Song China: Insiders versus Outsiders

The preeminent world power in 1000 CE was still China, despite its recent turmoil. In 907 CE, the Tang dynasty splintered into regional kingdoms, mostly led by military generals. In 960 CE one of these generals, Zhao Kuangyin, ended the fragmentation, reunified China, and assumed the mandate of heaven for the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE). The following three centuries witnessed many economic and political successes, but northern nomadic tribes kept the Song dynasty from completely securing its reign. (See Map 10.4 and Map 10.5.) Ultimately, one of those nomadic groups, the Mongols, would bring the Song dynasty to an end, but not until after Song influence had fanned out into Southeast Asia, helping to create new identities in the polities that developed there.

Economic Progress

Chinese merchants, like those from India and the Islamic world, participated in Afro-Eurasia’s powerful long-distance trade. Yet China’s commercial successes could not have occurred without the country’s strong agrarian base—especially its vast wheat, millet, and rice fields, which fed a population that reached 120 million. Crop cultivation benefited from breakthroughs in metalworking that produced stronger iron plows, which Song farmers harnessed to sturdy water buffalo to extend the agricultural frontier.

More information

Map 10.4 is titled East Asia in 1000 CE. The map shows the extent of Song China, as well as major trading centers, trade routes, and navigable rivers, as well as other trading centers, canals, peoples, and the wall between Korea and Khitan. Song China covers most of the area that present-day Eastern China controls today. The major trading centers are Hangzhou and Kaifeng. Other trading centers and trade routes dot the country. A canal extends from the eastern coast towards Kaifeng, while another moves north from that city. The Tangut people are in Xia to the Northwest, and the Khitan people are in Liao to the Northeast. The labeled major navigable rivers are the Yellow and the Yangzi.

MAP 10.4 | East Asia in 1000 CE

Several states emerged in East Asia between 1000 and 1300 CE, but none were as strong as the Song dynasty in China. Using the key to the map, try to identify the factors that contributed to the Song state’s economic dynamism.

- What do you note about the location of the major trading centers?

- What do you note about the distribution of the other trading centers?

- According to the map, what external factors kept the Song dynasty from completely securing its reign?

Manufacturing also flourished. With the use of piston-driven bellows to force air into furnaces, Song iron production in the eleventh century equaled that of Europe in the early eighteenth century. In the early tenth century CE, Chinese alchemists mixed saltpeter with sulfur and charcoal to produce a product that would burn and could be deployed on the battlefield: gunpowder. Song entrepreneurs were soon inventing a remarkable array of incendiary devices that flowed from their mastery of techniques for controlling explosions and high heat. At the same time, artisans were producing increasingly light, durable, and exquisitely beautiful porcelains. Chinese pottery had long been exported to the west (recall the tens of thousands of early ninth-century CE mass-produced Changsha pieces found in the Belitung shipwreck described earlier in this chapter), but Song pottery was much finer and more delicate. Before long, Song porcelain was the envy of all Afro-Eurasia (hence the modern term china for fine dishes). Also flowing from the artisans’ skillful hands were vast amounts of clothing and handicrafts, made from the fibers cultivated by Song farmers. In effect, the Song Chinese oversaw the world’s first manufacturing revolution, producing finished goods on a large scale for consumption far and wide.

More information

Map 10.5 is titled East Asia in 1200. The map shows the boundary of the original Song Empire, the area lost in 1126, and the names and locations of the Khitai people (in Western Liao) and the Tangut people (in Xia). The original Song Empire stretches south from the Gobi Desert and covers most of present-day Eastern China to the border with Vietnam. The northern section of this empire, including the Song capital of Kaifeng, is lost in 1126, while the Southern Song area, from Yangzhou down to Guangzhou, remains.

MAP 10.5 | East Asia in 1200

The Song dynasty regularly dealt with “barbarian” neighbors with a balance of military response and outright bribery.

- What were the major “barbarian” tribes on the borders of Song China during this period?

- Approximately what percentage of Song China was lost to the Jin in 1126?

- Apart from so-called barbarians, what other polities existed on the borders of Song China?

