The Chinese Economy and New World Silver

CORE OBJECTIVES

EXPLAIN the effects of New World silver and increased trade on the Asian empires, and their responses to them.

Asia in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

Global trading networks grew as vigorously in Asia as they did in the Americas. In Asia, however, the Europeans played a minor role. Although they could gain access to Asian markets with American silver, they could not conquer Asian empires or colonize vast portions of the region. Nor were they able to enslave Asian peoples as they had Africans. The Mughal Empire continued to grow, and the Qing dynasty, which had wrested control from the Ming, significantly expanded China’s borders. China remained the richest state in the world, but in some places the balance of power was tilting in Europe’s direction. Not only did the Ottomans’ borders contract, but by the late eighteenth century Europeans had established economic and military dominance in parts of India and much of Southeast Asia.

The Dutch in Southeast Asia

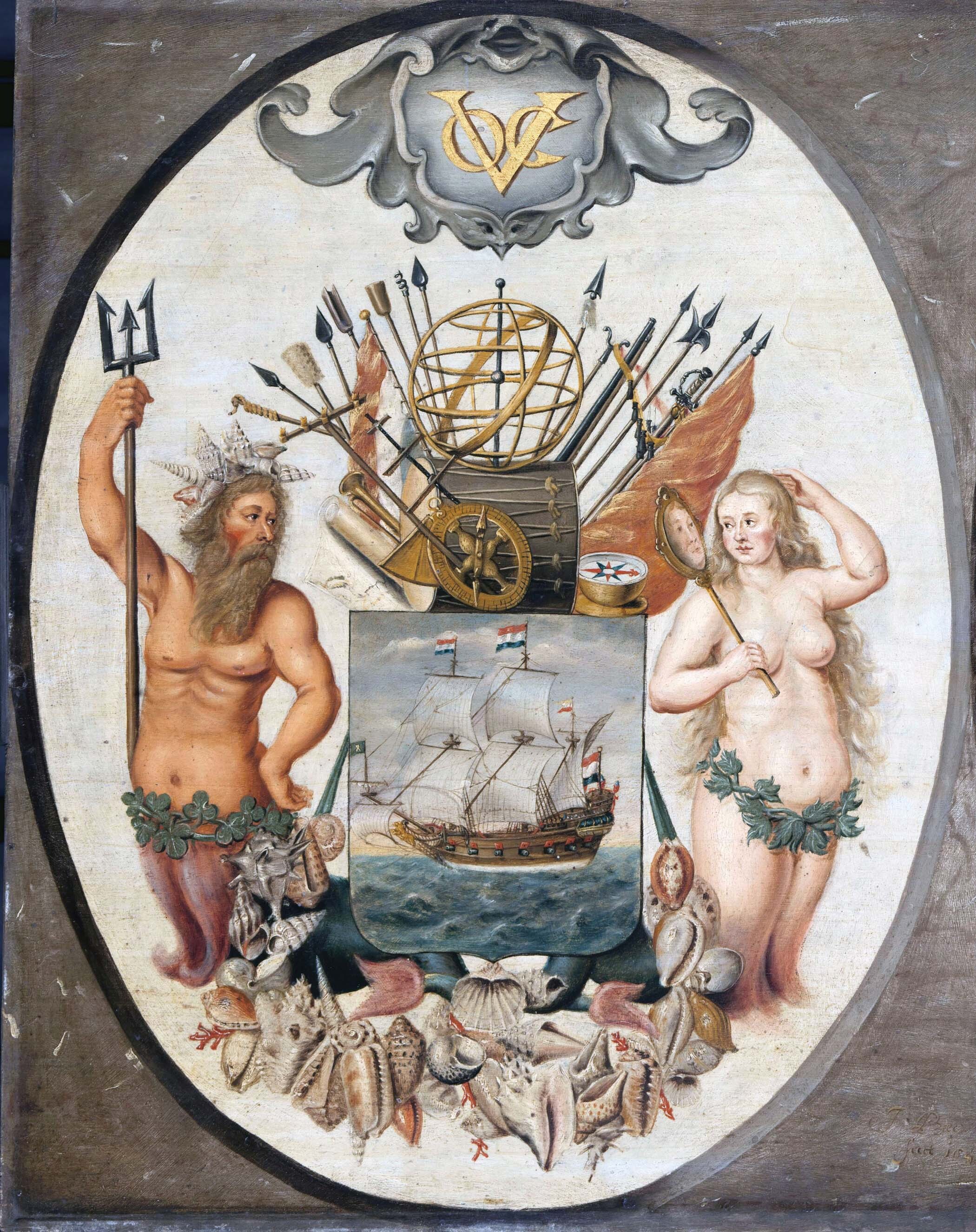

In Southeast Asia, the Dutch already enjoyed considerable influence by the seventeenth century. Although the Portuguese had seized the vibrant port city of Melaka in 1511 and the Spaniards had taken Manila in 1571, neither was able to monopolize the lucrative spice trade. To challenge them, the Dutch government persuaded its merchants to charter the Dutch East India Company (abbreviated as VOC) in 1602. Benefiting from Amsterdam’s position as the world’s most efficient money market, the VOC raised enough capital to build a vast navy. At its peak, the company had 257 ships and employed 12,000 persons. Throughout two centuries it sent ships manned by a total of 1 million men to Asia.

The commercial-military drive created a conquering machine in Southeast Asia to develop extractive economies, akin to Atlantic plantations. Spices, coffee, tea, and teakwood became key exports. (See again Map 13.1.) The company’s objective was to secure a trade monopoly wherever it could, fix prices, and subdue local populations, enslaving them where they could and, where they could not, importing workers from the rest of the region. Under the leadership of Jan Pieterszoon Coen (who once said that trade could not be conducted without war and war could not be conducted without trade), the Dutch swept into the Javanese port of Jakarta in 1619 and took over the nearby Banda Islands two years later. In Banda, the Dutch killed chiefs and enslaved villagers. To clear the land for commercial spice production and to build fortresses and ships, the Dutch ordered forests to be razed. They imposed their own monopolies on vibrant local coastal trading systems. Dutch masters controlled salt, indigo, Japanese copper, timber, opium, and anything else that was tradable. To buy these goods, islanders had to work on Dutch plantations for miserable wages.

