“THE GIFT OF THE NILE”: EGYPT

While Mesopotamia led the way in creating city-states, Egypt went a step further, unifying a 600-mile-long landmass under a single ruler. Here, complex societies grew on the banks of the Nile River, and by the third millennium BCE the Egyptian people had created a distinctive culture and a powerful, prosperous state. The earliest inhabitants along the banks of the Nile River were a mixed people. Some had migrated from the eastern and western deserts in Sinai and Libya as these areas grew barren from climate change. Others came from the Mediterranean. Equally important were peoples who trekked northward from Nubia and central Africa. Ancient Egypt was a melting pot where immigrants blended cultural practices and technologies.

Egypt had much in common with Mesopotamia. Like Mesopotamia, it had densely populated areas whose inhabitants depended on irrigation, gave their rulers immense authority, and created a complex social order. Like the Mesopotamians, the Egyptians built monumental architecture. Tapping the Nile waters gave rise to agrarian wealth, commercial and devotional centers, early states, and new techniques of communication. Egyptians gave their rulers immense authority and created a complex social order based in commercial and devotional centers. Yet the ancient Egyptian culture was profoundly distinct from its contemporaries in Mesopotamia. To understand its unique qualities, we must begin with geography. The environment and the natural boundaries of deserts, river rapids, and sea dominated the country and its inhabitants. Only about 3 percent of Egypt’s land area was cultivable, and almost all of that cultivable land was in the Nile Delta—the rich alluvial land lying between the river’s two main branches as it flows north of modern-day Cairo into the Mediterranean Sea. This environment shaped Egyptian society’s unique culture.

The Nile River and Its Floodwaters

Understanding Egypt requires appreciating the pulses of the Nile. The world’s longest river, it stretches 4,238 miles from its sources in the highlands of central Africa to its destination in the Mediterranean Sea. The Upper Nile is a sluggish river that cuts through the Sahara Desert. Rising out of central Africa and Ethiopia, its two main branches—the White and Blue Niles—meet at present-day Khartoum and then scour out a single riverbed 1,500 miles long to the Mediterranean. The annual floods gave the basin regular moisture and alluvial richness and gave rise to a society whose culture stretched along the navigable river and its carefully preserved banks. Away from the riverbanks, on both sides, lay a desert rich in raw materials but largely uninhabited. Egypt had no fertile hinterland like the sprawling plains of Mesopotamia. In a sense, Egypt was the most river focused of the river-basin cultures.

The Nile’s predictability as the source of life and abundance shaped the character of the people and their culture. In contrast to the wild and uncertain Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, the Nile was gentle and bountiful, leading Egyptians to view the world as beneficent. During the summer as the Nile swelled, local villagers built earthen walls that divided the floodplain into basins. By trapping the floodwaters, these basins captured the rich silt washing down from the Ethiopian highlands. Annual flooding meant that the land received a new layer of topsoil every year. The light, fertile soils made planting simple. Peasants cast seeds into the alluvial soil and then had their livestock trample them to the proper depth. The never-failing sun, which the Egyptians worshipped, ensured an abundant harvest. In the early spring, when the Nile’s waters were at their lowest and no crops were under cultivation, the sun dried out the soil.

The peculiarities of the relatively closed-off, one-river Nile region distinguished it from Mesopotamia, with its two rivers that acted as pump and drain to irrigate a flood plain that was relatively open on all sides. The Greek historian and geographer Herodotus 2,500 years ago noted that Egypt was the gift of the Nile and that the entire length of its basin was one of the world’s most self-contained geographical entities. Bounded on the north by the Mediterranean Sea, on the east and west by deserts, and on the south by cataracts (large waterfalls), Egypt was destined to achieve a common culture. The region was far less open to outsiders than Mesopotamia was.

Like the other pioneering societies, Egypt created a common culture by balancing regional tensions and reconciling regional rivalries. Ancient Egyptian history is a struggle of opposing forces: the north, or Lower Egypt, versus the south, or Upper Egypt; the sand, the so-called red part of the earth, versus the rich soil, described as black; life versus death; heaven versus earth; order versus disorder. For Egypt’s ruling groups—notably the kings—the primary task was to bring stability, or order, known as ma’at, out of these antagonistic impulses. The Egyptians believed that keeping chaos, personified by the desert and its marauders, at bay through attention to ma’at would allow all that was good and right to occur.

