Global Agricultural Revolution

The Global Agricultural Revolution

In some parts of the world modern humans carried out an agricultural revolution on their own by developing agricultural techniques based on their specific environment. Others borrowed from the first innovators. The innovators were found in Southwest Asia, where control of water was decisive; the southern part of China in East Asia, where water controls and rice were critical; Africa, where farmers just below the Sahara Desert in a region known as the Sahel innovated and then carried their skills to West Africa and the Ethiopian highlands; and the Americas, which had the disadvantage of offering few animals that humans could domesticate. In contrast, the cultivators of western Europe were borrowers, learning from the first innovators of Southwest Asia. Even so, a broad array of patterns existed as humans settled down as farmers and herders.

More information

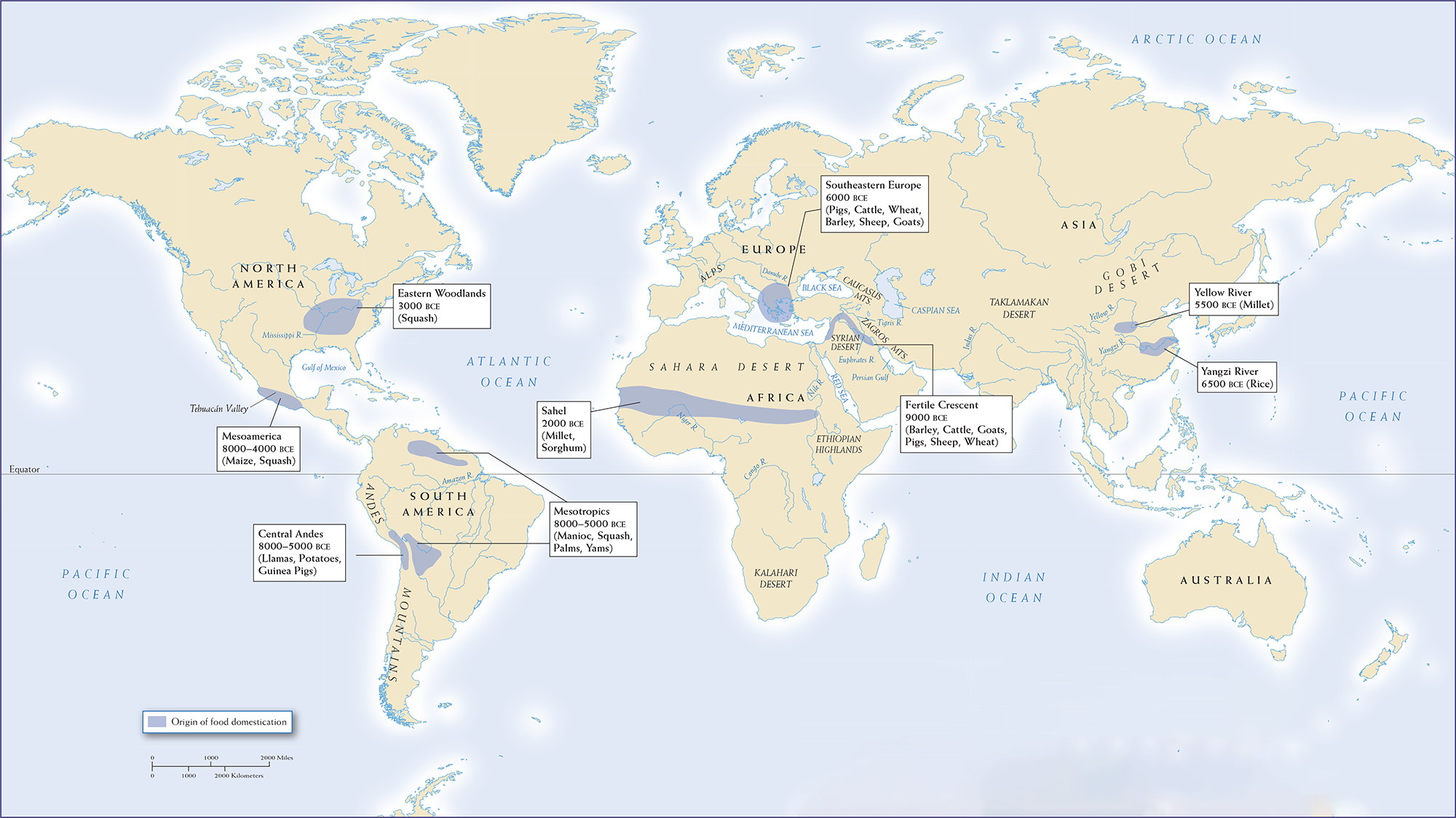

Map 1.4 is titled, “The Origins of Food Production and Animal Domestication.” Domestication of pigs, cattle, sheep, and goats first emerged in the Fertile Crescent in 8000 B C E, as did the cultivation of wheat and barley, all of these moving to Southeastern Europe in 6000 B C E, while llamas and guinea pigs were domesticated during those periods in the Central Andes. Millet is cultivated along the Yellow River in China from 5500 B C E, and rice along the Yangzhi River from 6500 B C E. Sorghum and millet were grown in the Sahel region of Africa beginning in 2000 B C E. Squash was cultivated in the Eastern Woodlands area of North America starting in 3000 B C E, while Maize and Squash emerged in Mesoamerica in Central America from 8000-4000 B C E. The Mesotropics regions of South America saw the cultivation of manioc, squash, palms, and yams emerge from 8000-5000 B C E, while the Central Andes region witnessed the domestication of llama and guinea pigs, as well as the cultivation of potatoes, beginning in 8000-5000 B C E.

