CORE OBJECTIVES

COMPARE the impact of trade and religion on state power in Europe and the Mughal Empire.

Transformations in Europe

Between 1600 and 1750, religious conflict and the consolidation of dynastic power, spurred on by long-distance trade and climate change, transformed Europe. Commercial centers shifted northward, and Spain and Portugal lost ground to England and France. To the east, the state of Muscovy expanded dramatically to become the sprawling Russian Empire.

Expansion and Dynastic Change in Russia

During this period the Russian Empire expanded to become one of the world’s largest-ever states. It gained positions on the Baltic Sea and the Pacific Ocean, and it established political borders with both the Qing Empire and Japan. These momentous shifts involved the elimination of steppe nomads as an independent force. Culturally, Europeans as well as Russians debated whether Russia belonged more to Europe or to Asia. The answer was both.

MUSCOVY BECOMES THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE The principality of Moscow, or Muscovy, like Japan and China, used territorial expansion and commercial networks to consolidate a powerful state. This was the Russian Empire, the name given to Muscovy by Tsar Peter the Great around 1700. (Tsar was a Russian word derived from the Latin Caesar to refer to the Russian ruler.) Originally a mixture of Slavs, Finnish tribes, Turkic speakers, and many others, Muscovy spanned parts of Europe, much of northern Asia, numerous North Pacific islands, and even—for a time—a corner of North America (Alaska).

Like most empires, Russia emerged out of turmoil. Security concerns inspired the Muscovite regime to seize territory in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Because the steppe, which stretches deep into Asia, remained a highway for nomadic peoples (especially descendants of the Mongols), Muscovy sought to dominate the areas south and east of Moscow. Beginning in the 1590s, Russian authorities built forts and trading posts along Siberian rivers, and by 1639 the state’s borders reached the Pacific. Thus, in just over a century Muscovy had claimed an empire straddling Eurasia and incorporated peoples of many languages and religions. (See Map 13.7.)

More information

Map 13.7 is titled, Russian Expansion, 1462-1795. The map displays regions of Muscovy in 1462, expansions of Russia from 1462-1598, 1598-1689, and 1689-1795, as well as area occupied by Russia from 1644 to 1689, and the Qing Empire in 1760. In 1462, the state of Muscovy was a small area around and east of Moscow. By 1598, Russia has expanded past the Ural Mountains south and east almost to Omsk, as well as west to Smolensk and north past Archangel to the Barents Sea. Russia has expanded into all of Siberia by 1689. By 1795, Russia has expanded west to the Polish border, south to Ukraine and Crimea, and further east to Kamchatka. Russia occupies an area north of the Amur River from 1644-1689. The Qing empire covers Manchuria, Mongolia, and those areas further south that are part of present-day China.

MAP 13.7 | Russian Expansion, 1462–1795

The state of Muscovy incorporated vast territories through overland expansion as it grew and became the Russian Empire.

- Using the map key, identify the different expansions the Russian Empire underwent between 1462 and 1795 and the directions it generally expanded in.

- With what countries and cultures did the Russian Empire come into contact?

- According to the text, what drove such dramatic expansion?

Much of this expansion occurred despite the dynastic chaos that followed the death of Tsar Ivan IV in 1584. Ultimately, a group of prominent families reestablished central authority and threw their weight behind a new family of rulers in 1613. These were the Romanovs, court barons who set about reviving the Kremlin’s fortunes. (The Kremlin was a medieval walled fortress where the Muscovite grand princes—later, tsars—resided.) Like the Ottoman and Qing leaders, Romanov tsars and their aristocratic supporters would retain power into the twentieth century.

ABSOLUTIST GOVERNMENT AND SERFDOM In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Romanovs created an absolutist system of government. Only the tsar had the right to make war, tax, judge, and coin money. The Romanovs also made the nobles serve as state officials. Now Russia became a despotic state that had no political assemblies for nobles or other groups, other than mere consultative bodies like the imperial senate. Indeed, away from Moscow, local aristocrats enjoyed nearly unlimited authority in exchange for loyalty and tribute to the tsar.

During this period, Russia’s peasantry bore the burden of maintaining the wealth of the nobility and the monarchy. Most peasant families gathered into communes, isolated rural worlds where people helped one another deal with the harsh climate, severe landlords, and occasional poor harvests. Communes functioned like extended kin networks in which members supported one another. In 1649, peasants were legally bound as serfs to the nobles and the tsar, meaning that, in principle, they had to perform obligatory services and deliver part of their produce to their lords.