The Egyptian State and Dynasties

Once the early Egyptians harnessed the Nile to agriculture, the area changed from scarcely inhabited to socially complex. Whereas Mesopotamia to its northeast developed gradually, Egypt seemed to grow overnight. It quickly became a powerhouse state, projecting its splendor along the full length of the river valley.

|

TABLE 2.1 | Dynasties of Ancient Egypt |

|

|

DYNASTY* |

DATE |

|

Predynastic Period dynasties I and II |

3100–2686 BCE |

|

Old Kingdom dynasties III–VI |

2686–2181 BCE |

|

First Intermediate Period dynasties VII–X |

2181–2055 BCE |

|

Middle Kingdom dynasties XI–XIII |

2055–1650 BCE |

|

Second Intermediate Period dynasties XIV–XVII |

1650–1550 BCE |

|

New Kingdom dynasties XVIII–XX |

1550–1070 BCE |

|

Third Intermediate Period dynasties XXI–XXV |

1070–747 BCE |

|

Late Period dynasties XXVI–XXXI |

747–332 BCE |

|

Source: Compiled from Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson, eds., The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (London: British Museum Press, 1995), pp. 310–11. |

|

The king, later called the pharaoh, was at the center of Egyptian life (Egyptian kings did not use the title pharaoh until the mid to late second millennium BCE). The king’s primary responsibility was to ensure that the forces of nature, in particular the regular flooding of the Nile, continued without interruption. This task had more to do with appeasing the gods than with running a complex hydraulic system requiring considerable oversight. The king also had to protect his people from invaders from the eastern and western deserts as well as from Nubians on the southern borders and from the people of the sea on the north. These groups threatened Egypt with social chaos. As guarantors of the social and political order, the early kings depicted themselves as shepherds. In wall carvings, artists portrayed them carrying the crook and the flail, indicating their responsibility for the welfare of their flocks (the people) and of the land. Moreover, an elaborate bureaucracy organized labor and produced public works, sustaining both the king’s vast holdings and general order throughout the realm.

The narrative of ancient Egyptian history follows its thirty-one dynasties, spanning three millennia from 3100 BCE down to its conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. (See Table 2.1.) Since the nineteenth century, however, scholars have recast the story around three periods of dynastic achievement: the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, and the New Kingdom. At the end of each era, cultural flourishing suffered a breakdown in central authority, known, respectively, as the First, Second, and Third Intermediate Periods.

