Contact Between China and Rome

CORE OBJECTIVES

DESCRIBE the development of the Han dynasty from its beginnings through the third century CE.

The Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE)

The Han dynasty oversaw an unprecedented blossoming of peace and prosperity in East Asia. Although supporters of the Han dynasty boasted of the regime’s imperial uniqueness, in reality it owed much to its predecessor, the Qin state, which contributed vital elements of political unity and economic growth to its more powerful successor regime. (See Map 7.1.) Together, the Qin and Han created the political, social, economic, and cultural foundations that characterized imperial China thereafter.

A Crucial Forerunner: The Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE)

Although it lasted only fourteen years, the Qin dynasty integrated much of China and made important administrative and economic innovations. The Qin were but one of many militaristic regimes during the Warring States period (c. 403–221 BCE). What enabled the Qin to prevail over rivals was their expansion into the Sichuan region, which was remarkable for its rich mineral resources and fertile soils. There, a merchant class and the silk trade spurred economic growth, and public works fostered increased food production. These strengths enabled the Qin to defeat the remaining Warring States by 221 BCE and to unify an empire that covered roughly two-thirds of modern-day China.

Supported by able ministers and generals, a large conscripted army, and a system of taxation that financed all-out war, the Qin ruler King Zheng assumed the mandate of heaven from the Zhou. Declaring himself Shi Huangdi, or “First August Emperor,” in 221 BCE, Zheng harkened back to China’s great mythical emperors of antiquity. Forgoing the title of king (wang), which had been used by leaders of the Zhou and Warring States, Zheng instead took the title of di, a word that had meant “ancestral ruler” for the Shang and Zhou, but which had also been used to refer to divine and semidivine figures. He further used the term huang or “august” which had hitherto been used to describe divine forces. By deploying these concepts from traditional religion, Zheng immediately transformed himself in an unprecedented fashion (as Augustus, also a first emperor, was later to do at Rome) into an almost semidivine being.

More information

Map 7.1 is titled, The Qin and Han Dynasties, 221 B C E-220 C E. The map shows the extent of the Qin Empire in 221 B C E, the Han Empire in 206 B C E and then 87 B C E, as well as further territory added to the Han Empire by 210 C E, the area of Xiongnu nomadic tribes, Western regions under Han protectorate, 59 B C E-23 C E, the Great Wall, and the path of Xiongnu invasions. The Qin Empire in 2 2 1 BCE includes a large land area east of the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea. Cities within this area are Pingyang, Chengzhou, Xinzheng, and Luoyang. The Han Empire in 206 B C E added land between the Yellow River and the Yangzi River, including the city of Chang’an, and an area just north of the South China Sea. The Han Empire added land in the Nan Yue from 113 to 111 B C E, Dian in 109 B C E, the peninsula east of the Yellow Sea in 109 to 6 B C E, and an area east of the Taklamakan Desert in 117 to 115 B C E. By 210 C E the Han empire had added further territory west of Dian. Western regions under Han Protectorate from 59 B C E to 23 C E were centered on the Taklamakan Desert. The Great Wall spanned north from the city of Dunhuang, located east of the Taklamakan Desert, all the way east above the Yellow River, toward the peninsula east of the Yellow Sea. Xiongnu’s invasions originated in the Gobi Desert and traveled north, southwest toward the Taklamakan Desert, and South toward the Han Empire.

MAP 7.1 | The Qin and Han Dynasties, 221 BCE–220 CE

The short-lived Qin (221–207 BCE) and the much longer-lasting Han (206 BCE–220 CE) dynasties consolidated much of East Asia into one large regional empire.

- Based on the map, when and where did various phases of expansion take place from the Qin through the Han dynasties? What features shaped that expansion?

- Where was the Great Wall located, and against what was it defending?

- What impact did the pastoral Xiongnu have on the Han dynasty’s effort to consolidate a large territorial state?

Like Augustus (the first Roman emperor) and Napoleon (an emperor in the modern era), Shi Huangdi, the first August Emperor, killed and destroyed on an unprecedented scale, but also established very important instruments of administration and law on which subsequent imperial rule depended. Shi Huangdi centralized the administration of the empire. He forced the defeated rulers of the Warring States and their families to move to Xianyang, the Qin capital—where they would be unable to gather rebel armies. The First August Emperor then parceled out the territory of his massive state into thirty-six provinces, called commanderies (jun). Each commandery had a civilian and a military governor, as well as an imperial inspector. Regional and local officials answered directly to the emperor, who could dismiss them at will. Civilian governors did not serve in their home areas, thus preventing them from building up power for themselves. These reforms provided China with a centralized bureaucracy and a hereditary emperor that later dynasties, including the Han, inherited.

The chief minister of the Qin Empire, Li Si, subscribed to the principles of Legalism developed during the Warring States period. This philosophy valued written law codes, administrative regulations, and inflexible punishments more highly than the rituals and ethics that Confucians emphasized or the spontaneity and natural order that the Daoists stressed. Determined to bring order to a turbulent world, Li Si advocated strict laws and harsh punishments applied to everyone regardless of rank that included beheading, mutilation, and loss of rank and office.

Other methods of control further facilitated Qin rule. Registration of the common people at the age of sixteen provided the basis for taxation and conscription both for military service and public works projects. The Qin emperor established standard weights and measures, as well as a standard currency. The Qin also improved communication systems and administrative efficiency by constructing roads radiating out from their capital to all parts of the empire. Just as crucial was the Qin effort to standardize writing. Banning regional variants of written characters, the Qin required scribes and ministers throughout the empire to adopt the “small seal script,” which later evolved into the less complicated style of bureaucratic writing known as “clerical script” that became prominent during the Han dynasty. In 213 BCE, a Qin decree ordered officials to confiscate and burn all books in private possession, except for technical works on medicine, divination, and agriculture. Education and learning were now under the exclusive control of state officials.

