The Islamic World in a Time of Political Fragmentation

While the number of Muslim traders began to increase in commercial hubs from the Mediterranean to the South China Sea, it was not until the ninth and tenth centuries CE that Muslims became a majority within their own Abbasid Empire (see Chapter 9), and even then rulers struggled to unite the culturally diverse Islamic world. From the outset, Muslim rulers and clerics dealt with large non-Muslim populations, even as some in these groups were converting to Islam. Rulers accorded non-Muslims religious toleration as long as the non-Muslims accepted Islam’s political dominion. Jewish, Christian, and Zoroastrian communities within Muslim lands were free to choose their own religious leaders and to settle internal disputes in their own religious courts. They did, however, have to pay a special tax, the jizya, and defer to their Muslim rulers’ political decisions. While tolerant, Islam was an expansionist, universalizing faith. Intense proselytizing—especially by Sufi missionaries (whose ideas are discussed later in the chapter)—carried the sacred word to new frontiers and, in the process, reinforced the spread of Islamic institutions that supported commercial and cultural exchange.

Environmental Challenges and Political Divisions

Severe environmental conditions—freezing temperatures and lack of rainfall—afflicted the eastern Mediterranean and the Islamic lands of Mesopotamia, the Iranian plateau, and the steppe region of central Asia in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. The Nile’s low water levels devastated Egypt, the breadbasket for much of the area. No less than one-quarter of the summer floods that normally brought sediment-enriching deposits to Egypt’s soils and guaranteed abundant harvests failed in this period. Driven in part by drought, Turkish nomadic pastoralists poured out of the steppe lands of central Asia in search of better lands, wreaking political and economic havoc everywhere they invaded.

