A Connected World

CORE OBJECTIVES

COMPARE the internal integration and external interactions of sub-Saharan Africa with those of the Americas, and with the connected Eurasian world.

Worlds Coming Together: Sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas

From 1000 to 1300 CE, sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas became far more internally integrated—culturally, economically, and politically—than before. Islam’s spread and the growing trade in gold, enslaved people, and other commodities brought sub-Saharan Africa more fully into the exchange networks of the Eastern Hemisphere, but the Americas remained isolated from Afro-Eurasian networks for several more centuries.

Sub-Saharan Africa Comes Together

During this period, sub-Saharan Africa’s interactions with the rest of the world dramatically changed. While sub-Saharan Africa before 1000 CE had never been a world entirely apart, its integration with Eurasia now strengthened. Interior hinterlands increasingly found themselves touched by the commercial and migratory impulses emanating from transformations in the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea. (See Map 10.8.)

WEST AFRICA AND THE MANDE-SPEAKING PEOPLES Once trade routes bridged the Sahara Desert (see Chapter 9), the flow of commodities and ideas linked sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa and Southwest Asia. As the savanna region increasingly connected to developments in Eurasia, Mande-speaking peoples became the primary agents for integration within and beyond West Africa. Exploiting their expertise in commerce and political organization, the Mande edged out rivals. The Mande homeland was a vast area, 1,000 miles wide, between the bend in the Senegal River to the west and the bend of the Niger River to the east, and stretching more than 2,000 miles from the Senegal River in the north to the Bandama River in the south.

By the eleventh century, the Mande-speaking peoples were spreading their cultural, commercial, and political hegemony from the savanna grasslands southward into the woodlands and tropical rain forests that stretched to the Atlantic Ocean. Those dwelling in the rain forests organized small-scale societies led by local councils, while those in the savanna developed centralized forms of government under sacred kingships. Mande speakers believed that their kings had descended from the gods and that they enjoyed the gods’ blessing.

As the Mande extended their territory to the Atlantic coast, they gained access to tradable items that residents of Africa’s interior were eager to have—notably peppers and kola nuts, for which the Mande exchanged iron products and manufactured textiles. Mande-speaking peoples, with their far-flung commercial networks and highly dispersed populations, dominated the trans-Saharan trade in salt from the northern Sahel, gold from the Mande homeland, and enslaved people from across the region. By 1300, Mande-speaking merchants had followed the Senegal River to its outlet on the Atlantic coast and then pushed their commercial frontiers farther inland and down the coast. Thus, even before European explorers and traders arrived in the mid-fifteenth century, West African peoples had created dynamic networks linking the hinterlands with coastal trading hubs.

THE MALI EMPIRE In the early thirteenth century, the Mali Empire became the Mande successor state to the kingdom of Ghana (see Chapter 9). The origins of the Mali Empire and its legendary founder are enshrined in The Epic of Sundiata. Sundiata’s triumph, which occurred in the first half of the thirteenth century, marked the victory of new cavalry forces over traditional foot soldiers. Horses now became prestige objects for the savanna peoples, symbols of state power.

