient texts in China (primarily divinations on bones) and in the Southwest Asian societies that impressed cuneiform on clay tablets (primarily for economic transactions, literary and religious documents, and historical records). In comparison with the development of writing in Mesopotamia and Egypt, the transition of Shang writing from record keeping (for example, questions to ancestors, lineages of rulers, or economic transactions) to literature (for example, myths about the founding of states) was slower. Shang rulers initially monopolized writing through their scribes, who positioned the royal families at the top of the social and political hierarchy. And priests wrote on the oracle bones to address the otherworld and gain information about the future so that the ruling family would remain at the center of the political system.

As Shang China cultivated developments in agriculture, ornate bronze metalworking, and divinatory writing on oracle bones, the state did not face the repeated waves of pastoral nomadic invaders seen in other parts of Afro-Eurasia. It was nonetheless influenced by the chariot culture that eventually filtered into East Asia. Given that so many of the developments in Shang China bolstered the authority of the dynastic rulers and elite, it is perhaps not surprising that the chariot in China was initially more a marker of elite status than an effective tool for warfare. Our understanding of this period has been further complicated in recent decades with the spectacular bronze finds at the Sanxingdui site in the Sichuan region, which reveal the existence of another major bronze metallurgy culture in the Ancient Kingdom of Shu (c. 2050–1250 BCE).

Glossary

- oracle bones

- Animal bones inscribed, heated, and interpreted by Shang ritual specialists to determine the will of the ancestors.