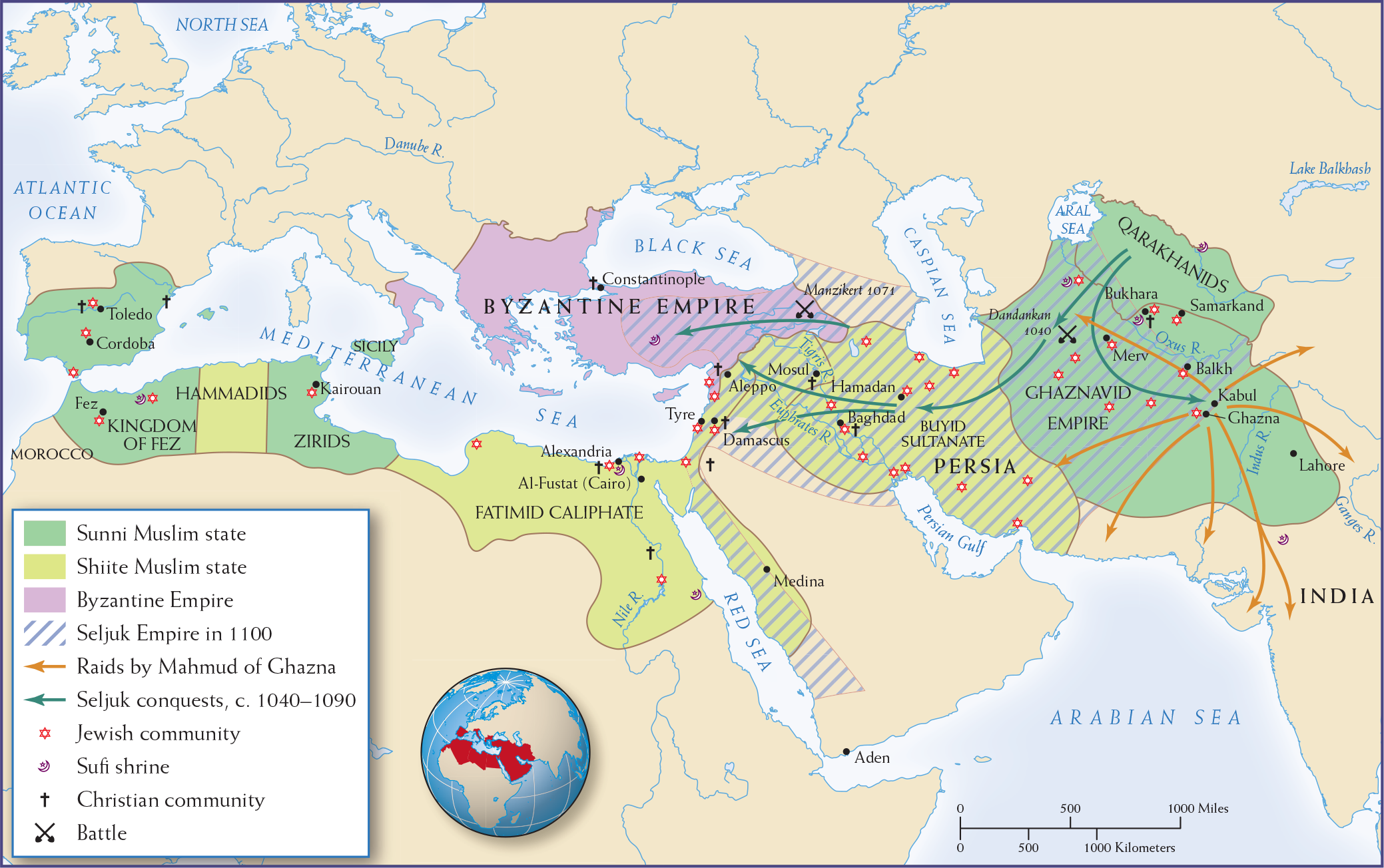

At the same time that climate-driven Turkish pastoralists were migrating in search of better lands and the Islamic faith was spreading across Afro-Eurasia, the political institutions of Islam were fragmenting. (See Map 10.2.) From 950 to 1050 CE, it appeared that Shiism would be the vehicle for uniting the Islamic world. The Fatimid Shiites had established their authority over Egypt and much of North Africa (see Chapter 9), and the Abbasid state in Baghdad was controlled by a Shiite family, the Buyids. Each group created universities, in Cairo and Baghdad respectively, ensuring that leading centers of higher learning were Shiite. But divisions also sapped Shiism, and Sunni Muslims began to challenge Shiite power and establish their own strongholds. In Baghdad, the Shiite Buyid family surrendered to the invading Seljuk Turks, a Sunni group, in 1055. A century later, the last of the Shiite Fatimid rulers gave way to a new Sunni regime in Egypt.

The Seljuk Turks who took Baghdad had been migrating into the Islamic heartland from the Asian steppes as early as the eighth century CE, bringing with them superior military skills and an intense devotion to Sunni Islam. When they flooded into the Iranian plateau in 1029, they contributed to the end of the magnificent cultural flourishing of the early eleventh century. When Seljuk warriors ultimately took Baghdad in 1055, they established a nomadic state in Mesopotamia in place of the once powerful Abbasid state that now lacked the resources to defend its lands and its peoples, weakened by famines and pestilence. The Seljuk invaders destroyed institutions of learning and public libraries and looted the region’s antiquities. Once established in Baghdad, they founded outposts in Syria and Palestine, then moved into Anatolia after defeating Byzantine forces in 1071.

