THE BIG PICTURE

What were the major steps in the integration of global trade networks in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries?

THE BIG PICTURE

What were the major steps in the integration of global trade networks in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries?

Mercantilism

In spite of the worldwide trauma brought on by the plunge in temperatures, global trade flourished in the seventeenth century. Increasing economic ties brought new places and products into world markets. (See Current Trends in World History: Stimulants, Sociability, and Coffeehouses.) Closer economic contact enhanced the power of certain states and destabilized others. It bolstered the legitimacy of England and France, and it prompted strong local support of new rulers in Japan and parts of sub-Saharan Africa. But elsewhere, linkages led to civil wars and social unrest. In the Ottoman state, outlying provinces slipped from central control; the Safavid regime foundered and then collapsed; the Ming dynasty imploded and gave way to the Qing. In India, rivalries among princes and merchants eroded the Mughals’ authority, compounding the instability caused by peasant uprisings.

The plunge in temperatures also forced people from marginal agricultural lands into the cities. The world had never experienced such massive urbanization: 2.5 million Japanese lived in cities, roughly 10 percent of the population, and in Holland over 200,000 lived in ten cities close to Amsterdam. But city officials were ill equipped to deal with the influx. Disease swept through overcrowded houses, and fire ravaged whole districts. London had an excess of 228,000 deaths over births yet continued to grow through in-migration. Hardly an escape from rural poverty, cities had inordinately high mortality rates.

CORE OBJECTIVES

EXPLAIN the significance of European consumption of goods (like tobacco, textiles, and sugar) for the global economy.

Transformations in global relations began in the Atlantic, where the extraction and shipment of gold and silver siphoned wealth from the Americas to Afro-Eurasia. (See Map 13.1.) Mined mainly by coerced Indigenous people and delivered into the hands of merchants and monarchs, silver from the Andes and Mesoamerica boosted the world’s supply of money and spurred trade. During the boom years of the sixteenth century, the increased supply of silver inflated prices. But there could also be sharp contractions, especially after 1620, which deflated prices and led to shortages. Then, a new boom began after 1690: new silver veins opened in Mexico and a gold rush made Brazil the world’s largest producer of that precious metal. For societies that depended on these metals for their money supply, the ups and downs of mining output, resulting in inflation and deflation, were at times severely disruptive.

While armies, travelers, and missionaries were breaching the world’s main political and cultural barriers, it was commodities that had unsung effects on everyday lives. The rise of world commodities transformed production and consumption. Ruling elites struggled to control and to curtail the desire of their populations to dress themselves in fine garments, to possess jewelry, and to consume satisfying food and drink no matter where these products came from. The history of commodities is a central concern for world historical research: to make products for other peoples’ consumption meant crossing cultural barriers and connecting peoples over long distances. As the world’s trading networks expanded in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, merchants in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas served as the brokers or the new commodity exchange—at a scale that would have made the Silk Road traders green with envy. By far the most popular commodities were a group of stimulants: coffee, cocoa, sugar, tobacco, and tea. These were not just stimulating, they were addicting. Previously, many of these products had been grown in isolated parts of the world: the coffee bean in Yemen, tobacco and cocoa in the New World, and sugar in Bengal. Yet, by the seventeenth century, in nearly every corner of the world, the well-to-do began to congregate in coffeehouses, consuming these new products and engaging in sociable activities. While new consumption habits laced the world together, globalized commodity frontiers expanded commercial production across the tropics.

Coffeehouses everywhere served as locations for social exchange, political discussions, and business activities. Yet they also varied from cultural area to cultural area, reflecting the values of the societies in which they arose.