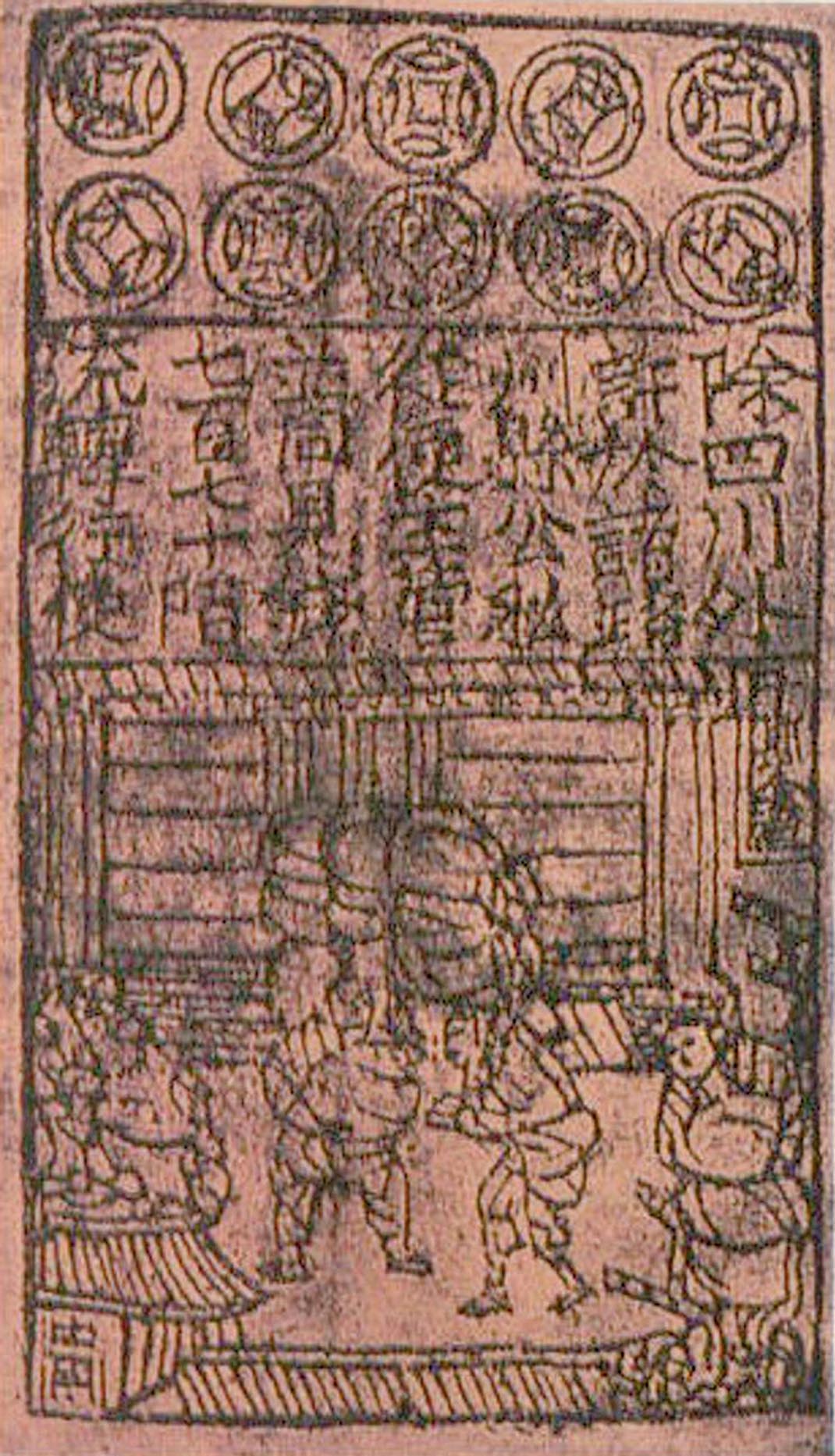

MONEY AND INFLATION Expanding commerce transformed the role of money and its wide circulation. By now the Song government was annually minting nearly 2 million strings of currency, each containing 1,000 copper coins. As the economy grew, the supply of metal currency could not match the demand, which fueled East Asia’s desire for gold from East Africa. At the same time, merchant guilds in northwestern Shanxi developed the first letters of exchange, called flying cash. These letters linked northern traders with their colleagues in the south. Before long, printed money became more common than minted coins for trading purposes. Even the government collected more than half its tax revenues in cash rather than grain and cloth. The government also issued more notes to pay its bills—a practice that ultimately contributed to runaway inflation.