IMPERIAL EXPANSION AND MIGRATION A series of military victories in the eighteenth century made it possible to consolidate the empire and sparked significant population movements. The conquest of Siberia brought vast territory and riches in furs. Victory in a prolonged war with Sweden and then the incorporation of the fertile southern steppes, known as Ukraine, proved decisive. Peter the Great (r. 1682–1725) pushed for territorial expansion and modernized the Russian state. He founded a new capital at St. Petersburg, revamped agrarian taxes, adopted military reforms to create a more modern army, equipped with artillery and trained for war against other empires. This allowed Peter’s successors, including the hard-nosed Catherine the Great, to add even more territory. Catherine carved up the medieval state of Poland and annexed Ukraine, the grain-growing breadbasket of eastern Europe. By the late eighteenth century, Russia’s grasp extended from the Baltic Sea through the heart of Europe, Ukraine, and Crimea on the Black Sea, into the ancient lands of Armenia and Georgia in the Caucasus Mountains.

Expansion brought this new empire into contact and conflict with the older Ottoman (to the south) and Chinese (to the east) empires. Many people migrated eastward to Siberia. Some were fleeing serfdom; others were being deported for rejecting religious reforms. Battling astoundingly harsh temperatures (falling to –40 degrees Celsius/Fahrenheit) and frigid Arctic winds, these individuals traveled on horseback and trudged on foot to resettle in the east. But the difficulties of clearing forested lands or planting crops in boggy Siberian soils, combined with extraordinarily harsh winters, meant that many settlers died or tried to return. Isolation was a problem, too. There was no established land route back to Moscow until the 1770s, when exiles completed the Great Siberian Post Road through the swamps and peat bogs of western Siberia. The writer Anton Chekhov later called it “the longest and ugliest road in the whole world.”

By the end of the seventeenth century, giant land empires dominated Eurasia—often at the expense of borderland nomadic communities. From that point onwards those empires turned increasingly from warring against borderlanders to fighting each other over the balance of power in Eurasia.

Economic and Political Fluctuations in Central and Western Europe

During this period, western Europe was a study of contrasts. Its economies adapted to climate change and colonialism with ingenuity and innovation. But religious and political conflict spiraled out of control in bitter, brutal wars. The result was the birth of modern capitalism, powered by contending middle-scaled imperial regimes—bigger than the city-states of the Renaissance but puny next to the lumbering agrarian and territorial powerhouses of Asia and now Russia. It was this delicate balance of carnage and competition that set Europe apart. It also explains Europe’s outward aggression; once the cycle of war, fueled by the effects of climate change, crested in the middle of the seventeenth century, European rivals set aside their feuding within Europe and turned their eyes, their companies, and their gunships overseas.

Would this tilt have happened without the Little Ice Age? It’s impossible to say for sure. But what we do know is that freezing temperatures shortened agricultural growing seasons by one to two months. The result was escalating prices for essential grain products, famine, death, and widespread peasant unrest that fueled political discord. The cooling had a few benefits, however, including the magnificent violins, still prized today, crafted by Antonio Stradivari (1644–1737) from the denser wood that freezing temperatures produced.

THE THIRTY YEARS’ WAR For a century after Martin Luther broke with the Catholic Church (see Chapter 12), religious warfare raged in Europe. So did contests over territory, power, and trade. The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648)—a war between Protestant princes and the Catholic emperor for religious predominance in central Europe—reflected all of these. At its heart was a civil war within Hapsburg lands which sucked in Catholic and Protestant neighboring states.

The civil war between Protestants and Catholics within the Habsburg Empire soon became a war for preeminence in Europe. It took the lives of civilians as well as soldiers. In total, fighting, disease, and famine wiped out a third of the German states’ urban population and two-fifths of their rural population. Ultimately, the Treaty of Westphalia (1648) stated that as there was a rough balance of power between Protestant and Catholic states, they would simply have to put up with each other. But the war’s enormous costs provoked severe discontent in Spain, France, and England. Central Europe was so devastated that it did not recover in economic or demographic terms for more than a century.

The Thirty Years’ War transformed war making. Whereas most medieval struggles had been sieges between nobles leading small armies, centralized states fielding standing armies with artillery now waged decisive, grand-scale campaigns. The war also changed the ranks of soldiers: local enlisted men defending their king, country, and faith gave way to hired mercenaries or criminals doing forced service. Even officers, who had previously obtained their stripes by purchase or royal decree, now had to earn them. Gunpowder, cannons, and muskets became standardized. By the eighteenth century, Europe’s wars featured huge standing armies boasting a professional officer corps, deadly artillery, and long supply lines bringing food and ammunition to the front. The costs—material and human—of war began to soar.

