TERRITORIAL STATES IN SOUTHWEST ASIA

Climate change and invasions by migrants also transformed the societies of Southwest Asia, and new territorial kingdoms arose in Mesopotamia and Anatolia (modern-day Iraq and Turkey, respectively). Here, as in Egypt, the drought at the end of the third millennium BCE was devastating. Harvests shrank, the price of basic goods rose, and the social order broke down. In southern Mesopotamia, transhumant herders (not chariot-driving nomads, as in Egypt) invaded cities, seeking grazing lands to replace those swallowed up by expanding deserts. A millennium of intense cultivation, combined with severe drought, brought disastrous consequences: rich soil in the river basin was depleted of nutrients; salt water from the Persian Gulf seeped into the marshy deltas, contaminating the water table; and the main branch of the Euphrates River shifted to the west. Many cities lost access to their fertile hinterlands and withered away. Mesopotamia’s center of political gravity shifted northward, away from the silted, marshy deltas of the southwestern heartland.

Transhumant herders may have been “foreigners” in the cities of Mesopotamia, but they were not strangers to them. Speaking a related Semitic language, they had always played an important role in Mesopotamian urban life and knew the culture of its city-states. These rural folk wintered in villages close to the river to water their animals, which grazed on fallow fields. In the scorching summer, they retreated to the cooler highlands. Their flocks provided wool for the vast textile industries of Mesopotamia, as well as leather, bones, and tendons for other crafted products. In return, the herders purchased crafted products and agricultural goods. They also paid taxes, served as warriors, and labored on public works projects. Yet despite being part of the urban fabric, they had few political rights within city-states.

Around 2000 BCE, Amorites (“westerners,” as the Mesopotamian city dwellers called them) from the western desert joined allies from the Iranian plateau to bring down the Third Dynasty of Ur, which had controlled all of Mesopotamia and southwestern Iran for more than a century. These Amorites founded the Old Babylonian dynasty centered on the southern Mesopotamian city of Babylon, near modern Baghdad. Other territorial states arose in Mesopotamia in the centuries that followed, sometimes with one dominating the entire floodplain and sometimes with multiple powerful kingdoms vying for territory. As in Egypt, a century of political instability followed the demise of the old city-state models. Here, too, pastoralists played a role in the restoration of order, increasing the wealth of regions they conquered and helping the cultural realm to flourish. The Old Babylonian kingdom expanded trade and founded territorial states with dynastic ruling families and well-defined frontiers. Pastoralists also played a key role in the development of territorial kingdoms in Anatolia.

Mesopotamia: A New Model of Kingship

The new rulers of Mesopotamia changed the organization of the state and promoted a distinctive culture as well as expanding trade. Herders-turned-urbanite-rulers mixed their own nomadic social organization with that of the formerly dominant city-states to create the structures necessary to support much larger territorial states. The basic social organization of the Amorites, out of which the territorial states in Mesopotamia evolved, was tribal (dominated by a ruling chief) and clan based (claiming descent from a common ancestor). In time, chieftains drew on personal charisma and battlefield prowess to become kings; kings allied with the merchant class and nobility for bureaucratic and financial support, and kingship became hereditary.

Over the centuries, powerful Mesopotamian kings expanded their territories and subdued weaker neighbors, inducing them to pay tribute in luxury goods, raw materials, and manpower as part of a broad confederation of polities under the kings’ protection. Control over military resources (access to metals for weaponry and, later, to herds of horses for pulling chariots) was necessary to gain dominance, but it was no guarantee of success. The ruler’s charisma also mattered. Unlike the more institutionalized Egyptian leadership, Mesopotamian kingdoms could vacillate from strong to weak, depending on the ruler’s personality.

The most famous Mesopotamian ruler of this period was Hammurabi (r. 1792–1750 BCE). The name Hammurabi was both Amorite and Akkadian, for the term hammu meant “family” in Amorite while rabi meant “great” in Akkadian. Continuously struggling with powerful neighbors, Hammurabi sought to centralize state authority and to create a new legal order. Using diplomatic and military skills to become the strongest king in Mesopotamia, Hammurabi made Babylon his capital and declared himself “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient” (Frayne, p. 341). He implemented a new system to secure his power, appointing regional governors to manage outlying provinces and to deal with local elites.

Hammurabi’s image as ruler mirrored that of the Egyptian pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom. The king was shepherd and patriarch of his people, responsible for proper preparation of the fields and irrigation canals and for his followers’ well-being. Such an ideal recognized that being king was a delicate balancing act. While he had to curry favor among powerful merchants and elites, he also had to meet the needs of the poor and disadvantaged—in part to avoid a reputation for cruelty and in part to gain a key base of support should the elites become dissatisfied with his rule.