MAP 1.4 | The Origins of Food Production and Animal Domestication

Agricultural production emerged in many regions at different times. The variety of patterns reflected local resources and conditions.

- In how many different locations, and at what different times, did agricultural production and animal domestication emerge? What is the range of crops and animals domesticated in each region?

- What specific geographic features (for instance, specific mountains, rivers, or latitudes) are common among these early food-producing areas? Do those geographic features appear to guarantee agricultural production?

- Why do you think agriculture emerged in certain areas and not in others?

More information

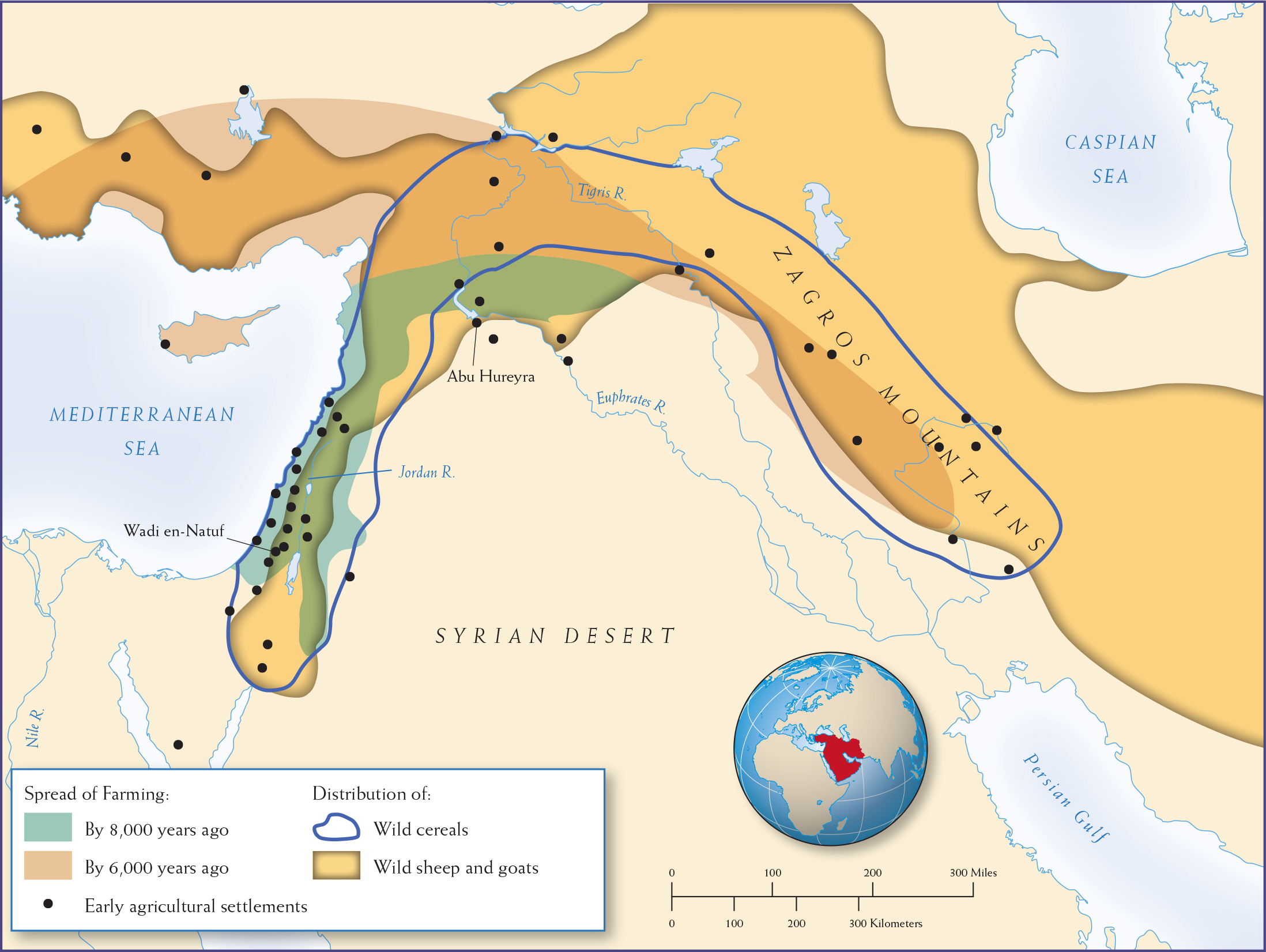

Map 1.5 is titled, “The Birth of Farming in the Fertile Crescent.” The map shows the spread of farming by 8,000 years ago, and then by 6,000 years ago, as well as the location of early agricultural settlements and the distribution of both wild cereals and wild sheep and goats. By 8,000 years ago, farming spread to a narrow band running east from the area around the Jordan River to the Fertile Crescent region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. By 6,000 years ago it spreads further north and west into Turkey and well as south and east to the edge of the Zagros Mountains. Early agricultural settlements are clustered in the area around the Jordan (including Wadi-en-Natuf) as well as along the nearby coast of the Mediterranean Sea and the Fertile Crescent (including Abu Hureyra). The distribution of wild cereals follows a slightly larger but similar distribution to that of agriculture 6,000 years ago (though it does not extend into Turkey), while wild sheep and goats are distributed in a much larger range that extends into western Turkey as well as throughout the Zagros Mountains and both south towards the Persian Gulf and east to the edge of the Caspian Sea.

