Contact Between China and Rome

The Roman Empire (c. 300 BCE–c. 300 CE)

At the other end of Afro-Eurasia from Han China, in a centuries-long process, Rome became a great power that ruled over more than 60 million subjects. The Roman Empire at its height encompassed lands from the highlands of what is now Scotland in Europe to the lower reaches of the Nile River in modern-day Egypt and part of Sudan, and from the borders of the Inner Eurasian steppe in Ukraine and the Caucasus to the Atlantic shores of North Africa. (See Map 7.3.)

More information

A wall painting of men and women dining together. Many of them sit reclined while two figures stand in front of the seating area. The walls of the room the figures are in are decorated, with a mural of two large spotted cats on the wall behind the figures and geometric patterns on the ceiling.

Whereas the similarly sized Han Empire dominated an enormous and unbroken landmass, the Roman Empire dominated lands around the Mediterranean Sea. Like the Han Chinese, the Romans acquired command over their world basically through violent military expansion, with the attendant use of authority, persuasion, and “soft power.” By the first century CE, almost unceasing warfare against their neighbors had enabled the Romans to forge an unparalleled number of ethnic groups and minor states into a single, large political state. We can easily see how the Latin word that the Romans used to designate command over their subjects—imperium—became the source for the English words empire and imperialism.

The Global View

More information

Map 7.3 is titled, Roman Expansion to 120 C E. Regions on the map are shaded to illustrate a different period of expansion (to 201 B C E, 201-1000 B C E, 100-44 B C E, 44 B C E-14 CE, 14-96 CE, and 96-116 C E). The map also shows the Mediterranean sea current, Roman provinces, Border peoples, and Important provincial capitals. Expansion to 201 B C E includes modern Spain and Italy (the Roman provinces of Lusitania, Baetia, Tarraconensis, Sardinia, Sicilia, Corsica, and Italia). From 201-100 B C E, the area expands to include southern France (Gallia Narbonensis) and the Spanish Islands (Majorca and Minorca), north Africa around Carthage (Africa), Greece (Macedonia, Achaea), and western Turkey (Asia). From 100-44 B C E, expansion covers the rest of France (Galla Aquitania, Gallia Lugdunensis, Belgica, Germania Inferior, Germania Superior), more of North Africa (Numidia and Cyrenaica), parts of Turkey (Cicilia, Bithynia, and Pontus), Syria, and Cyprus. From 44 B C E-14 C E, Egypt (Aegyptus) and Judaea, as well as more of Turkey (Galatia, Lycia, and Pamphylia), and the Balkans (Moesia Superior and Inferior, Raetia, Noricum, Pannonia, Dalmatia). From 14-96 C E, expansion continues in North Africa (Mauretania Tingitania, Mauretania Caesariensis), part of Germany (Lauri and Decumates), England (Britannia), northern Greece (Thracia), and Turkey (Cappadocia). Finally, from 96-116 C E, expansion reaches Arabia, Mesopotamia, Armenia, and Dacia north of Moesia. Border peoples listed are Germani, Iazyges, Gothi, Scythi, Iberi, and Arabi. Important provincial capitals from west to east include Corduba, Londinium, Carthage, Rome, Syracuse, Corinth, Alexandria, Caesarea, Antioch, and Jerusalem. Arrows indicate the direction of Mediterranean Sea currents. The current rotates counterclockwise in three different sections of the Mediterranean Sea (moving east-west, they are from Cyrenaica to Achaea; from Carthage to Sicilia; and from Mauretania Tingitania to Baetia; before the current exits between modern day Spain and Morocco).

Foundations of the Roman Empire

The emergence of Rome as a world-dominating power was a surprise. Down to the 350s BCE, the Romans were just one of a number of Latin-speaking communities in Latium, a region in the center of the Italian Peninsula. Although Rome was one of the largest urban centers there, it was still only a city-state that had to ally with other towns for self-defense. However, Rome soon began an extraordinary phase of military and territorial expansion, and by 275 BCE it had taken control of most of the peninsula. Three major factors influenced the beginnings of Rome’s imperial expansion: migrations of foreign peoples, Rome’s own military might, and its political innovations.

