![]() Settlement, The First Cities

Settlement, The First Cities

SETTLEMENT, PASTORALISM, AND TRADE

Over many millennia, people had developed strategies to make the best of their environments. As populations expanded and sought out locations capable of supporting larger numbers, often it was reliable water sources that determined where and how people settled. Village dwellers gravitated toward predictable water supplies that enabled them to sow crops adequate to feed large populations. The story of the emergence of urban society is complex. In addition to having adequate water and a stable food supply, cities arose as a result of fundamental changes in economy, social organization, and political structures that required large, complex communities to function. Among these developments were conflict and warfare, causing people to coalesce around and submit to the authority of a leader, and populations large enough to require specialization of jobs and skills beyond the basic production of food.

While abundant rainfall was involved in the emergence of the world’s first villages, the breakthroughs into big cities occurred in drier zones where large rivers formed beds of rich alluvial soils (created by deposits from rivers when in flood). With irrigation innovations, soils became arable. Equally important, a worldwide warming cycle caused growing seasons to expand. These environmental and technical shifts profoundly affected who lived where and how.

As rivers sliced through mountains, steppe lands (vast treeless grasslands), and deserts before reaching the sea, their waters carried topsoils and deposited them along their banks, creating large and highly fertile deltas. The combination of rich soils, water for irrigation, and availability of domesticated plants and animals made river basins (areas drained by a river, including all its tributaries) attractive for human habitation. Here, cultivators began to produce agricultural surpluses to feed the city dwellers.

Early Cities along River Basins

![]() The Earliest Civilizations

The Earliest Civilizations

The material and social advances of the early cities occurred in a remarkably short period—from 3500 to 2000 BCE—in three locations: the basin of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in central Southwest Asia; the northern parts of the Nile River flowing toward the Mediterranean Sea; and the Indus River basin in northwestern South Asia. About a millennium later, a similar process began along the Yellow River in North China and the Yangzi River valley, laying the foundations for several cultures that evolved into the Chinese civilization that has flourished unbroken until this day. (See Map 2.1.)

In these regions, humans farmed and fed themselves by relying on intensive irrigation agriculture. Gathering in cities inhabited by rulers, administrators, priests, and craftworkers, the city dwellers changed how they related to their methods of organizing communities by worshipping new gods in new ways and by obeying divinely inspired monarchs and elaborate bureaucracies. They also transformed what and how they worshipped, praying to zoomorphic and anthropomorphic gods (taking the form and personality of animals and humans) who communicated through kings and priests living in palace complexes and temples. New technologies also appeared, ranging from the wheel for pottery production to metal and stoneworking for the creation of both luxury objects and utilitarian tools.

With cities came greater division of labor. Dense urban settlements enabled people to specialize in making goods for the consumption of others: weavers made textiles, potters made ceramics, and jewelers made precious ornaments. Soon these goods found additional uses in trade with outlying areas. And as trade expanded over longer distances, raw materials such as wood, metal, timber, and precious stones arrived in the cities. One of the most coveted metals was copper; easily smelted and shaped (not to mention shiny and alluring), it became the metal of choice for charms, sculptures, and valued commodities. When combined with arsenic or tin, copper hardens and becomes bronze, which was useful for tools and weapons. Consequently, this period marks the beginning of the Bronze Age, even though the use of this alloy extended into and flourished during the second millennium BCE (see Chapter 3).

As people congregated in cities, new technologies appeared. The wheel, for example, served both as a tool for mass-producing pottery and as a key component of vehicles used for transportation. At first vehicles were heavy, using two or four solid wooden wheels drawn by oxen or onagers (Asian wild asses). Two other technologies, metallurgy and stoneworking, both developed in the surrounding highlands near the raw materials and provided luxury objects and utilitarian tools.

As the dynamic urban enclaves evolved, they made intellectual advances. One significant advance was the invention of writing systems, which enabled people to record and transmit sounds and words through visual signs. An unprecedented cultural breakthrough, the technology of writing used the symbolic storage of words and meanings to extend human communication and memory: scribes figured out ways to record oral compositions as written texts and, eventually, epics recounting life in these river settlements.

The emergence of cities and city-states had crucial drawbacks for people who had been hunters and gatherers and/or had lived in towns. The rise of rulers, scribes, bureaucrats, priests, artisans, and wealthy farmers led to inequalities of wealth and power, a distinctive social stratification that erased the widespread egalitarianism that had characterized earlier communities. Men made gains at the expense of women, for the men dominated the prestigious positions, and societies became highly patriarchal. Moreover, people living close to cities either had to fashion their own city-states to protect themselves from their neighbors or find themselves exploited, or even enslaved.