MAP 1.5 | The Birth of Farming in the Fertile Crescent

Agricultural production occurred in the Fertile Crescent starting roughly in 9000 BCE. Though the process was slow, farmers and herders domesticated a variety of plants and animals, which led to the rise of large-scale, permanent settlements.

- Trace the region where the wild cereals were domesticated as well as the density of agricultural settlements. How does the region you traced relate to the reason this area is called the “Fertile Crescent”?

- What topographical features appear to influence the location of agricultural settlements and farming?

- What relationship existed between cereal cultivators and herders of goats and sheep?

Southwest Asia: Cereals and Mammals

The first agricultural revolution occurred in Southwest Asia in an area bounded by the Mediterranean Sea and the Zagros Mountains. Because of its rich soils and regular rainfall, this area played a leading role in the domestication of wild grasses and the taming of animals important to humans. Six large mammals—goats, sheep, pigs, cattle, camels, and horses—have been vital for meat, milk, skins (including hair), and transportation. Southwest Asians domesticated all of these except horses.

Around 9000 BCE, in the southern corridor of the Jordan River valley, humans began to domesticate the wild ancestors of barley and wheat. (See Map 1.5.) Various wild grasses were abundant in this region, and barley and wheat were the easiest to adapt to settled agriculture and the easiest to transport. Although the changeover from gathering wild cereals to regular cultivation took several centuries and saw failures as well as successes, by the end of the ninth millennium BCE, cultivators were selecting and storing seeds and then sowing them in prepared seedbeds. Moreover, in the valleys of the Zagros Mountains on the eastern side of the Fertile Crescent, similar experimentation was occurring with animals around the same time.