Mansa Musa’s Hajj

More information

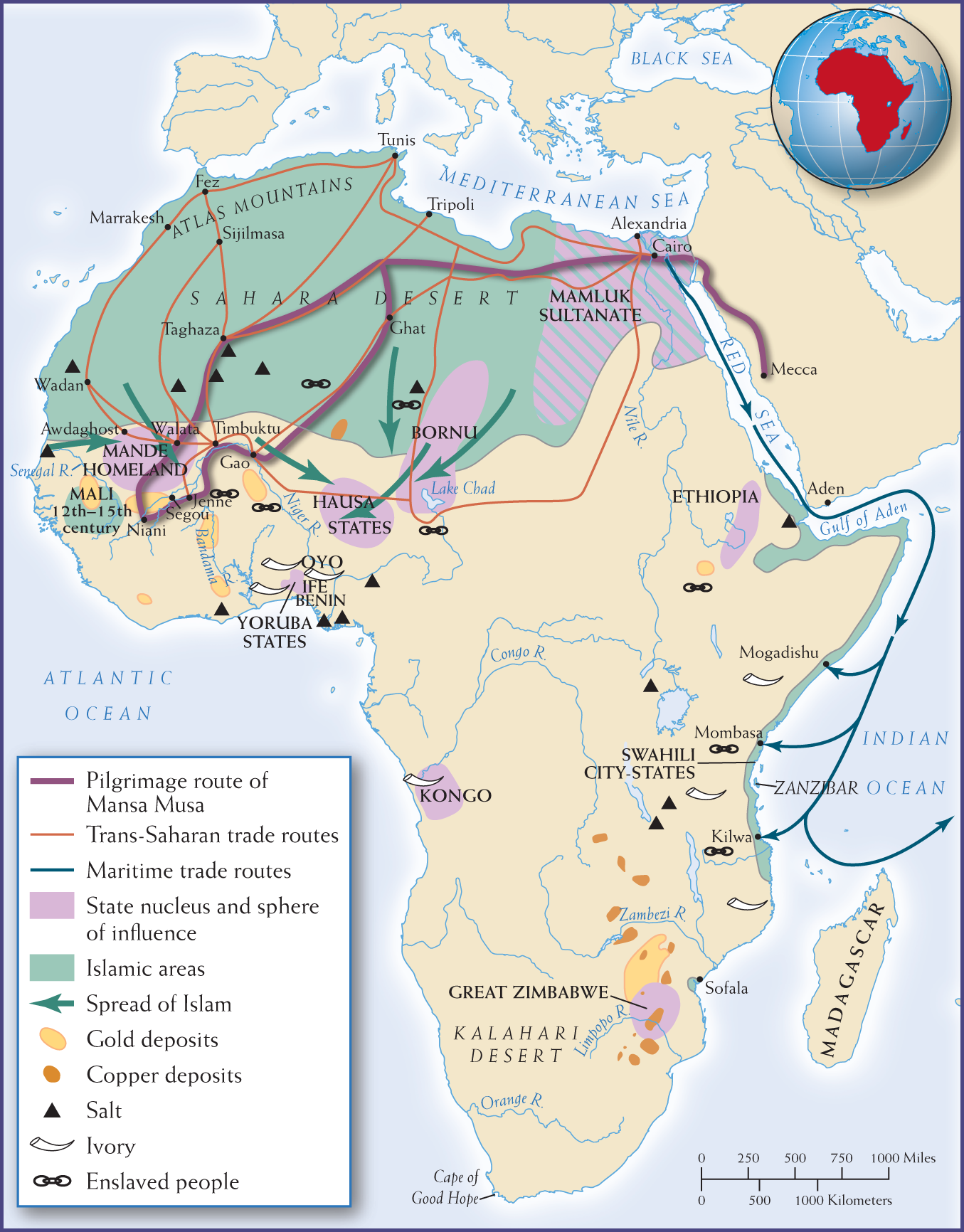

Map 10.8 is titled Sub-Saharan Africa, 1300. The map shows the pilgrimage route of Mansa Musa across the Sahara, Trans-Saharan and maritime trade routes, various state nuclei and spheres of influence, Islamic areas, the spread of Islam, gold and copper deposits, and the location of salt, ivory, and slaves. The Sahara Desert (criss-crossed by trade routes) and most of the northern part of Africa are under Islamic influence, as are a sliver of land along the coast of the Horn of Africa. The Mamluk Sultanate has its state nucleus and sphere of influence that covers present-day Egypt. The other state nuclei and their spheres of influence are Mande Homeland, Bornu, Hausa States, Yoruba States, Kongo, Great Zimbabwe, and Ethiopia. Maritime trade routes run south through the Red Sea and then around the Horn of Africa. Gold deposits, copper deposits, salt, ivory, and slave commodities are scattered across the continent.

MAP 10.8 | Sub-Saharan Africa, 1300

Increased commercial contacts influenced the religious and political dimensions of sub-Saharan Africa at this time. Compare this map with Map 9.3.

- Where had strong Islamic communities emerged by 1300? By what routes might Islam have spread to those areas?

- According to this map, what types of activity were taking place in sub-Saharan West Africa?

- What goods were traded in sub-Saharan Africa, and along what routes did those exchanges take place?

Under the Mali Empire, commerce took off. With Mande trade routes extending to the Atlantic Ocean and spanning the Sahara Desert, West Africa was no longer an isolated periphery of the central Muslim lands. Mansa Musa (r. 1312–1332), perhaps Mali’s most famous sovereign, made a celebrated hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca, in 1324–1325. He traveled through Cairo and impressed crowds with the size of his retinue—including soldiers, wives, consorts, and as many as 12,000 enslaved people—and his displays of wealth, especially many dazzling items made of gold. Mansa Musa’s lengthy three-month stopover in Cairo, one of Islam’s primary cities, astonished the Egyptian elite and awakened much of the world to the fact that Islam had spread far below the Sahara and that a sub-Saharan state could mount such an impressive display of wealth and power.

