![]() Indo-European Migrations

Indo-European Migrations

NOMADS AND THE INDUS RIVER VALLEY

Territorial states emerged more slowly in the Indus River valley than they did in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Late in the third millennium BCE, drought ravaged the Indus River valley as it did other regions. By 1700 BCE, the population of the old Harappan heartland had plummeted. Here, too, around 1500 BCE, yet another group of nomadic peoples, calling themselves Aryans (“respected ones”), emerged from their homelands in the steppes of Inner Eurasia. In contrast with developments in Egypt, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia, these pastoral nomads were unable to establish large territorial states.

Crossing the northern highlands of central Asia through the Hindu Kush, they descended into the fertile Indus River basin (see Map 3.3) with large flocks of cattle and horses. Their priests offered chants from the Rig-Veda while sacrificing some of their livestock to their gods. Known collectively as the Vedas (“knowledge”), these hymns served as the most sacred texts for the newcomers, who have been known ever since as the Vedic peoples. They also arrived with an extraordinary language, Sanskrit (a term that etymologically means “perfectly made”). It is one of the earliest known Indo-European languages, having the same source as many of the European languages, including Greek, Latin, English, French, and German.

Like other nomads from the northern steppe, Vedic peoples brought domesticated animals—especially horses, which pulled their chariots and established their military superiority. Not only were they superb horse charioteers, but they were also masters of copper and bronze metallurgy and wheel making. Their expertise in these areas enabled them to produce the very chariots that transported them into their new lands.

The Vedic peoples were deeply religious. They worshipped a host of deities, the most powerful of which were the sky god and the gods that represented horses. They were confident that their chief god, Indra (the deity of war), was on their side. The Vedic peoples also brought elaborate rituals of worship, which set them apart from the indigenous populations. Perhaps the most striking of these was the year-long Ashvamedha, a ritual that culminated in an elaborate horse sacrifice that reinforced the power and territorial claims of the leader. As with many Afro-Eurasian migrations, the outsiders’ arrival led to fusion as well as to conflict. While the native-born peoples eventually adopted the newcomers’ language, the newcomers themselves took up the techniques and rhythms of agrarian life.

The Vedic peoples used the Indus Valley as a staging area for migrations throughout the northern plain of South Asia. As they mixed agrarian and pastoral ways and borrowed technologies (such as ironworking) from farther west, their population expanded and they began to look for new resources. With horses, chariots, and iron tools and weapons, they marched south and east. By 1000 BCE, they reached the southern foothills of the Himalayas and began to settle in the Ganges River valley. Five hundred years later, they had settlements as far south as the Deccan plateau.

Each wave of occupation involved violence, but the invaders did not simply dominate the indigenous peoples. Instead, the confrontations led them to embrace many of the ways of the vanquished. Although the Vedic peoples despised the local rituals, they were in awe of the inhabitants’ farming skills and knowledge of seasonal weather. These they adapted even as they continued to expand their territory. They built huts constructed from mud, bamboo, and reeds. They refined the already sophisticated production of beautiful carnelian stone beads, and they further aided commerce by devising standardized weights. In addition to raising domesticated animals, they sowed wheat and rye on the Indus plain, and they learned to plant rice in the marshy lands of the Ganges River valley. Later they mastered the use of plows with iron blades, an innovation that transformed the agrarian base of South Asia.

