![]() Austronesian Migrations

Austronesian Migrations

MICROSOCIETIES IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC, THE AEGEAN, NORTHERN EUROPE, AND THE AMERICAS

As environmental circumstances drove pastoral nomads and transhumant herders toward settled agriculturalists, leading ultimately to the development of powerful and somewhat intertwined territorial states in Egypt, Southwest Asia, the Indus River valley, and Shang China, other pressures drove migrations across the South Pacific, the Aegean, the northern frontier of Europe, and the Americas. These migrations led to the development after 2000 BCE of microsocieties—small-scale, fragmented, and dispersed communities that had limited interactions with others.

The South Pacific (2500 BCE–400 CE)

As Afro-Eurasian populations grew and migration and trade brought cultures together, some peoples took to the waters in search of opportunities or refuge. By comparing the vocabularies and grammatical similarities of languages spoken today by the tribal peoples in Taiwan, the Philippines, and Indonesia, scholars can trace the ancient Austronesian-speaking peoples back to coastal South China in the fourth millennium BCE. A first wave of migrants reached the islands of Polynesia. A second wave from Taiwan around 2500 BCE again reached Polynesia and then went beyond into the South Pacific. By 2000 BCE, these peoples had replaced the earlier inhabitants of the East Asian coastal islands, the hunters and gatherers known as the Negritos, who had migrated south from the Asian landmass around 28,000 BCE, during an ice age when the coastal Pacific islands were connected to the Asian mainland.

SEAFARING SKILLS Using their remarkable double-outrigger canoes, which were 60 to 100 feet long and bore huge triangular sails, the early Austronesians crossed the Taiwan Straits and colonized key islands in the Pacific. Their vessels were much more advanced than the simple dugout canoes used in inland waterways. In good weather, double-outrigger canoes could cover more than 120 miles in a day. The invention of a stabilization device for deep-sea sailing sometime after 2500 BCE triggered further Austronesian expansion into the Pacific. By 400 CE, these nomads of the sea had reached most of the South Pacific except for Australia and New Zealand.

Their seafaring skills enabled the Austronesians to monopolize trade wherever they went. Among their craftworkers were potters, who produced distinctive Lapita ware (bowls and vessels) on offshore islets or in coastal villages. Archaeological finds reveal that these canoe-building people also conducted interisland trade in New Guinea after 1600 BCE, reaching Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga according to the evidence from pottery fragments and the remains of domesticated animals.

ENVIRONMENT AND CULTURE Pottery, stone tools, and domesticated crops and pigs characterized Austronesian settlements throughout the coastal islands and in the South Pacific. These cultural markers reached the Philippines from Taiwan. By 2500 BCE, according to archaeologists, the same cultural features had spread to the islands of Java, Sumatra, Celebes, Borneo, and Timor. Austronesians arrived in Java and Sumatra in 2000 BCE; by 1600 BCE, they were in Australia and New Guinea, although they failed to penetrate the interior, where descendants of the indigenous peoples still live. The Austronesians then ventured farther eastward into the South Pacific, apparently arriving in Samoa and Fiji in 1200 BCE and on mainland Southeast Asia in 1000 BCE. (See Map 3.5.)

MAP 3.5 | Austronesian Migrations

The Pacific Ocean saw many migrations from East Asia.

- Where did the Austronesian migrants come from? What were the boundaries of their migration? Trace the stages of Austronesian migration over time. Why do you think these migrations took place over such a long time period?

- Why, unlike other migratory people during the second millennium BCE, did Austronesian settlers in Polynesia become a world apart?

Equatorial lands in the South Pacific have a tropical or subtropical climate and, in many places, fertile soils containing nutrient-rich volcanic ash. In this environment, the Austronesians cultivated dry-land crops (yams and sweet potatoes), irrigated crops (more yams, which grew better in paddy fields or in rainy areas), and harvested tree crops (breadfruit, bananas, and coconuts). In addition, colonized areas beyond the landmass, such as the islands of Indonesia, had labyrinthine coastlines rich in maritime resources, including coral reefs and mangrove swamps teeming with wildlife. Island-hopping led the adventurers to encounter new food sources, but the shallow waters and reefs offered sufficient fish and shellfish for their needs.

