THE INDUS RIVER VALLEY: A PARALLEL CULTURE

The Indus River valley, in South Asia, was yet another area in which large-scale cities emerged. Here they came to the fore later than in Mesopotamia and Egypt, in the mid third millennium BCE. The urban culture of the Indus area is called “Harappan” after the large site of Harappa that arose in the third millennium BCE on the banks of the Ravi River, a tributary of the Indus.

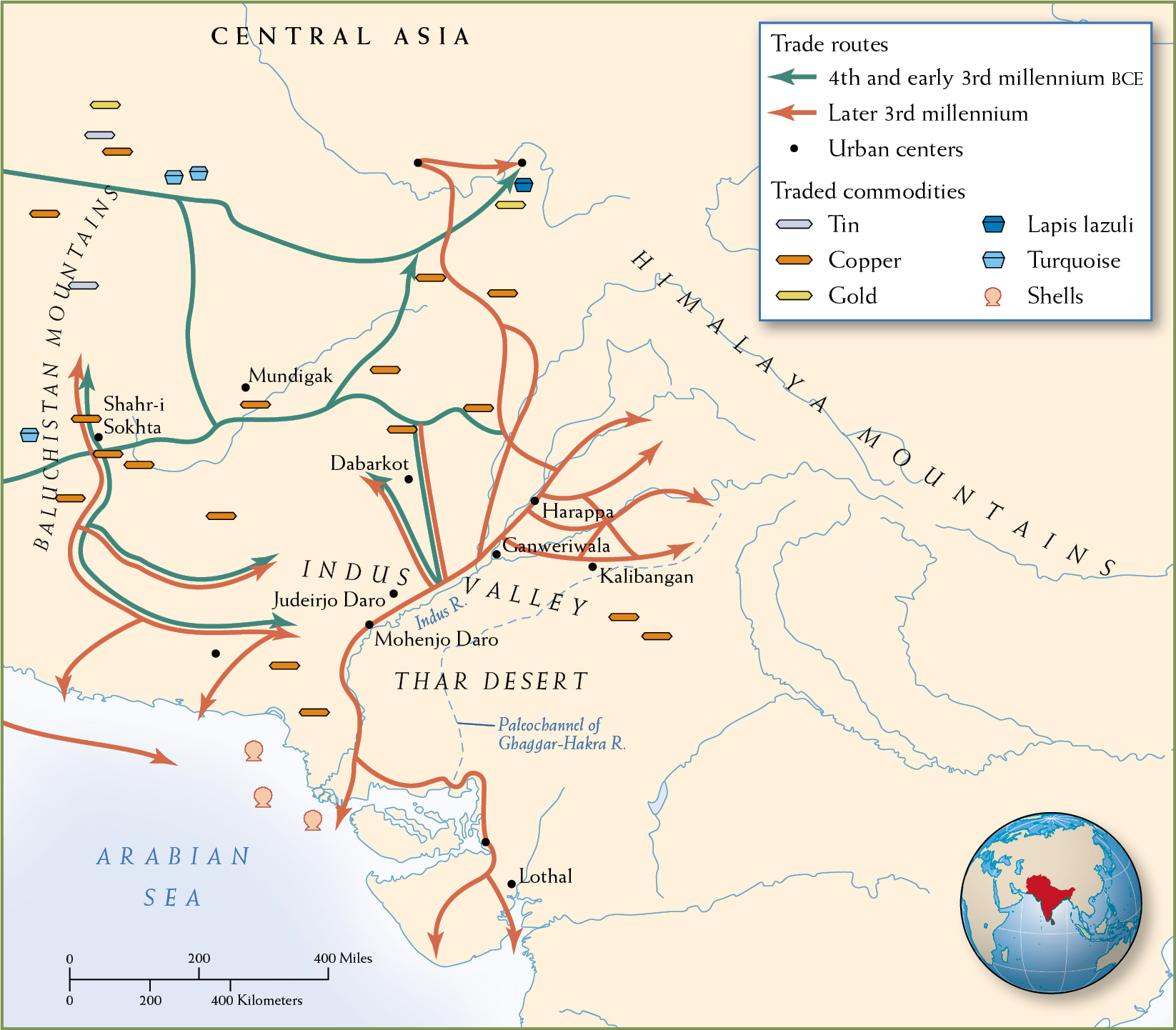

Developments in the Indus basin reflected an indigenous (local) tradition combined with strong influences from Iranian plateau peoples, as well as indirect influences from distant cities on the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Villages appeared before 5000 BCE on the Iranian plateau west of the Indus. By the early third millennium BCE, with changing river regimes, frontier villages began to spread eastward to the fertile banks of the Indus River and its tributaries. (See Map 2.5.) These river-basin settlements soon yielded agrarian surpluses that supported greater wealth, more trade with neighbors, and public works. In due course, urbanites of the Indus region and the Harappan peoples began to fortify their cities and to undertake public works similar in scale to those in Mesopotamia, but strikingly different in function.

The Indus Valley environment boasted many advantages—especially compared with the area near the Ganges River, the other great waterway of the South Asian landmass. The semitropical Indus Valley had plentiful water from melting snows in the Himalayas that ensured flourishing vegetation. The expansion of agriculture in the Indus basin depended on the river’s annual floods to replenish the soil and avert droughts (much as peoples in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China relied on their rivers). From June to September, the rivers inundated the plain. Once the waters receded, farmers planted wheat and barley. New evidence has suggested that the monsoons also brought seasonal flows of water into long-dried-up riverbeds (especially the so-called paleochannel of the Ghaggar-Hakra, a river that had dried up almost three thousand years before Harappan society began to thrive). This evidence poses a unique question about river-fueled society in the third millennium: How did the Harappan settlements clustered along this paleochannel to the east of the Indus River harness a seasonal flow of water into an otherwise-dried-up riverbed, as compared with a year-round river?

Whether along the year-round-flowing Indus or the seasonal flows of water in the Ghaggar-Hakra paleochannel, farmers planted wheat and barley, harvesting the crops the next spring. Harappan villagers also improved their tools of cultivation. Researchers have found evidence of furrows, probably made by plowing, that date to around 2600 BCE. The rise of the Harappan state along with increased agricultural production freed many inhabitants from producing food and enabled them to specialize in other activities.