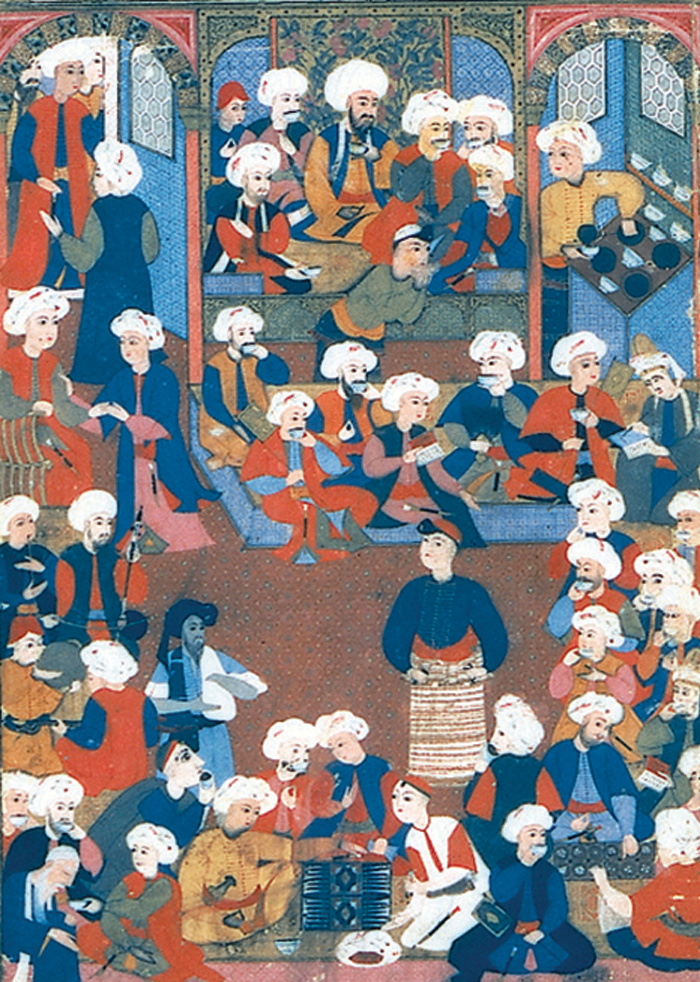

The coffeehouse first appeared in Islamic lands late in the fifteenth century. As coffee consumption caught on among the wealthy and leisured classes in the Arabian Peninsula and the Ottoman Empire, local growers protected their advantage by monopolizing its cultivation and sale and refusing to allow any seeds or cuttings from the coffee tree to be taken abroad. Despite some religious opposition, coffee spread into Egypt and throughout the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth century. Ottoman bureaucrats, merchants, and artists assembled in coffeehouses to trade stories, read, listen to poetry, and play chess and backgammon. Indeed, so deeply connected were coffeehouses with literary and artistic pursuits that people referred to them as schools of knowledge.

From the Ottoman territories, the culture of coffee drinking spread to western Europe. The first coffeehouse in London opened in 1652, and within sixty years the city claimed no fewer than 500 such establishments. In fact, the Fleet Street area of London had so many that the English essayist Charles Lamb commented, “[T]he man must have a rare recipe for melancholy who can be dull in Fleet Street.” Although coffeehouses attracted people from all levels of society, they especially appealed to the new merchant and professional classes as locations where stimulating beverages like coffee, cocoa, and tea promoted lively conversation without the inebriating effects of alcohol—and spared patrons the reputational toll of bawdy taverns. However, some opponents claimed that excessive coffee drinking destabilized the thinking processes; the narcotic effects of caffeine, it was said, might even promote conversions to Islam. But consumer demand won out: the pleasures of coffee, tea, and cocoa prevailed. These bitter beverages in turn required liberal doses of the sweetener sugar. A smoke of tobacco topped off the experience. In this environment of pleasure, patrons of the coffeehouses indulged their addictions, engaged in gossip, conducted business, and talked politics.

Many people gathered together in a banquet hall while kneeling and standing around with coffee. About forty men, almost all wearing white turbans, are seated in several rows while servers bring them coffee. There are several arches with patterns on the tops in the back of the hall.