More information

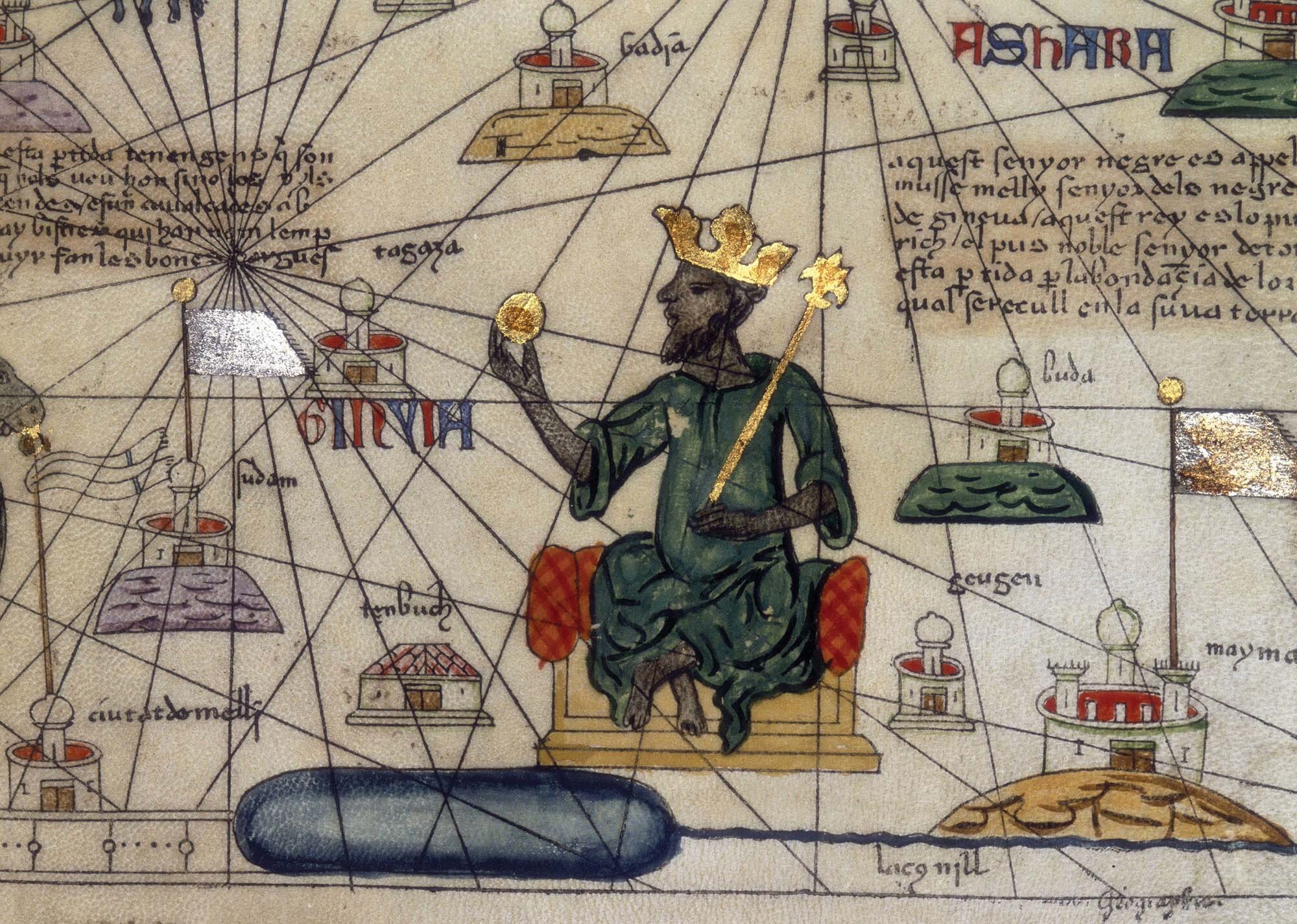

A painting of the King of Mali. The king sits on a throne, wears a crown, and holds up a golden staff and a golden ball. The painting of the king is placed on top of a map of Mali with small illustrations of buildings denoting different locations. There is script scattered throughout the painting and in a large block at the top right corner.

The Mali Empire boasted two of West Africa’s largest cities. Jenne, an entrepôt dating back to 200 BCE, was a vital assembly point for caravans laden with salt, gold, and enslaved people preparing for journeys west to the Atlantic coast and north across the Sahara. More spectacular was the city of Timbuktu; founded around 1100 as a seasonal camp for nomads, it grew in size and importance under the patronage of various Mali kings. By the fourteenth century, it was a thriving commercial, intellectual, and religious center famed for its three large mosques, which are still standing.

TRADE BETWEEN EAST AFRICA AND THE INDIAN OCEAN Africa’s eastern and southern regions were also integrated into long-distance trading systems. Because of the monsoon winds, East Africa was a logical end point for much of the Indian Ocean trade. Swahili peoples living along that coast became brokers for trade from the Arabian Peninsula, the Persian Gulf territories, and the western coast of India. Merchants in the city of Kilwa on the coast of present-day Tanzania brought ivory, gold, enslaved people, and other items from the continent’s interior and shipped them to destinations around the Indian Ocean.