More information

One side of a bronze coin with a hole in the center and a single Chinese symbol on either side.

The agrarian empire of the Qin yielded wealth that the state could tax, and increased tax revenues meant more resources for imposing order. The government issued rules on working the fields, taxed farming households, and conscripted laborers to build irrigation systems and canals so that even more land could come under cultivation. The Qin and, later, the Han dynasties relied on free farmers and conscripted the farmers’ able-bodied sons into their huge armies. Working their own land and paying a portion of their crops in taxes, peasant families were the economic bedrock of the Chinese empire. Long-distance commerce thrived as well. In the dynamic regional market centers of the cities, merchants peddled foodstuffs as well as weapons, metals, horses, dogs, hides, furs, silk, and salt—all produced in different regions and transported on the improved road system. Taxed both in transit and in the market at a higher rate than agricultural goods, these trade goods yielded even more revenue for the imperial government.

More information

The painting has a ruler discussing with a scholar who holds out something in his hands. Just outside the walls, several books are burning while scholars are being attacked and pushed into a large pit.

The Qin dynasty, although short lived, and much criticized by its successors, was fundamental in forging the bases for all subsequent imperial power in China. It reshaped both the agrarian and commercial worlds and encouraged the rapid monetization of the economy. By the careful management of imperial ideals in local contexts it created new identities. And it reshaped rural and remote regions by the use of forced and voluntary settlements. In many ways, the Qin established the parameters within which any subsequent dynasty attempting to rule “All Under Heaven” (tianxia) had to operate.

The Qin grappled with the need to expand and defend their borders, extending those boundaries in the northeast to the Korean Peninsula, in the south to present-day Vietnam, and in the west into central Asia. Relations between the settled Chinese and the nomadic Xiongnu to the north and west (see Chapter 6) teetered in a precarious balance until 215 BCE, when the Qin Empire pushed north into the middle of the Yellow River basin, seizing pasturelands from the Xiongnu and opening the region up for settlement. Qin officials built roads into these areas and employed conscripts and criminals to create a massive defensive wall that covered a distance of 3,000 miles along the northern border (the forerunner of the Great Wall of China—though north of the current wall, which was constructed more than a millennium later). In 211 BCE, the Qin settled 30,000 colonists in the steppe lands of Inner Eurasia.

Despite its military power, the Qin dynasty collapsed quickly, due to constant warfare and the heavy taxation and exhausting conscription that war required. When conscripted workers mutinied in 209 BCE, they found allies in descendants of Warring States nobles, local military leaders, and influential merchants. The rebels swept up thousands of supporters with their call to arms against the “tyrannical” Qin. Shortly before Shi Huangdi died in 210 BCE, even the educated elite joined former lords and regional vassals in revolt. The second Qin emperor committed suicide in 207 BCE, and his weak successor surrendered to the leader of the Han forces later that year. The resurgent Xiongnu confederacy also reconquered their old pasturelands as the dynasty fell. Once again, these more mobile indigenous pastoral nomadic groups on the Eurasian steppes to the north and west commanded spaces distant from imperial power that enabled them to assert considerable independence.

Beginnings of the Western Han Dynasty

The civil war that followed the collapse of Qin rule opened the way for the formation of the Western Han dynasty. A commoner and former policeman named Liu Bang (r. 206–195 BCE) declared himself prince of his home area of Han. In 202 BCE, Liu proclaimed himself the first Han emperor. Claiming the mandate of heaven, the Han portrayed the Qin as evil; yet at the same time they adopted the Qin’s bureaucratic system. In reality, Qin laws had been no crueler than those of the Han. Under Han leadership, China’s armies swelled with some 50,000 crossbowmen who brandished mass-produced weapons made from bronze and iron. Armed with the crossbow, foot soldiers and mounted archers extended Han imperial lands in all directions. Following the Qin practice, the Han also relied on a huge conscripted labor force for special projects such as building canals, roads, and defensive walls.

More information

A reproduction of the wooden bow used by an archer.

A statue of a bronze archer dressed in military armor with a large breastplate. The archer is posed kneeling on one knee.

The first part of the Han dynasty is known as the Western (or Former) Han dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE). The Han brought economic prosperity and the expansion of empire. This was especially the case under Emperor Wu, known also as Han Wudi, who presided over one of the longest and most eventful reigns in Chinese history (r. 141–87 BCE). Though he was called the “Martial Emperor” because of the state’s many military campaigns, Emperor Wu rarely inspected his military units and never led them in battle. Claiming to follow the Daoist principle of wuwei (non-interference), Wu in fact used a stringent penal code to eliminate powerful officials who got in his way, often having them condemned and executed. In a single year, his court system prosecuted over one thousand such cases.

Han Power and Administration

Undergirding the Han Empire was the tight-knit alliance between the imperial family and the new elite—the scholar-gentry class—who shared a determination to impose order on the Chinese population. Although the first Han emperors had no choice but to compromise with the aristocratic groups who had helped overthrow the Qin, in time the Han created the most highly centralized bureaucracy in the world. No fewer than 23,500 individuals staffed the central and local governments. That structure became the source of the Han’s enduring power. As under the Qin, the Han bureaucracy touched everyone because all males had to register, pay taxes, and serve in the military.

The Han court moved quickly to tighten its grip on regional administration. First it removed powerful princes, crushed rebellions, and took over the areas controlled by regional lords. According to arrangements instituted in 106 BCE by Emperor Wu, the empire consisted of thirteen provinces under imperial inspectors. As during the Qin dynasty, commanderies, each administered by a civilian and a military official, covered vast lands inhabited by countless ethnic groups totaling millions of people. These officials maintained political stability and ensured the efficient collection of taxes. However, given the immense numbers under their jurisdiction and the heavy duties they bore, in many respects the local administrative staff was still inadequate to the tasks facing it.

