THE BIG PICTURE

What crises affected fourteenth-century Afro-Eurasia and what was the range of responses to those crises?

THE BIG PICTURE

What crises affected fourteenth-century Afro-Eurasia and what was the range of responses to those crises?

Although the Mongol invasions overturned the political systems that they encountered, the plague devastated society itself. The pandemic killed millions, disrupted economies, and threw communities into chaos. Rulers could explain to their people the assaults of “barbarians,” but it was much harder to make sense of an invisible enemy. Nonetheless, in response to the upheaval, surviving rulers and their regimes moved to reorganize their states. By making strategic marriages and building powerful armies, these rulers enlarged their territories, formed alliances, and built dynasties.

The Black Death

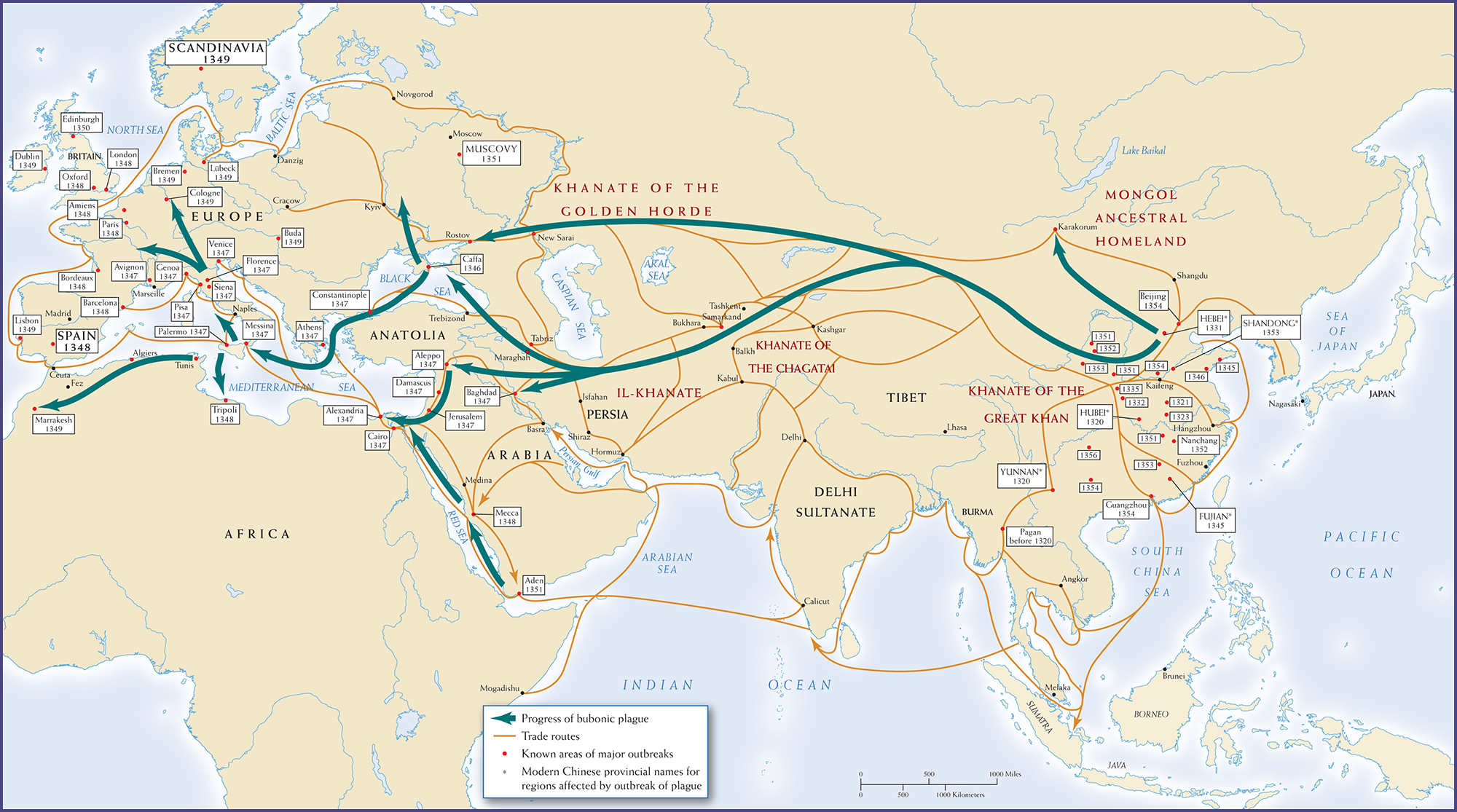

The spread of the Black Death was the fourteenth century’s most significant historical development. (See Map 11.1.) Originating in Inner Asia, the disease afflicted peoples from China to Europe and killed 25 to 65 percent of infected populations.

How did the Black Death move so far and so fast? One explanation may lie in climate changes. The cooler climate of this period—scholars refer to a “Little Ice Age”—may have weakened populations and left them vulnerable to disease. In Europe, for instance, beginning around 1310, harsh winters and rainy summers shortened growing seasons and ruined harvests. Exhausted soils could no longer supply the crops that expanding urban and rural populations required; at the same time, nobles squeezed the peasantry through taxation in an effort to maintain their luxurious lifestyles. The ensuing famine lasted from 1315 to 1322, during which time millions of Europeans died, either of starvation or from diseases against which the malnourished population had little resistance. Climate change and famine had thus crippled populations on the eve of the Black Death. Climate change also spread drought across central Asia, where bubonic plague had lurked for centuries. So when steppe peoples migrated in search of new pastures and herds, they carried the germs with them and into contact with more densely populated agricultural communities. Rats also joined the exodus from the arid lands and transmitted fleas to other rodents, which then carried the disease to humans.