More information

A woodblock printed bill shows two rows of coins, an inscription, and laborers at a warehouse.

New Elites

Song emperors built on Tang political institutions by expanding a central bureaucracy of scholar-officials chosen even more extensively through competitive civil service examinations. Zhao Kuangyin, or Emperor Taizu (r. 960–976 CE), himself administered the final test for all who had passed the highest-level palace examination. In subsequent dynasties, the emperor was the nation’s premier examiner, symbolically demanding oaths of allegiance from successful candidates. By 1100, these ranks of learned men had accumulated sufficient power to become China’s new ruling elite.

Expansion of the civil service examination system was crucial to a shift in power from the still-powerful hereditary aristocracy to a less wealthy but more highly schooled class of scholar-officials. Consider the career of the Northern Song reformer Wang Anshi (1021–1086), who ascended to power from a commoner family outside of Hangzhou in the east. He owed his success to gaining high marks in Song state examinations—a not insignificant achievement, for in nearby Fujian Province alone, of the roughly 18,000 candidates who gathered triennially to take the provincial examination, over 90 percent failed! After gaining the emperor’s ear, Wang eventually used his position to challenge the political and cultural influence of the old Tang dynasty elites from the northwest.

China’s Neighbors: Nomads, Japan, and Southeast Asia

China’s prosperity influenced its neighbors and its interactions with them. As the Song flourished, nomads on the outskirts closely eyed the Chinese successes. To the north, nomadic societies formed their own dynasties and adopted Chinese institutions. These non-Chinese nomads sought both to copy China proper and to conquer it.

Despite its sophisticated weapons, the Song army could not match its enemies on the steppe when the latter united against it. Steel tips improved the arrows that the Song soldiers shot from their crossbows, and flamethrowers and “crouching tiger catapults” sent incendiary bombs streaking into their enemies’ ranks. But none of these breakthroughs were unique. Warrior neighbors on the steppe mastered the new arts of war more fully than did the Song military.

As a result, China drew on its economic success (and the innovation of paper money) to “buy off” the borderlanders. For example, after losing North China to the Khitan Liao dynasty, the Song agreed to make annual payments of 100,000 ounces of silver and 200,000 bolts of silk. The treaty allowed them to live in relative peace for more than a century. Securing peace meant emptying the state coffers and then printing more paper money. This short-term solution, however, led to economic instability (particularly inflation) and military weakness, especially as the Song forces were cut off, via the steppe nomads, from their supply of horses for warfare purposes.

Feeling the pull of China’s economic and political gravity, cultures around China consolidated their own internal political authority and redefined their own identities in order to keep China from swallowing them up. At the same time, they increased their commercial transactions with China. In Japan, for instance, leaders distanced themselves from Chinese influences, but they also developed a strong sense of their islands’ distinctive identity. Even so, the long-standing dominance of Chinese ways remained apparent at virtually every level of Japanese society and was most pronounced at the imperial court in the capital city of Heian (present-day Kyoto), which was modeled after the Chinese capital city of Chang’an. Outside Kyoto, however, a less China-centered way of life existed and began to impose itself on the center. Here, local notables, mainly military leaders and large landowners, began to challenge the imperial court for dominance. This challenge was accompanied by the arrival of an important new social group in Japanese society—samurai warriors. By the beginning of the fourteenth century, Japan had multiple sources of political and cultural power: an imperial family with prestige but little authority; an endangered and declining aristocracy; powerful landowning notables based in the provinces; and a rising and increasingly ambitious class of samurai.

More information

An illustration depicts a battle with many warriors in full armor riding on horseback. Some of the warriors carry very long bows and some stand on foot.