Government schools that promoted the scholar ideal became fertile sources for recruiting local officials. In 136 BCE, Emperor Wu founded what became the Imperial University, a college for classical scholars that supplied the Han need for well-trained bureaucrats. By the second century CE, the university boasted 30,000 students and faculty. Apart from studying the classics, Han scholars were naturalists and inventors. They made important medical discoveries, dealing with rational explanations of the body’s functions and the role of wind and temperature in transmitting diseases. They also developed the magnetic compass and high-quality paper. Local elites encouraged their sons to master the classical teachings. This practice could secure future entry into the ruling class and firmly planted the Confucian classics at the heart of the imperial state.

Confucian thought slowly became the ideological buttress of the Han Empire. Under Emperor Wu, the bureaucracy deemed people’s welfare to be the essential purpose of legitimate rule. By 50 BCE, The Analects, a collection of Confucius’s sayings, was widely disseminated, and three Confucian ideals reigned as the official doctrine of the Han Empire: honoring tradition, respecting the lessons of history, and acknowledging the emperor’s responsibility to heaven. Scholars used Confucius’s words to tutor the princes. By embracing Confucian political ideals, Han rulers established an empire based on the mandate of heaven and crafted a careful balance in which the officials provided a counterweight to the emperor’s autocratic strength. When the interests of the court and the bureaucracy clashed, however, the emperor’s will was paramount.

The Han Economy and the New Social Order

Part of the Han leaders’ genius was their ability to win the support of diverse social groups that had been fighting over local resources for centuries. The basis of their success was their ability to organize daily life, create a stable social order, promote economic growth, and foster a state-centered religion. One important element in promoting political and social stability was that the Han allowed surviving Qin aristocrats to reacquire some of their former power. The Han also urged enterprising peasants who had worked the nobles’ lands to become local leaders in the countryside. Successful merchants won permission to extend their influence in cities, and in local areas scholars found themselves in the role of masters when the state removed their lords.

Out of a massive agrarian base flowed a steady stream of tax revenues and labor for military forces and public works. The Han court drew revenues from many sources: state-owned imperial lands, mining, and mints; tribute from outlying domains; household taxes on the nobility; and taxes on surplus grains from wealthy merchants. Emperor Wu established state monopolies in salt, iron, and wine to fund his expensive military campaigns. His policies encouraged silk and iron production—especially iron weapons and everyday tools—and controlled profiteering through price controls. He also minted standardized copper coins and imposed stiff penalties for counterfeiting.

More information

A terra-cotta model of a three-story Han watchtower. The model has soldiers with crossbows on the upper balcony, while another figure sits in front of the main entrance on the bottom level.

Han cities were laid out in an orderly grid. Bustling markets served as public areas. Carriages transported rich families up and down wide avenues (and they paid a lot for the privilege: keeping a horse required as much grain as a family of six would consume). Court palaces became forbidden inner cities, off-limits to all but those in the imperial lineage or the government. Monumental architecture in China announced the palaces and tombs of rulers.

DOMESTIC LIFE Daily life in Han China included new luxuries for the elite and reinforced traditional ideas about gender. Wealthy families lived in several-story homes with richly carved crossbeams and rafters and floors cushioned with embroidered pillows, wool rugs, and mats. Fine embroideries hung as drapes, and screens in the rooms secured privacy. Domestic space reinforced male authority as women and children stayed cloistered in inner quarters, preserving the sense that the patriarch’s role was to protect them from a harsh society.

Nonetheless, some elite women, often literate, enjoyed respect as teachers and managers within the family while their husbands served as officials away from home. Ban Zhao, the younger sister of the historian Ban Gu (32–92 CE), was an exceptional woman whose talents reached outside the home. She became the first female Chinese historian and lived relatively unconstrained. After marrying a local resident, Cao Shishu, at the age of fourteen, she was called Madame Cao at court. Subsequently, she completed her elder brother’s History of the Former Han Dynasty when he was imprisoned and executed. In addition to completing the first full dynastic history in China, Ban Zhao wrote Lessons for Women, in which she described the status of elite women and presented the ideal woman in light of her virtue, her type of work, and the words she spoke and wrote. The importance of women within the family was reflected in the women at court who as heiress “empresses” (first order of succession) wielded powers behind the throne, including the empresses Lü and Dou at the turn of the second century BCE. Women who were commoners led much less protected lives. Many did hard labor in the fields, and some joined troupes of entertainers to sing and dance for food at open markets.

Silk was abundant and available to all classes, though in winter only the rich wrapped themselves in furs while everyone else stayed warm in woolens and ferret skins. The rich also wore distinctive slippers lined with leather or silk. Wine and cooked meat came to the dinner tables of the wealthy on vessels fashioned with silver inlay or golden handles. Entertainment for those who could afford it included gambling, performing animals, tiger fights, foreign dancing girls, and even live music in private homes, performed by orchestras in the families’ private employ. Although events like these had occurred during the Zhou dynasty, they had marked only public ritual occasions.

More information

A statue of a dancing girl wearing robes with long sleeves. Parts of the statue have been broken off, including one of the arms and part of the back of the head.

A statue of a smiling entertainer holding a drum and a stick. The figure is posed sitting while holding the drum under one arm, holding the stick in the other, and with one foot held out in front of it.