The resulting epidemic was terrifying, simply because its causes were unknown. Infected victims died quickly—sometimes overnight—and in agony, coughing up blood and oozing pus and blood from black sores the size of eggs.

But it was the trading network that spread the pathogens across Eurasia into famine-struck western Europe. This wider Eurasian population was vulnerable because its members had no immunity to the disease. The first outbreak in a heavily populated region occurred in southwestern China during the 1320s. From there, the disease spread through China and then continued its death march westward along the major trade routes. Many of these routes terminated at the Italian port cities, where ships with dead and dying people aboard arrived in 1347. From there, what Europeans called the Pestilence or the Great Mortality engulfed the western end of the landmass. Societies in China, the Muslim world, and Europe suffered the disastrous effects of the Black Death.

Map 11.1 is titled The Spread of the Black Death. The map shows trade routes, progress of the bubonic plague, known areas of major outbreaks, and modern Chinese provincial names for regions affected by outbreak of plague. Trade routes run in many directions through the Khanate of the Great Khan, Delhi Sultanate, Il-Khanate, Khanate of the Golden Horde, Arabia, and Europe, and the plague followed many of these same routes. The plague started in Pagan before 1320. From there it spread to Yunnan in 1320, Hubei in 1320, Hebei in 1331, Fuhan in 1345 and through most of the Khanate of Great Khan from 1320 to 1350. It then spread north to the Mongol ancestral homeland and the city Karakorum. It also spread west via the Silk Road to the Khanate of Chatagai. It then went north through the Khanate of the Golden Horde to New Sarai and Rostov. It also went south from the Golden Horde through Samarkand to Baghdad in 1347, as well as north to Tabriz and Caffa on the Black Sea in 1346. It also went to Aleppo, Damascus, Jerusalem, Cairo, and Alexandria in 1347. It also reached Mecca in 1348 and Aden in 1351. From Caffa, the plague moved north towards Muscovy in 1351. It also went south to Constantinople, Athens, and then Messina in Italy in 1347. From there it went south to Tripoli in 1348 and Tunis, Algiers, and Marrakesh in 1349. The plague also moved north to Siena, Florence, Pisa, Genoa, Venice, and Avignon in 1347. Bordeaux, Paris, Amiens, London, Oxford, and Barcelona had outbreaks in 1348. Lisbon, Dublin, Cologne, Bremen, Lubeck, Buda, and Scandinavia had outbreaks in 1349.