Islanders resisted wherever possible, sometimes with the support of Dutch rivals, the English. The people of the Maluku Strait, for instance, objected to the Dutch commercial restrictions and monopoly extraction. They drove the Dutch from their lands, led by their chief Majira from the island of Seram, who wanted to sell his villagers’ cloves directly to Asian merchants. In 1651, Majira rallied his people and went to war, but their arrows and spears were no match for Dutch muskets.

Once ecologically complex, the islands became monocrop (single-crop) plantations. By 1670 the Dutch controlled all of the spice trade from the Maluku islands. Next, the VOC set its sights on pepper. However, the Dutch had to share this commerce with Chinese and English competitors. Moreover, since there was no demand for European products in Asia, the Dutch had to participate more in inter-Asian trade to reduce their need to make payments in precious metals.

More information

A black and white print of Dutch invaders with muskets fighting Maluku warriors with bows and arrows. The bodies of several fallen warriors lay on the ground. Smoke drifts upwards from the muskets of the invaders. There are several trees in the foreground and more trees and a mountain in the background.

Transformations in the Islamic Heartland

Compared with Southeast Asia, the major Islamic empires did not feel such direct effects of European intrusion. They did, however, face internal difficulties, which were exacerbated by trade networks that eluded state control and, in some important instances, by climate change. From its inception, the Safavid Empire had always required a powerful, religiously inspired ruler to enforce Shiite religious orthodoxy and to hold together the realm’s tribal, pastoral, mercantile, and agricultural factions. With a succession of weak rulers and declining tax revenues—aggravated by a series of droughts and epidemics—the state foundered and ultimately collapsed in 1722 (see Chapter 14). The Ottoman and Mughal Empires, in contrast, muddled along.

More information

The V O C coat of arms depicts a painting of a Dutch man-of-war ship with Neptune and Providentia on either side. Above the painting there is pile with nautical instruments, arrows, and a golden globe. There is a pile of various seashells below the painting. Neptune holds a trident, wears a crown of shells, and has a long beard. Providentia holds a mirror and has long flowing hair. Above the illustration there is a crest with the letters V O C.

THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE Climate change hit the eastern Mediterranean earlier than other regions. Fierce cold and endless drought brought famine and high mortality. In 1620, the Bosporus froze over, enabling people to walk from the European side of Istanbul to the Asian side. In lands dependent on floodwaters for their well-being, such as Egypt and Iraq, food was in short supply and death rates skyrocketed. In addition, the import of New World silver led to high levels of inflation and a destabilized economy.

Having attained a high point under Suleiman (see Chapter 11), the Ottoman Empire ceased expanding. After Suleiman’s reign, Ottoman armies and navies tried unsuccessfully to expand the empire’s borders—losing, for example, on the western flank to the European Habsburgs. A series of administrative reforms in the seventeenth century reinvigorated the state, but it never recaptured the power to expand.

Even as the empire’s strength waned, sultans faced a commercially more connected world in the seventeenth century. The introduction of New World silver shook the empire. Although early Ottoman rulers had avoided trade with the outside world, the lure of silver broke through state regulations. Now Ottoman merchants established black markets for commodities that eager European buyers paid for in silver—especially wheat, copper, and wool. Because these exports were illegal, their sale did not generate tax revenues to support the state’s civilian and military administration. Ottoman rulers had to rely on loans of silver from the merchants. Some European royal houses, notably the Dutch and English, would grant those who bankrolled them a say in government, which vastly increased the crown’s credit and ultimately its power. Ottoman sultans, by contrast, feuded with their financiers, which undermined the sultans’ authority.

More silver and budget deficits brought inflation. Prices tripled between 1550 and 1650. Runaway inflation led hard-hit peasants in Anatolia, suffering from bad harvests and increasing taxes, to join uprisings that threatened the state’s stability. A wave of revolt, begun in central Anatolia in the early sixteenth century, continued in fits and starts throughout the century, reaching a crescendo in the early seventeenth century. Known as the Celali revolts, after Shaykh Celali, who had led one of the initial uprisings, the rebellion challenged the sultan’s authority with an army of 30,000 and turned much of Anatolia into a danger zone. Disorder at the center of the empire was accompanied by difficulties in the provinces, where breakaway regimes appeared.

The most threatening of the breakaway pressures occurred in Egypt beginning in the seventeenth century. In 1517, Egypt had become the Ottoman Empire’s greatest conquest. As the wealthiest Ottoman territory, it was an important source of revenue, and its people shouldered heavy tax burdens. The group that asserted Egypt’s political and commercial autonomy consisted of military men, known as Mamluks (Arabic for “owned” or “possessed”), who had ruled Egypt as an independent regime until the Ottoman conquest. Although the Ottoman army had routed Mamluk forces on the battlefield, Ottoman governors in Egypt allowed the Mamluks to remain in place, in a subordinate position. But by the seventeenth century, these military men were nearly as powerful as their ancestors had been in the fifteenth century. Mamluk leaders enhanced their power by aligning with Egyptian merchants and catering to the religious elites of Egypt, the ulama. Turning the Ottoman administrator of Egypt into a mere figurehead, this new provincial elite kept much of the area’s fiscal resources for themselves at the expense not only of the imperial coffers but also of the local peasantry.

Amid new economic pressures and challenges from outlying territories, the Ottoman system also had elements of resilience—especially at the center. Known as the Köprülü reforms (1656–1683), a combination of financial reform and anticorruption measures gave the state a new burst of energy and enabled the military to recover some of its lost possessions. Revenues again increased, and inflation decreased. Fired by revived expansionist ambitions, Istanbul decided to renew its assault on Christianity—beginning with rekindled plans to seize Vienna. Although the Ottomans gathered an enormous force outside the Habsburg capital in 1683, the Ottoman forces ultimately retreated, with both sides suffering heavy losses. Under the treaty that ended the Austro-Ottoman war, the Ottomans lost major European territorial possessions, including Hungary.

Thus, the Ottoman Empire began the eighteenth century with serious economic and environmental challenges. The influx of silver over the course of the seventeeth century had opened Ottoman-controlled lands to trade with the rest of the world, producing breakaway regimes, widespread inflation, social discontent, and conflict between the state and its financiers. The crop shortages and population crises of the Little Ice Age made those problems more difficult to manage.