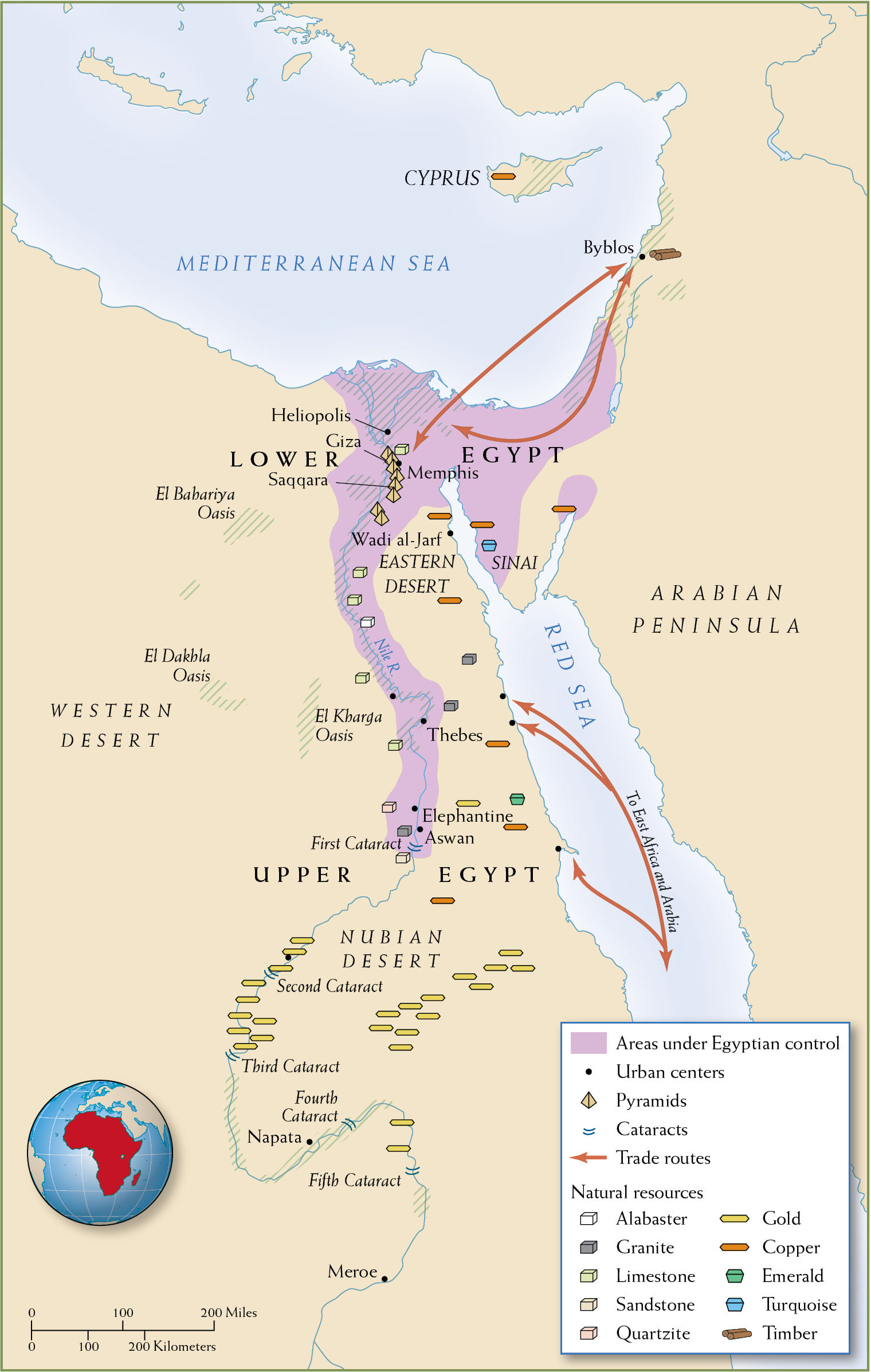

MAP 2.4 | Old Kingdom Egypt, 2686–2181 BCE

Old Kingdom Egyptian society reflected a strong influence from its geographical location.

- What geographical features contributed to Egypt’s isolation from the outside world and the people’s sense of their unity?

- What natural resources enabled the Egyptians to build the Great Pyramids? What resources enabled the Egyptians to fill those pyramids with treasures?

- Based on the map, why do you think it was important to the people and their rulers for Upper and Lower Egypt to be united?

Kings and Pyramids

The Third Dynasty (2686–2613 BCE) launched the foundational period known as the Old Kingdom, the golden age of ancient Egypt. (See Map 2.4.) By the time this dynasty came to power, the basic institutions of the Egyptian state were in place, including the centrality and superiority of the king, as well as the rituals, building projects, and ideologies that supported his power.