A painting of a person with the plague in bed. There are several people around him holding their noses. The patient is shirtless and looks gaunt. A physician wearing long robes holds an object up to his nose with one hand and holds the wrist of the patient with the other. A child wearing a dress, holding a bucket, and covering her nose stands to his left. A woman wearing a dress and interlacing her fingers in front of her sits to his left. On the other side of the bed a woman holds a cloth to her nose with one hand and holds a bowl in the other. A bearded man wearing a turban stands to her left. A loop of fabric hangs from the ceiling above the patient.

PLAGUE IN CHINA China was ripe for the pandemic. Its population had significantly increased under the Song dynasty (960–1279) and subsequent Mongol rule. But by 1300, hunger and scarcity spread as needed resources were stretched thin. This weakened population was especially vulnerable. For seventy years, the Black Death ravaged China, reduced the size of the already small Mongol population, and shattered the Mongol rulers’ claim to a mandate from heaven. In 1331, plague may have killed 90 percent of the population in Bei Zhili (modern Hebei) Province. From there it spread through other provinces, reaching Fujian and the coast at Shandong. By the 1350s, most of China’s large cities had already suffered through severe outbreaks.

Even as the Black Death was engulfing China, bandit groups and dissident religious sects undercut the power of the last Mongol Yuan rulers. Popular religious movements warned of impending doom. Most prominent was the Red Turban movement, which blended China’s diverse cultural and religious traditions, including Buddhism, Daoism, and other faiths. Its leaders emphasized strict dietary restrictions, penance, and ceremonial rituals while making proclamations that the world was drawing to its end.

CORE OBJECTIVES

ASSESS the impact of the Black Death on China, the Islamic world, and Europe.

PLAGUE IN NORTH AFRICA AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN The plague also devastated parts of the Muslim world, including places in North Africa. The Black Death reached Baghdad by 1347. By the next year, plague overtook Egypt, Syria, and Cyprus, causing as many as 1,000 deaths a day, according to a Tunisian report. Animals, too, were afflicted. One Egyptian writer commented: “The country was not far from being ruined. . . . One found in the desert the bodies of savage animals with the bubos under their arms. It was the same with horses, camels, asses, and all the beasts in general, including birds, even the ostriches.” In the eastern Mediterranean, plague left many polities close to political and economic collapse. The great Arab historian Ibn Khaldûn (1332–1406), who lost his mother and father and a number of his teachers to the Black Death in Tunis, underscored the desolation. “Cities and buildings were laid waste, roads and way signs were obliterated, settlements and mansions became empty, dynasties and tribes grew weak,” he wrote. “The entire world changed.”

PLAGUE IN EUROPE In Europe, the Black Death made landfall on the Italian Peninsula; then it seized France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, and England. Overcrowded and unsanitary cities were particularly vulnerable. All levels of society—the poor, craftspeople, aristocrats—were at risk, although flight to the countryside offered some protection from infection. Nearly 50 million of Europe’s 80 million people perished between 1347 and 1351. After 1353, the epidemic waned, but the plague returned every seven years or so for the rest of the century and sporadically through the fifteenth century. Consequently, the European population continued its decline, until by 1450 many areas had only one-quarter the number of people that they did a century earlier.