Shona-speaking peoples grew rich by mining the gold ore in the highlands between the Limpopo and Zambezi Rivers. By 1000 CE, the Shona had founded up to fifty small religious and political centers, each one erected from stone to display its power over the peasant villages surrounding it. Around 1100, one of these centers, Great Zimbabwe, stood supreme among the Shona. Built on the fortunes made from gold, its most impressive landmark was a massive elliptical building made of stones fitted so expertly that they needed no grouting.

More information

A wide view of the ruins and the Great Enclosure of Great Zimbabwe. The ruins are comprised of stone walls and piles of various heights. There is grass in the foreground and a hill with trees in the background.

More information

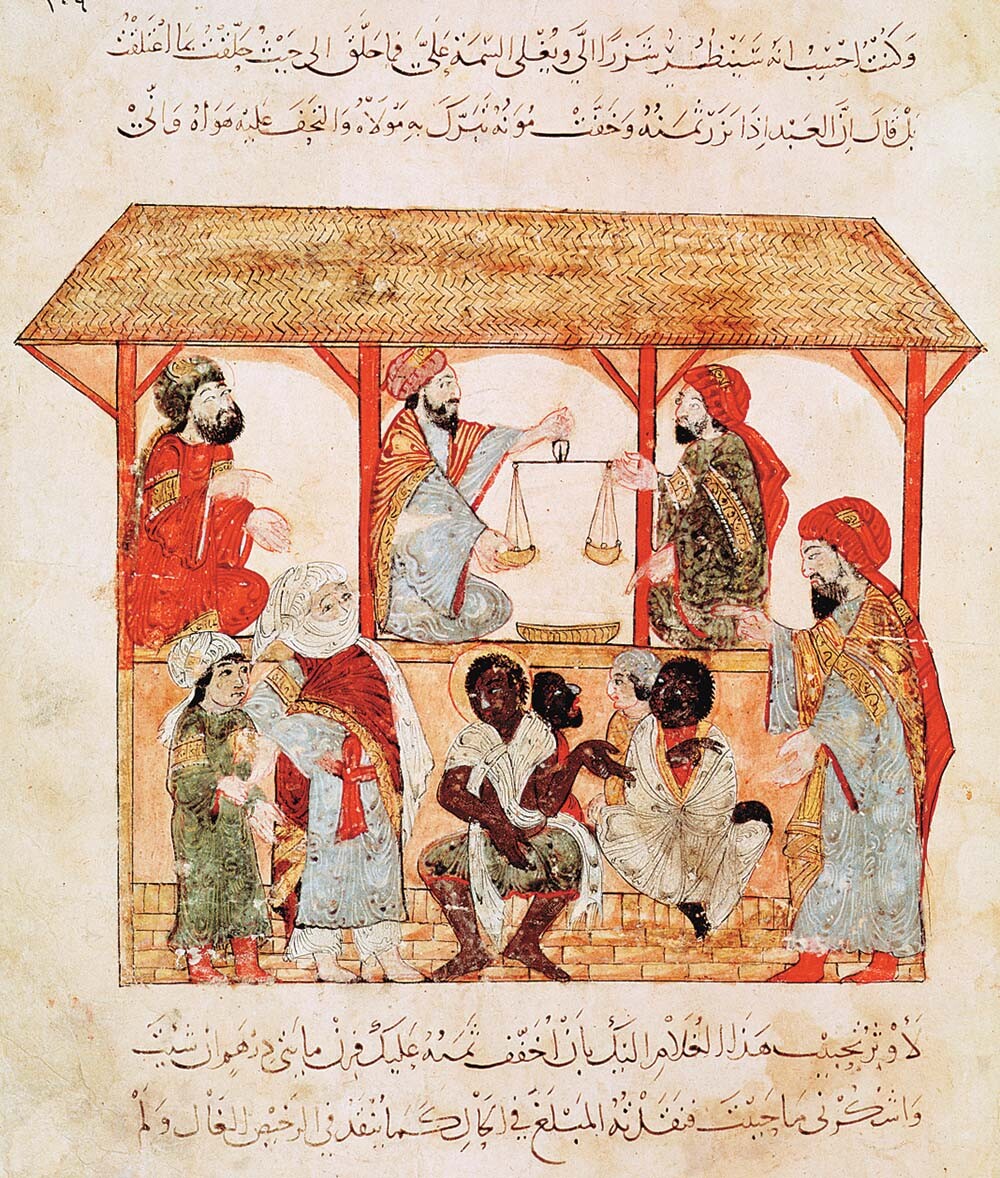

A painting of a covered marketplace with several enslaved people up for auction in the center. There are several figures standing near them. Three men sit under the covered marketplace, one of whom holds a scale in front of him. There is script below the illustration.

