Christian Europe

Europe from 1000 to 1300 CE was a continent of strong contrasts. Intensely localized power was balanced by a shared sense of Europe’s place in the world, especially with respect to Christian identity. Some inhabitants even began to believe in the existence of something called “Europe” and increasingly referred to themselves as “Europeans” (see Map 10.7), especially in contrast to the world of Islam to the east and south.

More information

An photo of part of the Bayeux Tapestry shows several figures engaged in battle. Three figures stand with armor and shields at the center. One body is laying on the ground next to them and several bodies are laying on the ground below them. There are armored warriors on horseback on both sides of the foot soldiers. One of the warriors on horseback is slouched over the neck of the horse and holds a sword while the horse tramples another warrior underfoot. Spears fly through the air and there is writing hovering above the figures.

More information

Map 10.7 is titled Western Christendom in 1300. The map shows four major areas of western Christendom as well as the direction of expansions, cities with over 50,000 population, important cities under 50,000, and universities with the dates of their founding. The first expansion is the spread of western Christianity into Eastern Europe and Baltic regions through conquest and migration. This spread goes from central Europe through the Polish States and toward the Russian Principalities. The second is the spread of western Christianity through the Spanish Reconquista. This occurs on the Iberian Peninsula in present-day Spain. The third is the spread of western Christianity through the Norman Conquest of Sicily. The fourth is the spread of western Christianity through the Crusades. The Crusades go from present-day Italy to the Crusader states. The Crusader states consist of present-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and part of Turkey. Cities with a population of over 50,000 include Constantinople, Palmero, Florence, Milan, Genoa, Barcelona, Granada, Paris, Rouen, Bruges, and London. Other important cities with less than 50,000 people include Novgorod, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Kiev, and Ghent. Universities date back to as early as the 9th century and include Oxford, Cambridge, Paris and Orleans, Seville and Lisbon, Bologna and Rome, Prague, Baghdad, and Cairo.

MAP 10.7 | European Christendom in 1300

Catholic Europe expanded geographically and integrated culturally during this era.

- According to this map, into what areas did western Christendom successfully expand?

- What were the different means by which western Christianity expanded?

- Which are the earliest universities on the map? What might account for the flourishing of universities where they were located?

Western and Northern Europe

The collapse of Charlemagne’s empire had exposed much of northern Europe to invasion, principally from the Vikings, and left the peasantry there with no central authority to protect themselves from local warlords. Armed with deadly weapons, these strongmen collected taxes, imposed forced labor, and became the unchallenged rulers of society. Peasants toiled under the authority of these landholding lords, who controlled every detail of their subjects’ lives. The Franks (in northern France) were the trendsetters for this development in eleventh- and twelfth-century Europe.

The peasantry’s subjugation to this warlord or knightly class was at the heart of a system scholars have called feudalism (emphasizing the power of the local lords over the peasantry), but a more accurate term for the system is manorialism, which emphasizes instead the manor’s role as the basic unit of economic power. The manor comprised the lord’s fortified home (or castle), the surrounding fields controlled by the lord but worked by peasants (as free tenants or as serfs tied to the land), and the village where those peasants lived. Although manorialism was driven by agriculture, limited manufacturing and trade augmented the manor economy. Assured of control of the peasantry, feudal lords watched over an agrarian breakthrough—which fueled a commercial transformation that drew Europe into the rest of the global trading networks. Lordly protection and more advanced metal tools like axes and plows, combined with heavier livestock to pull plows through the root-infested sods of northern Europe, led to massive deforestation. This system harnessed agrarian energy and helped western Europe leap forward and shed its identity as a somewhat “barbarian” appendage of the Mediterranean; it also had unforeseen environmental impacts that resulted from the deforestation.

More information

A view of Turku Castle. There is a taller section comprised of four towers surrounded by shorter buildings, including one circular section of the building in the lower left corner. The castle is surrounded by trees and there is a harbor visible in the background.

East-Central Europe

Nowhere did pioneering peasants develop more land than in the wide-open spaces of east-central Europe, the continent’s land of opportunity. Between 1100 and 1200, some 200,000 farmers emigrated from Flanders (in modern western Belgium), Holland, and northern Germany to eastern frontiers. Well-watered landscapes covered with vast forests filled up what are now Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and the Baltic states. These “Little Europes,” whose castles, churches, and towns echoed the landscape of France, now replaced economies that had been based on gathering honey, hunting, and the slave trade. For 1,000 miles along the Baltic Sea, forest clearings dotted with new farmsteads and small towns edged inward from the coast up the river valleys.