A clay diagram shows figures performing acrobatics while people stand to the side watching. A figure stands nearby while two of the acrobats face each other while standing on their hands, holding their legs above their heads. One of the acrobats is lifting another acrobat into the air. Two acrobats contort their bodies, one crouching with their head between their legs and the other contorting their arms behind their back. The onlookers along the sides sit with their arms held out in front of them, hands together but obscured by their sleeves.

SOCIAL HIERARCHY At the base of Han society was a free peasantry of farmers who owned and tilled their own land. The Han court upheld an agrarian ideal—which Confucians and Daoists supported—honoring the peasants’ productive labors, while subjecting merchants to a range of controls (including regulations on luxury consumption) and belittling them for not doing physical labor. Confucians envisioned scholar-officials as working hard for the ruler to enhance a moral economy in which profiteering by greedy merchants would be minimal.

In reality, however, the first century of Han rule perpetuated the power of elites. At the apex were the imperial clan and nobles, followed, in order, by high-ranking officials and scholars, great merchants and manufacturers, and a regionally based class of local magnates. Below these elites, lesser clerks, medium and small landowners, free farmers, artisans, small merchants, poor tenant farmers, and hired laborers eked out a living. The more destitute became enslaved government workers and relied on the state for food and clothing. At the bottom were convicts and people who were privately enslaved.

Between 100 BCE and 200 CE, scholar-officials linked the imperial center with local society. At first, their political clout and prestige complemented the power of landlords and large clans, but over time their autonomy grew as they gained wealth by acquiring private property. Following the fall of the Han, they emerged as the dominant aristocratic clans.

In the long run, the imperial court’s struggle to limit the power of local lords and magnates failed. Rulers had to rely on local officials to enforce their rule, but those officials could rarely stand up to the powerful men they were supposed to be governing. And when central rule proved too onerous for local elites, they could rebel. Local uprisings against the Han that began in 99 BCE forced the court to relax its measures and left landlords and local magnates as dominant powers in the provinces. Below these privileged groups, powerless agrarian groups turned to Daoist religious organizations that crystallized into potent cells of dissent.

RELIGION AND OMENS Under Emperor Wu, Confucianism took on religious overtones. One treatise portrayed Confucius not as a humble teacher but as an uncrowned monarch, and even as a demigod and a giver of laws, which differed from the portrait in The Analects of a more modest, accessible, and very human Confucius.

Although Confucians at court championed classical learning, many local communities practiced forms of a remarkably dynamic popular Chinese religion. Imperial cults, magic, and sorcery reinforced the court’s interest in astronomical omens—such as the appearance of a supernova, solar halos, meteors, and lunar and solar eclipses. Unpredictable celestial events, as well as earthquakes and famines, could be taken to mean that the emperor had lost the mandate of heaven. Powerful ministers exploited these occurrences to intimidate their ruler. People of high and low social position alike believed that witchcraft could manipulate natural events and interfere with the will of heaven. Religion in its many forms, from philosophy to witchcraft, was an essential feature of Han society from the elite to the poorer classes.

Military Expansion and the Silk Roads

The Han military machine was effective at expanding the empire’s borders and enforcing stability around the borderlands. Peace was good for business, specifically for creating stable conditions that allowed the safe transit of goods over the Silk Roads. Emperor Wu did much to transform the military forces. Following the Qin precedent, he made military service compulsory, resulting in a huge force: 100,000 crack troops in the Imperial Guard stationed in the capital and more than 1 million in the standing army.

EXPANDING BORDERS Han forces were particularly active along the borders. During the reign of Emperor Wu, Han control extended from southeastern China to northern Vietnam. When pro-Han Koreans appealed for Han help against rulers in their fight over local resources, Emperor Wu’s expeditionary force defeated the Korean king, and four Han commanderies sprang up in northern Korea. Han incursions into Sichuan and the southwestern border areas were less successful due to mountainous terrain and malaria. Here the terrain, including rugged highlands and watery, marshy lowlands, favored the independence of the local non-Han peoples. Just as the Han saw the deadly diseases, poisonous plants, and predatory animals as dangerous, they regarded the indigenous peoples (sometimes threateningly tattooed) as “savage tribesmen” whom the Han would need the full power of the state to control.

Especially in mountainous highland areas of Dian in the southwest, a mosaic of non-Han peoples, often distant from state control, remained recalcitrant to the penetration of the imperial state and its culture. Even when peoples like the Mimo and Dian adopted Han models, like writing, they often did so to assert their own traditions. Nevertheless, a commandery took root in southern Sichuan in 135 BCE, and soon it opened trading routes to Southeast Asia.

The Han Empire’s most serious military threat, however, continued to come from the Xiongnu and other nomadic peoples in the north. The Han inherited from the Qin a symbiotic relationship with these proud, horse-riding nomads: Han merchants brought silk cloth and thread, bronze mirrors, and lacquerware to exchange for furs, horses, and cattle. After humiliating defeats at the hands of the Xiongnu, the Han under Emperor Wu successfully repelled Xiongnu invasions around 120 BCE and ultimately penetrated deep into Xiongnu territory. The Xiongnu tribes were split in two, with the southern tribes surrendering and the northern tribes gradually moving west, ultimately threatening Roman territory.

THE CHINESE PEACE AND THE SILK ROADS The retreat of the Xiongnu and other nomadic peoples introduced a glorious period of internal peace and prosperity some scholars have referred to as a Pax Sinica (“Chinese Peace,” 149–87 BCE). During this period, long-distance trade flourished, cities ballooned, standards of living rose, and the population surged. As a result of their military campaigns, Emperor Wu and his successors enjoyed tribute from distant subordinate states, intervening in their domestic policy only if they rebelled. The Han instead relied on trade and markets to incorporate outlying lands as prosperous satellite states within the tribute system. The Xiongnu nomads even became key middlemen in Silk Road trade.