THE MUGHAL EMPIRE In contrast to the Ottomans’ military reversals, the Mughal Empire reached its height in the seventeenth century. The period saw Mughal rulers extend their domain over almost all of India and enjoy increased domestic and international trade. But they, too, eventually had problems governing dispersed and resistant provinces, where many villages retained traditional religions and cultures and suffered from the effects of the Little Ice Age on their land’s productivity.

More information

A painting of the siege of Vienna. The background shows the city itself, circular and surrounded by walls. It is built near a river. The fighting takes place in the foreground. Soldiers fight on horseback, with bows and arrows, pistols, spears, and swords. Some of the Ottomans ride camels. A group of soldiers hold many banners and smoke floats above the fighting

Before the Mughals, India never had a single political authority. Akbar and his successors had conquered territory in the north (see Chapter 12, Map 12.4), so now the Mughals turned to the south and gained control over most of that region by 1689. As the new provinces provided an additional source of resources, local lords, and warriors, the Mughal bureaucracy grew better at extracting services and taxes. The main source of their wealth came from land rents, aided by increases in productivity, thanks to New World crops like maize and tobacco.

Although the Mughals never undertook overseas expansion themselves, they profited indirectly from Europeans’ increased demand for Indian goods, including a sixfold rise in the English East India Company’s textile purchases. In contrast to European expansion, which was based on the destruction of much Indigenous sovereignty in the Americas or the creation of new states in West Africa to mesh with the new transatlantic slave trade, Mughal expansion relied on confederacies, alliances with neighbors, and tribute taking.

More information

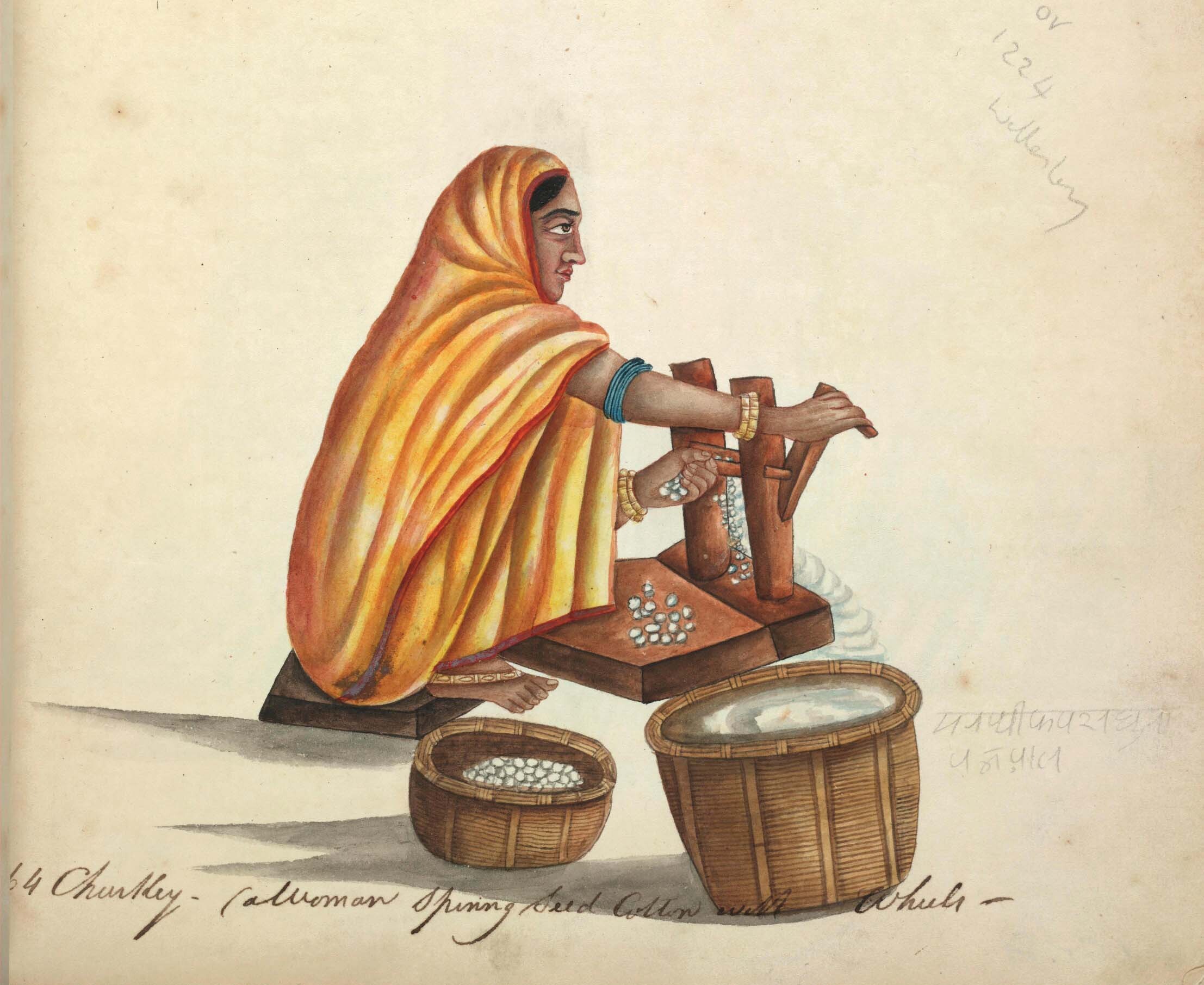

A woman sits sideways and removes seeds from cotton using an old traditional cotton ginning tool. The woman is traditionally dressed with her head covered by a saree. Two baskets are placed near her. There is text at the bottom of the illustration.

Eventually, the Mughals were victims of their own success. More than a century of imperial expansion, commercial prosperity, and agricultural development placed substantial resources in the hands of local and regional authorities. As a result, local warrior elites became more autonomous. By the late seventeenth century, many regional leaders were well positioned to resist Mughal authority. As in the Ottoman Empire, distant provinces began to challenge central rulers. Now the Indian peasants (like their counterparts in Ming China, Safavid Persia, and the Ottoman Empire) capitalized on weakening central authority. Many rose in rebellion, especially when drought and famine hit; others took up banditry.