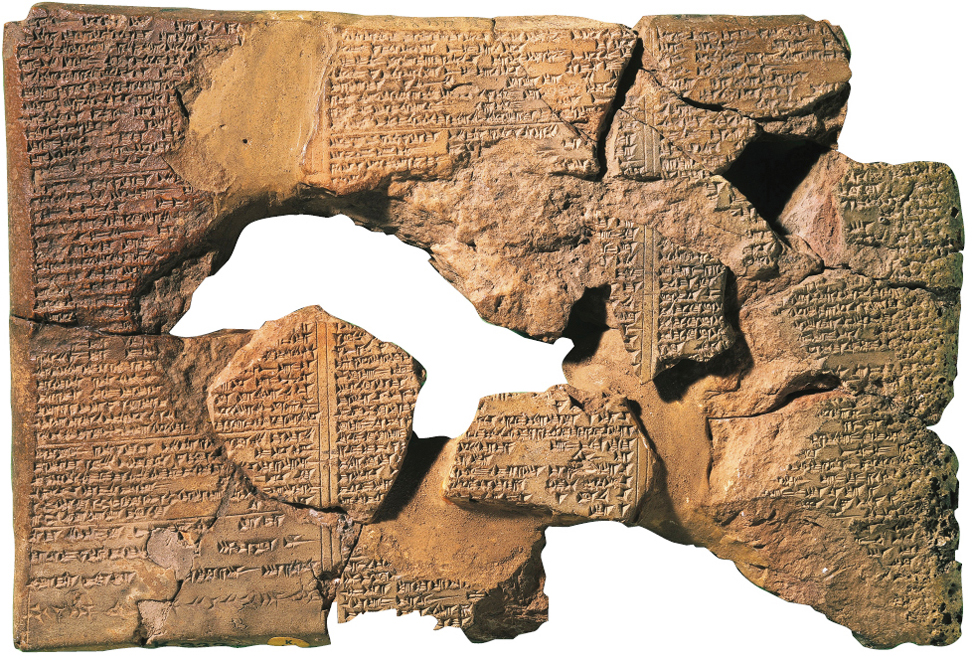

Hammurabi elevated this balancing act into an art form, encapsulated in a grand legal code—Hammurabi’s Code, with its “eye-for-an-eye,” if/then, reciprocity of crime and punishment. Much of the code itself was inscribed on a large stone stele, at the top of which was a portrait of Hammurabi himself, posing humbly before the sun god, Shamash, the patron of justice. Below this image came the laws, suggesting that they were handed down from the deity through a just, benevolent, and conquering ruler. The code began and concluded with the rhetoric of paternal justice. For example, Hammurabi concluded by describing himself as “the shepherd who brings peace, whose scepter is just.” He continued, “My benevolent shade was spread over my city, I held the people of the lands of Sumer and Akkad safely on my lap” (Roth, p. 133).

Hammurabi’s Code was a compilation of 282 edicts addressing crimes and their punishments. The laws dealt with theft, murder, professional negligence, and many other matters of daily life. The laws make it clear that governing public matters was man’s work, and upholding a just order was the supreme charge of rulers. Whereas the gods’ role in ordering the world was distant, the king was directly in command of ordering relations among people. Accordingly, the code elaborated in exhaustive detail the social rules that would ensure the kingdom’s peace through its primary instrument—the family. The code outlined the rights and privileges of fathers, wives, and children. The father’s duty was to treat his kin as the ruler would treat his subjects, with strict authority and care. Adultery was harshly punished, resulting in the drowning of the adulterous wife and her lover, unless the husband or king intervened.

The code also divided the people in the Babylonian kingdom into three classes: “free persons,” “dependents,” and “slaves.” Each class had an assigned value and distinct rights and responsibilities. While its eye-for-an-eye, tooth-for-a-tooth reciprocity is remarkable, the code also made it clear that Babylonia was a stratified society, in which some persons (and eyes and teeth!) were more valued than others. Punishments for offenses were determined by the status of the committer and that of the one who suffered. The code itself was inscribed in the last years of Hammurabi’s reign, after his conquests had created a larger state, and represented a way to celebrate the king’s achievements. By the end of his reign, he had established Babylon as the single great power in Mesopotamia and had reduced competitor kingdoms to mere vassals. Following his death, his sons and successors struggled to maintain control over a shrinking domain for another 155 years in the face of internal rebellions and foreign invasions. In 1595 BCE, Babylon fell to the Hittite king Hattusilis I.