In the South Pacific, the Polynesian descendants of the early Austronesians shared a common culture, language, technology, and store of domesticated plants and animals. These later seafarers came from many different island communities (hence the name Polynesian, “belonging to many islands”), and after they settled down, their numbers grew. Their crop surpluses allowed more densely populated communities to support craft specialists and soldiers. Most settlements boasted ceremonial buildings to promote local solidarity and forts to provide defense. On larger islands, communities often cooperated and organized workforces to enclose ponds for fish production and to build and maintain large irrigation works for agriculture. In terms of political structure, Polynesian communities ranged from tribal or village units to multi-island alliances that sometimes invaded other areas.

The Austronesians reached the Marquesas Islands in the central Pacific, strategically located for northern and southern exploration, around 200 CE. Over the next few centuries, some moved on to Easter Island to the south and Hawaii to the north. The immense 30-ton stone structures on Easter Island represent the monumental Polynesian architecture produced after their arrival. In separate migrations they traversed the Indian Ocean westward and arrived at the island of Madagascar by the sixth century CE. Along the way, they transmitted crops such as the banana to East Africa.

The expansion of East Asian peoples throughout the South Pacific and their trade back and forth did not, however, integrate the islands into a mainland-style culture. Expansion could not overcome the tendency of these microsocieties, dispersed across a huge ocean, toward fragmentation and isolation.

The Aegean World (2000–1200 BCE)

In the region around the Aegean Sea (the islands and the mainland of present-day Greece), no single power emerged before the second millennium BCE, but island microsocieties (the Minoans and the Mycenaeans) developed an expanding trade network and distinctive cultures. Settled agrarian communities developed into local polities linked only by trade and culture. Fragmentation was the norm—in part because the landscape had no great river-basin systems or large common plain. In its fragmentation, the island world of the eastern Mediterranean initially resembled that of the South Pacific.

As an unintended benefit of the lack of centralization, there was no single regime to collapse when the droughts arrived. Thus, in the second millennium BCE, peoples of the eastern Mediterranean did not struggle to recover lost grandeur. Rather, they enjoyed a remarkable though gradual development, making advances based on influences they absorbed from Southwest Asia, Egypt, and Europe. Residents of Aegean islands like Crete and Thera enjoyed extensive trade with the Greek mainland, Egypt, Anatolia, Syria, and Palestine. It was also a time of population movements from the Danube region and central Europe into the Mediterranean. Groups of these migrants settled in mainland Greece in the centuries after 1900 BCE; modern archaeologists have named them Mycenaeans after the famous palace at Mycenae, in the Greek Peloponnese, that dates to this era. Soon after settling in their new environment, the Mycenaeans turned to the sea to look for resources and interaction with their neighbors.