The emergence of cities as population centers created one of history’s most durable worldwide distinctions: the urban-rural divide. Where cities appeared, at first alongside rivers, people adopted lifestyles based on specialized labor and the mass production of goods. In contrast, most people continued to cultivate the land or tend livestock, though they exchanged their grains and animal products for goods from the urban centers. The two ways of life were interdependent, and both worlds remained linked through family ties, trade, politics, and religion. Therefore, the new distinction never implied isolation, because the two lifeways supported each other.

THE GLOBAL VIEW

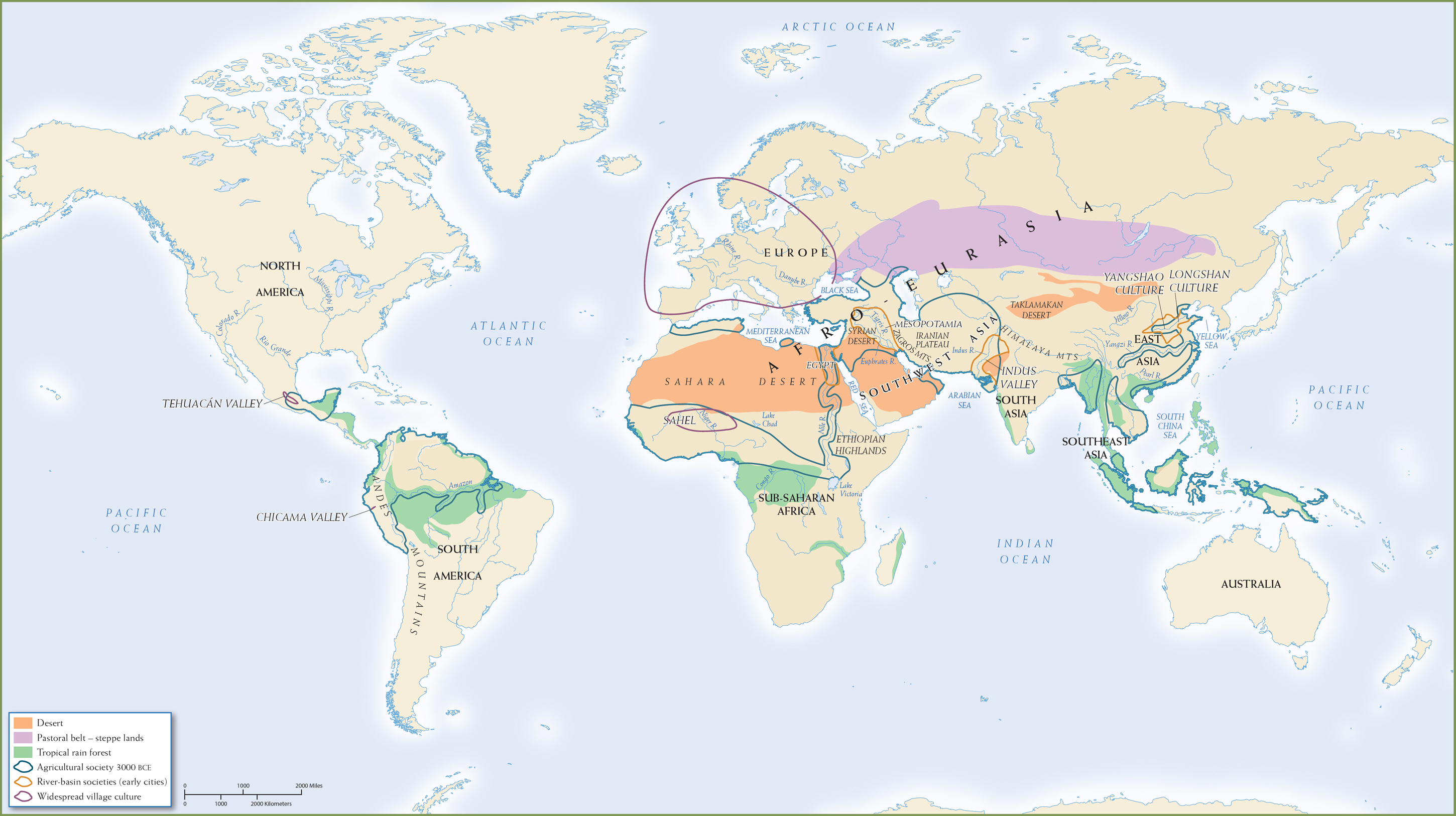

MAP 2.1 | The World in the Third Millennium BCE

Human societies became increasingly diversified as agricultural, urban, and pastoralist communities expanded. While urban communities began to develop in several major river basins in the Eastern Hemisphere, not every river basin produced cities in the third millennium BCE. Pastoralism, village life, agricultural communities, and continued hunting and gathering were by far the norm for most of the peoples of the earth.