The Spread of Sufism

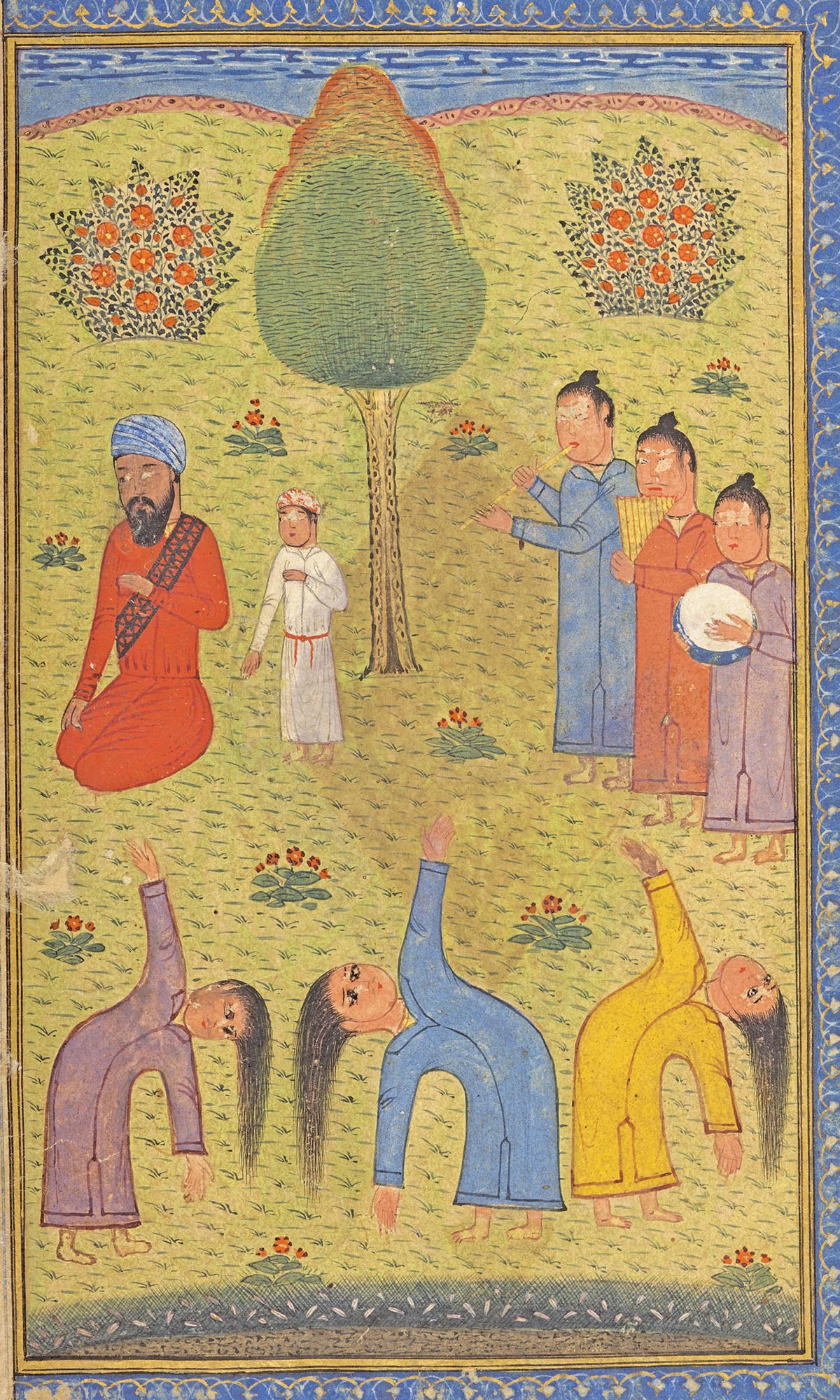

Even in the face of political splintering, Islam’s spread was facilitated by a popular, highly mystical, and communal form of the religion, called Sufism. The term Sufi comes from the Arabic word for wool (suf), which many of the early mystics wrapped themselves in to mark their penitence. Seeking closer union with God, Sufis performed ecstatic rituals, such as repeating over and over again the name of God. In time, groups of devotees gathered to read aloud the Quran and other religious tracts. Sufi mystics’ desire to experience God’s love found ready expression in poetry. Most admired of Islam’s mystic poets was Jalal al-Din Rumi (1207–1273), spiritual founder of the Mevlevi Sufi order that became famous for the ceremonial dancing of its whirling devotees, known as dervishes.