More information

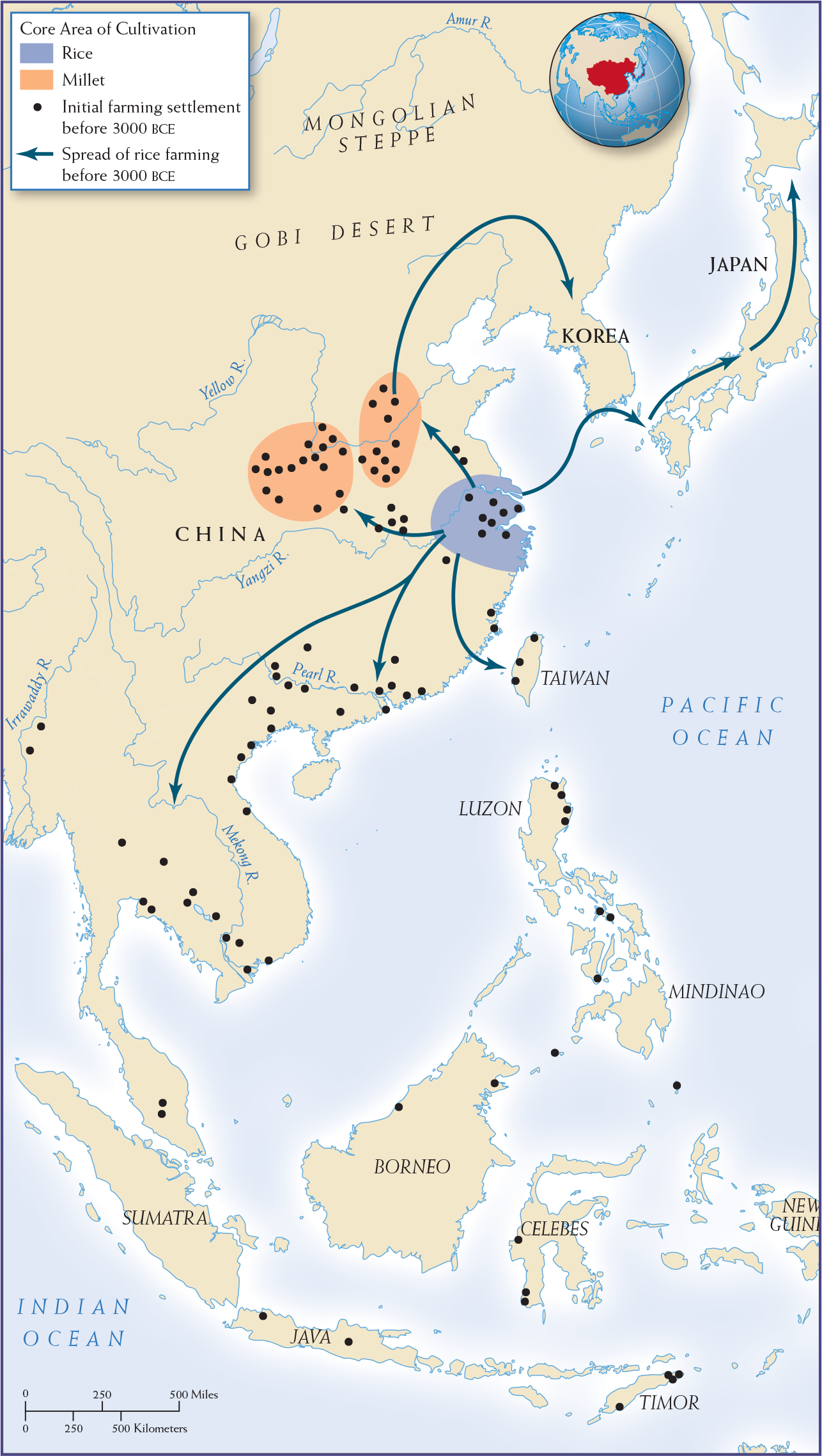

Map 1.6 is titled, “The Spread of Farming in East Asia.” Two core areas of millet cultivation are shown, both along China’s Yellow River, while the one core rice area is along the easternmost area of the Yangzi River where it meets the Pacific Ocean. Both those core areas have large numbers of initial farming settlements; farming settlements also exist in southern China by the Pearl River, as well as Southeast Asia in the areas of Vietnam and Cambodia, as well as the Indonesian islands and the Philippines. The map shows that rice farming spread from its core area north, east to Korea and Japan, as well as northwest to the core areas of millet cultivation, southeast to Taiwan, and further south, and west into southern China and Vietnam.

MAP 1.6 | The Spread of Farming in East Asia

Agricultural settlements appeared in East Asia between 6500 and 5500 BCE, several thousand years later than they did in the Fertile Crescent.

- According to this map, where did early agricultural settlements appear in East Asia?

- What two main crops were domesticated in East Asia? Where did each crop type originate, and to what regions did each spread?

- How did the physical features of these regions shape agricultural production?

East Asia: Rice and Water

A revolution in food production also occurred among the coastal dwellers in East Asia, although under different circumstances. (See Map 1.6.) Throughout this region, the spread of lakes, marshes, and rivers created habitats for population concentrations and agricultural cultivation. Two newly formed river basins became densely populated areas that were focal points for intensive agricultural development. These were the Yellow River, which deposited the fertile soil that created the North China plain, and the Yangzi River, which fed a land of streams and lakes in central China.

Rice in the south and millet in the north were for East Asia what barley and wheat were for Southwest Asia—staples adapted to local environments that humans could domesticate to support a large, sedentary population. Archaeologists have found evidence of rice cultivation in the Yangzi River valley in 6500 BCE and of millet cultivation in the Yellow River valley in 5500 BCE. Innovations in grain production spread through internal migration and wider contacts. When farmers migrated east and south, they carried domesticated millet and rice. In the south, they encountered strains of faster-ripening rice (originally from Southeast Asia), which they adopted. Rice was a staple in wetter South China, but millet and wheat (which spread to drier North China from Southwest Asia) were also fundamental to the food-producing revolution in East Asia.