Enslaved African people were as valuable as African gold in shipments to Indian Ocean as well as Mediterranean markets. After Islam spread into Africa and sailing techniques improved, the slave trade across the Sahara Desert and Indian Ocean boomed. Although the Quran mitigated the severity of slavery by requiring Muslim enslavers to treat their workers kindly and praising those who freed the enslaved, the African slave trade flourished under Islam. Africans became enslaved either by being taken as prisoners of war or by being sold into slavery as punishment for committing a crime. Enslaved people might have worked as soldiers, seafarers on dhows, domestic servants, or plantation workers. Yet in this era, plantation slave labor, like that which later became prominent in the Americas in the nineteenth century, was the exception, not the rule.

The Americas: Worlds Apart

During this period, the Americas were untouched by the connections reverberating across Afro-Eurasia. Other than limited Viking contact with North America (see Chapter 9), navigators still did not cross the large oceans that separated the Americas from other lands. Yet even here, commercial and expansionist impulses fostered closer contact among peoples who lived in the Western Hemisphere.

More information

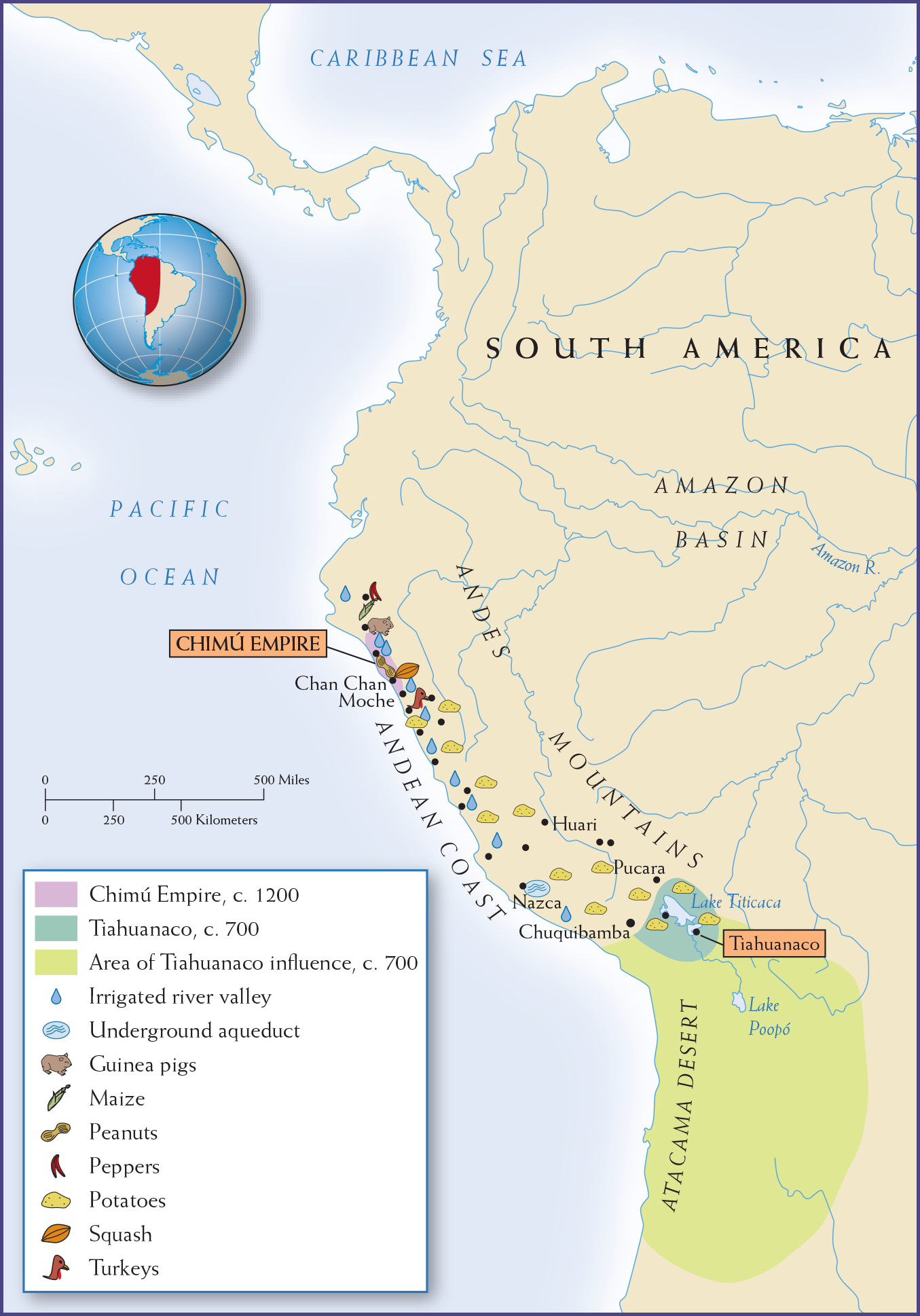

Map 10.9 is titled Andean States, c. 700-1400 C E. The map shows the far western portion of South America, including the Chimu Empire, Tiahuanaco, the area of its influence, the location of irrigated river valleys and underground aqueducts, guinea pigs, turkeys, and crops (maize, peanuts, peppers, potatoes, squash). The city of Tiahuanaco, circa 700 is next to Lake Titicaca. The area of Tiahuanaco’s influence continues south of Lake Titicaca and goes over most of the Atacama Desert. The Chimu Empire, circa 1200, is northeast of Tiahuanaco and lies on the Pacific coast toward the northern part of the Andes Mountains. Irrigated river valleys follow the Andean Coast, an underground aqueduct is near Nazca potatoes follow the Andean Coast but extend inland to Tiahuanaco, and guinea pigs, maize, peanuts, peppers, squash, and turkeys are all concentrated in the area of Chimu.

MAP 10.9 | Andean States, c. 700–1400 CE

Although the Andes region of South America was isolated from Afro-Eurasian developments before 1500, it was not stagnant. Indeed, political and cultural integration brought the peoples of this region closer together.

- Where are the areas of Chimú Empire and Tiahuanaco influence on the map?

- What was the ecology and geography of each region, and how might that have shaped each region’s development?

- From what crops and animals did the Chimú and Tiahuanaco benefit?

ANDEAN STATES OF SOUTH AMERICA Growth and prosperity in the Andean region gave rise to South America’s first empire. The Chimú Empire developed early in the second millennium in the fertile Moche Valley bordering the Pacific Ocean. (See Map 10.9.) Ultimately, the Moche people expanded their influence across numerous valleys and ecological zones, from pastoral highlands to rich valley floodplains to the fecund fishing grounds of the Pacific coast. As their geographic reach expanded, so did their wealth.