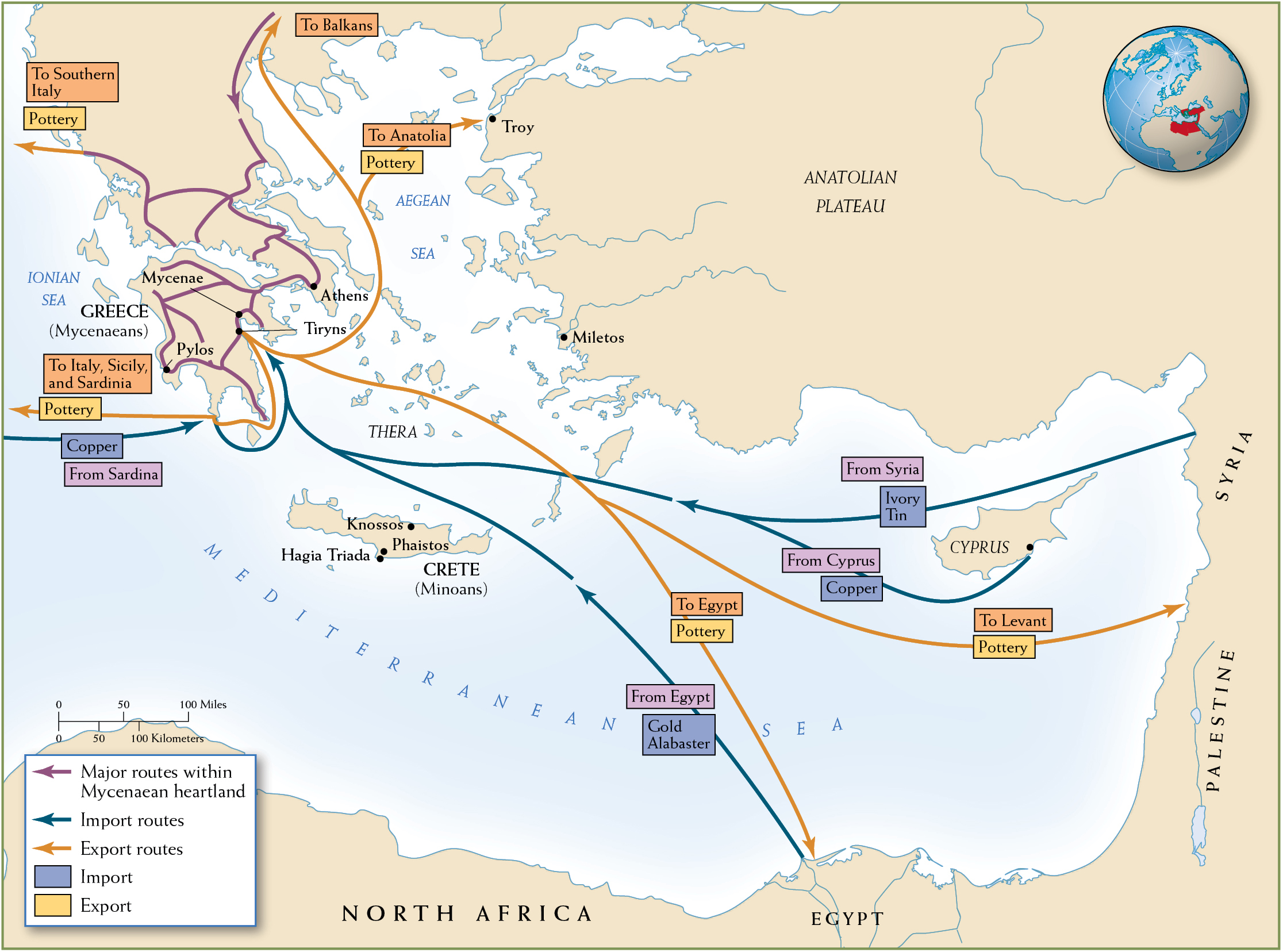

At the outset, the main influence on the Aegean world came from the east by sea. As the institutions and ideas that had developed in Southwest Asia moved westward, they found a ready reception along the coasts and on the islands of the Mediterranean. These innovations followed the sea currents, moving up the eastern seaboard of the Levant, then to the island of Cyprus and along the southern coast of Anatolia, and then westward to the islands of the Aegean Sea and to Crete. Trade was the main source of eastern influences, with vessels carrying cargoes from island to island and up and down the commercial centers along the coast. (See Map 3.6.) Mediterranean trade centered on tin from the east and readily available copper, both essential for making bronze (the primary metal in tools and weapons). Islands such as Cyprus and Crete, located in the midst of the active sea-lanes, flourished. Cyprus had large reserves of copper ore, which started to generate intense activity around 2300 BCE. By 2000 BCE, harbors on the southern and eastern sides of the island were shipping and transshipping goods, along with copper ingots, as far west as Crete, east to the Euphrates River, and south to Egypt.