More information

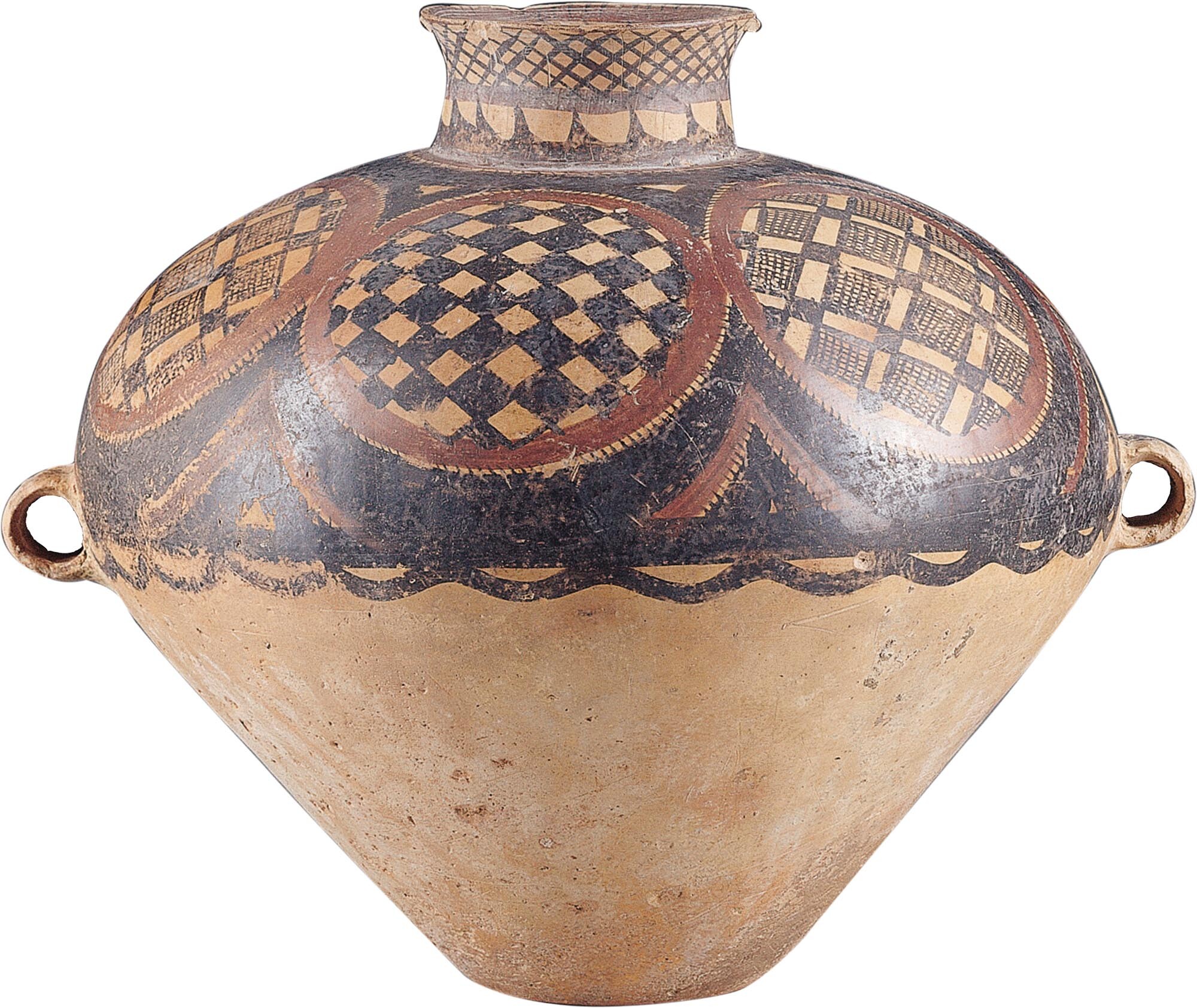

A large Yangshao pot with a wide mid-section and two small handles on either side. The top half is decorated with geometric designs in black and red.

Africa: The Race with the Sahara

The evidence for settled agriculture in the various regions of Africa is less clear. Most scholars think that the Sahel area (spanning the African landmass just south of the Sahara Desert) was likely where hunters and gatherers became settled farmers and herders without any borrowing. In this area, an apparent move to settled agriculture, including the domestication of large herd animals, occurred two millennia before it did along the Mediterranean coast in North Africa. From this innovative heartland, Africans carried their agricultural breakthroughs across the landmass.

It was in the wetter and more temperate locations of the vast Sahel, particularly in mountainous areas and their foothills, that villages and towns developed. These regions were lush with grassland vegetation and teeming with animals. Before long, the inhabitants had made sorghum, a cereal grass, their principal food crop. Residents constructed stone dwellings, underground wells, and grain storage areas. In one such population center, fourteen circular houses faced each other to form a main thoroughfare, or street. Archaeological investigations have unearthed remarkable rock engravings and paintings, often one composed on top of another, filling the cave dwellings’ walls. Many images portray in fascinating detail the changeover from hunting and gathering to pastoralism. Caves abound with pictures of cattle, which were a mainstay of these early men and women. The cave illustrations also depict daily activities of men and women living in conical huts, doing household chores, crushing grain on stone, and riding bareback on oxen (with women always sitting behind the men, potentially an early example of male superiority in some African societies).

More information

An artist’s drawing of the settlement at Çatal Hüyük shows several one-room houses arranged in a dense honeycomb design. The houses are white, rise to different heights, and face in different directions. Several roofs have been removed from the drawing to show the belongings inside.

The Sahel was colder and moister 10,000 years ago than it is today. As the world became warmer and the Sahara Desert expanded, around 4,000 years ago, this region’s inhabitants had to disperse and take their agricultural and herding skills into other parts of Africa. (See Map 1.7.) Some went south to the tropical rain forests of West Africa, while others trekked eastward into the Ethiopian highlands. In their new environments, farmers searched for new crops to domesticate. The rain forests of West Africa yielded root crops, particularly the yam and cocoyam, both of which became the principal life-sustaining foodstuffs. The ensete plant, similar to the banana, played the same role in the Ethiopian highlands. Thus, the beginnings of agriculture in Africa involved both innovation and diffusion.

The Americas: A Slower Transition to Agriculture

The shift to settled agriculture occurred more slowly in the Americas. When people entered the Americas around 23,000 years ago (21,000 BCE), they set off an ecological transformation but also adapted to unfamiliar habitats. The flora and fauna of the Americas were different enough to induce the early settlers to devise ways of living that distinguished them from their ancestors in Afro-Eurasia. Then, when the glaciers began to melt around 12,500 BCE and water began to cover the land bridge between East Asia and America, the Americas and their peoples truly became a world apart.