POPULATION MOVEMENTS Between 450 and 250 BCE, migrations from northern and central Europe brought large numbers of Celts to settle in lands around the Mediterranean Sea. They convulsed the northern rim of the Mediterranean, staging armed forays into lands from what is now Spain in the west to present-day Turkey in the east. One of these migrations involved dozens of Gallic peoples from the region of the Alps and beyond in a series of violent incursions into northern Italy that ultimately led—around 390 BCE—to the seizure of Rome. The important result for the Romans was not their city’s capture, which was temporary yet traumatic, but rather the permanent dislocation that the invaders inflicted on the city-states of the Etruscans. The Etruscans, themselves likely a combination of indigenous people and migrants from Asia Minor centuries before, spoke their own language and were centered in what is now the region of Tuscany north of Rome. Before the Gallic invasions, the Etruscans had dominated much of the Italian Peninsula. While the Etruscans with great difficulty drove the invading Gauls back northward, their cities never fully recovered nor did their ability to dominate other peoples in Italy, including their fledgling rival, the city of Rome. The Gallic migrations had weakened Etruscan power, one of the most formidable roadblocks to Roman expansion in Italy.

MILITARY INSTITUTIONS AND THE WAR ETHOS The Romans achieved unassailable military power by organizing the communities that they conquered in Italy into a system that generated manpower for their army. This development began around 340 BCE, when the Romans faced a concerted attack by other Latin city-states. By then, the other Latins viewed Rome not as an ally in a system of mutual defense but as a growing threat to their own independence. After overcoming these nearby Latins, the Romans charged onward to defeat one community after another in Italy. Demanding from their defeated enemies a supply of men for the Roman army every year, Rome amassed a huge reservoir of military manpower.

In addition to their overwhelming advantage in manpower, the Romans cultivated an unusual war ethos. A heightened sense of honor drove Roman men to push themselves into battle again and again, and never to accept defeat. Roman soldiers were guided by the example of great warriors and shaped by a regime of training and discipline. Disobedience by a whole unit led to a savage mass punishment, called “decimation,” in which every tenth man was arbitrarily selected and executed. The Roman army trooped out to war in annual spring campaigns beginning in the month—still called March today—dedicated to and named for the Roman god of war, Mars.

By 275 BCE, Rome controlled the Italian Peninsula. It next entered into three great Punic Wars with Carthage, which had begun as a Phoenician colony and was now the major power centered in the northern parts of present-day Tunisia (see Chapters 4 and 5). The First Punic War (264–241 BCE) was a prolonged war finally settled by large-scale naval battles around the island of Sicily. With their victory, the Romans acquired a dominant position in the western Mediterranean. The Second Punic War (218–201 BCE), however, revealed the real strength and power of the Roman army. The Romans drew on their reserve force of nearly 750,000 men to ultimately repulse—although with huge casualties and dramatic losses—the Carthaginian general Hannibal’s invading force of 20,000 troops and war elephants. The Romans took the war to enemy soil, winning the decisive battle at Zama near Carthage in late 202 BCE. Despite their ultimate victory, Rome’s initial losses in the early years of the Second Punic War were so devastating that a law was passed limiting the wealth that women could display in public, and this lex Oppia remained in effect for almost twenty years, until Roman female citizens staged public protests and successfully achieved its repeal. In a final war of extermination, waged between 149 and 146 BCE, the Romans used their overwhelming advantage in manpower, ships, and other resources to bring the five-centuries-long hegemony of Carthage in the western Mediterranean to an end.