More information

An aerial view of the remains of Chan Chan. The remains of the city stretch out into the distance. There are many shorter stone walls within the city ruins and some taller stone walls in the distance. There are several awnings in the left section of the city.

The Chimú economy succeeded because it was highly commercialized. Based in agriculture, complex irrigation systems turned the arid coast into a string of fertile oases capable of feeding an increasingly dispersed population. Cotton became a lucrative export to distant markets along the Andes. Parades of llamas and porters lugged these commodities up and down the steep mountain chains that form the spine of South America. A well-trained bureaucracy oversaw the construction and maintenance of canals, and a hierarchy of provincial administrators watched over commercial hinterlands.

The Chimú Empire’s biggest city was Chan Chan, which had been growing ever larger since its founding around 900 CE. By the time the Chimú Empire was thriving, Chan Chan’s core population had reached 30,000 inhabitants. A sprawling walled metropolis covering nearly 10 square miles, with extensive roads circulating through its neighborhoods, Chan Chan boasted ten huge palaces at its center. Protected by thick walls 30 feet high, these opulent residence halls symbolized the rulers’ power. Within the compound, emperors erected burial complexes for storing their accumulated riches: fine cloth, gold and silver objects, splendid Spondylus shells, and other luxury goods. Around the compound spread neighborhoods for nobles and artisans; farther out stood rows of commoners’ houses. The Chimú regime, centered at Chan Chan, lasted until Inca armies invaded in the 1460s and incorporated the Pacific state into their own immense empire.

TOLTECS IN MESOAMERICA Additional hubs of regional trade developed farther north in the Americas. By 1000 CE, Mesoamerica had seen the rise and fall of several complex societies, including Teotihuacán and the Maya (see Chapter 8). Caravans of porters bound the region together, working the intricate roads that connected the coast of the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific and the southern lowlands of Central America to the arid regions of modern Texas. (See Map 10.10.) The Toltecs filled the political vacuum left by the decline of Teotihuacán and tapped into the commercial network radiating from the rich valley of central Mexico.

The Toltecs grew to dominate the valley of Mexico between 900 and 1100 CE. They were a combination of migrant groups, farmers from the north and refugees from the south fleeing the strife that followed Teotihuacán’s demise. These migrants settled northwest of Teotihuacán as the city waned, making their capital at Tula. They relied on a maize-based economy supplemented by beans, squash, as well as dog, deer, and rabbit meat. Their rulers made sure that enterprising merchants provided them with status goods such as ornamental pottery, rare shells and stones, and precious skins and feathers.