The social structure here was a marriage of convenience between migrating peasants and local elites. The area offered the promise of freedom from the arbitrary justice and the imposition of forced labor. Even the harsh landscape of the eastern Baltic (where the sea froze every year and impenetrable forests blocked settlers from the coast) was preferable to life in the west. For their part, the elites of eastern Europe—the nobility of Poland, Bohemia, and Hungary and the princes of the Baltic—wished to live well. But they could do so only if they attracted workers to their lands by offering newcomers a liberty that did not exist in the west.

More information

An exterior view of Saint Sophia Cathedral. Several domes with pointed tops extend from the top of the cathedral and the windows in front are arched at the top. Barren trees are planted near the cathedral and snow dusts the ground in front of it.

The East Slavic Lands

In the East Slavic lands, western settlers and knights met an eastern brand of Christian devotion. This world looked toward Byzantium, not Rome or western Europe. These lands were a giant borderland between the steppes of Eurasia and the booming centers of Europe. Their cities lay at the crossroads of overland trade and migration, and Kyiv became one of the region’s greatest cities. Standing on a bluff above the Dnipro River, it straddled newly opened trade routes. With a population exceeding 20,000, including merchants from eastern and western Europe, Southwest Asia, South Asia, Egypt, and North Africa, Kyiv was larger than Paris—larger even than the much-diminished city of Rome.

Kyiv looked south to the Black Sea and to Constantinople. Christianity arrived in 988 CE, and under Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054), Kyiv became a small-scale Constantinople on the Dnipro. A stone church called Saint Sophia stood beside the imperial palace (as in Constantinople). With its distinctive “Byzantine” domes, it was a miniature Hagia Sophia (see Chapter 8). Its highest dome towered 100 feet above the floor, and its splendid mosaics depicting Byzantine saints echoed the religious art of Constantinople. The embrace of Orthodoxy spread throughout the East Slavic lands, from the elites to the peasants, although paganism did remain active until the early fifteenth century.

Due to the influence of the Orthodox form of Christianity, Byzantine-style churches were erected all along the great rivers leading to the trading cities of the north and northeast. These were not agrarian centers, but hubs of expanding long-distance trade. Each city became a small-scale Kyiv and a smaller-scale echo of Constantinople. The Orthodox religion thus looked to Byzantium’s Hagia Sophia rather than Roman Catholicism and the popes. Orthodox Christianity, however, remained the Christianity of a borderland—vivid oases of high culture that were set against the backdrop of vast forests and widely scattered settlements. Like the agricultural manors of western Europe, this region’s cities demonstrated the highly localized nature of power in Europe during this period.

Expanding Christian Europe

Christianity in this era—primarily the Roman Catholicism of the west, but also the Orthodoxy of the east—was a universalizing faith that transformed the territory that was becoming known as “Europe.” The Christianity of post-Roman Europe had been a religion of monks, and its most dynamic centers were great monasteries. Members of the laity were expected to revere and support their monks, nuns, and clergy, but not to imitate them. By 1200, all this had changed. The internal colonization of western Europe—the clearing of woods and founding of villages—ensured that parish churches arose in all but the wildest landscapes. Now the clergy reached more deeply into the private lives of the laity. Marriage and divorce, previously considered family matters, became the domain of the church.

More information

A fresco depicts Saint Francis renouncing his Father’s goods and earthly wealth. Saint Francis wears a piece of cloth around his waist, clasps his hands together in front of him, and has a circle behind his head as he looks to the sky. Men dressed as members of the clergy and monks surround him. Two children watch from the crowd. Two tall buildings are visible in the background. A decorative border surrounds the fresco.

New understandings of religious devotion and innovative institutions for learning developed in the west. For instance, the followers of Francis of Assisi (1182–1226) emerged as an order of preachers who brought a message of repentance. Franciscans encouraged the laity—from the poorest to the elite—to feel remorse for their wrongdoings, to confess their sins to local priests, and to strive to be better Christians. At nearly the same time, intellectuals were beginning to gather in Paris to form one of the first European universities, a sort of trade guild of scholars. These professional thinkers endeavored to prove that Christianity was the only religion that fully addressed the concerns of all rational human beings. Such was the message of Thomas Aquinas, who wrote Summa contra Gentiles (Summary of Christian Belief against Non-Christians) in 1264. The growing number of churches, new religious orders, and universities began to change what it meant to live in a “Christian Europe.”