More information

An illustration of numerous soldiers hanging from a tree while a large crowd of soldiers watches. Several people stand on a ladder propped against the tree. Several people watching hold flags and many hold spears. Several townspeople stand talking in the right side of the foreground.

WESTERN EUROPEAN ECONOMIES In spite of warfare’s human toll, it spurred European states’ commercial expansion. But not all European states grew equally. Warfare favored the rising powers, like the Netherlands, England (later, Britain), and France, at the expense of Spain and Portugal.

As European commercial dynamism shifted northward, the Dutch led the way with innovative commercial practices and a new mercantile elite. They specialized in shipping and in financing regional and long-distance trade. Their famous fluitschips carried heavy, bulky cargoes (like Baltic wood) with relatively small crews for Dutch merchants and other countries, too. Amsterdam’s merchants founded an exchange bank, established a rudimentary stock exchange, and pioneered systems of underwriting and insuring cargoes.

England and France also became commercial powerhouses, establishing aggressive policies to promote national business and drive out competitors. By stipulating that only English ships could carry goods between the mother country and its colonies, the English Navigation Act of 1651 protected English shippers and merchants—especially from the Dutch.

Economic development was not limited to port towns: the countryside, too, enjoyed breakthroughs in production. Most important was expansion in the production of food. In northwestern Europe, investments in water drainage, larger livestock herds, and improved cultivation practices generated much greater yields. Also, a four-field crop rotation involving wheat, clover, barley, and turnips kept nutrients in the soil and provided year-round fodder for livestock. As a result (and as we have seen many times before), increased agricultural output supported a growing urban population.

Production rose most where the organization of rural property changed. In England, in a movement known as enclosure, landowners took control of lands that traditionally had been common property serving local needs. Claiming exclusive rights to these lands, the landowners planted new crops or pastured sheep with the aim of selling the products in distant markets—especially cities. The largest landowners put their farms in the hands of tenants, who hired wage laborers to till, plant, and harvest. Thus, in England, peasant agriculture gave way to farms run by wealthy families who exploited the marketplace to buy what they needed (including labor) and to sell what they produced. In this regard, England led the way in a Europe-wide process of commercializing the countryside.

DYNASTIC MONARCHIES: FRANCE AND ENGLAND If Asian powers wrestled with the balance of centralizing versus decentralizing authority, so did European monarchs. In France, Louis XIII (r. 1610–1643) and especially his chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu, concentrated power in the hands of the king. Instead of sharing power with the aristocracy, much less commoners, the king and his counselors wanted to rule without constraints, to create an absolute monarchy. The ruler was not to be a tyrant, but his authority was to be complete and thorough, and his state free of bloody disorders. The king’s rule would be lawful, but he, not his jurists, would dictate the last legal word. If the king made a mistake, only God could call him to account. Thus, the Europeans believed in the “divine right of kings,” a political belief akin to that of imperial China, where the emperor was thought to rule with the mandate of heaven.