An illustration shows coffee drinkers sitting at two tables in an English coffeehouse. In the illustration, almost all wear long wigs, while half have black hats. Some sit, others stand, one drinks, another pours, and a third raises his cup in a toast. A portrait and a landscape painting are hung on the wall behind the tables.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

Hattox, Ralph S., Coffee and Coffeehouses: The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East (1985).

Pendergrast, Mark, Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World (2010).

Overall, a rising money supply and new institutions like stock markets and lending houses spurred global trade. American exports were so lucrative for Spain and Portugal that other European powers wanted a share of the bounty, so they too launched colonizing ventures in the New World. Although these latecomers found few precious metals, they devised other ways to extract wealth, for the Americas had fertile lands on which to cultivate sugarcane, cotton, tobacco, indigo, and rice.

If silver quickened the pace of global trade, sugar transformed diets. First domesticated in Polynesia, sugar rarely appeared in European diets before the American plantations started exporting it. Previously, Europeans had used honey as a sweetener, but they soon became insatiable consumers of sugar. Between 1690 and 1790, Europe imported 12 million tons of sugar—approximately 1 ton for every African enslaved in the Americas.

Extracting wealth from colonies gave rise to a new economic model to govern long-distance relations between societies. No matter what products they supplied, colonies were supposed to provide wealth for their “mother countries”—according to the economic theory of mercantilism, which drove European empire builders. Hitherto, conquests aimed to plunder the defeated or to claim tribute. But the economic integration of the Americas—the peoples and lands—gave rise to policies and concepts that aimed to keep wealth flowing from one society to another in large sums year after year, generation after generation. The term mercantilism describes a system that saw the world’s wealth as fixed, meaning that any one country’s wealth came at the expense of other countries. Mercantilism further assumed that overseas possessions existed solely to enrich European motherlands. Lucrative colonies were like magnets for competitors who wanted in on the action. Empires were therefore in a constant struggle to shut out rivals and interlopers, lest foreign traders drain precious resources from an empire’s exclusive domain. The result was a vicious cycle: extraction allowed European states to grow rich while the feud to protect extraction rackets generated unceasing wars between rivals. Ultimately, mercantilists believed, as did the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), that “wealth is power and power is wealth.”

Map 13.1 is titled, Trade in Silver and other Commodities, 1650-1750. The map shows Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, and Dutch territories, as well as Anglo-French contested areas, commodities, silver flow, trade route, and battles. Spanish territories include the Viceroyalty of New Spain and Mexico in North America and the Viceroyalties of Granada and Peru in South America, as well as the Philippines. Portuguese territories include the Viceroyalty of Brazil in South America the area around Luanda in West Africa, and enclaves from Mogadishu to Sofala along the coast of East Africa. English territory includes Rupert’s Land, the Thirteen Colonies, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland in North America, as well as small enclaves around Accra, Lagos, and Cape Town in Africa and near Calcutta in India. French territories include Louisiana and New France in North America, as well as a sliver of Surinam. Dutch territory includes the rest of Surinam, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Timor, and part of New Guinea. Silver flows out of Peru and Mexico and across the world, traveling to Europe, Southwest Asia, Africa, and eventually East Asia. Trade routes travel to Europe from India, China, and Southeast Asia, between Europe and North America and the Caribbean, and between Africa and South America. Other commodities traded globally included silk and spices (from China); silk, pepper, calico, coffee, and drugs (from India, China, and Southeast Asia); indigo from India; slaves from Africa; tobacco and sugar from Brazil; tobacco, rice, furs, meat, timber, grain indigo and Texas from North America; sugar, gold, diamonds, calico, coffee, and taxes from South America; and iron, copper, textiles, cutlery, firearms and manufactures from Europe. The battle of Plassey occurred in Bengal.

The mercantilist system required an alliance between the state and its merchants. Mercantilists understood economics and politics as interdependent, with the merchant needing the monarch to protect his interests and the monarch relying on the merchant’s trade to enrich the state’s treasury. Chartered companies, such as the (English) Virginia Company and the Dutch East India Company, were the most visible examples of the collaboration between the state and the merchant classes. European monarchs awarded these firms monopoly trading rights over vast areas.