Christian Europe’s Relations with the Islamic World

By the tenth and eleventh centuries CE, western Christianity was on the move, spreading into Scandinavia, southern Italy, the Baltic, and eastern Europe. Its ambitions to reconquer Spain and Portugal (which had been under Muslim control since the eighth century CE) demonstrated one of the effects of feudal power: the lords’ self-confidence, their belief in their military capability, and their pious sense of destiny were all inflated. Besides, the wealth of the east was irresistible to those whose piety entwined with an appetite for plunder. Yet the two Christendoms formed an uneasy alliance to roll back the expanding frontiers of Islam. Europeans zealously took war outside their own borders.

CRUSADES In the late eleventh century, western Europeans launched a wave of attacks against the Islamic world known as the Crusades. The First Crusade began in 1095, when Pope Urban II appealed to the warrior nobility of France to put their violence to good use: they should combine their role as pilgrims to Jerusalem with that of soldiers and free Jerusalem from Muslim rule. Such a “just war,” the clergy proposed, was a means for absolution, not a source of sin.

Starting in 1097, an armed host of around 60,000 men moved all the way from northwestern Europe to Jerusalem. The crusading forces included knights in heavy armor as well as people drawn from Europe’s impoverished masses, who joined the movement to help besiege cities and construct a network of castles as the Christian knights drove their frontier forward. The fleets of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa helped transport later Crusaders and supplied the kingdoms they created as they moved eastward. Later Crusaders, especially those from the upper class, brought their wives, who found a degree of autonomy away from their homelands and thus their prescribed gender roles. Eleanor of Aquitaine, for example, led her own army. Melisende (r. 1131–1152), born Armenian royalty in the Crusader state of Edessa, ruled as queen of Jerusalem after her father’s death, despite occasional attempts by her husband and later her son to challenge her authority. Regarded as wise and experienced in affairs of the state, she was popular with local Christians. As a result, the society of the Crusader states remained more open to women and the lower classes than societies back in Europe. There are even accounts of a children’s crusade (1212), inspired by the visions of a boy. Over time, the Crusades brought together a range of peoples from varied walks of life in common purpose. That purpose was one of conflict.

No fewer than nine Crusades were fought in the two centuries that followed Urban II’s call, but none ultimately created lasting Christian kingdoms in the lands the Crusaders “reconquered.” Most knights returned home, their epic pilgrimages completed. The remaining fragile network of Crusader lordships barely threatened the Islamic heartland. The real prosperity and the capital cities of Muslim kingdoms lay inland, away from the coast—in Cairo, Damascus, and Baghdad. The assaults’ long-term effect was to harden Muslim feelings against the millions of Christians who had previously lived peacefully in Egypt and Syria.