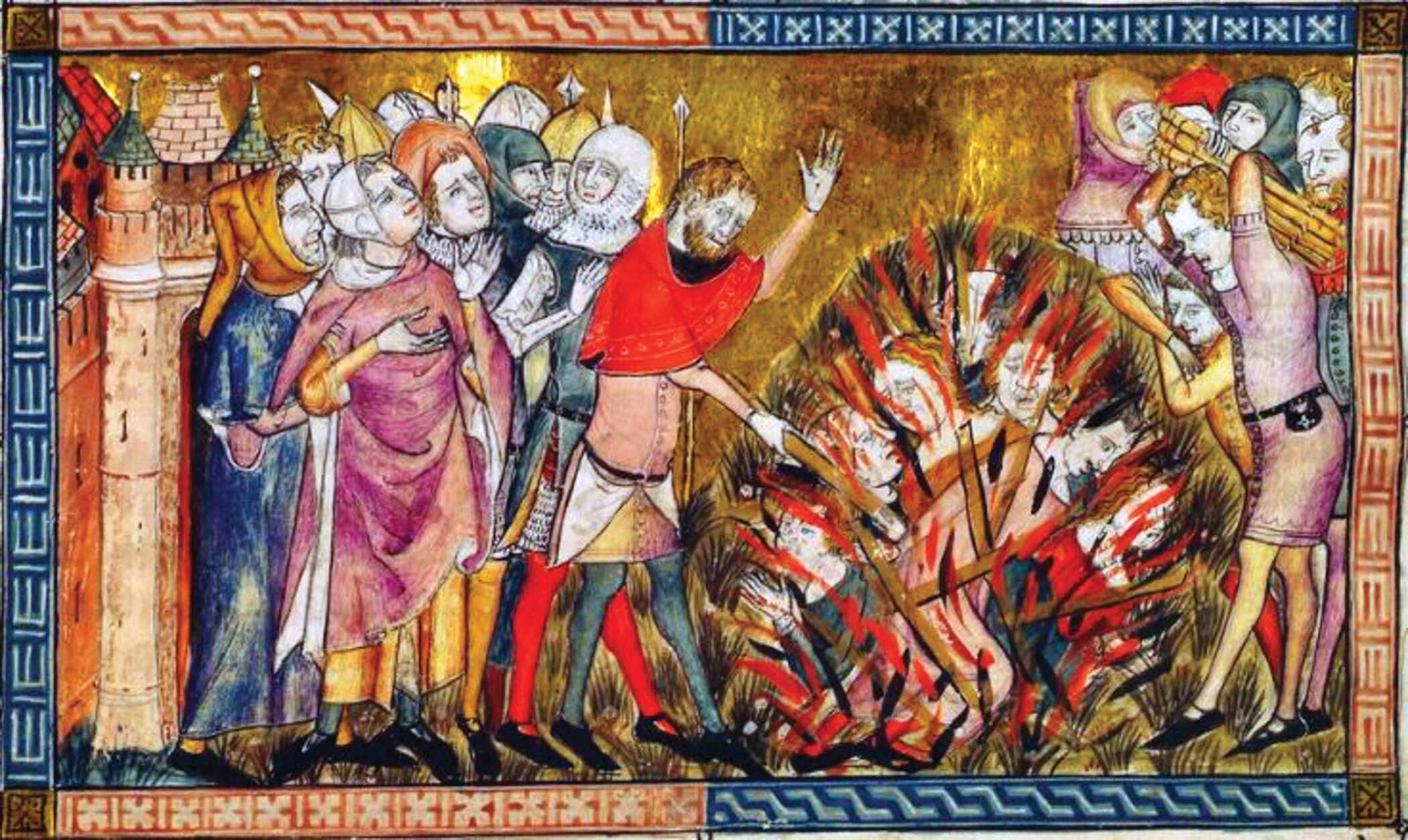

In the face of the Black Death, some Europeans turned to debauchery, determined to enjoy themselves before they died. Others, especially in urban settings in Flanders, the Netherlands, and parts of Germany, claimed to find God’s grace outside what they saw as a corrupt Catholic Church. Semimonastic orders like the Beghards and Beguines, which had begun in the century or so before the plague, expanded in its wake. These laypeople (unordained men and women) argued that people should trust their own “interior instinct” more than the Gospel as then preached. By contrast, the Flagellants were so convinced that man had incurred God’s wrath that they whipped themselves to atone for human sin.