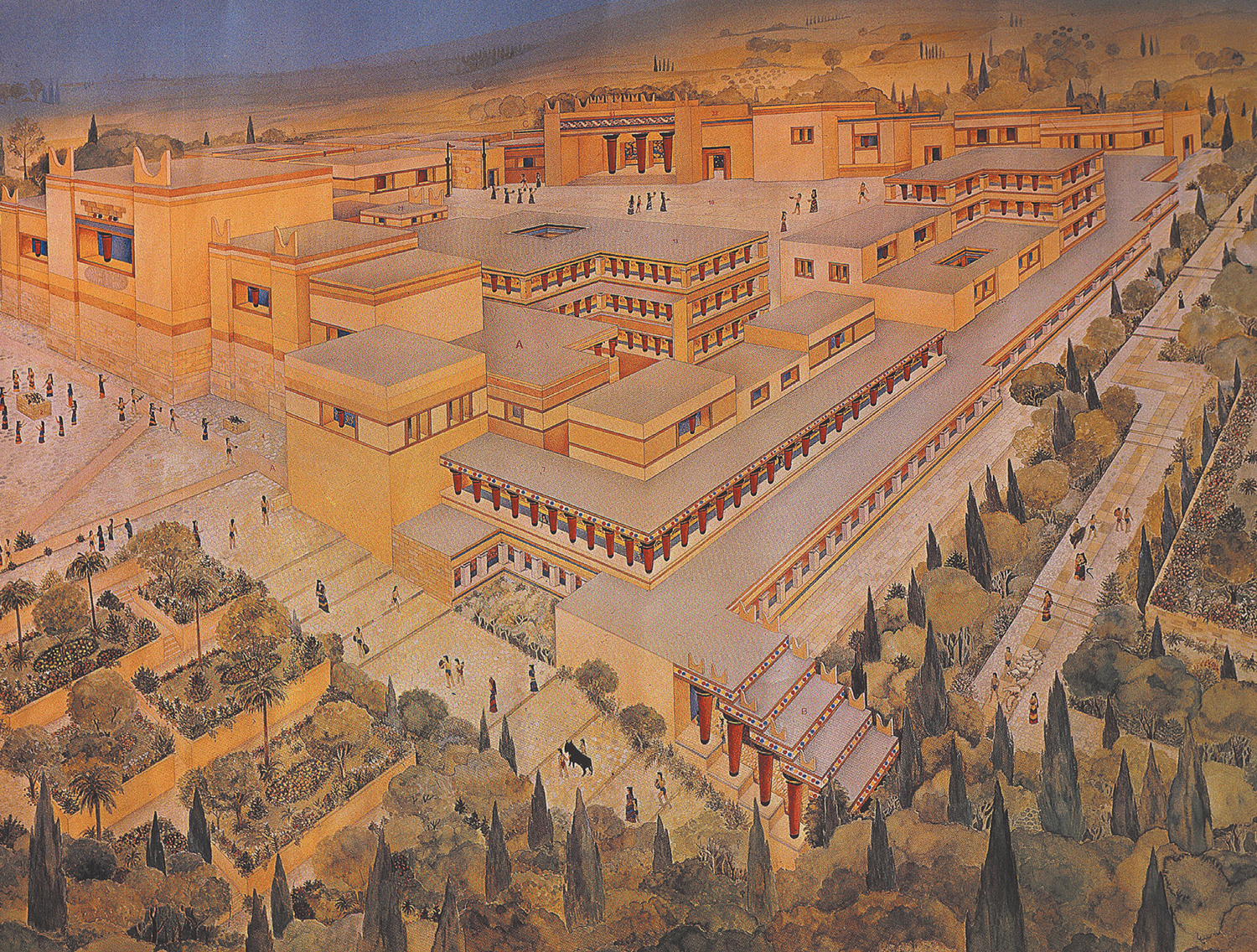

MINOAN CULTURE Crete, too, was an active trading node in the Mediterranean, with networks reaching as far east as Mesopotamia. Its culture reflected outside influences as well as local traditions. Around 2000 BCE, a large number of independent palace centers began to emerge on Crete, at Knossos and elsewhere. Scholars have named the people who built these elaborate centers the Minoans, after the legendary King Minos, who may have ruled Crete at this time. The Minoans sailed back and forth across the Mediterranean, and by 1600 BCE they were colonizing other Aegean islands as trading and mining centers. The Minoans’ wealth soon became a magnet for the Mycenaeans, their mainland competitors, who took over Crete around 1400 BCE.