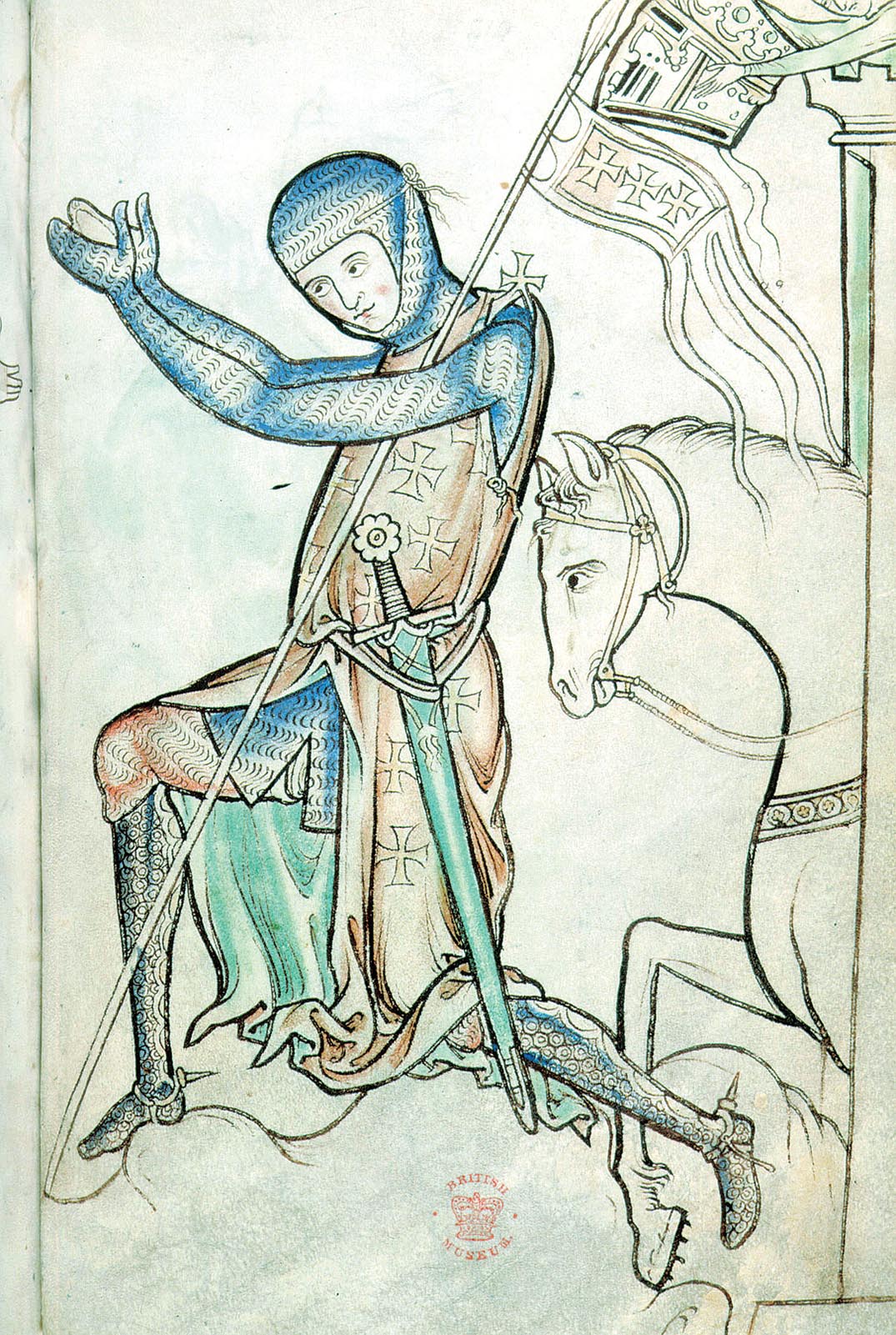

More information

A painting of a kneeling crusader. The crusader is in full armor with a sword at his side and a banner leaning against him. While kneeling he is holding his hands out with his palms up. A horse stands behind him.

Even so, a range of sources offer Muslim and Christian perspectives that show tolerance of, and curiosity about, each other. For example, Usāmah Ibn Munqidh (1095–1188), a learned Syrian leader, described his shock at the European Crusaders’ backward medical practices and the freedom they offered their wives, in addition to well-meaning exchanges such as a particular Christian’s confusion about the direction in which Muslims pray. Similarly, Jean de Joinville (1224–1317), a French chronicler of Louis X of France who led the Seventh Crusade, marveled at the order within the sultan’s camp and the role of musicians in calling the Muslim forces to hear the sultan’s orders.

Other campaigns of Christian expansion, like the Iberian efforts to drive out the Muslims, were more successful. Beginning with the capture of Toledo in 1061, the Christian kings of northern Spain slowly pushed back the Muslims. Eventually they reached the heart of Andalusia in southern Iberia and conquered Seville, adding more than 100,000 square miles of territory to Christian Europe. Another force, from northern France, crossed Italy to conquer Muslim-held Sicily, ensuring Christian rule in that strategically located mid-Mediterranean island. Unlike the Crusaders’ fragile foothold at the edge of the Middle East, these two conquests were a turning point in relations between Christian and Muslim power in the Mediterranean. Christianity—in particular, the rise of the Roman Catholic Church, the spread of universities, and the fight against the Muslims in their native and spiritual homelands—was a force that helped create a cultural sphere known as Europe, whose peoples would become known as European, at the western end of the Afro-Eurasian landmass during this period.

Glossary

- manorialism

- System in which the manor (a lord’s home, its associated industry, and surrounding fields) served as the basic unit of economic power; an alternative to the concept of feudalism (the hierarchical relationships of king, lords, and peasantry) for thinking about the nature of power in western Europe from 1000 to 1300 CE.