A painting on a manuscript page shows a group of people watching a pile of burning dead bodies. Some of them hold spears. One person holds a flaming torch to the pile and another holds a bundle of wood above their head. Part of a castle is visible behind the group of people on the left side of the painting. There is a decorative border around the painting.

For many who survived the plague, disappointment with the clergy smoldered. Famished peasants resented priests and monks for living lives of luxury. In addition, they despaired at the absence of clergy when they were so greatly needed. While many clerics had perished attending to their parishioners during the Black Death, others had fled to rural retreats far from the ravages of the plague, leaving their followers to fend for themselves.

The Black Death wrought devastation throughout Afro-Eurasia. The Chinese population plunged from around 115 million in 1200 to 75 million or less in 1400, as the result of the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century and the disease and disorder of the fourteenth century. Over the course of the fourteenth century, Europe’s population shrank by more than 50 percent. In the most densely settled Islamic territory—Egypt, located on the African continent—a population that had totaled around 6 million in 1400 was reduced by half. When farmers fell ill with the plague, food production collapsed. Famine resulted, which starved survivors to death. Worst afflicted were the crowded cities, especially their ports. Refugees from urban areas fled their homes, seeking security and food in the countryside. Moreover, the shortage of food and other necessities led to rapidly rising prices, work stoppages, and unrest. Political leaders added to their unpopularity by repressing demands for change. Regimes collapsed everywhere. The Mongol Empire, which had held so much of Eurasia together commercially and politically, collapsed under the weight. As a result, the region was ready for experiments in state building, religious beliefs, and cultural achievements.

“Good Laws and Good Arms”

Starting in the late fourteenth century, residents of connected societies in Afro-Eurasia began the task of reconstructing both their political orders and their trading networks. By then the plague had died down, though it continued to afflict humans for centuries. However, the rebuilding of military and civil administrations—no easy task—also required political legitimacy. With their people deeply shaken by the extraordinary loss of life, rulers needed to revive confidence in themselves and their regimes, which they did by fostering beliefs and rituals that confirmed their rights to rule, while increasing their control over their subjects.

The basis for power was a political institution well known for centuries, the dynasty—a ruling family that passed control from one generation to the next. Like those of the past, new dynasties sought to establish their legitimacy in three ways. First, ruling families insisted that their power derived from a divine calling: Ming emperors in China claimed for themselves what previous dynastic rulers had asserted—the “mandate of heaven”—while European monarchs claimed to rule by “divine right.” From their base in Anatolia, Ottoman warrior-princes asserted that they now carried the banner of Islam. In these ways, ruling households affirmed that God or the heavens intended for them to hold power. Second, leaders attempted to prevent squabbling among potential heirs by establishing clear rules about succession to the throne. Many European states tried to standardize succession by passing titles to the eldest male heir, thus ensuring political stability at a potential time of crisis, but in practice there were countless complications and quarrels. In Islamic states, successors could be designated by the current ruler or elected by the community; here, too, struggles over succession were frequent. Third, ruling families elevated their power through conquest or alliance—by ordering armies to forcibly extend their domains or by marrying their royal offspring to rulers of other states or members of other elite households, a technique widely practiced in Europe. Once it established legitimacy, the typical royal family would consolidate power by enacting coercive laws and punishments and sending emissaries to govern distant territories. A ruling family would also establish standing armies and new administrative structures to collect taxes and to oversee building projects that proclaimed royal power.

As we will see in the next three sections of this chapter, the innovative state building that followed the plague’s devastating wake would not have been as successful had it not drawn on older traditions. The peoples of the Islamic world held fiercely to their religion as successor states, notably the Ottoman Empire, absorbed numerous Turkish-speaking groups. In Europe, a cultural flourishing based largely on ancient Greek and Roman models gave rise to thinkers who proposed new views of governance. The Ming renounced the Mongol expansionist legacy and emphasized a return to Han rulership, consolidating control of Chinese lands and concentrating on internal markets rather than overseas trade. Many of these regimes lasted for centuries, long enough to set deep roots for political institutions and cultural values that molded societies long after the Black Death.