When the Xiongnu were no longer a threat from the north, the Han expanded westward. (See Map 7.2.) By 100 BCE, Emperor Wu had extended the northern defensive wall from the Tian Shan Mountains to the Gobi Desert. Along the wall stood signal beacons for sending emergency messages, and its gates opened periodically for trading fairs. The westernmost gate was called the Jade Gate, since jade from the Taklamakan Desert passed through it. Wu also built garrison cities at oases to protect the trade routes. Soldiers at these oasis garrison cities settled with their families on the frontiers. When its military power expanded beyond the Jade Gate, the Han government set up a similar system of oases on the rim of the Taklamakan Desert. With irrigation, oasis agriculture attracted many more settlers. Trade routes passing through deserts and oases now were safer and more reliable—until fierce Tibetan tribes threatened them at the beginning of the Common Era—than the steppe routes, which they gradually replaced.

THE HAN EMPIRE AND DEFORESTATION The Han dynasty had a significant, if unintended, impact on the environment. As the Han peoples moved southward and later westward, filling up empty spaces, colonizing the indigenous peoples whom they encountered, and driving elephants, rhinoceroses, and other animals into extinction, the farming communities cleared immense tracts of land of shrubs and forests to prepare for farming. The Han were especially fond of oak, pine, ash, and elm, and their artists celebrated them in paintings; farmers, however, saw forests as a challenge to their work. China’s grand environmental narrative has been the clearing of old-growth forests that had originally covered the greater part of the territory of China.

But trees prevent erosion, and one of the results of the massive deforestation campaigns during the Han period in the regions surrounding the Yellow River was massive runoffs of soil into the river. In fact, the Yellow River owes its name to the immense quantities of mud that it absorbed from surrounding farmlands. This sediment raised the level of the river above the surrounding plain in many places. In spite of villagers’ efforts to build levees along the river’s banks, severe flooding occurred, threatening crops, destroying villages, and even undermining the legitimacy of ruling dynasties. During most of the Han period, a break in the levees took place every sixteen years. The highest concentration of flooding was between 66 BCE and 34 CE, when severe floods occurred every nine years. As in many empires, the Han’s expansion was based on expanded agriculture and brisk trade, but expansion came at a major environmental price: deforestation, flooding, and the destruction of the habitats of many plants and animals.