During the Song period, Southeast Asia became a crossroads of Afro-Eurasian influences. The Malay Peninsula became home to many entrepôts for traders shuttling between India and China, because it connected the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea. (See Map 10.6.) Consequently, Southeast Asia was characterized by a fusion of religions and cultural influences: Vedic Brahmanism in Bali and other islands, Islam in Java and Sumatra, and Mahayana Buddhism in Vietnam and other parts of mainland Southeast Asia. Important Vedic and Buddhist kingdoms emerged in Southeast Asia. The most powerful and wealthy of these kingdoms was the Khmer Empire (889–1431 CE), with its capital at Angkor, in present-day Cambodia. Public works and magnificent temples dedicated to the revived Vedic gods from India went hand in hand with the earlier influence of Indian Buddhism. One of the greatest temple complexes in Angkor—Angkor Wat—exemplified the Khmers’ heavy borrowing from Vedic Indian architecture and the revival of the Hindu pantheon within the Khmer royal state. Kingdoms like the Khmer Empire functioned as political buffers between the strong states of China and India and brought stability and further commercial prosperity to the region.

More information

A bird’s eye view of Angkor Wat. Angkor Wat has a central building that has five symmetrically built towers. Surrounding the central towers are rectangular-shaped walls. Beyond these walls is a courtyard. An outer rectangular wall stands at the edge of the courtyard and encompasses the entire complex. Many trees surround Angkor Wat, two ponds sit next to it, and a larger body of water is visible behind it.

More information

Map 10.6 is titled Southeast Asia, 1000-1300 C E. The map shows the Angkor Empire, Srivijaya Empire, and Pagan Kingdom, as well as trade routes and Siam and Khmer peoples. The Srivijaya Empire in 1100 controls Sumatra Island and the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. The Angkor Empire in 1210 controls present-day Vietnam and Cambodia (where the Khmer and Siam people are located) and the northern portion of the Malay Peninsula. The Pagan Kingdom in 1100 controls the area west of the Angkor Empire and goes north towards but not reaching the city of Dali. Trade routes travel across India, Tibet, and China to Bali and Borneo.

MAP 10.6 | Southeast Asia, 1000–1300 CE

Cross-cultural influences affected Southeast Asian societies during this period.

- What geographic features (rivers, mountains, islands, straits, etc.) shape Southeast Asia?

- What makes Southeast Asia unique geographically compared to other regions of the world?

- Based on the map, why were the kingdoms of Southeast Asia exposed to so many cross-cultural influences?

Expanding China

Paradoxically, the increasing exchange between outsiders and insiders within China hardened the lines that divided them and gave residents of China’s interior a highly developed sense of themselves as a distinctive people possessing a superior culture. Exchanges with outsiders nurtured a “Chinese” identity among those who considered themselves true insiders and referred to themselves as Han. Song Chinese grew increasingly suspicious and resentful toward the outsiders living in their midst. They called these outsiders “barbarians” and treated them accordingly.

More information

A sketch of a Chinese person talking with a barbarian. Three barbarians are bowing down to the Chinese person. The barbarian in the front, who is the only one wearing armor, is holding out his hand to the Chinese man.

Print culture crystallized the distinct Chinese identity. Of all Afro-Eurasian societies in 1300, the Chinese were the most advanced in their use of printing, book publishing, and circulation, a result of the invention of a movable type printing press by the artisan Bi Sheng around 1040. Song dynasty printed books established classical Chinese as the common language of educated classes in East Asia. The Song government used its plentiful supply of paper to print books, especially medical texts, and to distribute calendars. The private publishing industry expanded, and printing houses throughout the country produced Confucian classics, works on history, philosophical treatises, and literature—all of which figured in the civil examinations. Buddhist publications, too, were available everywhere.

In many respects, the Song period represented China’s greatest age. China’s resources, its huge population base coupled with a strong agrarian economy, and its strong foreign trade and diplomatic relations made China the wealthiest of the four major cultural spheres. And its common language and Confucian civil service system, which enabled a transfer of power from hereditary aristocrats to Confucian scholars, made it the most unified. As a result, China’s influence on the surrounding region was tremendous.

Glossary

- flying cash

- Letters of exchange—early predecessors of paper money—first developed by guilds in the northern Song province Shanxi that eclipsed coins by the thirteenth century.