At this point, Mughal emperors had to accept diminished power over a loose unity of provincial states. Most of these areas accepted Mughal control in name only, administering their own affairs with local resources. Yet India still flourished, and landed elites brought new territories into agrarian production. Cotton, for instance, supported a thriving textile industry as peasant households focused on weaving and cloth production. Much of their production was destined for export as the region deepened its integration into world trading systems.

The Mughals paid scant attention to commercial matters. Local rulers, however, welcomed Europeans into Indian ports. As more European ships arrived, these authorities struck deals with merchants from Portugal and, increasingly, from England and Holland. Some Indian merchants formed trading companies of their own to control the sale of regional produce to competing Europeans; others established intricate trading networks that reached as far north as Russia. Mercantile houses grew richer and gained greater political influence over financially strapped emperors. Thus, even as global commercial entanglements enriched some in India, the effects undercut the Mughal dynasty.

CORE OBJECTIVES

ANALYZE examples of resistance in Southeast Asia and China to the growth of global trade networks.

From Ming to Qing in China

Like India, China prospered in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; but here, too, growing wealth and climate change undermined central control and, in this case, contributed to the fall of a long-lasting dynasty. As in Mughal India, local power holders in China increasingly defied the Ming government. Moreover, because Ming leaders discouraged overseas commerce and forbade travel abroad, they did not reap the rewards of long-distance exchange. Rather, such profits went to traders and adventurers who evaded imperial edicts. Together, the persistence of local autonomy and the accelerating economic and social changes brought unprecedented challenges until finally, in 1644, the Ming dynasty collapsed.

ADMINISTRATIVE AND ECONOMIC PROBLEMS How did a dynasty that, in the early seventeenth century, governed the world’s most economically advanced society (and perhaps a third of the world’s population) fall from power? As in the Ottoman Empire, responsibility often lay with the rulers and their inadequate response to economic and environmental change. Zhu Yijun, the Wanli Emperor (r. 1572–1620), secluded himself despite being surrounded by a staff of 20,000 eunuchs and 3,000 women. The “Son of Heaven” rarely ventured outside the palace compound, and when he moved within it a large retinue accompanied him, led by eunuchs clearing his path with whips. Ming emperors like Wanli quickly discovered that despite the elaborate arrangements and ritual performances affirming their position as the Son of Heaven, they had little control over the vast bureaucracy. An emperor frustrated with his officials could do little more than punish them or refuse to cooperate.

The timing of administrative breakdown in the Ming government was unfortunate, because expanding opportunities for trade led many individuals to circumvent official rules. From the mid-sixteenth century, bands of pirates ravaged the Chinese coast. The Ming government had difficulties regulating trade with Japan and labeled all pirates as Japanese, but many of the marauders were in fact Chinese who flouted imperial authority. In tough times, the roving gangs terrorized sea-lanes and harbors. In better times, some functioned like mercantile groups: their leaders mingled with elites, foreign trade representatives, and imperial officials. What made these predators so resilient—and their business so lucrative—was their ability to move among the mosaic of East Asian cultures.

As in the Islamic empires, while the influx of silver first stimulated the Chinese economy, it led to severe economic and, eventually, political problems. As we saw in Chapter 12, Europeans used New World silver to pay for their purchases of Chinese goods. As a result, by the early seventeenth century China imported more than twenty times more silver bullion (uncoined gold or silver) than it produced. As silver currency became the primary medium of exchange, market activity and state revenues both increased. When silver shipments to China declined, however, due to downturns in New World mining output and expensive European wars, the supply of money in China contracted; inflation suddenly gave way to deflation and shortages. Chinese peasants could not meet their obligations to state officials and merchants, and they took up arms in rebellion.

More information

A ceremonial silver helmet of the Qing dynasty. It has gold sections along the bottom and top of the helmet connected by a thin strip along the side. It is shaped like the top section of a tear drop with a flat top.

THE COLLAPSE OF MING AUTHORITY By the seventeenth century, the Ming’s administrative and economic difficulties were affecting their subjects’ daily lives. This was particularly evident when the regime failed to cope with devastation caused by natural disasters and climate change. As the price of grain soared in the northwestern province of Shanxi in the bad harvests of 1627–1628, the poor and the hungry fanned out to find food by whatever means they could muster. To deal with the crisis, the government imposed heavier taxes and cut the military budget. Bands of dispossessed Chinese peasants and mutinous soldiers then vented their anger at local tax collectors and officials.

The cycle of rebellion and weakened central authority that played out in so many other places took its predictable toll. Outlaw armies grew large under charismatic leaders. The most famous rebel leader, the “dashing prince” Li Zicheng, arrived at the outskirts of Beijing in 1644. Only a few companies of soldiers and a few thousand eunuchs were there to defend the capital’s 21 miles of walls, so Li Zicheng seized Beijing easily. Two days later, the emperor hanged himself. On the following day, the triumphant “dashing prince” rode into the capital and claimed the throne.

News of the fall of the Ming capital sent shock waves around the empire and beyond. In the far northeast, where China meets Manchuria, the army’s commander received the news within a matter of days. His task in the area was to defend the Ming against their menacing neighbor, a group that had begun to identify itself as Manchu. Immediately the commander’s position became precarious. Caught between an advancing rebel army on one side and the Manchus on the other, he made a fateful decision: he struck a pact with the Manchus for their cooperation to fight Li Zicheng, promising his new allies that “gold and treasure” awaited them in the capital. The Manchus joined Ming forces to defeat the rebels. After years of coveting the riches of the south, the Manchus were finally on their way to Beijing and, within months, had installed their own empire. (See Map 13.5.)

THE QING DYNASTY ASSERTS CONTROL Despite their small numbers, the Manchus overcame early resistance to their rule and oversaw an impressive expansion of their realm. The Manchus—the name was first used in 1635—were descendants of a Turkic-speaking group known as the Jurchens. They emerged as a force early in the seventeenth century, when their leader claimed the title of khan after securing the allegiance of various Mongol groups in northeastern Asia, paving the way for their eventual conquest of China. By that time, a rising Manchu population, based in Inner China and unable to feed their people in Manchuria, threatened to breach the Great Wall in search of better lands. The Manchus found a Chinese government in disarray from famines, civil war, and fiscal crisis, with central authorities overwhelmed by roving bands of peasant rebels.