MAP 3.6 | Trade in the Eastern Mediterranean World

Greece, Egypt, and Cyprus were trade hubs in the eastern Mediterranean.

- What major commodities were traded in the eastern Mediterranean?

- Why did trade originally move from east to west?

- What role did geography play in the Mycenaeans’ defeat of the Minoans?

As the island communities traded with the peoples of Southwest Asia, they borrowed some ideas but also kept their own cultural traditions. In terms of borrowing, the monumental architecture of Southwest Asia found small-scale echoes in the Aegean world—notably in the palace complexes built on Crete between 1900 and 1600 BCE. The most impressive was at Knossos.

Worship on the islands focused on a female deity, the Lady, but there are no traces of large temple complexes similar to those in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Egypt. Nor, apparently, was there any priestly class of the type that managed the temple complexes of Southwest Asian societies. Moreover, it is unclear whether these island societies had full-time scribes.

The so-called Phaistos disk, found in the palace of the city of Phaistos on Crete and measuring just over 6 inches across, is arguably an example of early Minoan writing. Its 242 symbols, spiraling inward from the rim of the disk, were impressed into the clay using 45 different stamps, including a rosette, an ear of grain, olives, fish, and birds. Some have suggested that the text might record a calendar or (most recently) a prayer to a mother goddess; still others insist the text is too limited to be convincingly deciphered.

Perhaps not surprisingly for a fragmented microsociety, there was significant regional diversity within this small Aegean world. On Crete, the large, palace-centered communities controlled centrally organized societies with a high order of refinement. Confident in their wealth and power, Minoan rulers lived in sprawling, airy palaces that had no fortifications and no natural defenses. On Thera (modern Santorini), a small island to the north of Crete, a trading city was not centered on a major palace complex but rather featured private houses, with bathrooms including toilets and running water and other rooms decorated with exotic wall paintings. It was this same island of Thera that was the center of a catastrophic volcanic eruption in the mid-second millennium BCE that likely contributed to the decline of the Minoans.

MYCENAEAN CULTURE The Mycenaean culture was more war oriented than that of the peaceful, seafaring Minoans. When the Mycenaeans migrated to Greece from central Europe, they brought their Indo-European language, their horse chariots, and their metalworking skills. Their move was gradual, lasting from about 1850 to 1600 BCE, but ultimately they dominated the indigenous population. They maintained their dominance with their powerful weapon, the chariot, until 1200 BCE. The battle chariots and festivities of chariot racing described in the centuries-later epic poetry of Homer’s Iliad (recounting the legendary Trojan War in which Mycenaean Greeks attacked the city of Troy, in Anatolia) express memories of glorious chariot feats that echo Vedic legends from South Asia. Homer’s “Catalog of Greek Ships” (Iliad 2.494–759), detailing the many different Greek communities that sent ships of warriors to fight at Troy, also illustrates the diffuse and fragmented political situation, yet common culture and ideals, that bound together the Greek microsociety.

The Mycenaean material culture emphasized displays of weaponry, portraits of armed soldiers, and illustrations of violent conflicts. The main palace centers at Tiryns and Mycenae were the hulking fortresses of warlords surrounded by rough-hewn stone walls and strategically located atop large rock outcroppings. In these fortified urban hubs, a preeminent ruler (wanax) stood atop a complex bureaucratic hierarchy. At the heart of the palace society were scribes, who recorded in their Linear B script the goods and services allotted to local farmers, shepherds, and metalworkers, among others. Tombs of the Mycenaean elite contain many gold vessels and ostentatious gold masks. Amber beads in the tombs indicate that the warriors had contacts with inhabitants of northern European coniferous forest regions, whose trees secreted that highly valued resin.