In time, rural wealth produced urban splendor. More abundant harvests, now stored in large granaries, brought migrants into the area and supported expanding populations. By 2500 BCE, cities began to replace villages throughout the Indus River valley, and within a few generations, towering granaries marked the urban skyline. Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, the two largest cities, each covered a little less than half a square mile and may have housed 35,000 residents. Even more interesting is the smaller city of Dholavira, recently discovered. Its inhabitants quarried, transported, and worked stone, and its city builders erected large water reservoirs inside fortified city walls. As in Mesopotamia, such population densities were unprecedented departures from the more common agrarian villages or nomadic communities, which remained self-sufficient.

Harappan cities sprawled across a vast floodplain covering 500,000 square miles—two or three times the Mesopotamian cultural zone—and archaeologists thus far have uncovered more than 1,500 sites. At the height of their development, the Harappan peoples reached the edge of the Indus ecological system and encountered the cultures of northern Afghanistan, the inhabitants of the desert frontier, the nomadic hunters and gatherers to the east, and the traders to the west. Although scholars know less about Harappan society than about Mesopotamia or ancient Egypt, what they know about Harappan urban culture and trade routes is impressive.

Harappan City Life and Writing

The layout of Harappan cities and towns followed a well-planned pattern: a fortified citadel housing public facilities alongside a large residential area. The main street running through the city had covered drainage on both sides, with house gates and doors opening onto back alleys. Citadels were likely centers of political and ritual activities. At the center of the citadel of Mohenjo Daro was the famous great bath, a brick structure 39.3 feet by 23 feet and 9.8 feet deep. Flights of steps led to the bottom of the bath, while other stairs went up to a level of rooms surrounding it. The bath was sealed with mortar and bitumen (a sticky, tarlike form of petroleum), and its water came from a large well nearby. The water drained out through a channel leading to lower land. The location, size, and quality of the structure all suggest that the bath was for public bathing rituals.

MAP 2.5 | The Indus River Valley in the Third Millennium BCE

Historians know less about the urban society of the Indus Valley in the third millennium BCE than they do about its contemporaries in Mesopotamia and Egypt, in part because of the absence of a written record. Recent scholarship has suggested the importance of a second seasonal flow (as opposed to a year-round river) in the channel of the long-dried-up Ghaggar-Hakra to the east of the Indus.