More information

Map 13.5 is titled, From Ming to Qing China, 1644-1760.The map shows the area under Ming, the Manchu homeland, Manchu expansion before 1644, from 1644-1660, and additional area under Manchu dynasty, 1760, as well as tributary states and the location of the Great Wall. The Manchu homeland is a small area in Manchuria just north of Korea. Before 1644, they had expanded into all of Manchuria and Inner Mongolia. By 1660, expansion had taken over much of present-day eastern China (which also is the area under Ming). By 1760, the Manchu dynasty had taken over Outer Mongolia, Zungharia, East Turkestan, and Tibet. The Manchu tributary states include Nepal, Burma, Siam, Laos, Annam (Vietnam), Tongking, and Korea. The Great Wall lies on the border between Inner Mongolia and the area of Manchu expansion from 1644 to 1660.

MAP 13.5 | From Ming to Qing China, 1644–1760

Qing China under the Manchus expanded its territory significantly during this period. Find the Manchu homeland and then the area of Manchu expansion after 1644, when the Manchus established the Qing dynasty.

- Where did the Qing dynasty expand? Explain what this tells us about the priorities of the ruling elite, in particular with respect to global commerce.

- Explain the significance of the chronology of Chinese expansion. Does this qualify your answer to the first question?

- What does the chronology of Chinese expansion tell us about the evolution of the ruling elite’s priorities?

- Consider the scope of Chinese territorial expansion in this period, and, based on your reading, explain the challenges this posed for central authorities.

When the Manchus defeated Li Zicheng and seized power in Beijing in 1644, they numbered around 1 million. Assuming control of a domain that included perhaps 250 million people, they were keenly aware of their minority status. Taking power was one thing; keeping it was another. But keep it they did. In fact, during the eighteenth century the Manchu Qing (“pure”) dynasty (1644–1911) incorporated new territories, experienced substantial population growth, and sustained significant economic growth.

The key to China’s relatively stable economic and geographic expansion lay in its rulers’ shrewd and flexible policies. The early Manchu emperors were able and diligent administrators. They also knew that to govern a diverse population, they had to adapt to local ways. At the same time, Qing rulers were determined to convey a clear sense of their own majesty and legitimacy. Rulers relentlessly promoted patriarchal values. Widows who remained “chaste” enjoyed public praise, and women in general were urged to lead a “virtuous” life serving male kin and family. To the majority Han population, the Manchu emperor represented himself as the worthy upholder of familial values and classical Chinese civilization. The Manchus also emphasized their authority, their distinctiveness, and the submission of their mostly Han Chinese subjects. For example, Qing officials composed or translated important documents into Manchu and banned intermarriage between Manchu and Han, although this proved difficult to enforce.

Manchu impositions fell mostly on the peasantry, for the Qing financed their administrative structure through taxes on peasant households. In response, the peasants sought new lands to cultivate in border areas, often planting New World crops that grew well in difficult soils. This move introduced an important change in Chinese diets: while rice remained the staple of the wealthy, peasants increasingly subsisted on corn and sweet potatoes.

The Qing dynasty in China forged tributary relations with Korea, Vietnam, Burma, and Nepal, and its territorial expansion reached far into central Asia. In particular, the Manchus wanted to stabilize their frontiers and check any threat from an expanding Russia. Having brought domestic peace, the Qing accepted, for the first time, the need for diplomacy with expanding overland neighbors. Thanks to Jesuit intermediaries, Russian and Qing envoys negotiated China’s first treaty with Russia, the Treaty of Nerchinsk, in 1689. By recognizing sovereignty and borders, the pioneering treaty served both the Russian and Chinese empires internally and allowed each to put the squeeze on borderlanders and curb their autonomy.