Mycenaean expansion eventually overwhelmed the Minoans on Crete. The Mycenaeans created colonies and trading settlements, reaching as far as Sicily and southern Italy. The trade and language of these early Greek-speaking peoples created a veneer of unity linking the dispersed worlds of the Aegean Sea. Yet, at the close of the second millennium BCE, the eastern Mediterranean faced internal and external convulsions that ended the heyday of these microsocieties. Most notable was a series of migrations of peoples from central Europe who moved through southeastern Europe, Anatolia, and the eastern Mediterranean (see Chapter 4 for more on these Sea Peoples). The invasions, although often destructive, did not extinguish but rather reinforced the creative potential of this frontier area. Because theirs was a closed maritime world—in comparison with the wide-open Pacific—the Greek-speaking peoples around the Aegean quickly reasserted dominance in the eastern Mediterranean that the Austronesians did not match in Southeast Asia or Polynesia.

Europe: The Northern Frontier

The transition to settled agriculture and the raising of domesticated animals took longer in western Afro-Eurasia than in the rest of the landmass. Two millennia passed, from 5000 to 3000 BCE, before settled agriculture became the dominant economic form in Europe. In many areas, hunters and gatherers clung to their traditional ways. Even this frontier, however, saw occasional visits from peoples driving horse chariots during the second millennium.

Forbidding evergreen forests dominated the northern area of the far western stretches of Europe, and the area’s sparse population was slow to implement the new ways. The first agricultural communities were frontier settlements where pioneers broke new land. Surrounded by hunting and foraging communities, these innovators lived hard lives in harsh environments, overcoming their isolation only by creating regional alliances. Such arrangements were too unstable to initiate or sustain long-distance trade. These were not fertile grounds for creating powerful kingdoms.

The early European cultivators adopted the techniques for controlling plants and animals that Southwest Asian peoples had developed. But rather than establishing large, hierarchical, and centralized societies, the Europeans used these techniques to create self-sufficient communities. They did not incorporate the other cultural and political features that characterized the societies of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the eastern Mediterranean. Occasional innovations such as the working of metal (initially, copper), the manufacture of pottery, and the use of the plow had little impact on local conditions. Throughout this period, Europe was hardly a developed cultural center. Instead, it was a wild frontier.

Two significant changes affected the northern frontier: the domestication of the horse and the emergence of wheeled chariots and wagons, both achieved in the eastern steppe lands. Both became instruments of war, and both promoted adaptation to the grassy lands of inner and central Europe, where pasturing animals in large herds proved profitable. The success of this horse culture led to the creation of several new frontiers, including those of agriculturally self-sustaining communities.

The new agriculturalists faced constant challenges, not just within Europe but also to the east as they entered the rolling grasslands of central Eurasia. Their attempts to enter this zone usually met overpowering resistance by fierce men on horseback. The inhabitants of the steppe lands north of the Black Sea gradually shifted from a primitive agriculture to an economy based on the herding of animals. In this zone, the exploitation of the horse fostered a highly mobile culture in which whole communities moved on horseback or by means of large wheeled wagons. Because these pastoral nomads regularly sought out the richer agricultural lands in central Europe, there was constant hostility between the two worlds.

These struggles among settlers, hunters and gatherers, and nomadic horse riders bred cultures with a strong warrior ethos. The fullest development of this mounted horse culture occurred in the centuries after 1000 BCE, when the steppe-land Scythian peoples engaged in rituals (such as drinking blood) that forged bonds of blood brotherhood among warriors and heightened their aggressive behavior. This rough-and-tumble frontier gave its people an appetite to borrow more effective means of waging war. Europeans desired the nomadic people’s weaponry, and over time their dealings with the horsemen took the form of trade as well as warfare. The Europeans adopted horses and finer metalworking technologies from the Caucasus. Of course, such trade made their battles even more lethal. And while the connections between this frontier zone and other parts of the Afro-Eurasian world began to multiply, the frontier was still too dispersed and unruly to develop integrated kingdoms.