More information

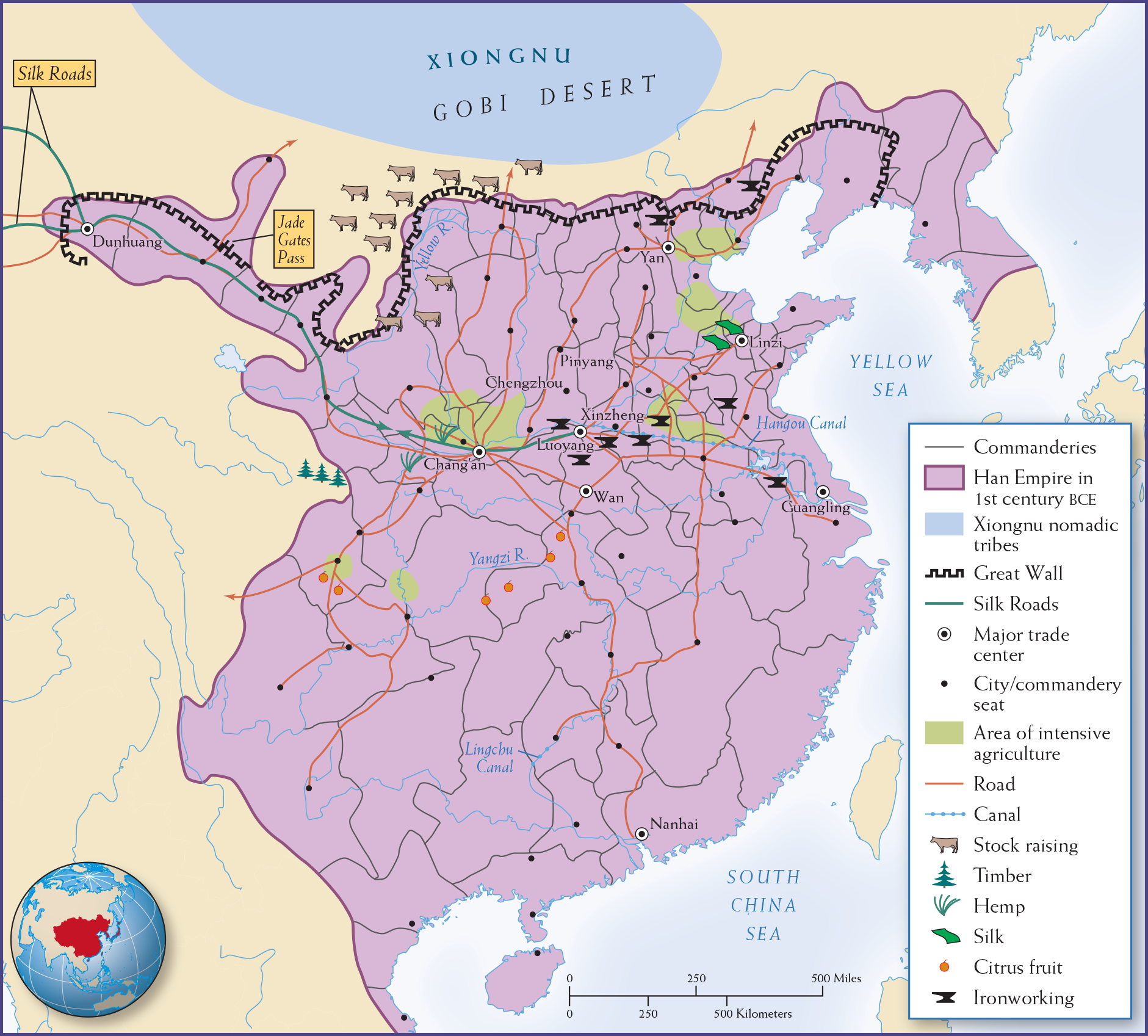

Map 7.2 is titled, Pax Sinica: The Han Empire in the First Century B C E. Shaded regions on the map illustrate the boundaries of the Han Empire, which run south of the Yellow River and the Great wall all the way down to the South China Sea. The map also highlights areas of intensive agriculture near Chang’an, Xinzheng, and Yan. Major trade centers include Dunhuang, Yan, Linzi, Chang’an, Luoyang, Wan, Guanghing, and Nanhai. Major cities are mostly located along roads that span the Han Empire. The Great Wall aligns with the northern boundary for large sections, and around these areas, the stock is raised. There is a large region where ironwork is done near Xinzheng. Silk is produced near Linzi. Hemp is produced near Chang’an. Citrus fruit is produced near the center of the Han Empire. The Han Empire also has a vast network of roads and canals, along which the Silk Road runs from Dunhuang to Luoyang. Xiongnu nomadic tribes live north of the Great Wall in the Gobi desert.

MAP 7.2 | Pax Sinica: The Han Dynasty in the First Century BCE

Agriculture, commerce, and industry flourished in East Asia under Han rule.

- According to the map, what were the main commodities in the Han dynasty, where were they located, and along what routes might they have moved to pass among the empire’s regions?

- Locate the lines marking the commanderies into which Han territory was divided. What do you notice about their comparative size, resources, and other features?

- What do you notice about the location of major trade centers and the areas of intensive agriculture?

The Later (Eastern) Han Dynasty

After Wang Mang’s fall, social, political, and economic inequalities fatally weakened the power of the emperor and the court. As a result, the Later (or Eastern) Han dynasty (25–220 CE), with its capital at Luoyang on the North China plain, followed a hands-off economic policy under which large landowners and merchants amassed more wealth and more property. Decentralizing the regime was also good for local business and long-distance trade, as the Silk Roads continued to flourish. Chinese silk became popular as far away as the Roman Empire. In return, China received from points west on the Silk Roads commodities including glass, jade, horses, precious stones, tortoiseshells, and fabrics. (See Current Trends in World History: Han China, the Early Roman Empire, and the Silk Roads.)

By the second century CE, landed elites enjoyed the fruits of their success in manipulating the Later (Eastern) Han tax system. It granted them so many land and labor exemptions that the government never again firmly controlled its human and agricultural resources as Emperor Wu had. As the court refocused on the new capital in Luoyang, local power fell into the hands of great aristocratic families. These elites acquired even more privately owned land and forced free peasants to become their rent-paying tenants, then raised their rents higher and higher.

Current Trends in World History

Han China, the Early Roman Empire, and the Silk Roads

This chapter offers detailed information allowing for a comparison of the globalizing empires of imperial Rome and Han China. To what extent, however, were these powerful, contemporary forces in contact with each other? Because the Roman Empire and Han China were separated by 5,000 miles, harsh terrain, and the powerful Parthian Empire, scholars have wondered about their interaction and knowledge of each other. (See Map 7.5.) In the nineteenth century, European archaeologists created the term “Silk Road,” stressing the commercial linkages between these two great empires. (See Chapter 6 for more on the early Silk Roads.) Many twentieth-century historians have challenged this view: first, questioning the validity of the term due to its emphasis on silk exchange to the exclusion of other traded commodities, and, second, questioning the extent of direct, or even indirect, commercial exchanges between Han China and the Roman Empire. Some modern historians see the very idea of a Silk Road as part of a de-Europeanizing trend among global historians who are committed to elevating the Chinese as the true entrepreneurs of the age.