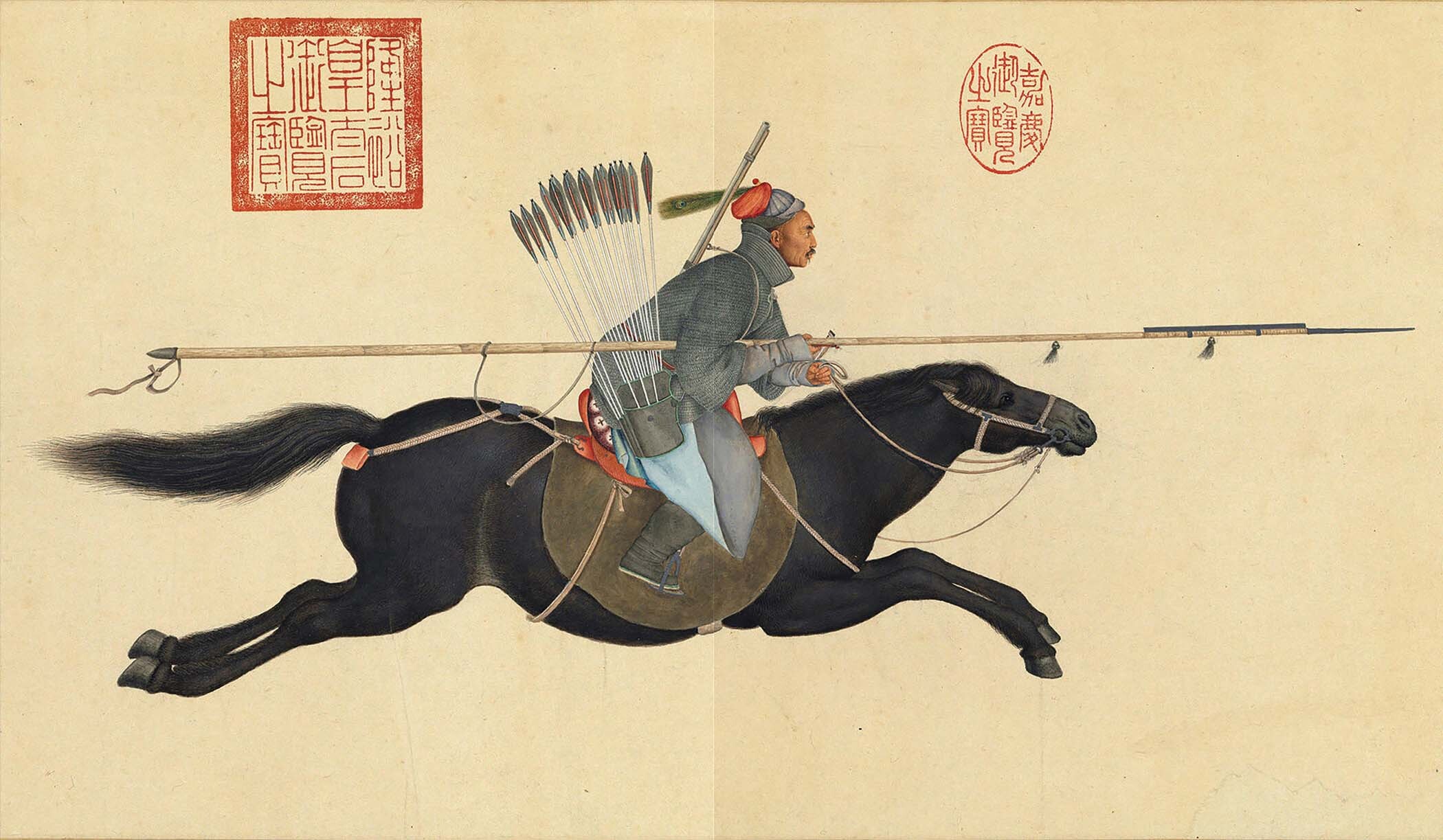

The treaty gave the Qing the room to crush one group of borderlanders in particular, the Junghars of western Mongolia. Many Junghars had converted to Buddhism from Islam in the seventeenth century and controlled much of central Asia. Clear of any Junghar-Russian alliance, the Qing launched brutal campaigns against the Junghar leader, Eredeniin Galdan. Galdan had studied Buddhist texts with the Dalai Lama in Tibet before subduing other khanate rivals—and then squaring up against the scale and might of Beijing. The conflict took decades, with the Qing’s military supply lines stretching across western China, and their armies roaming from Mongolia to Tibet. But in the long run, the Junghars could not escape the pressure and the loss of their pastures for their livestock, and they could not match the scale of the resources the Chinese state was prepared to throw at its frontier. Nor could they overcome internal divides among the Mongolian peoples. Hungry and deserted, Galdan finally took his own life in 1697. The Junghars finally fell in the mid-eighteenth century. The steppe lands from Mongolia to Tibet became a province of China called Xinjiang, a massive buffer zone between China and other land powers, and the victory made Beijing the ruler of Muslim and Buddhist peoples of the west.

More information

An illustration of the armored warrior Ayuxi on horseback. He holds a spear under his arm and has a quiver of arrows at his side and a bow across his back. There are Chinese characters at the top of the illustration.