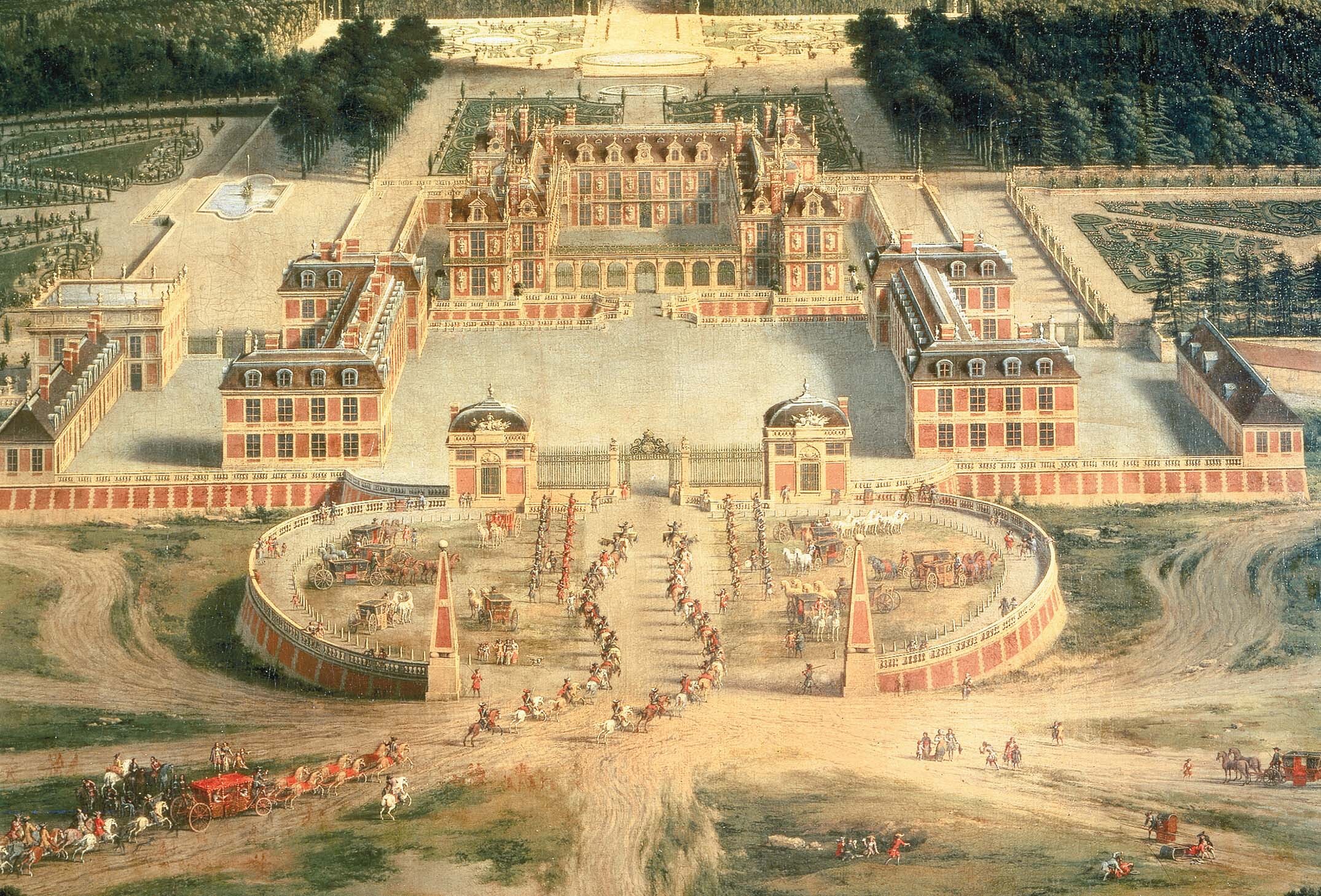

In absolutist France, privileges and state offices flowed from the king’s grace. All patronage networks ultimately linked to the king: these included financial supports the crown provided directly, as well as tax exemptions and a wide array of permissions—such as consent for a writer to publish a book or for people ranging from lawyers and professors to apothecaries, bookbinders, and butchers to work in a regulated trade. The great palace Louis XIV built at Versailles teemed with nobles from all over France seeking favor, dressing according to the king’s lavish (and expensive) fashion code, and attending the latest tragedies, comedies, and concerts.

In practice, the French absolutist government was not as absolute as the king and his ministers wished. Pockets of stalwart Protestants practiced their religion secretly, despite Louis XIV’s discriminatory measures against them. Peasant disturbances continued. Criticism of court life, wars, and religious policies filled anonymous pamphlets, jurists’ notebooks, and courtiers’ private journals. Members of the nobility also grumbled about their political misfortunes, but since the king had suppressed the traditional advisory bodies they had dominated, they had no formal way to express their concerns.

England might also have evolved into an absolutist regime, but there were important differences between England and France. In France, Catholic royals consolidated power; in England, by contrast, the feud between Catholics and Protestants plunged the country into civil war. Queen Elizabeth (r. 1558–1603) and her successors used many policies similar to those of the French monarchy, such as control of patronage and elaborate court festivities. Above all, the English Parliament remained an important force. Whereas the French kings did not consult the Estates-General to enact taxes, the English monarchs had to convene Parliament to raise money.

Under Elizabeth’s successors, fierce quarrels broke out over taxation, religion, and royal efforts to rule without parliamentary consent. Tensions ran high between Puritans (who preferred a simpler form of worship and more egalitarian church government) and Anglicans (who supported the state-sponsored, hierarchically organized Church of England headed by the king). Those tensions erupted in the 1640s into civil war that saw the victory of the largely Puritan parliamentary army and the beheading of the king, Charles I. Although the monarchy was restored a dozen years later, in 1660, the king’s relation to Parliament and the relationship between the crown and religion remained undecided (in particular, the right of Protestants to assume the throne).