More information

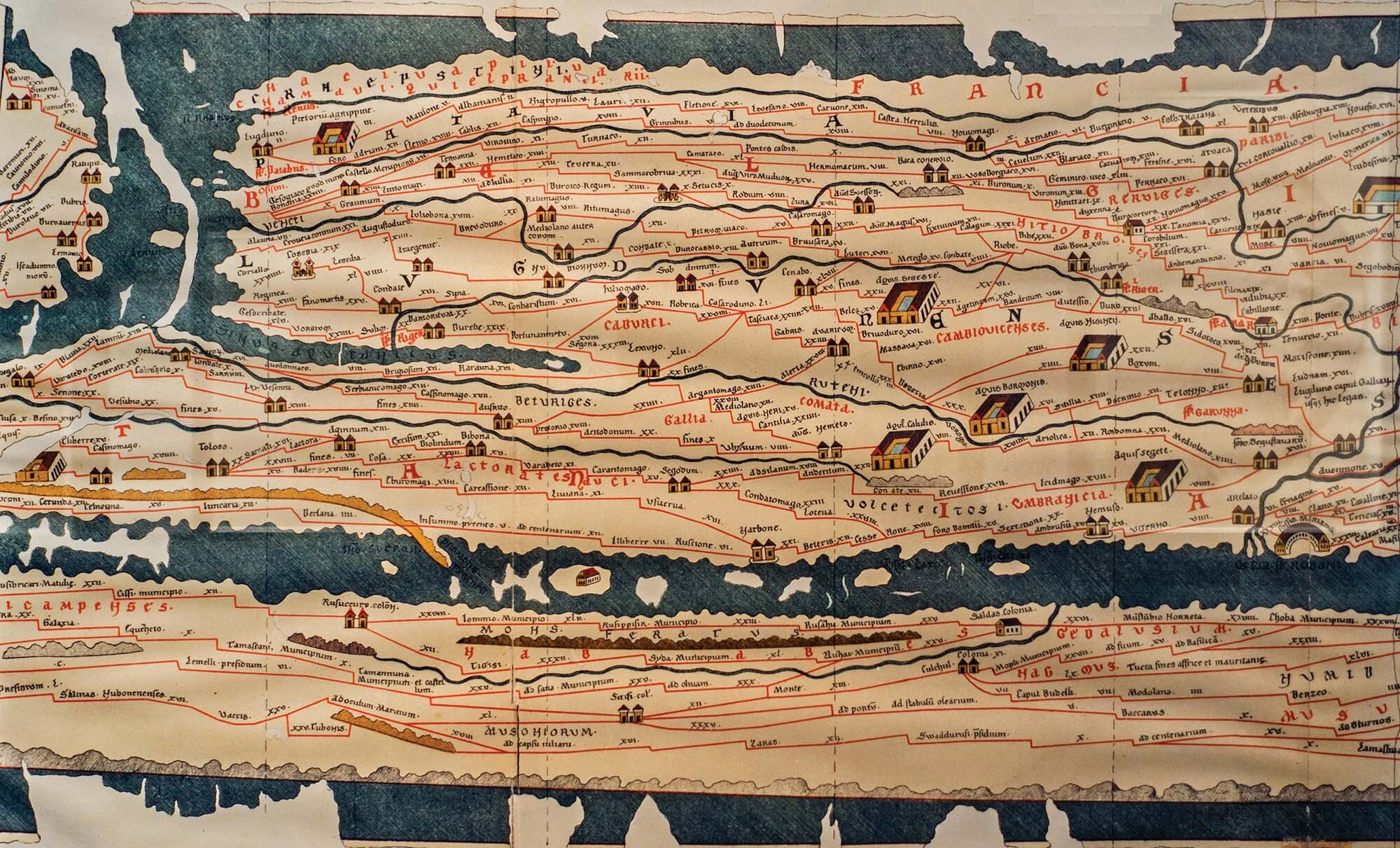

The Peutinger table shows topographical features such as rivers and mountain ranges, roads, towns, and ports. It shows France, part of the Mediterranean Sea, and North Africa.

Already by the reign of Augustus, substantial amounts of Chinese silk were available in the Mediterranean world. David F. Graf observes that the late first-century BCE poets Virgil and Ovid have many references to Chinese silk. Another first-century BCE poet, Horace, was more explicit about the use of Chinese silks, writing that “the sheer and transparent qualities of serica [silk] dresses became a symbol of degeneracy of the emperors and aristocratic women, drawing condemnation.” In the late first century CE, natural historian Pliny the Elder commented somewhat disdainfully on trade with the Seres (the “Silk People”): “Though mild in character, the Chinese still resemble wild animals in that they shun the company of the rest of humankind and wait for trade to come to them.” While the Peutinger Table, a map (or itinerary) thought to reveal early first-century CE geographic knowledge, does not reach as far as China in the east, the Romans had sufficient information by the middle of the second century CE to enable mapmakers drawing on Ptolemy’s Geography to locate China and the rest of East Asia on their map of the world.

The Han emperor most responsible for beginning to expand Chinese influence westward, opening up trade routes to China’s west and gaining knowledge of western regions, was Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BCE). In 139 BCE, Wu sent an official, Zhang Qian, accompanied by more than 100 men, on a mission to the west. The primary goal of this mission was to secure alliances with central Asian states, most importantly the Yuezhi, against the Xiongnu nomads, who threatened the Han at this time. On his way to the Yuezhi, Zhang Qian was detained by a Xiongnu chieftain for ten years, during which he married a Xiongnu woman and had children with her. While in captivity, Zhang Qian gathered information on the commodities from this region and beyond, including Bactria, India, and Persia. He shared this information when he eventually escaped and returned to the Han capital at Chang’an. In short, Wu’s diplomatic and military moves expanded Han China’s understanding of the west and knowledge of routes through which silk could be shipped westward.

A second major Chinese initiative regarding the west occurred around the end of the first century CE and the beginning of the second. Here, the leading figure was General Ban Ch’ao (brother of Ban Zhao, who wrote the Lessons for Women excerpted at the end of this chapter). Ban Ch’ao held the office of Protector of the Western Territories between 91 and 101 CE. He brought the whole of the Tarim Basin under Chinese rule and established a set of forts on routes leading westward. He dispatched one of his adjuncts, Gan Ying, to travel westward and gather information on regions thus far unexplored by the Chinese. Gan Ying did not reach Rome, though his mission was to do so. Nevertheless, journeying only as far as the Black Sea or the Persian Gulf, he did acquire much information about Rome and its dependent states.

The Roman Empire was known to the Chinese as Da Qin (the “Great Qin”). Gan Ying viewed Da Qin accurately in some respects and fantastically in others. The Chinese sources portrayed the Romans through their own spectacles, seeing Rome as “an idealized China, a Taoist utopia, a fictitious religious world divorced from reality.” According to Chinese sources, the first direct contact with the Roman Empire occurred during the ninth year of the reign of Huandi (166 CE), when a private Roman merchant arrived at the Chinese commandery on the central Vietnamese coast with “gifts of elephant tusks, rhinoceros horn, and tortoise shell” during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. The Chinese court was unimpressed by these offerings, even wondering if the reports of Rome’s power had been exaggerated.