- Where were cities concentrated in the Indus Valley? Why do you think the cities were located where they were?

- How do the trade routes of the fourth and early third millennium BCE differ from those of the later third millennium BCE? What might account for those differences?

- What commodities appear on this map? What is their relationship to urban centers and trade routes?

The Harappans used brick extensively—in houses for notables, in city walls, and in underground water drainage systems. Workers used large ovens to manufacture the durable construction materials, which the Harappans laid so skillfully that basic structures remain intact to this day. While common construction materials were used throughout Harappan communities, the differences in the size of dwellings, particularly in urban settings, suggest that social distinctions existed. A well-built house of a wealthier family could be two to three stories high. It contained at least one interior courtyard and had private bathrooms, showers, and toilets that drained into municipal sewers. More typical dwellings in the cities were one-room apartments with shared bathrooms. Houses in small towns and villages were made of less durable and less costly sun-baked bricks, which are used throughout southern Eurasia even today.

The peoples of the Indus Valley developed a logographic system of writing made up of about 400 signs (far too many for an alphabetic system, which tends to have closer to thirty symbols). Without a bilingual or trilingual text, like the Behistun inscription for Sumerian cuneiform or the Rosetta Stone for Egyptian hieroglyphs, Indus Valley script has been impossible to decipher. Computer analysis, however, is helping researchers identify some features of the script and the pre-Indo-European language it might record. Even so, some scholars suggest that the signs might not represent spoken language, but rather be a nonlinguistic symbol system. Although a ten-glyph-long public inscription has been found at the Harappan site of the ancient city of Dholavira, nearly all of what remains of the Indus Valley script is to be found on a thousand or more stamp seals and small plaques excavated from the region. These seals and plaques may represent the names and titles of individuals rather than complete sentences. As of yet, there is no evidence that the Harappans produced historical records such as the King Lists of Mesopotamia and Egypt, thus making it impossible to chart a history of the rise and fall of dynasties and kingdoms. Hence, our knowledge of Harappa comes exclusively from archaeological reconstructions, reminding us that “history” is not what happened but only what we know about what happened.

Trade

The Harappans engaged in trade along the Indus River, through the mountain passes to the Iranian plateau, and along the coast of the Arabian Sea as far as the Persian Gulf and Mesopotamia. They traded copper, flint, shells, and ivory, as well as pottery, flint blades, and jewelry created by their craftworkers, in exchange for gold, silver, gemstones, and textiles. Trade was facilitated by standardized sets of weights and measures. Along with these goods came people bringing the major ideas and institutions of Harappan society to these surrounding cultures.

Some of the Harappan trading towns nestled in remote but strategically important places. Consider Lothal, a well-fortified port at the head of the Gulf of Khambhat (Cambay). Although distant from the center of Harappan society, it provided vital access to the sea and to valuable raw materials. Its many workshops processed precious stones, both local and foreign. Because the demand for gemstones was high in Mesopotamia, the Harappans knew that controlling their extraction and trade was essential to maintaining economic power. Carnelian, a precious red stone, was a local resource, but lapis lazuli had to come from what is now northern Afghanistan. So the Harappans built fortifications and settlements near its sources. Extending their frontier did not stop at gemstones. Because metals such as copper and silver also had strategic commercial importance, the Harappans established settlements near their copper mines as well.

The general uniformity in Harappan sites suggests a centralized and structured state. Unlike the Mesopotamians and the Egyptians, however, the Harappans apparently built neither palaces nor grand royal tombs nor impressive monumental structures. The elites expressed their elaborate urban culture in ways that did not proclaim their high standing, with the exception, in some cases, of more substantial private homes. As a result, the Harappans were apparently as unassuming as the Egyptians and Mesopotamians were boastful. This quality underscores the profound differences in ancient societies: they did not all value the same things, and they were not organized in the same ways. The advent of writing, urban culture, long-distance trade, and large cities did not always produce the same social hierarchies and the same ethos (a set of principles governing social and political relations). What the Indus River people show us is how much the urbanized parts of the world were diverging from one another, even as they borrowed from and imitated their neighbors.