Recent fossil discoveries along the banks of the Tollense River, a narrow stream of water that flows through northern Germany toward the Baltic Sea, reveal that these societies were as ready to engage in deadly warfare as the empires already discussed in this chapter. Here, more than 4,000 warriors engaged in a territorial battle around 1200 BCE, using war clubs, spears, knives, and swords made of wood, flint, and the newly arrived and most deadly of the metals, bronze, with which warriors tipped their arrows. We know about this battle because archaeologists uncovered, lodged in nearby swampy marshes, the skeletal remains of men who had died from battle wounds. The excavation, which is ongoing and likely to provide more skeletons, so far has yielded the remains of 5 horses and 100 men. The scale of the battle astonished the researchers and prompted the excavation’s codirector to describe it as incomparable. The battle brought together warriors from distant regions, and the fossils to this day represent the only nonwritten, archaeological record of the ancient worlds’ most massive and lethal conflict. Even so, at a time when the rest of Afro-Eurasia was developing an interrelated network of large territorial states, Europe remained a land of war-making, small chieftainships.

Early States in the Americas

Across all the Americas, river valleys and coasts sheltered villages and towns drawing sustenance from the rich resources in their hinterlands. Hunting and gathering was still the main lifeway here. But without beasts of burden or domesticated animals to carry loads or plow fields, local communities produced limited surpluses. Local trade involved only luxuries and symbolic trade goods, such as shells, feathers, hides, and precious metals and gems.

In the Central Andes, however, archaeologists have found evidence of early state systems that transcended local communities to function as confederations, or alliances of towns. These were not as well integrated as many of the territorial states of Southwest Asia, the Indus Valley, and China; they were more like settlements in Europe and the eastern Mediterranean, where towns traded basic goods and in some cases cooperated to resist aggressors.

The region’s varied ecology promoted the development of such confederations. Along the arid coast of what is now Peru, fishermen harvested the currents teeming with large and small fish; this was a staple that, when dried, was hardly perishable and easy to transport. The rivers flowing down from the Andes fanned out through the desert, often carving out basins suitable for agriculture. And where the mountains rose from the Pacific, rainfall and higher altitudes favored extensive pasturelands. Here roamed wild llamas and alpacas—difficult as beasts of burden, but valued for their wool in textile production. Such ecological diversity within a limited area promoted greater trade among subregions and towns. Indeed, the interchange of manioc (root of the cassava plant), chili peppers, dried fish, and wool gave rise to the commercial networks that could support political ones.

Communities on the coast, in the riverbeds, or in the mountain valleys were small but numerous. They took shape around central plazas, most of which had large platforms with special burial chambers for elders and persons of importance. Clusters of dwellings surrounded these centers. Much of what we know about political and economic transactions among these communities—as well as long-distance trade and statecraft—comes from the offerings and ornaments left in the burial chambers. Painted gourds, pottery, and fine textiles illustrate the increasing contact between cultures, often bound in alliances. For instance, marriage between noble families could strengthen a pact or confederation.

One early site known as Aspero reveals how a local community evolved into a form of chiefship, with a political elite and diplomatic and trading ties with neighbors. Temples straddled the top of the central platform, and the large structure at the center boasted lavish ornamentation. Also, there is evidence that smaller communities around Aspero sent crops (fruits) and fish (anchovies) to Aspero as part of an intercommunity system of mutual dependence.

Not all politics among the valley peoples of Peru consisted of trade and diplomacy, however. In the Casma Valley, near the Pacific coast, a clay and stone architectural complex at Cerro Sechín has revealed a much larger sprawl of dwellings and plazas dating back to 1700 BCE. Around the community’s central structure stood a wall composed of hundreds of massive stone tablets, carved with ornate etchings of warriors, battles, prisoners, executions, and human body parts. The warriors’ clothing is simple and rustic, and the main weapon resembles a club. Clearly, warfare accompanied the first expressions of statecraft in the Americas.

Glossary

- microsocieties

- Small-scale, fragmented communities that had little interaction with others. These communities were the norm for peoples living in the Americas and islanders in the Pacific and Aegean from 2000 to 1200 BCE.