More information

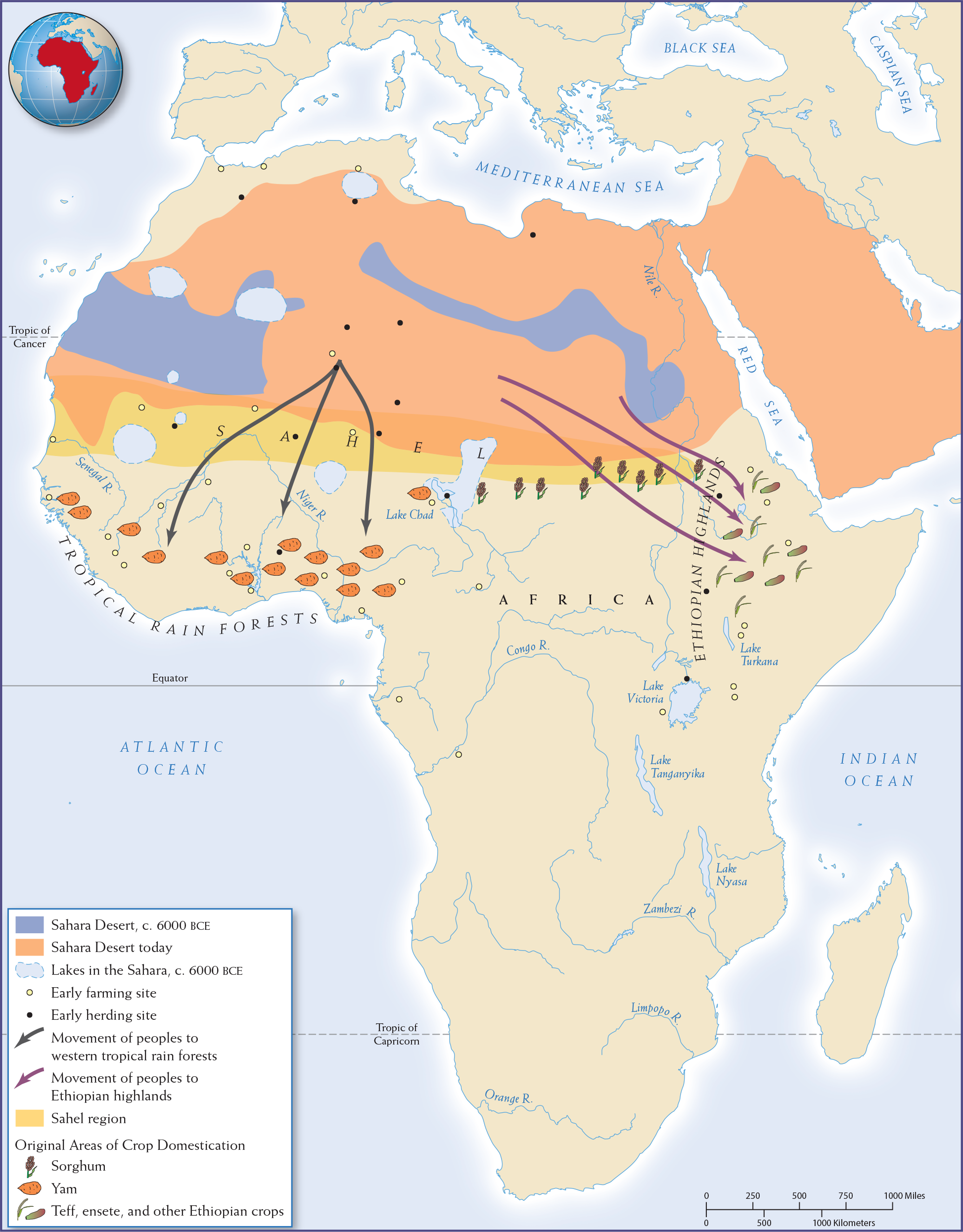

Map 1.7 is titled, “The Spread of Farming in Africa.” The map shows how societies living in the Sahel (the region south of the Sahara Desert that stretches between the West African coasts by the Senegal River all the way to the Ethiopian Highlands) developed their own version of agricultural production after 6000 B C E. It shows the extent of the Sahara circa 6000 B C E (only two sections, one in West Africa along the Tropic of Cancer, the other a thin strip stretching east to the Nile River), as well as a number of former lakes clustered in North and West Africa that have since dried up. This contrasts with the much larger Sahara today, which covers almost all of Africa above the Sahel, as well as Saudi Arabia. Early farming sites, most either in the western Sahel or south towards the Equator and the tropical rainforests of West Africa, are also shown, as well as herding sites further north in the area of Africa that was not desert circa 6000 but has become so today. The map also shows the movement of peoples south through the Sahel and to the tropical rainforests of West Africa where yams were originally domesticated. It also shows the movement of peoples from the edge of the eastern part of the former Sahara desert across those areas of the Sahel where sorghum is originally domesticated and into the Ethiopian Highlands where teff, ensete, and other Ethiopian crops are originally domesticated.

MAP 1.7 | The Spread of Farming in Africa

Societies living in the Sahel (the region south of the Sahara Desert) developed their own version of agricultural production after 6000 BCE.

- Why is the Sahel so important in the movement of peoples and ideas about crops? Why did farming spread in the directions that it did?

- What do you note about the location of farming and herding sites?

- How did the expansion of the Sahara Desert affect the diffusion of agriculture in the Sahel?