With an unrelenting drive to war, the Romans continued to draft, train, and field extraordinary numbers of men for combat. Soldiers, conscripted at age seventeen or eighteen, could expect to serve for up to ten years at a time or even longer. The Roman historian Livy recounted a speech, perhaps imagined, given in 171 BCE by Spurius Ligustinus, as an example of a soldier battle-hardened from more than twenty years of service. After recounting his many campaigns in Macedonia, Syria, and Spain, fifty-year-old Ligustinus concluded with this claim: “So long as anyone who is calling up an army will judge me to be a suitable soldier, never will I try to be excused” (Livy, History of Rome, 42.34.13). With so many men devoted to war for such long spans of time, the war ethos became deeply embedded in the ideals of every generation. After 200 BCE, the Romans unleashed this successful war machine on the kingdoms of the eastern Mediterranean—with devastating results. In 146 BCE, the same year they annihilated what was left of Carthage, the Romans obliterated the great Greek city-state of Corinth, killing all its adult males and selling all its women and children into slavery. Rome’s monopoly of power over the entire Mediterranean basin was now unchallenged.

More information

A mosaic of Roman farmers and soldiers. The mosaic features soldiers riding on horses on one side while in the center several human figures attend to horses and cattle. Below that a group of birds are being herded into an enclosure and two figures wrangle dogs. On the other side several figures sit with animals and another figure holds their hands up to a tree. A decorative border surrounds the mosaic.

Roman military forces served under men who knew they could win not just glory and territory for the state but also enormous rewards for themselves. They were talented men driven by burning ambition, from, in the 200s BCE, Scipio Africanus, the conqueror of Carthage (a man who claimed that he personally communicated with the gods), to Julius Caesar (100–44 BCE), the great generalissimo of the 50s BCE. Julius Caesar’s eight-year-long cycle of Gallic wars was said to have resulted in the deaths of about 1 million Gauls and the enslavement of another million. Western Afro-Eurasia had never witnessed war on this scale; it had no equal anywhere, except in China.

POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS AND INTERNAL CONFLICT The conquest of the Mediterranean placed unprecedented power and wealth in the hands of a few men and women in the Roman social elite. The rush of battlefield successes had kept Romans and their Italian allies preoccupied with the demands of army service overseas. Once this process of territorial expansion slowed, social and political problems that had been lying dormant began to resurface.

Following the traditional date of its foundation in 509 BCE, the Romans had lived in a state that they called the “public thing,” or res publica (hence, the modern word republic). In this state, policy and rules of behavior issued from the Senate—a body of permanent members, 300 selected from among Rome’s most powerful and wealthy citizens (by definition, male)—and from popular assemblies of the citizens. Every year the citizens elected the officials of state, principally two consuls who held power for a year and commanded the armies. The people also annually elected ten men who, as tribunes of the plebs (“the common people”), held the task, often not fulfilled, of protecting the common people’s interests against those of the rich and the powerful. In severe political crises, sometimes one man was appointed, a dictator, whose words, dicta, were law and who held absolute power over the state for no longer than six months. These institutions, originally devised for a city-state, however, were not always well suited to ruling a Mediterranean-sized empire.

By the second century BCE, Rome’s power elites were exploiting the wealth from its Mediterranean conquests to acquire huge tracts of land in Italy and Sicily. They then imported enormous numbers of enslaved peoples from all around the Mediterranean to work this land. Free citizen farmers, the backbone of the army, were driven off their lands and into the cities. The result was a severe agrarian and recruiting crisis. In 133 and 123–121 BCE, two tribunes, the brothers Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, tried—much as Wang Mang would in China more than a century later—to address these inequalities. The Gracchi brothers attempted to institute land reforms guaranteeing to all of Rome’s poor citizens a basic amount of land that would qualify them for army service. But political enemies assassinated the elder brother, Tiberius, and orchestrated violent resistance that drove the younger brother, Gaius, to his death at the hands of an angry mob. Thereafter, the landless Roman citizens looked not to state institutions but to army commanders, to whom they gave their loyalty and support, to provide them with land and a decent income. These generals became increasingly powerful and started to compete with one another, ignoring the Senate and the traditional rules of politics. As generals sought control of the state and their supporters took sides, a long series of civil wars occurred, lasting from 90 BCE to the late 30s BCE. The Romans now turned inward on themselves the tremendous militaristic resources built up during the conquest of the Mediterranean.