- In what different regions did pastoralism and river-basin societies emerge? Where did pastoralism and river-basin societies not emerge? What might account for where these ways of life developed and where they did not?

- Considering the geographic features highlighted on this map, why do you think cities appeared in the regions that they did? What might explain why cities did not appear elsewhere?

- How did geographic and environmental factors promote interaction between pastoralist and sedentary agricultural societies?

Pastoralist Communities

The transhumant herder communities that had appeared in Southwest Asia around 5500 BCE (see Chapter 1) continued to be small and their settlements impermanent. They lacked substantial public buildings or infrastructure, but their seasonal moves were stable. Across the vast expanse of Afro-Eurasia’s great mountains and its desert barriers, and from its steppe lands ranging across inner and central Eurasia to the Pacific Ocean, these transhumant herders lived alongside settled agrarian people, especially when occupying their lowland pastures. They traded animal products such as meat, hides, and milk for grains, pottery, and tools produced in the agrarian communities.

In the arid environments of inner and central Eurasia, transhumant herding and agrarian communities initially followed the same combination of herding animals and cultivating crops that had proved so successful in Southwest Asia. However, it was in this steppe environment, unable to support large-scale farming, that some communities began to concentrate exclusively on animal breeding and herding. Though some continued to fish, hunt, and farm small plots in their winter pastures, by the middle of the second millennium BCE many societies had become full-scale pastoral communities.

These pastoralists dominated steppe life. The area that these pastoral societies occupied lay between 40 degrees and 55 degrees north and extended the entire length of Eurasia from the Great Hungarian Plain to Manchuria, a distance of 5,600 miles. The steppe itself divided into two zones, an eastern one and a western one, the separation point being the Altai Mountains in Central and East Asia where the modern states of Russia, China, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan come together. The region was “dominated by drought-resistant and frost-tolerant perennial herbaceous species, enlivened in the spring by flowers of the bulbous plants” (Cunliffe, By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean, p. 12). Over time, pastoralist groups—both transhumant herders and pastoral nomads (more on this distinction in Chapter 3)—played a vital role by interacting with cities, connecting more urbanized areas, and spreading ideas throughout Afro-Eurasia.

Increased Trade

When the earliest farming villages developed around 7000 BCE, trade patterns across Afro-Eurasia were already well established. Much of this trade was in exotic materials such as obsidian, a black volcanic glass that made superb chipped-stone tools. Although trade in nonessential items was small by the standards of later millennia, these trade goods provided vital links between different regions all across Afro-Eurasia.

Over thousands of years, trade increased. By the mid-third millennium BCE, flourishing communities populated the oases (fertile areas with water in the midst of arid regions) dotting the highlands of the Iranian plateau and the areas known today as northern Afghanistan and Turkmenistan. As these communities actively traded with their neighbors, trading stations at the borders facilitated exchanges among many partners. Here in these “borderlands,” urbanites exchanged cultural information. Their caravans of pack animals—first donkeys and wild asses; much later, camels—transported goods through deserts and steppes and across mountain barriers. Stopping at oasis communities to exchange their wares for supplies, these caravans also carried ideas across Afro-Eurasia. In this way, people of the borderlands—along with the cities they connected—have played a vital role in world history. (See Map 2.2.)

Glossary

- river basins

- Area drained by a river, including all its tributaries. River basins were rich in fertile soil, water for irrigation, and plant and animal life, which made them attractive for human habitation. Cultivators were able to produce surplus agriculture to support the first cities.

- bronze

- Alloy of copper and tin brought into Europe from Anatolia; used to make hard-edged weapons.

- urban-rural divide

- Division between those living in cities and those living in rural areas. One of history’s most durable worldwide distinctions, the urban-rural divide eventually encompassed the globe. Where cities arose, communities adopted lifestyles based on the mass production of goods and on specialized labor. Those living in the countryside remained close to nature, cultivating the land or tending livestock. They diversified their labor and exchanged their grains and animal products for necessities available in urban centers.