More information

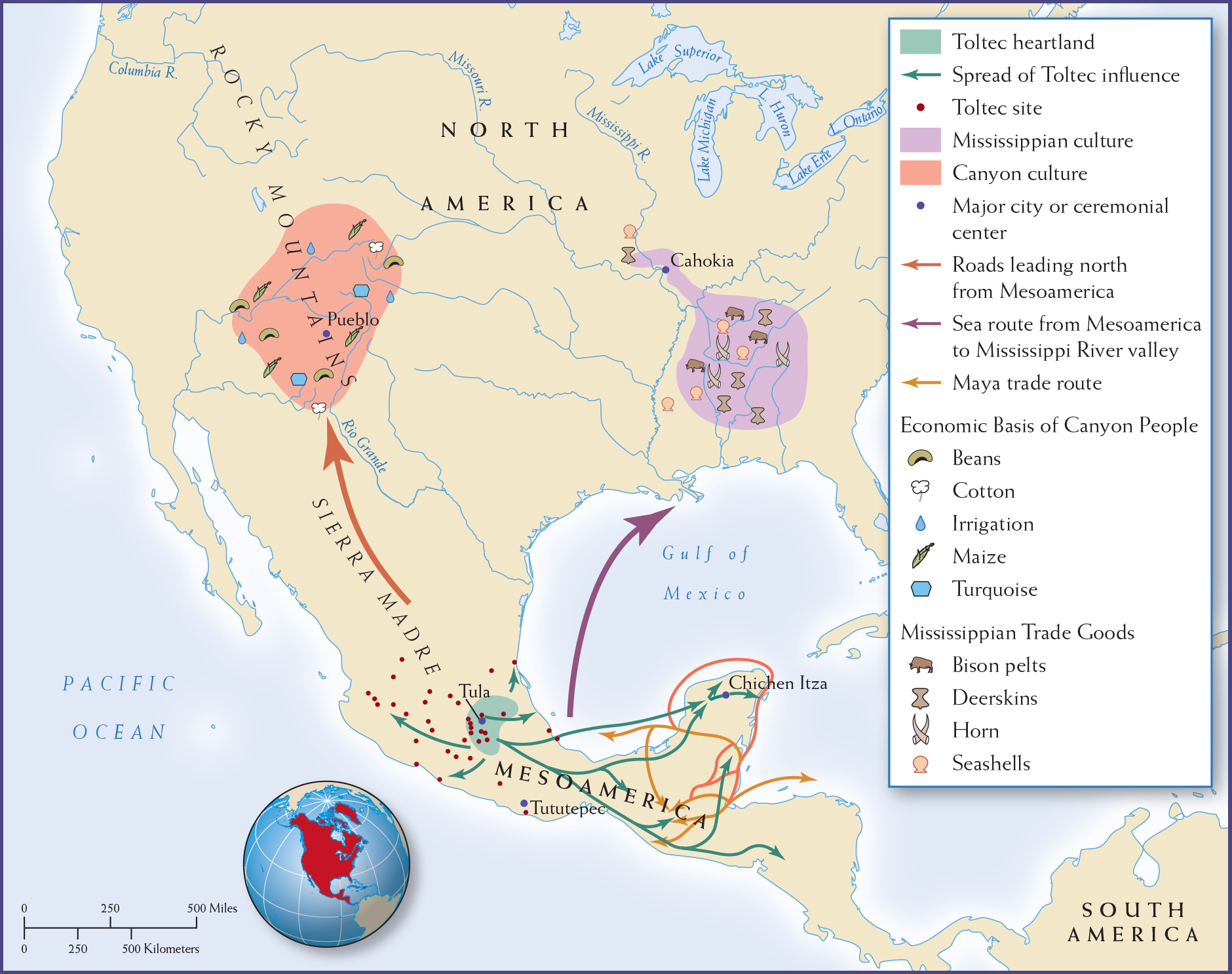

Map 10.10 is titled Commercial Hubs in Mesoamerica and North America, 1000 C E. The map shows the Toltec heartland (around Tula in central present-day Mexico) and nearby sites, as well as the spread of its influence. From this hub, there are three trade routes: the Mayan trade route, the road leading north to the Canyon Culture, and the sea route leading to the Mississippi River valley. The Mayan trade route travels around the southern tip of present-day Mexico. The sea route to the Mississippi River valley travels north across the Gulf of Mexico. The road leading north travels through the Sierra Madre toward the Canyon Culture. The Mississippian Culture lies inland, north of the mouth of the Mississippi River and south of Cahokia. The Mississippi trade goods are bison pelts, deerskin, horns, and seashells. The Canyon Culture is centered on the Rocky Mountains around Pueblo. The economic basis of the Canyon people is beans, cotton, irrigation, maize, and turquoise. Major cities or ceremonial centers include Tututepec, Chichen Itza, Pueblo, and Cahokia.