CLIMATIC CHANGE AND ADAPTATION The traditional narrative has been that early humans in America, called “Clovis people” after an archaeological site near Clovis, New Mexico (dating to around 11,000 BCE), used chipped blades and pointed spears to pursue their prey. New excavations, however, are unearthing even earlier evidence for human occupation in the Americas, with “pre-Clovis” sites ranging from Idaho and White Sands, New Mexico; to Pennsylvania and the southeastern United States; to Brazil and Chile. (See Map 1.2 for the complicated picture of human migration in the Americas.) Although scientists once thought that early hunting and gathering communities in the Americas had wiped out the large ice-age mammals in the Americas, recent research suggests that climatic change destroyed indigenous plants and trees—the feeding grounds of large prehistoric mammals. This left undernourished mastodons, woolly mammoths, bison, and other mammals vulnerable to human and animal predators. As in Afro-Eurasia, the arrival of a long warming cycle compelled those living in the Americas to adapt to different environments and to create new ways to support themselves. Thus, in the woodland area of the present-day northeastern United States, hunters learned to trap smaller wild animals for food and furs. To supplement the protein from meat and fish, these people also dug for roots and gathered berries. Even as most communities adapted to the settled agricultural economy, they did not abandon basic survival strategies of hunting and gathering.

Food-producing changes in the Americas were different from those in Afro-Eurasia because the Americas did not undergo the sudden cluster of innovations that revolutionized agriculture in Southwest Asia and elsewhere. Tools ground from stone, rather than chipped implements, appeared in the Tehuacán Valley in present-day eastern central Mexico by 6700 BCE, and evidence of plant domestication there dates back to 5000 BCE. But villages, pottery making, and sustained population growth came later. For many early American inhabitants, the life of hunting, trapping, and fishing went on as it had for millennia.

On the coast of what is now Peru, people found food by fishing and by gathering shellfish from the Pacific. Archaeological remains include the remnants of fishnets, bags, baskets, and textile implements; gourds for carrying water; stone knives, choppers, and scrapers; and bone awls (long, pointed spikes often used for piercing) and thorn needles. Thousands of villages likely dotted the seashores and riverbanks of the Americas. Some communities made breakthroughs in the management of fire, which enabled them to manufacture pottery; others devised irrigation and water sluices in floodplains; and some even began to send their fish catches inland in return for agricultural produce.

DOMESTICATION OF PLANTS AND ANIMALS The earliest evidence of plant experimentation in Mesoamerica (the region now known as Mexico and Central America) dates from around 8000 BCE, and it went on for a long time. Maize (corn), squash, and beans (first found in what is now central Mexico) became dietary staples. The early settlers foraged small seeds of maize, peeled them from ears only a few inches long, and planted them. Maize offered real advantages because it was easy to store, relatively imperishable, nutritious, and easy to cultivate alongside other plants. Nonetheless, it took 5,000 years for farmers to complete its domestication. Over the years, farmers had to mix and breed different strains of maize for the crop to evolve from thin spikes of seeds to cobs rich with kernels, with a single plant yielding big, thick ears to feed a growing permanent population. Thus, the agricultural changes afoot in Mesoamerica were slow and late in maturing. The pace was even more gradual in South America, where early settlers clung to their hunting and gathering traditions.

More information

A stone statue of a deity wearing a crown made up of cornhusks. It has large stylized eyebrows, a flat upturned nose, and large disk-shaped jewelry on its ears.

Across the Americas, the settled, agrarian communities found that legumes (beans), grains (maize), and tubers (potatoes) complemented one another in keeping the soil fertile and offering a balanced diet. Unlike the Afro-Eurasians, however, the settlers did not use domesticated animals as an alternative source of protein. In only a few pockets of the Andean highlands is there evidence of the domestication of tiny guinea pigs, which may have been tasty but unfulfilling meals. Nor did people in the Americas tame animals that could protect villages (as dogs did in Afro-Eurasia) or carry heavy loads over long distances (as cattle and horses did in Afro-Eurasia). Although llamas could haul heavy loads, they were uncooperative and only partially domesticated, and thus mainly useful only for their fur, which was used for clothing.

Nonetheless, the domestication of plants and animals in the Americas, as well as the presence of villages and clans, suggests significant diversification and refinement of technique. At the same time, the centers of such activity were many, scattered, and more isolated than those in Afro-Eurasia—and thus more narrowly adapted to local geographical climatic conditions, with little exchange between communities. This fragmentation in migration and communication was a distinguishing force in the gradual pace of change in the Americas, and it contributed to their taking a path of development separate from Afro-Eurasia’s.

Europe: Borrowing Agricultural Ideas

In some places, agricultural revolutions occurred through the borrowing of ideas from neighboring regions, rather than through innovation. Peoples living at the western fringe of Afro-Eurasia, in Europe, learned the techniques of settled agriculture through contact with other regions.

By 7000 BCE, people in regions of Europe close to the societies of Southwest Asia, such as those living in what are modern-day Greece and the Balkans, abandoned their hunting and gathering lifeways to become settled agriculturists. (See Map 1.8.) Places like the Franchthi Cave, in Greece, reveal that around 6000 BCE the inhabitants borrowed innovations from their neighbors in Southwest Asia, such as methods for herding domesticated animals and planting wheat and barley. From the Aegean and Greece, settled agriculture and domesticated animals expanded westward throughout Europe, accompanied by the development of settled communities.