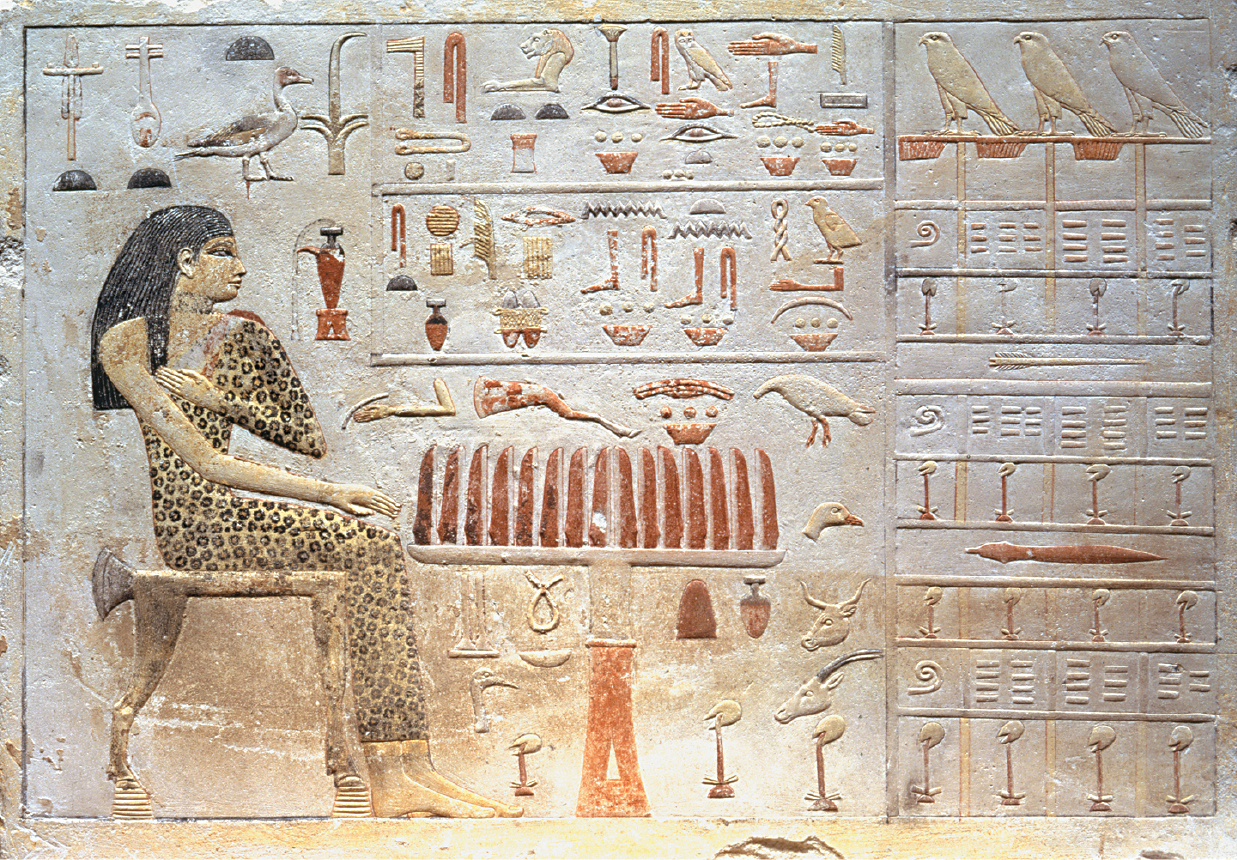

The king presented himself to the population by means of impressive architectural spaces, and the priestly class performed rituals reinforcing his supreme status within the universe’s natural order. One of the most important rituals was the Sed festival, which renewed the king’s vitality after he had ruled for thirty years. Although the festival focused on the king’s well-being, its origins lay in ensuring the perpetual presence of water. King Djoser, from the Third Dynasty, celebrated the Sed festival in his tomb complex at Saqqara. This magnificent complex includes the world’s oldest stone structure, dating to around 2650 BCE. Here Djoser’s architect, Imhotep, designed a step pyramid that rose 200 feet above the plain. It dominated the landscape, much like the later mud-brick palaces and ziggurats of Mesopotamian city-states would. Djoser’s mountain-like step pyramid stood at the center of an enormous walled precinct housing five courts, where the king performed rituals emphasizing the divinity of kingship and the unity of Upper and Lower Egypt. Pervasive at this pyramid were symbols stressing this unity, embodied in the entwined lotus and papyrus, representing each region. The step pyramid complex incorporated artistic and architectural forms that would characterize Egyptian culture for millennia.

Pyramid building evolved rapidly from the step version of Djoser to the grand pyramids of the Fourth Dynasty (2613–2494 BCE). These kings erected their magnificent structures at Giza, just outside modern-day Cairo and not far from the early royal cemetery site of Saqqara. The pyramid of Khufu, rising 481 feet aboveground, is the largest stone structure in the world, and its corners are almost perfectly aligned to due north, west, south, and east. Khafre’s pyramid, built by Khufu’s son, though smaller, retains some of its original limestone casing and enjoys the protective presence of the Sphinx.