More information

Map 10.2 is titled The Islamic World, 900-1200 C E. The map of southern Europe, northern Africa, and western Asia shows the regions in which the Sunni Muslim state, the Shiite Muslim state, the Byzantine Empire, and the Seljuk Empire existed. It also shows the path of raids by Mahamud of Ghazna and Seljuk conquests, as well as the locations of Jewish communities, Sufi shrines, Christian communities, and notable battles. The Sunni Muslim state covers much of modern day Portugal and Spain, as well as sections of the northern parts of modern day Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. It also extends to all of Sicily. There is another large section of the Sunni Muslime state that stretched from the eastern border of the Shiite Muslim all the way north into modern day Kazakhstan and south west into modern day India. The Kingdom of Fez is located in modern day Morocco and Algeria, and Zirids is primarily located in modern day Tunisia. The Chaznavid Empire and Qarakhanids are located in the region of the Sunni Muslim state in west Asia. There are sixteen Jewish communities and three Christian communities scattered throughout the Sunni Muslim state. There are four Sufi shrines scattered throughout the region and one battle in the Chaznavid Empire. A section of the center Sunni Muslim state in northern Africa is missing and belongs to the Shiite Muslim state. It is labeled as Hammadis. The Shiite Muslim state covers much of modern day Libya, Egypt, the western coast of the Arabian peninsula, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. The portion in northern Africa is labeled Fatimid Caliphate and the section primarily located in modern day Iraq and Iran is labeled Persia and Buyid Sultanate. There are 22 Jewish communities and 7 Christian communities scattered throughout the Shiite Muslim state. There is a Sufi shrine marked near Cairo in modern day Egypt. The Byzantine Empire stretches from modern day southern Italy, through much of southeastern Europe, all the way through modern day Turkey. There is one Jewish community and two Christian communities scattered throught the empire. There is one Sufi shrine near the center of the empire and one battle near the eastern border. The Seljuk Empire in 1100 extends from the eastern part of the Byzantine Empire, down to the western coast of the Arabian peninsula, and east through most of the Shiite Muslim state and the section of the Sunni Muslim state in west Asia. Seven line with arrows representing raids by Mahud of Ghazna radiate from the eastern section of the Sunni Muslim state out in all directions, stretching to the border of Persia in the west, further into India to the south, and into the edge of China to the east. Six arrows representing Seljuk conquests circa 1040 to 1090 stretch from Qarakhanids in the northeaster region of the Sunni muslim state further into the state in the east and down through the Shiite Muslim state to the west, the furthest arrow stretching into the Byzantine Empire.

MAP 10.2 | The Islamic World, 900–1200 CE

The Islamic world experienced political fragmentation in the first centuries of the second millennium.

- According to the map key, what were the two major types of Islamic states in this period? What were some of the major political entities?

- What were the sources of instability in this period according to the map?

- What do you note about the locations of Jewish and Christian communities, as well as Sufi shrines, across the Islamic world?

Although many ulama (scholars) despised the Sufis and loathed their seeming lack of theological rigor, the movement spread with astonishing speed and offered a unifying force within Islam. Sufism’s emotional content and strong social bonds, sustained in Sufi brotherhoods, added to its appeal for many. Sufi missionaries from these brotherhoods carried the universalizing faith to India, to Southeast Asia, across the Sahara Desert, and to other distant locations. It was through these brotherhoods that Islam became truly a religion of the people. As trade increased and more converts appeared in the Islamic lands, urban and peasant populations came to understand the faith practiced by the political, commercial, and scholarly upper classes even while they remained attached to the ways of their Sufi brotherhood. Islam became even more accommodating over time, embracing Persian literature, Turkish ruling skills, and Arabic-language contributions in law, religion, literature, and science.

Expanding the Islamic World

Buoyed by Arab dhows on the high seas and carried on the backs of camels following commercial networks, Islam had been transformed from Muhammad’s original goal of creating a religion for Arab peoples (see Chapter 9). By 1300, its influence spanned Afro-Eurasia and it enjoyed multitudes of non-Arab converts. It attracted urbanites and rural peasants alike, as well as its original audience of desert nomads. Its extraordinary universal appeal generated an intense Islamic cultural flowering around 1000 CE.