The emergence of agriculture and village life occurred in Europe along two separate paths. The first and most rapid trajectory followed the northern rim of the Mediterranean Sea. Domestication of crops and animals moved westward, following the prevailing currents of the Mediterranean, from what is now Turkey through the islands of the Aegean Sea to mainland Greece, and from there to southern and central Italy and Sicily. Once the basic elements of domestication had arrived in the Mediterranean region, the speed and ease of seaborne communications aided astonishingly rapid changes. Almost overnight, hunting and gathering gave way to domesticated agriculture and herding.

The second trajectory took an overland route: from Anatolia, across northern Greece into the Balkans, then northwestward along the Danube River into the Hungarian plain, and from there farther north and west into the Rhine River valley in modern-day Germany. Change here likely resulted from the transmission of ideas rather than from population migrations, for community after community adopted domesticated plants and animals and the new mode of life. This route of agricultural development was slower than the Mediterranean route for two reasons. First, domesticated crops, or individuals who knew about them, had to travel by land, as there were few large rivers like the Danube. Second, it was necessary to find new groups of domesticated plants and animals that could flourish in the colder and more forested lands of central Europe. Agriculturalists here had to plant their crops in the spring and harvest in the autumn, rather than the other way around. Cattle rather than sheep became the dominant herd animals.

In Europe, the main cereal crops were wheat and barley, and the main herd animals were sheep, goats, and cattle—all of which had been domesticated in Southwest Asia. (Residents domesticated additional plants, such as olives, later.) These fundamental changes did not bring dramatic material progress, however. The typical settlement in Europe at this time consisted of a few dozen mud huts. These settlements, although few, often comprised large “long houses” built of timber and mud, designed to store produce and to shelter animals during the long winters. Some settlements had sixty to seventy huts—in rare cases, up to a hundred. Hunting, gathering, and fishing still supplemented the new settled agriculture and the herding of domesticated animals. The innovators were dynamic in blending the new ways with the old. Consider that around 6000 BCE, hunters and gatherers in southern France adopted the herding of domesticated sheep, but not the planting of domesticated crops—that would have conflicted with their preference for a life of hunting, which was a traditional part of their economy.

By about 5000–4000 BCE, communities living in areas around rivers and in the large plains had embraced the new food-producing economy. Elsewhere (notably in the rugged mountain lands that still predominate in Europe’s landscape), hunting and foraging remained humans’ primary way of subsisting. Thus, across Afro-Eurasia, humans changed and were changed by their environments. While hunting and gathering remained firmly entrenched as a way of life, certain areas with favorable climates and plants and animals that could be domesticated began to establish settled agricultural communities, which were able to support larger populations than hunting and gathering could sustain.

More information

Map 1.8 is titled, “The Spread of Farming in Europe.” The map shows how farming communities spread across Europe between 7000 and 4500 B C E, as well the location of early farming communities, regions of dense hunter-gatherer settlements to 4500 B C E, and the two routes of agricultural diffusion through Europe, continental and coastal. Sections of the map show the spread of farming communities through Southeastern Europe, including Greece, Bulgaria, and Romania (7000-5500 B C E); Mediterranean Europe, including the Adriatic coast, Italy and the southern coasts of France and Spain (7000-4500 B C E); and Central Europe, including Germany, Poland, and northern France (5500-4500 B C E). Early farming communities are concentrated throughout these three areas, while regions of dense hunter-gatherer settlements appear on the northern coasts of Spain and France, southern England (connected to France via a land bridge), the Scandinavian coasts that touch the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, as well as the banks of the Dneiper River. The coastal route of agricultural diffusion moves west from Cyprus and Turkey along the Greek coast, to and around Sicily, north along the Italian coast, and then west and south along the coasts of France and Spain. The continental route of agricultural diffusion moves west from Turkey into Greece and the Balkans, then northwest along the Danube into the Hungarian plain, and from there into the Rhine River valley and then France along the Seine and Loire Rivers.

MAP 1.8 | The Spread of Farming in Europe

The spread of agricultural production into Europe after 7000 BCE represents geographic diffusion. Europeans borrowed agricultural techniques and technology from other groups, adapting those innovations to their own situations.

- Trace the two pathways by which agriculture spread across Europe. What shaped the routes by which agriculture diffused?

- How might scholars know that there were two routes of diffusion, and why would the existence of different diffusion routes matter?

- Identify the locations of the early farming communities. What geographical features seem to have influenced where these farming communities sprang up?

The Environmental Impact of the Agricultural Revolution and Herding

From the moment humans began to farm and herd on a large scale, they began to have a warming effect on the climate. The burning of forests, the cultivation of the major grain crops, and the amassing of large herds of domesticated animals caused methane and carbon dioxide (today called greenhouse gases) to escape from the earth and be trapped in the earth’s atmosphere. As a result, cooling cycles that occurred as the earth tilted away from the sun were not as severe as they would have been. Of course, it was only in the last 200 years that these gases have caused the severe warming of the planet that threatens our planet’s existence.