Surrounding these royal tombs were those of high officials, almost all members of the royal family. The labor force that constructed the pyramids and tombs for the elite was made up of peasants and paid workers, who labored for the state at certain times of the year, as well as enslaved people captured and brought from Nubia and the Mediterranean. Filling these monuments with wealth for the occupants’ afterlife similarly required a range of specialized labor (from jewelers to weavers to stone carvers to furniture makers). Long-distance trade was required to bring from far away not only the jewels and precious metals (like lapis lazuli, carnelian, and silver) required for such offerings, but also the materials to construct the ships that helped make that trade possible (timber from Byblos). Through their majesty and complex construction, the Giza pyramids reflect the degree of centralization and the surpluses in Egyptian society at this time as well as the trade and specialized labor that fueled these undertakings.

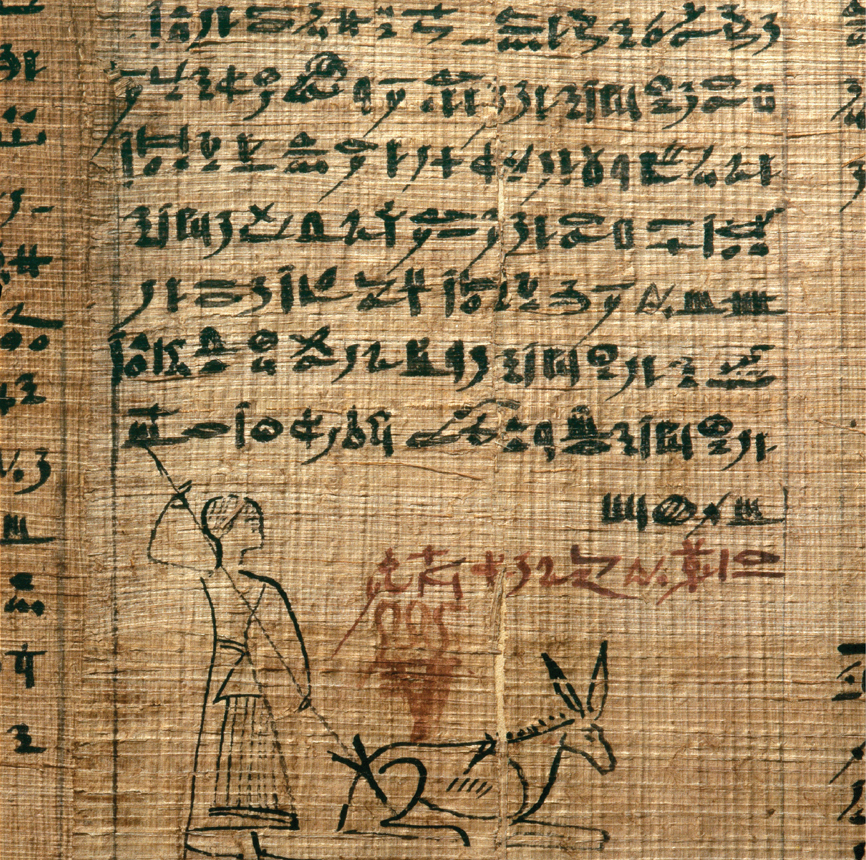

The Giza pyramids also underscore the remarkable feats that Egypt’s bureaucracy could accomplish. The oldest papyrus texts ever found—including a set of bureaucratic records kept by an official named Merer around 2550 BCE, excavated recently at the ancient port of Wadi al-Jarf—document a meticulous timetable for the gathering of stone for pyramid construction during Khufu’s reign and tabulations of food to feed workers. Construction of pyramids entailed the backbreaking work of quarrying the massive stones, digging a canal so barges could bring them from the Nile to the base of the Giza plateau, building a harbor there, and then constructing sturdy brick ramps that could withstand the stones’ weight as workers hauled them ever higher along the pyramids’ faces. Most likely a permanent workforce of up to 21,000 laborers endured 10-hour workdays, 300 days a year, for approximately 14 years just to complete the great pyramid of Khufu. The finished product was a miracle of engineering and planning. Khufu’s great pyramid contained 21,300 blocks of stone with an average weight of 2½ tons, though some stones weighed up to 16 tons. Roughly-speaking, one stone had to be put in place every 2 minutes during daylight. The stone blocks were planed so precisely that they required no mortar.