Some people worried about the preservation of Islam’s true nature, as Arabic ceased to be the language of many Muslims. It is true that the devout continued to read and recite the Quran in its original tongue, as the religion mandated. But Persian was now the language of Islamic philosophy and art, and Turkish was the language of law and administration. Moreover, Jerusalem and Baghdad no longer stood alone as Islamic cultural capitals. Other cities, housing universities and other centers of learning, promoted alternative versions of Islam. In fact, some of the most dynamic thought came from Islam’s geographical peripheries.

At the same time, cultural diversity fostered blossoming in all fields of high learning. Indicative of the prominence of the Islamic faith and the Arabic language in thought was the legendary Ibn Rushd (1126–1198). Known as Averroës in the west, where scholars pored over his writings, he wrestled with the same theological issues that troubled western scholars. Steeped in the writings of Aristotle, Ibn Rushd became Islam’s most thoroughgoing advocate for the use of reason to understand the universe. His knowledge of Aristotle was so great that it influenced the thinking of the Christian world’s leading philosopher and theologian, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274). Most importantly, Ibn Rushd believed that faith and reason could be compatible. He also argued for a social hierarchy in which learned men would command influence akin to Confucian scholars in China or Greek philosophers in Athens. Ibn Rushd believed that the proper forms of reasoning had to be entrusted to the educated class—in the case of Islam, the ulama—who would then serve the common people.

Equally powerful works appeared in Persian, which by now was expressing the most sophisticated ideas of culture and religion. Best representing the new Persian ethnic pride was Abu al-Qasim Firdawsi (920–1020 CE), a devout Muslim who believed in the importance of pre-Islamic Sasanian traditions. In the epic poem Shah Namah, or The Book of Kings, he celebrated the origins of Persian culture and narrated the history of the Iranian highland peoples from the dawn of time to the Muslim conquest. As part of his effort to extol a pure Persian culture, Firdawsi attempted to compose his entire poem in Persian, unblemished by other languages and even avoiding Arabic words.

The Islamic world’s achievements in science were truly remarkable. Its scholars were at the pinnacle of scientific knowledge throughout Afro-Eurasia in this era. The study of the Quran, Islamic law, traditions of the Prophet (hadith), theology, poetry, and the Arabic language held primacy among the learned classes. Even so, Ibn al-Shatir (1304–1375), working on his own in Damascus, produced non-Ptolemaic models of the universe that later researchers noted were mathematically equivalent to those of Copernicus. Even earlier, the Maragha school of astronomers (1259 and later) in western Iran had produced a non-Ptolemaic model of the planets. Some historians of science believe that Copernicus must have seen an Arabic manuscript written by a thirteenth-century Persian astronomer that contained a table of the movements of the planets. In addition, scholars in the Islamic world produced works in medicine, optics, and mathematics as well as astronomy that were more advanced than the achievements of Greek and Roman scholars.

More information

An illustration depicts three dancers with one hand stretching towards the sky and the other reaching toward the earth. They have colorful robes and long hair. Three people play musical instruments to the side. A man and a child watch the dancers. There is a tree behind the people and flowers scattered throughout the illustration.

By the fourteenth century, Islam had achieved what early converts would have considered unthinkable. No longer a religion of a minority of peoples living among Christian, Zoroastrian, and Jewish communities, Islam had become the people’s faith. The agents of conversion were mainly Sufi saints and Sufi brotherhoods—not the ulama, whose exhortations had little impact on common people. The Sufis had carried their faith far and wide to North African Berbers, to Anatolian villagers, and to West African animists who believed that things in nature have souls. Ibn Rushd worried about the growing appeal of what he considered an “irrational” piety. But his message failed, because he did not appreciate that Islam’s expansionist powers rested on its appeal to common folk. While the sharia was the core of Islam for the educated and scholarly classes, Sufism spoke to ordinary men and women.

During this period, the Islamic world became one of the four cultural spheres that would play a major role in world history, laying the foundation for what would become known as the Middle East. Islam became the majority religion of most of the inhabitants of Southwest Asia and North Africa, Arabic language use became widespread, and the Turks began to establish themselves as a dominant force, ultimately creating the Ottoman Empire, which would last into the twentieth century. The Islamic world thus became integral in transregional trade and in the creation and transmission of knowledge.