Emperors, Authoritarian Rule, and Administration

It is ironic that the most warlike of all ancient Mediterranean states was responsible for creating the most pervasive and long-lasting peace of its time—the Pax Romana (“Roman Peace”; 25 BCE–235 CE). Worn out by half a century of savage civil wars, by the 30s BCE the Romans, including their warlike governing elite, were ready to change their values. They were now prepared to embrace the virtues of peace. But political stability came at a price: authoritarian one-man rule. Peace depended on the power of one man who possessed enough authority to enforce an orderly competition among Roman aristocrats. Ultimately, Julius Caesar’s adopted son, Octavian (63 BCE–14 CE), would reunite the fractured empire and emerge as undisputed master of the Roman world.

Octavian concentrated immense wealth and the most important official titles and positions of power in his own hands. Signaling the transition to a new political order in which he alone controlled the army, the provinces, and the political processes in Rome, Octavian assumed a new name, Augustus (“the Revered One”)—much as the Qin emperor Zheng had assumed the new title of Shi Huangdi (the first “August Emperor”)—as well as the traditional republican roles of imperator (“commander in chief,” or emperor), princeps (“first man”), and Caesar (a name connoting his adoptive heritage, but which over time became a title assumed by imperial successors).

More information

A full-size statue of Julius Caesar wearing a breastplate and a cape draped over his shoulders.

Rome’s subjects tended to see these emperors as heroic or semidivine beings in life and to think of the good ones as becoming gods on their death. Yet emperors were always careful to present themselves as civil rulers whose power ultimately depended on the consent of Roman citizens and the might of the army. They contrasted themselves with the image of “king,” a role the Romans had learned to detest from the monarchy they themselves had long ago overthrown to establish their Republic in 509 BCE. The emperors’ powers were nevertheless immense. Many of them deployed their powers arbitrarily and whimsically, exciting a profound fear of emperors in general. One such emperor was Caligula (r. 37–41 CE), who presented himself as a living god on earth, engaged in casual incest with his sister, and kept books filled with the names of persons he wanted to kill. His violent behavior was so erratic that people thought he suffered from serious mental disorders; those who feared him called him a living monster.

Being a Roman emperor required finesse and talent, and few succeeded at it. Of the twenty-two emperors who held power in the most stable period of Roman history (between the first Roman emperor, Augustus, and the early third century CE), fifteen met their end by murder or suicide. As powerful as he might be, no individual emperor alone could govern an empire of such great size and population, encompassing a multitude of languages and cultures. He needed institutions and competent people to help him. In terms of sheer power, the most important of these was the army. Consequently, the emperors systematically transformed the army into a full-time force. Men now entered the imperial army not as citizen volunteers but as paid professionals who signed up for long fixed terms of service and swore loyalty to the emperor and his family. And it was part of the emperor’s image to present himself as a victorious battlefield commander, inflicting defeat on the “barbarians” who threatened the empire’s frontiers. Such a warrior emperor was a “good” emperor. As in China, the powerful structure of the family in Roman society meant that women in the imperial family wielded unusual power. Wives of emperors—from Livia, the wife of the first emperor, Augustus, to Julia Domna and other wives of the Severan emperors at the beginning of the third century—often bore the honorific title of Augusta and were real powers at court.