MAP 10.10 | Commercial Hubs in Mesoamerica and North America, 1000 CE

Both Cahokia and Tula were commercial hubs of vibrant regional trade networks.

- What routes linked Tula and the Toltecs with other regions?

- What goods circulated in the regions of Pueblo and Cahokia?

- Based on the map, what appear to be some of the differences between Canyon culture, Mississippian culture, and the Toltecs?

Tula was at once commercial hub, political capital, and ceremonial center. While its layout differed from Teotihuacán’s, many features revealed borrowings from other Mesoamerican peoples. Temples consisted of giant pyramids topped by colossal stone soldiers; ball courts where subjects and conquered peoples alike played their ritual sport were found everywhere. The architecture and monumental art reflected the mixed and migratory origins of the Toltecs in a combination of Maya and Teotihuacáno influences. At its height, the Toltec capital teemed with 60,000 people, a huge metropolis by contemporary European standards (if small by Song Chinese and Abbasid standards).

More information

A photo of a Toltec Temple. It is a stepped pyramid that is four levels high. There are stone columns that stand at the top of the pyramid. More stone columns stand at the foot of the pyramid and around it. There are mountains in the distance.

CAHOKIANS IN NORTH AMERICA As in South America and Mesoamerica, cities took shape at the hubs of trading networks across North America. The largest was Cahokia, along the Mississippi River near modern-day East St. Louis, Illinois. A city of about 15,000, it approximated the size of London at the time. Farmers and hunters had settled in the region around 600 CE, attracted by its rich soil, its woodlands that provided fuel and game, and its access to trade via the Mississippi. Eventually, fields of maize and other crops fanned out toward the horizon. The hoe replaced the trusty digging stick, and satellite towns erected granaries to hold the growing harvests.

By 1000 CE, Cahokia was an established commercial center for regional and long-distance trade. The hinterlands produced staples for Cahokia’s urban consumers, and in return its crafts rode inland on the backs of porters and to distant markets in canoes. Woven fabrics and ceramics from Cahokia were exchanged for mica from the Appalachian Mountains, seashells and sharks’ teeth from the Gulf of Mexico, and copper from the upper Great Lakes. Cahokia became more than an importer and exporter: it served as the principal exchange hub for an entire regional network trading in salt, tools, pottery, woven stuffs, jewelry, and ceremonial goods.

Dominating Cahokia’s urban landscape were enormous earthen mounds of sand and clay (thus the Cahokians’ nickname of “mound people”). It was from these artificial hills that the people honored spiritual forces. Building these types of structures without draft animals, hydraulic tools, or even wheels was labor-intensive, so the Cahokians recruited neighboring people to help. A palisade around the city protected the metropolis from marauders.

Ultimately, Cahokia’s success bred its downfall. As woodlands fell to the axe and the soil lost its nutrients, timber and food became scarce. In contrast to the sturdy dhows of the Arabian Sea and the bulky junks of the China seas, Cahokia’s river canoes could only carry limited cargoes. Cahokia’s commercial networks thus met their technological and environmental limits. When the creeks that fed its water system could not keep up with demand, engineers changed their course, but to no avail. By 1350 the city was practically empty. But Cahokia represented the growing networks of trade and migration in North America and the ability of North Americans to organize vibrant commercial societies.

Two forces contributed to greater integration in sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas from 1000 to 1300 CE: commercial exchange (of salt, gold, ivory, and enslaved people in sub-Saharan Africa and shells, pottery, textiles, and metals in the Americas) and urbanization (at Jenne, Timbuktu, and Great Zimbabwe in sub-Saharan Africa and at Chan Chan, Tula, and Cahokia in the Americas). By 1300, trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean exchange had brought Africa into full-fledged Afro-Eurasian networks of exchange and, as we will see in Chapter 12, transatlantic exchange would soon connect the Americas into a truly global network.

Glossary

- Mali Empire

- West African empire, founded by the legendary king Sundiata in the early thirteenth century. It facilitated thriving commerce along routes linking the Atlantic Ocean, the Sahara, and beyond.

- Chimú Empire

- South America’s first empire, centered at Chan Chan, in the Moche Valley on the Pacific coast from 1000 through 1470 CE, whose development was fueled by agriculture and commercial exchange.

- Toltecs

- Mesoamerican peoples who filled the political vacuum left by Teotihuacán’s decline; established a temple-filled capital and commercial hub at Tula.

- Cahokia

- Commercial city on the Mississippi River for regional and long-distance trade of commodities such as salt, shells, and skins, and of manufactured goods such as pottery, textiles, and jewelry; marked by massive artificial hills, akin to earthen pyramids, used to honor spiritual forces.