Most of the Chinese silk that reached the Mediterranean regions came by sea via the route described in the Periplus Maris Erythraei (see Chapter 6), often through the Persian Gulf and Red Sea and then overland to ports along the coast of present-day Syria. But the overland route, which most scholars have called the Silk Road, was also in use at this time. The entry point for much Chinese silk was Palmyra. Trade through Palmyra reached its high point in the second century CE. To date, the largest quantity of silk found outside China and dated to ancient times has been discovered in Palmyra. The polychrome silk weaving found in Palmyra can be traced back to imperial Chinese workshops. The conclusion of the most recent scholarship on the Silk Roads and Chinese-Roman relations is that “there was significant movement of peoples and goods along segments of the ‘Silk Route’ during the Roman imperial era,” but the relations between the Chinese and the Romans were still remote and “indirect.”

Sources: David F. Graf, “The Silk Road between Syria and China,” in Trade, Commerce, and the State in the Roman World, edited by Andrew Wilson and Alan Bowman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 443–529 (quotations are from pp. 444, 460, 477–78).

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- What is the evidence for exchange between the Romans and the Han Chinese? What were the impediments to direct interaction between Rome and Han China?

- What did the Romans think about trade with Han China? What did the Chinese think of Rome?

- How does the evidence for interconnectivity between Rome and Han China influence your understanding of the comparative picture of these two globalizing empires?

EXPLORE FURTHER

Hansen, Valerie, The Silk Road: A New History (2012).

Liu, Xinru, The World of the Ancient Silk Road (2012).

Such prosperity bred greater social inequity—among large landholders, tenant farmers, and peasants working their small parcels—and a renewed source of turmoil. Simmering tensions between landholders and peasants boiled over in a full-scale rebellion in 184 CE. Popular religious groups championed new ideas among commoners and elites for whom the many-centuries-earlier Daoist sage Master Laozi, the voice of naturalness and spontaneity, was an exemplary model. Daoist masters challenged Confucian ritual conformity, and they advanced their ideas in the name of a divine order that would redeem all people, not just elites. Officials, along with other political outcasts, headed strong dissident groups and eventually formed local movements. Under their leadership, religious groups such as the Yellow Turbans—so called because they wrapped yellow scarves around their heads—championed Daoist upheaval across the empire. The Yellow Turbans drew on Daoist ideas to call for a just and ideal society. Their message received a warm welcome from a population that was increasingly hostile to Han rule.

Proclaiming the Daoist millenarian belief in a future “Great Peace,” the Yellow Turbans demanded fairer treatment by the Han state and equal distribution of all farm lands. As agrarian conditions worsened, a widespread famine ensued. It was a catastrophe that, in the rebels’ view, demonstrated the emperor’s loss of the mandate of heaven. While Han military forces were successful in quashing the rebellion, significant damage had been done to Han rule. The economy disintegrated when people refused to pay taxes and provide forced labor, and internal wars engulfed the dynasty. After the 180s CE, three competing states replaced the Han: the Wei in the northwest, the Shu in the southwest, and the Wu in the south. A long-lasting unified empire did not return for several centuries.

Glossary

- Shi Huangdi

- Title taken by King Zheng in 221 BCE, when he claimed the mandate of heaven and consolidated the Qin dynasty. He is known for his tight centralization of power, including standardizing weights, measures, and writing; constructing roads, canals, and the beginnings of the Great Wall; and preparing a massive tomb for himself filled with an army of terra-cotta warriors.

- commanderies

- The thirty-six provinces (jun) into which Shi Huangdi divided territories. Each commandery had a civil governor, a military governor, and an imperial inspector.

- Emperor Wu

- (r. 141–87 BCE) Also known as Emperor Han Wudi, or the “Martial Emperor”; the ruler of the Han dynasty for more than fifty years, during which he expanded the empire through his extensive military campaigns.

- Imperial University

- Institution founded in 136 BCE by Emperor Wu (Han Wudi) not only to train future bureaucrats in the Confucian classics but also to foster scientific advances in other fields.

- Pax Sinica

- Modern term (paralleling the term Pax Romana) for the “Chinese Peace” that lasted from 149 to 87 BCE, a period when agriculture and commerce flourished, fueling the expansion of cities and the growth of the population of Han China.

Social Upheaval and Natural Disaster

The strain of military expenses and the tax pressures those expenditures placed on small landholders and peasants were more than the Han Empire could bear. By the end of the first century BCE, heavy financial expenditures had drained the Chinese empire. A devastating chain of events exacerbated the empire’s troubles: natural disasters led to crop failures, which led to landowners’ inability to pay taxes that were based not on crop yield but on landholding size. Wang Mang (r. 9–23 CE), a former Han minister and regent to a child emperor, took advantage of the crisis. Believing that the Han had lost the mandate of heaven, Wang Mang assumed the throne in 9 CE and established a new dynasty. He designed reforms to help the poor and to foster economic activity. He made efforts to stabilize the economy by confiscating gold from wealthy landowners and merchants, introducing a new currency, and attempting to minimize price fluctuations. By redistributing excess land, he hoped to allow all families to work their own parcels and share in cultivating a communal plot whose crops would become tax surplus for the state.

Wang Mang’s regime, and his idealistic reforms, failed miserably. Violent resistance from peasants and large landholders, as well as the Yellow River’s change in its course in 11 CE, contributed to his demise. When the Yellow River, appropriately called “China’s Sorrow,” changed course—as it has many times in China’s long history—tremendous floods caused mass death, vast migrations, peasant impoverishment, and revolt. The floods of 11 CE likely affected half the Chinese population. Rebellious peasants, led by Daoist clerics, used this far-reaching disaster as a pretext to march on Wang’s capital at Chang’an. The peasants painted their foreheads red in imitation of demon warriors and called themselves Red Eyebrows. By 23 CE, they had overthrown Wang Mang. The natural disaster was attributed by Wang’s rivals to his unbridled misuse of power, and soon Wang became the model of the evil usurper.