Gods, Priesthood, and Magical Power

Religion stood at the center of this ancient world, so all aspects of the culture reflected spiritual expression. Egyptians understood their world as inhabited by three groups: gods, kings, and the rest of humanity. Established at the time of creation, Egyptian cosmic order did not seek balance among people (for it buttressed the inequalities and stark hierarchies of Egyptian society); rather, Egyptian religion sought balance between universal order (ma’at) and disorder. It was the job of the king to maintain this cosmic order for eternity. After death, the king was destined to be a god. This divine destiny compelled him to behave like a god on earth: serene, orderly, merciful, and perfect. He always wore an expression of divine peace, not the angry snarl of mere human power.

CULTS OF THE GODS Official religious practices took place in the main temples, the heart of ceremonial events. The king and his agents cared for the gods in their temples, giving them respect, adoration, and thanks. In return the gods, embodied in sculptured images, maintained order and nurtured the king and—through him—all humanity. In this contractual relationship, the gods were passive and serene while the kings were active, a difference that reflected their unequal relationship. The practice of religious rituals and communication with the gods formed the cult, whose constant and correct performance was the foundation of Egyptian religion. Its goal was to preserve the cosmic order fundamental to creation and prosperity.

As in Mesopotamian city-states, every region in Egypt had its resident god. Some gods, such as Amun (believed to be physically present in Thebes, the political center of Upper Egypt), came to transcend regional status because of the importance of their hometown. Over the centuries, the Egyptian gods evolved, combining often contradictory aspects into single deities represented by symbols: animals and human figures that often had animal as well as divine attributes. They included Osiris, the god of regeneration and the underworld; Horus, the sky god of kingship; Hathor, the goddess of childbirth and love; Ra, the sun god; and Amun, a creator considered to be the hidden god.

One of the most enduring cults was that of the goddess Isis, who represented ideals of sisterhood and motherhood. According to Egyptian mythology, Isis, the wife of the murdered and dismembered Osiris, commanded her son, Horus, to reassemble all of the parts of Osiris so that he might reclaim his rightful place as king of Egypt, taken from him by his assassin, his evil brother Seth. Osiris was seen as the god of rebirth, while Isis was renowned for her medicinal skills and knowledge of magic. For millennia her principal place of worship was a magnificent temple on the island of Philae. Even as late as the fourth century CE, well after the Greeks and Romans had conquered Egypt at the end of the first millennium BCE, the people continued to pay homage to Isis at her Philae temple.

THE PRIESTHOOD Although the responsibility for upholding cults fell to the king, the actual tasks of upholding the cult—regulating rituals according to a cosmic calendar and mediating among gods, kings, and society—fell to one specialist class: the priesthood. Creating this class required elaborate rules for selecting and training the priests to project the organized power of spiritual authority. The fact that only the priests could enter the temple’s inner sanctum demonstrated their exalted status. The god, embodied in the cult statue, left the temple only at great festivals. Even then the divine image remained hidden in a portable shrine. This arrangement ensured that priests monopolized communication between spiritual powers and their subjects—and that Egyptians understood their own subservience to the priesthood.

Although the priesthood helped unify the Egyptians and focused their attention on the central role of temple life, unofficial religion was equally important. Ordinary ancient Egyptians matched their elite rulers in faithfulness to the gods, but their distance from temple life caused them to find different ways to fulfill their religious needs and duties. Thus, they visited local shrines, just as those of higher status visited the temples. There they prayed, made requests, and left offerings to the gods.

MAGICAL POWERS Unlike modern sensibilities that might see magic as opposed to, or different from, categories such as religion or medicine, Egyptians saw magic (personified by the god Heka) as a category closely intertwined with, if not indistinguishable from, the other two. Magic, or Heka, was a force that was present at creation and preexisted order and chaos. Magic had a special importance for commoners, who believed that amulets (ornaments worn to bring good fortune and to protect against evil forces) held extraordinary powers—for example, preventing illness and guaranteeing safe childbirth. To deal with profound questions, commoners looked to omens and divination (a practice that residents of Mesopotamia and ancient China also used to predict and control future events). Like the elites, commoners attributed supernatural powers to animals. Chosen animals received special treatment in life and after death: for example, the Egyptians adored cats, whom they kept as pets and whose image they used to represent certain deities. Apis bulls, sacred to the god Ptah, merited special cemeteries and mourning rituals. Ibises, dogs, jackals, baboons, lizards, fish, snakes, crocodiles, and other beasts associated with deities enjoyed similar privileges. Spiritual expression was central to Egyptian culture at all levels, and religion helped shape the society’s other cultural achievements, including the development of a written language.