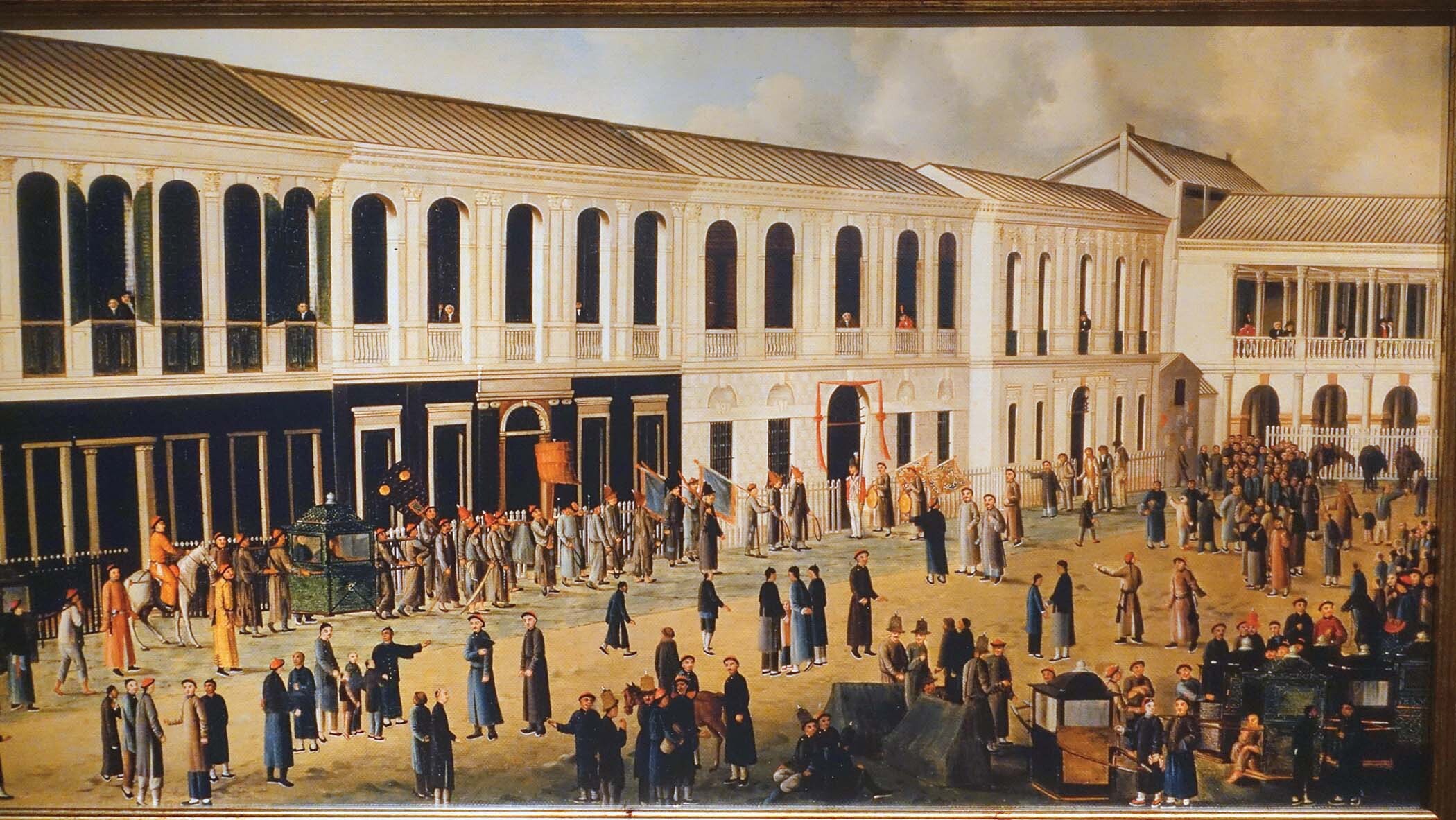

While officials redoubled their reliance on an agrarian base, trade and commerce flourished. Chinese merchants continued to ply the waters stretching from Southeast Asia to Japan, exchanging textiles, ceramics, and medicine for spices and rice. Although the Qing state vacillated about permitting maritime trade with foreigners in its early years, it sought to regulate external commerce more formally as it consolidated its rule. In 1720, in Canton, a group of merchants formed a monopolistic guild to trade with Europeans seeking coveted Chinese goods and peddling their own wares. Although the guild disbanded in the face of opposition from other merchants, it revived after the Qing restricted European trade to Canton. The Canton system, officially established by imperial decree in 1759, required European traders to have guild merchants act as guarantors for their good behavior and payment of fees.

Though the Qing disrupted some old Ming ways, there was a great deal of continuity, just as there was in the Ottoman Empire. The peasantry continued to practice popular faiths, cultivate crops, and stay close to fields and villages. Trade with the outside world was marginal and restricted to the coast. Like the Ming, the Qing cared more about the interior agrarian base than the commercial health of the empire, believing the former to be the foundation of prosperity and tranquility. As long as China’s peasantry could keep the dynasty’s coffers full, the government was content to squeeze the merchants when it needed funds. Some historians view this practice as a failure to adapt to a changing world order, as it ultimately left China vulnerable to outsiders—especially Europeans. But this became only clear in hindsight, after the mid-nineteenth century. Until then, Europe needed China more than the other way around. For the majority of Chinese people, no superior model of belief, politics, or economics was conceivable. Indeed, although the Qing had taken over a fractured dynasty in 1644, a century later China was enjoying a new level of prosperity.

More information

A painting of the foreign factories in Canto on a busy street. The factories are two stories and have arched windows on the second story. Many people walk on the street in front.

Tokugawa Japan

Integration with the Asian trading system exposed Japan to new external pressures, even as the islands grappled with internal turmoil. But the Japanese dealt with these pressures more successfully than the mainland Asian empires (Ottoman, Safavid, Mughal, and Ming), which saw political fragmentation and even the overthrow of ruling dynasties. In Japan, a single ruling family emerged. This dynastic state, the Tokugawa shogunate, accomplished something that most of the world’s other regimes did not: it regulated foreign intrusion. While Japan played a modest role in the expanding global trade, it remained free of outside exploitation.

UNIFICATION OF JAPAN During the sixteenth century, Japan had suffered from political instability as banditry and civil strife disrupted the countryside. Regional ruling families, called daimyos, had commanded private armies of warriors known as samurai. The daimyos sometimes brought order to their domains, but no one family could establish preeminence over the others. Although Japan had an emperor, his authority did not extend beyond the court in Kyoto.

Following an effort by military leaders to unify Japan, one of the daimyos, Tokugawa Ieyasu, seized power. This was a decisive moment. In 1603, Ieyasu assumed the title of shogun (military ruler), retaining the emperor in name only while taking the reins of power himself. He also solved the problem of succession, declaring that rulership would be hereditary and that his family would be the ruling household. Administrative authority shifted from Kyoto to the site of Ieyasu’s domain headquarters: the castle town called Edo (later renamed Tokyo). (See Map 13.6.) By the time Ieyasu died, Edo had become a major urban center with a population of 150,000. This hereditary Tokugawa shogunate lasted until 1867.

The Tokugawa shoguns ensured a flow of resources from the working population to the rulers and from the provinces to the capital. Villages paid taxes to the daimyos, who transferred resources to the seat of shogunate authority. No longer engaged in constant warfare, the samurai became administrators. Peace brought prosperity. Agriculture thrived. Improved farming techniques and land reclamation projects enabled the country’s population to grow from 10 million in 1550 to 16 million in 1600 and 30 million in 1700.

FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND FOREIGNERS Internal peace and prosperity did not insulate Japan from external challenges. When Japanese rulers tackled foreign affairs, their most pressing concern was the intrusion of Christian missionaries and European traders. Initially, Japanese officials welcomed these foreigners out of an eagerness to acquire muskets, gunpowder, and other new technology. But once the ranks of Christian converts swelled, Japanese authorities realized that Christians were intolerant of other faiths, believed Christ to be superior to any authority, and fought among themselves. The government thus suppressed Christianity and drove European missionaries from the country.

Even more troublesome was the lure of trade with Europeans. The Tokugawa knew that trading at various Japanese ports would pull the commercial regions in various directions, away from the capital. When it became clear that European traders preferred the ports of Kyūshū (the southernmost island), the shogunate restricted Europeans to trading only in ports under Edo’s direct rule in Honshū. Then, Japanese authorities expelled all European competitors. Only the Protestant (and nonproselytizing) Dutch won permission to remain in Japan, confined to an island near Nagasaki. The Dutch were allowed to unload just one ship each year, under strict supervision by Japanese authorities.

These measures did not close Tokugawa Japan to the outside world, however. Trade with China and Korea flourished, and the shogun received missions from Korea and the Ryūkyū Islands. Edo also gathered information about the outside world from the resident Dutch and Chinese (who included monks, physicians, and painters). A few Japanese were permitted to learn Dutch and to study European technology, shipbuilding, and medicine (see Chapter 14). By limiting such encounters, the authorities ensured that foreigners would not threaten Japan’s security.

More information

A painting of the city of Edo shows a small part of the curved wooden bridge over a river. Few people are shown crossing the bridge sheltering under straw capes from rain. Several buildings, trees, and mountains line the shore. A mountainous volcano is in the background.