The era of Hammurabi and his successors was a high point in the intellectual life of Mesopotamia, setting the stage for the achievements of the first-millennium Neo-Assyrians and Neo-Babylonians (see Chapter 4). In particular, mathematics and literature reached new heights, going far beyond what was needed for everyday applications. Religious life was also fundamentally altered. The city god of Babylon, Marduk, was raised to the level of a national god, becoming the primary cult of the land. It was Marduk who would confront Assur in the coming centuries in the struggle between north and south in the “land between two rivers.”

POWER AND CULTURE UNDER THE AMORITES Amorite kings of Babylonia commissioned public art and works projects and promoted institutions of learning. The court supported workshops for skilled artisans such as jewelers and sculptors, and it established schools for scribes, the transmitters of an expanding literary culture. To dispel their image as rustic foreigners and to demonstrate their familiarity with the region’s core values, new Mesopotamian rulers valued the oral tales and written records of the earlier Sumerians and Akkadians. Scribes copied the ancient texts and preserved their tradition. Royal hymns portrayed the king as a legendary hero of quasi-divine status.

Heroic narratives about legendary founders, based on traditional stories about the rulers of ancient Uruk, legitimized the new rulers. The most famous tale was the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the earliest surviving works of literature. Originally composed more than a millennium earlier, in the Sumerian language, this epic narrated the heroism of the legendary king of early Uruk, Gilgamesh. This epic is probably best known for the passage in which Gilgamesh seeks out advice from Utnapishtim, the survivor of a terrible flood, in a story that resonates with that of Noah from Genesis in the Hebrew scriptures. Utnapishtim’s flood story, however, is just one part of Gilgamesh’s epic, which describes the title character’s rivalry and, later, friendship with Enkidu and his quest for immortality after his friend Enkidu’s death. Preserved by scribes in royal courts through centuries, the epic offers an example of how the Mesopotamian kings invested in cultural production to explain important political relations, unify their people, and distinguish their subjects from those of other kingdoms.

TRADE AND THE RISE OF A PRIVATE ECONOMY Another feature of the territorial state in Mesopotamia was its shift away from economic activity dominated by the official and centralized city-state and toward independent private ventures. The new rulers designated private entrepreneurs rather than state bureaucrats to collect taxes. People paid taxes in the form of commodities such as grain, vegetables, and wool, which the entrepreneurs exchanged for silver. They, in turn, passed on the silver to the state after pocketing a percentage for their profit. This process generated more private activity and wealth as well as more revenues for the state.

Mesopotamia at this time was a crossroads for caravans leading east and west. When the region was peaceful and well governed, the trading community flourished. The ability to move exotic foodstuffs, valuable minerals, textiles, and luxury goods across Southwest Asia won Mesopotamian merchants and entrepreneurs a privileged position as they connected producers with distant consumers. Merchants also used sea routes for trade with the Indus Valley. Before 2000 BCE, mariners had charted the waters of the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden, the Persian Gulf, and much of the Arabian Sea. Now, during the second millennium BCE, shipbuilders figured out how to construct larger vessels and to rig them with towering masts and woven sails—creating truly seaworthy craft that could carry bulkier loads. Of course, shipbuilding required wood (particularly cedar from Phoenicia) as well as wool and other fibers (from the pastoral hinterlands) for sails. Such reliance on imported materials reflected a growing regional economic specialization and an expanding sphere of interaction across western Afro-Eurasia.

Doing business in Mesopotamia was profitable but also risky. If harvests were poor, cultivators and merchants could not meet their tax obligations and thus incurred heavy debts. The frequency of such misfortune is evident from the many royal edicts that annulled certain debts as a gesture of tax relief. Moreover, traders and goods had to pass through lands where some hostile rulers refused to protect the caravans. Thus, taxes, duties, and bribes flowed out along the entire route. If goods reached their final destination, they yielded large profits; if disaster struck, investors and traders had nothing to show for their efforts. As a result, merchant households sought to lower their risks by formalizing commercial rules, establishing insurance schemes, and cultivating extended kinship networks in cities along trade routes to ensure strong commercial alliances and to gather intelligence. They also cemented their ties with local political authorities. Indeed, the merchants who dominated the ancient city of Assur, on the Tigris, pumped revenues into the coffers of the local kingdom in the hope that its wealthy dynasts would protect their interests.

Anatolia: The Old and New Hittite Kingdoms (1800–1200 BCE)

Chariot warriors known as the Hittites established territorial kingdoms in Anatolia, northwest of Mesopotamia. Anatolia was an overland crossroads that linked the Black and Mediterranean Seas. Like other plateaus of Afro-Eurasia, it had high tablelands, was easy to traverse, and was hospitable to large herding communities. Thus, during the third millennium BCE, Anatolia became home to numerous political systems run by indigenous elites. These societies combined pastoral lifeways, agriculture, and urban commercial centers. Before 2000 BCE, peoples speaking Indo-European languages began to enter the plateau, probably coming from the steppe lands north and west of the Black Sea. The newcomers lived in fortified settlements and often engaged in regional warfare, and their numbers grew. They also borrowed extensively from the cultural developments of Southwest Asian urban cultures, especially from Mesopotamia.