More information

A painting of an aerial view of the Palace of Versailles. The huge estate sprawls over acres of land. The buildings surround several courtyards. To the sides and behind the palace there are several gardens and fountains. A procession enters through the front entrance.

Subsequent monarchs who aspired to absolute rule came into conflict with Parliament, whose members insisted on shared sovereignty and the right of Protestant succession. This dispute culminated in the Glorious Revolution of 1688–1689. In a bloodless upheaval, King James II fled to France and Parliament offered the crown to William of Orange and his wife, Mary (both Protestants). The outcome of the conflict established the principle that English monarchs must rule in conjunction with Parliament. Although the Church of England was reaffirmed as the official state church, Presbyterians and Jews were allowed to practice their religions. Catholic worship, still officially forbidden, was tolerated as long as the Catholics kept quiet. By 1700, then, England’s nobility and merchant classes had a guaranteed say in public affairs and assurance that state activity would privilege the propertied classes as well as the ruler. As a result, English rulers could borrow money much more effectively than their rivals could.

MERCANTILIST WARS The rise of new powers in Europe, especially France and England, intensified rivalries for control of Atlantic trade. As conflicts over colonies and sea-lanes replaced earlier religious and territorial struggles, commercial struggles became worldwide wars. Across the globe, European empires constantly skirmished over control of trade and territory. English and Dutch trading companies took aim at Portuguese outposts in Asia and the Americas, and then at each other. Ports in India suffered repeated assaults and counterassaults. In response, European powers built huge navies to protect their colonies and trade routes and to attack their rivals.

After 1715, a series of wars occurred mainly outside Europe, as empires feuded over colonial possessions. These conflicts were especially bitter in border areas, particularly in the Caribbean and North America. Each round of warfare ratcheted up the scale and cost of fighting.

The Seven Years’ War (known as the French and Indian War in North America) marked the culmination of this rivalry among European empires around the globe. Fought from 1756 to 1763, it saw Indigenous peoples, enslaved Africans, Bengali princes, Filipino militiamen, and European foot soldiers dragged into a contest over imperial possessions and control of the seas. The battles in Europe were relatively indecisive (despite being large), except in the hinterlands. After all, what sparked the war was a skirmish of British colonial troops (featuring a lieutenant colonel named George Washington) allied with Seneca warriors against French soldiers in the Ohio Valley. (See Map 13.2 for North American references.) In India, the war had a decisive outcome, for here the East India Company trader Robert Clive rallied 850 European officers and 2,100 Indian recruits to defeat the French (there were but 40 French artillerymen) and their 50,000 Maratha allies—men from an independent Indian empire in northern India—at Plassey. The British seized the upper hand, over everyone. Not only did the British drive off the French from the rich Bengali interior, but they also crippled Indian rulers’ resistance against European intruders. (See Map 12.4 for India references.)

The Seven Years’ War changed the balance of power around the world. Britain emerged as the foremost colonial empire. Its rivals, especially France and Spain, took a pounding; France lost its North American colonies, and Spain lost Florida (though it gained the Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi in a secret deal with France). In India, as well, the French were losers and had to acknowledge British supremacy in the wealthy provinces of Bihar and Bengal. But overwhelmingly, the biggest losers were Indigenous peoples everywhere. With the rise of one empire over all others, it was harder for Indigenous peoples to play the Europeans off against each other. Maratha princes faced the same problem. Clearly, as worlds became more entangled, the gaps between winners and losers grew more pronounced.

Glossary

- Muscovy

- The principality of Moscow. Originally a mixture of Slavs, Finnish tribes, Turkic speakers, and many others, Muscovy used territorial expansion and commercial networks to consolidate a powerful state and expanded to become the Russian Empire, a huge realm that spanned parts of Europe, much of northern Asia, numerous North Pacific islands, and even—for a time—a corner of North America (Alaska).

- Thirty Years’ War

- (1618–1648) Conflict begun between Protestants and Catholics in Germany that escalated into a general European war fought against the unity and power of the Holy Roman Empire.

- enclosure

- A movement in which landowners took control of lands that traditionally had been common property serving local needs.

- absolute monarchy

- Form of government in which one body, usually the monarch, controls the right to tax, judge, make war, and coin money. The term enlightened absolutist was often used to refer to state monarchies in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe.

- Seven Years’ War

- (1756–1763) Also known as the French and Indian War; worldwide war that ended when Prussia defeated Austria, establishing itself as a European power, and when Britain gained control of India and many of France’s colonies through the Treaty of Paris.