Writing and Scribes

Egypt, like Mesopotamia, was a scribal culture. Egyptians often said that peasants toiled so that scribes could live in comfort; in other words, literacy sharpened the divisions between rural and urban worlds. Writing appeared in Egypt at roughly the same time as it did in Mesopotamia, sometime after 3500 BCE. By the middle of the third millennium BCE, literacy was well established among small circles of experts in Egypt and Mesopotamia. The fact that few individuals were literate heightened the scribes’ social status. Although in both cultures writing may have emerged in response to economic needs, people in Egypt soon grasped its utility for commemorative and religious purposes.

Ancient Egyptians used two forms of writing. Elaborate hieroglyphs (from the Greek “sacred carving”) served in formal temple, royal, or divine contexts. More common, however, was hieratic writing, a cursive script written with ink on papyrus or pottery. (Demotic writing, from the Greek demotika, meaning “popular” or “in common use,” developed much later and became the vital transitional key on the Rosetta Stone that ultimately allowed the nineteenth-century decipherment of hieroglyphs.) Used for record keeping, hieratic writing also found uses in letters and works of literature—including narrative fiction, manuals of instruction and philosophy, cult and religious hymns, love poems, medical and mathematical texts, collections of rituals, and mortuary books.

Literacy spread first among upper-class families. Most students started training when they were young. After mastering the copying of standard texts in hieratic cursive or hieroglyphs, students moved on to literary works. The upper classes prized literacy as proof of high intellectual achievement. When elites died, they had their student textbooks placed alongside their corpses as evidence of their talents. The literati produced texts mainly in temples, where these works were also preserved. Writing in hieroglyphs and the composition of texts in hieratic, and later demotic, script continued without break in ancient Egypt for almost 3,000 years.

The Prosperity and Demise of Old Kingdom Egypt

Cultural achievements, agrarian surpluses, and urbanization ultimately led to heightened standards of living and rising populations. Under pharaonic rule, Egypt enjoyed spectacular prosperity. Its population grew at an unprecedented rate, swelling from 350,000 in 4000 BCE to 1 million in 2500 BCE and nearly 5 million by 1500 BCE.

As the Old Kingdom expanded without a uniting or dominating city, like Sargon’s Akkad in late third-millennium BCE Mesopotamia, the Egyptian state became more dispersed and the dynasties began to look increasingly outward. Expansion and decentralization eventually exposed the dynasties’ weaknesses. The shakeup resulted not from external invasion or from bellicose rivalry between city-states (as in Mesopotamia), but from feuding among elite political factions. More important, an extended drought that occurred across Afro-Eurasia toward the end of the third millennium profoundly strained Egypt’s extensive irrigation system. As the Nile could no longer water the lands that fed the region’s million inhabitants, images of great suffering filled the royal tombs’ walls.

Royal power, along with the Old Kingdom, collapsed in the three years following the death of Pepy II in 2184 BCE. For the next hundred years, rivals jostled for the throne. Magnates, local people of influence, assumed hereditary control of the government in the provinces and treated lands previously controlled by the royal family as their personal property. And local leaders plunged into bloody regional struggles to keep the irrigation works functioning for their own communities. This so-called First Intermediate Period lasted roughly from 2181 to 2055 BCE, until the century-long drought ended. Although the Old Kingdom declined, it established institutions and beliefs that endured and were revived several centuries later.

Notes

- The term dynasty generally refers to a series of rulers who are related to one another. Intermediate periods mark breaks between the kingdoms (Old, Middle, and New). While scholars make attempts to synchronize the dates with modern chronology and other events in the ancient world, the succession of rulers comes from Egyptian texts. The term pharaoh, as a title for the Egyptian king, came into use in the New Kingdom. Return to reference *