In the early second millennium BCE, the chariot warrior groups of Anatolia grew powerful on the commercial activity that passed through the region. Chief among them were the Hittites. Hittite lancers and archers rode chariots across vast expanses to plunder their neighbors and demand taxes and tribute. In the seventeenth century BCE, the Hittite leader Hattusilis I unified these chariot aristocracies, secured his base in Anatolia, defeated the kingdom that controlled northern Syria, and then campaigned along the Euphrates River. His grandson and successor, Mursilis I, sacked Babylon in 1595 BCE. The Hittites ultimately built their capital at Hattusa, in central Anatolia, complete with massive walls, a monumental gate with lions carved into it, multiple temples and granaries, and a palace. Near Hattusa, the rock-cut sanctuary of Yazilikaya contains reliefs of gods and goddesses marching in procession, as well as images of Hittite kings.

Two centuries later, the Hittites enjoyed another period of political and military success. In 1274 BCE, they fought the Egyptians under the pharaoh Ramses II at the Battle of Qadesh (in modern Syria), the largest and best-documented chariot battle of antiquity. Both sides claimed victory. The treaty that records reciprocal promises of nonaggression by the Egyptians and Hittites nearly fifteen years after the battle is the oldest surviving peace treaty, and a replica of it is displayed at the United Nations. Soon after Qadesh, the Egyptian forces withdrew from the region. Hittite control—spanning from Anatolia across the region between the Nile and Mesopotamia—was central to balancing power among the territorial states that grew up in the river valleys.

A Community of Major Powers (1400–1200 BCE)

Between 1400 and 1200 BCE, the major territorial states of Southwest Asia and Egypt perfected instruments of international diplomacy. A cache of 350 letters, referred to by modern scholars as the Amarna letters after the present-day Egyptian village of Amarna, where they were discovered, offers intimate views of the interactions among the powers of Egypt and Southwest Asia. The letters include communications between Egyptian pharaohs and various leaders of Southwest Asia, including Babylonian and Hittite kings. Many are in Akkadian (used by Babylonian bureaucrats), which served as the diplomatic language of this era.

The correspondence reveals a delicate balance of constantly shifting alliances among competing kings who were intent on maintaining their status and who knew that winning the loyalty of the small buffer kingdoms was crucial to political success. Powerful rulers referred to one another as brothers, suggesting not only a high degree of equality but also a desire to foster friendship among large states. Trade linked the regimes and was so vital to the economic and political well-being of rulers that if a commercial mission were plundered, the ruler of the area in which the robbery occurred assumed responsibility and offered compensation to the injured parties.

Formal treaties brought an end to military eruptions and replaced them with diplomatic contacts. In its more common form, diplomacy involved strategic marriages and the exchange of specialized personnel to reside at the court of foreign territorial states. Gifts also strengthened relations among the major powers and signaled a ruler’s respect for his neighbors. Rulers had to acknowledge the gesture by reciprocating with gifts of equal value. The states even employed the practice of extradition, making it difficult for a criminal to flee from one territory and find safe haven in another.

Between 1400 and 1200 BCE, the major territorial states of Southwest Asia and Egypt perfected instruments of international diplomacy that have stood the test of time and inspired later leaders. The result was that rulers used treaties and negotiations rather than the battlefield to settle differences. Moreover, each state knew its place in the political pecking order. It was an order that depended on constant diplomacy, based on communication, treaties, marriages, and the exchange of gifts. As nomadic peoples combined with settled urban polities to create new territorial states in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia, and as those territorial states came into contact with one another through trade, this diplomacy was vital to maintaining the interactions in this community of major powers in Southwest Asia.

Glossary

- Amorites

- Name, which means “westerners,” used by Mesopotamian urbanites to describe the transhumant herders who began to migrate into their cities in the late third millennium BCE.

- Hammurabi’s Code

- Legal code created by Hammurabi (r. 1792–1750 BCE). The code divided society into three classes—free, dependent, and enslaved—each with distinct rights and responsibilities.

- Hittites

- An Anatolian chariot warrior group that spread east to northern Syria, though they eventually faced weaknesses in their own homeland. Rooted in their capital at Hattusa, they interacted with contemporary states both violently (as at the Battle of Qadesh against Egypt) and peacefully (as in the correspondence of the Amarna letters).