The arrival of New World silver provided at least an initial boost to the major Asian economies. The Mughal Empire achieved its greatest influence in the seventeenth century. Despite a change in the ruling dynasty, China remained the world’s center of wealth and power, although there, as elsewhere in Asia, silver caused inflation and altered relations between center and periphery. Ottoman domains shrank, and Europeans achieved important commercial footholds in parts of India and Southeast Asia.

More information

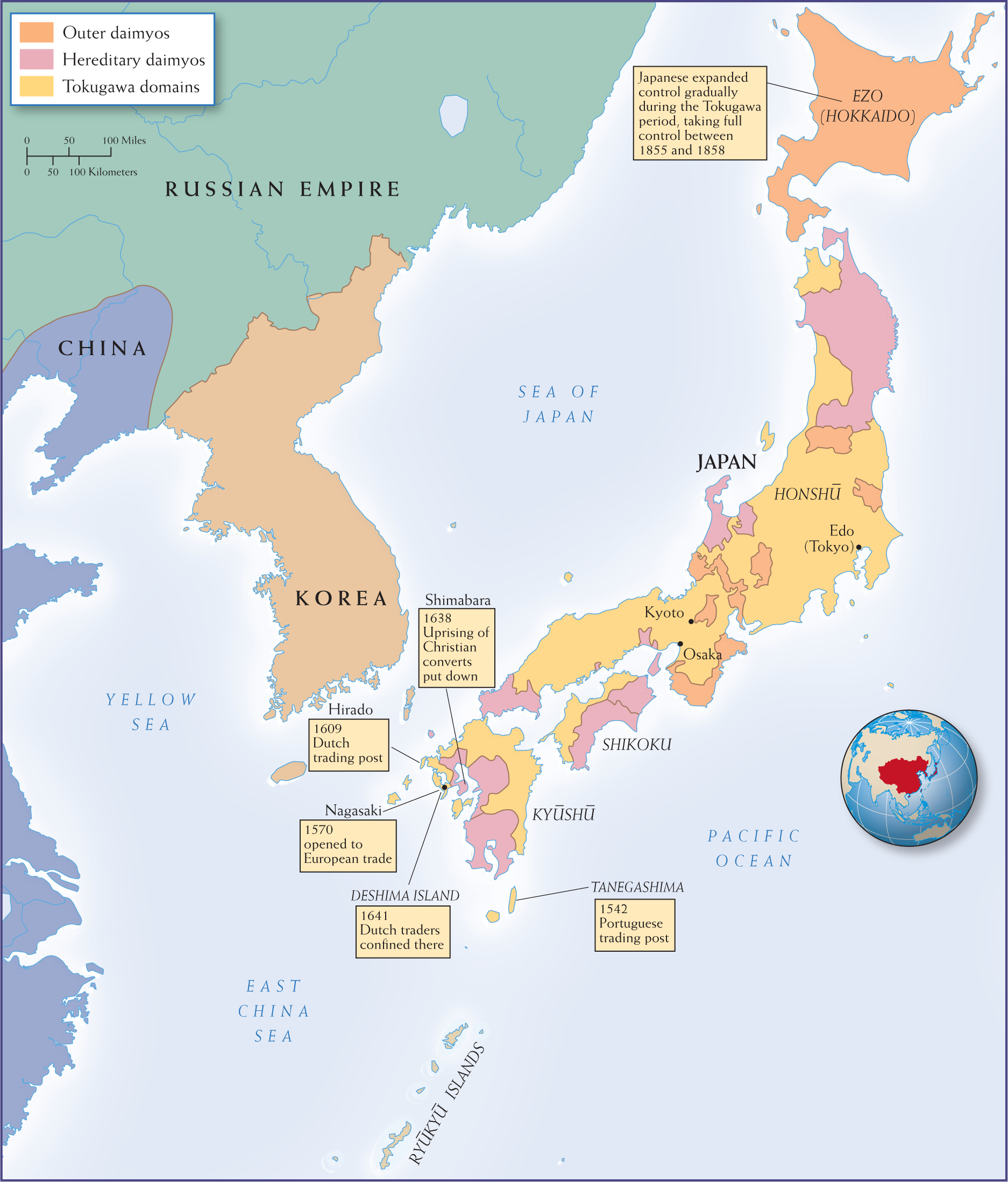

Map 13.6 is titled, Tokugawa Japan, 1603-1867. The map displays regions of hereditary daimyos, Tokugawa domains, and outer daimyos. Most of Japan is under Tokugawa domains. Hereditary daimyos control small pockets of land scattered across the country, particularly in Kyushu, Shikoku, and the northern part of Honshu. In the north, outer daimyos control the island of Ezo (Hokkaido). The map also shows that there was a Portuguese trading post on the island of Tanegashima in 1542. In 1570, Nagasaki opened to European trade. Dutch traders were confined to Deshima Island in 1641. There was a Dutch trading post in Hirado in 1609. An uprising of Christian converts was put down on Shimabara in 1638.

MAP 13.6 | Tokugawa Japan, 1603–1867

The Tokugawa shoguns created a strong central state in Japan at this time.

- According to this map, how extensive was their control?

- Based on your reading, what foreign states were interested in trade with Japan?

- How, according to the chapter, did Tokugawa leaders attempt to control relations with foreign states and other entities?

Glossary

- Mamluks

- (Arabic for “owned” or “possessed”) Military men who ruled Egypt as an independent regime from 1250 until the Ottoman conquest in 1517.

- Manchus

- Descendants of the Jurchens who helped the Ming army recapture Beijing in 1644 after its seizure by the outlaw Li Zicheng. The Manchus numbered around 1 million but controlled a domain that included perhaps 250 million people. Their rule lasted more than 250 years and became known as the Qing dynasty.

- Qing dynasty

- (1644–1911) Minority Manchu rule over China that incorporated new territories, experienced substantial population growth, and sustained significant economic growth.

- Canton system

- System officially established by imperial decree in 1759 that required European traders to have Chinese guild merchants act as guarantors for their good behavior and payment of fees.

- Tokugawa shogunate

- Hereditary military administration founded in 1603 that ruled Japan while keeping the emperor as a figurehead; it was toppled in 1868 by reformers who felt that Japan should adopt, not reject, western influences.

- Qing dynasty

- (1644–1911) Minority Manchu rule over China that incorporated new territories, experienced substantial population growth, and sustained significant economic growth.