CORE OBJECTIVES

DESCRIBE and EXPLAIN the impact of climate change on societies and economies around the globe.

While commerce brought the world together, the global climate entered what is known as the Little Ice Age, which shocked the planet’s survival systems with plunging temperatures and drought. It also happened to coincide with a downturn in New World mining output. The combination was toxic. In some places, the effect of falling temperatures, shorter growing seasons, and irregular precipitation patterns was felt as early as the fourteenth century. But the impact of the Little Ice Age reached farther and deeper in the seventeenth century. What caused this climate change is a matter of debate. Some argue that a combination of low sunspot activity and volcanic eruptions choked the atmosphere and changed ocean currents. Others have argued the reverse—that changing currents altered the pressure on continental shelves, which set off earthquakes and volcanoes. Whatever the case, the results ravaged an interconnected world. What’s more, recent research has revealed that the great dying of Indigenous peoples in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as described in the previous chapter, was a major factor producing the Little Ice Age. The collapse in Indigenous populations cleared the way for a return of trees and bushes to what was once densely tilled land. This created what scientists call a “carbon sink.” The return of forests gave the planet the means to pull vast quantities of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which resulted in the earth trapping less of the sun’s heat. This, in turn, intensified cooling and dried the air. By contrast, this was the reverse of the trend we see today, in which deforestation reduces the planet’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide, leading to warming.

While the seventeenth-century decline in temperatures was especially severe, the cold lasted well into the next century and, in parts of North America, into the nineteenth. Climate change brought mass suffering because harvests failed. Famine spread across Afro-Eurasia. In West Africa, colder and drier conditions saw an advance of the Sahara Desert, leading to repeated famines in the Senegambia region. Timbuktu and the region around the Niger bend suffered their greatest famines in the seventeenth century. It was still so cold in the early nineteenth century that the English novelist Mary Shelley and her husband spent their summer vacation indoors in Switzerland telling each other horror stories, which inspired Shelley to write Frankenstein.

There were also political consequences. As droughts, freezing, and famine spread across Afro-Eurasia, herding societies invaded settled societies. Starving peasants lashed out against their lords and rulers. Violent uprisings owed much to the decline of food production. In the Americas, centuries of plagues had already ripped through Indigenous populations. The long cold snap brought even more suffering. Bitter cold and drought afflicted the Rio Grande basin in northern Mexico, culminating in a deep freeze in 1680. The Puebloans rose up against Spanish rulers in a desperate bid for survival. Tensions between Iroquois and Huron rose in the Great Lakes region of North America. Civil war between Portugal and Spain in Europe wreaked havoc in Iberian colonies and led to invasion and panic. The Ottomans faced a crippling revolt, while in China the powerful Ming regime could not deal with the climate shock. Nomadic warriors invaded, as pastures turned to dust. These Manchurian peoples from beyond the Great Wall installed a new regime, the Qing dynasty. The English philosopher Thomas Hobbes famously wrote in Leviathan (1651) that “man’s natural state . . . was war; and not simply war, but the war of every man against every other man.” “The life of man,” he continued, is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Three large Dutch whaling ships sail in the ocean near many row boats full of people. There are people with long poles on a stretch of icy land in the foreground and two polar bears, one of whom is fighting with one of the people. There are several whales and walruses in the water. There are large icebergs and several more whaling ships in the distance.

The Little Ice Age devastated entire populations. It is hard, however, to separate the victims of starvation from the victims of war, since warfare aggravated starvation and famine contributed to war. But in continental Europe, the Thirty Years’ War carried off an estimated two-thirds of the total population, on par with the impact of the Black Death (see Chapter 11). Elsewhere, estimates were closer to one-third. Not until the twentieth century did the world again witness such extensive warfare.