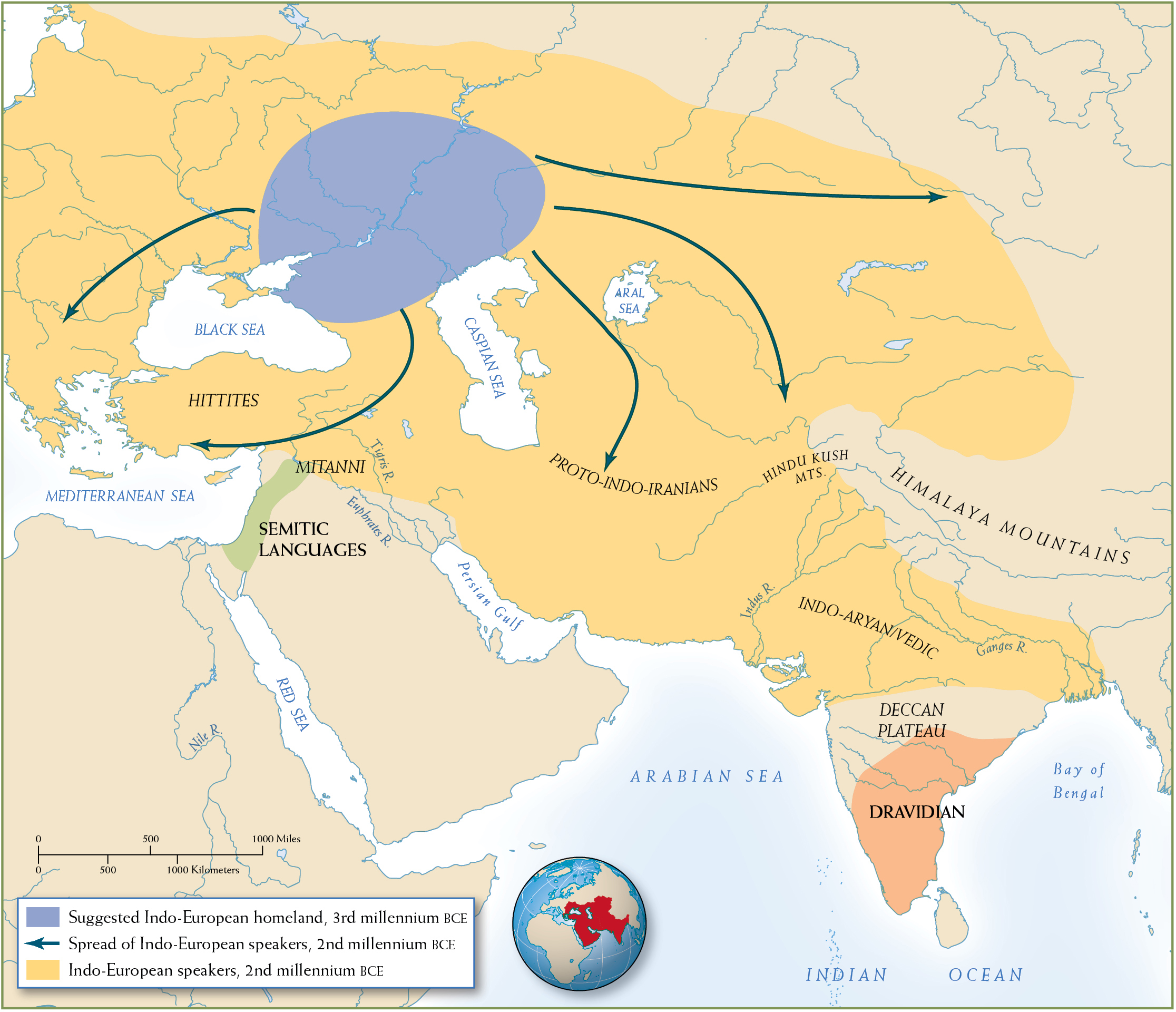

MAP 3.3 | Indo-European Migrations, Second Millennium BCE

One of the most important developments of the second millennium BCE was the movement of Indo-European peoples.

- Where did the Indo-European migration originate?

- Where did Indo-European migrations spread to during this time?

- How do these migrations relate to the Afro-Eurasian developments that are traced in this chapter?

The turn to settled agriculture was a major shift for the pastoral Vedic peoples. After all, their staple foods had always been dairy products and meat, and they were used to measuring their wealth in livestock (horses were most valuable, and cows were more valuable than sheep). Moreover, because they could not breed their prized horses in South Asia’s semitropical climate, they initiated a brisk import trade from central and Southwest Asia.

As the Vedic peoples filled the relative void left by the collapse of the Harappans and adapted to their new environment, their initial political organization took a somewhat different course from that of Southwest Asia. Whereas competitive kingdoms dominated the landscape in Southwest Asia, competitive and balanced regimes were slower to emerge in South Asia. The result was a slower process of political integration.

Glossary

- Vedic peoples

- Indo-European nomadic group who migrated from the steppes of Inner Asia around 1500 BCE into the Indus basin, on to the Ganges River valley, and then as far south as the Deccan plateau, bringing with them their distinctive religious ideas (Vedas), Sanskrit, and domesticated horses.