More information

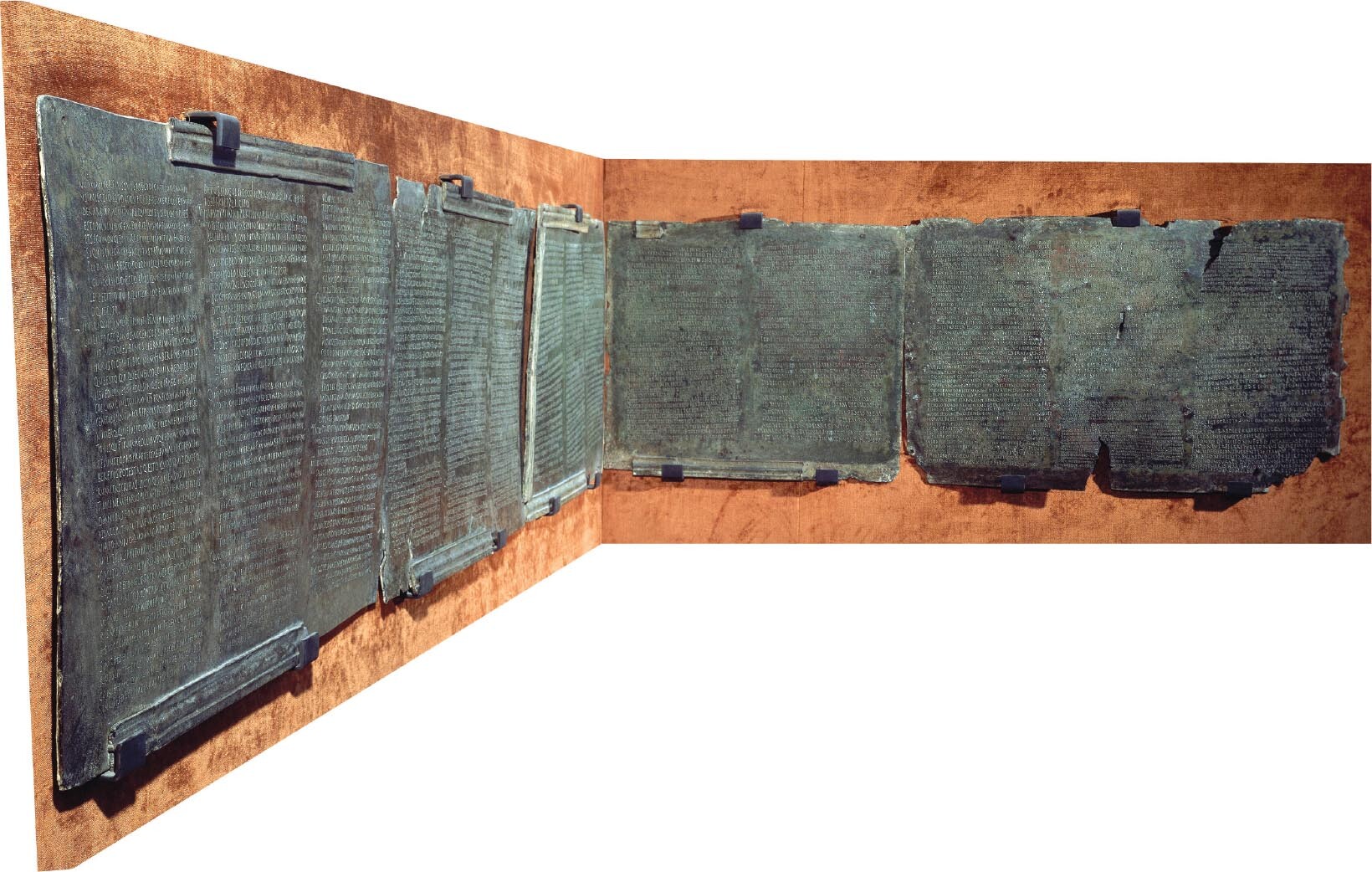

A photo of several bronze tablets on a wall with neat columns of ancient writing.

For most emperors, however, governance was largely a daily chore of listening to complaints, answering petitions, deciding court cases, and hearing reports from civil administrators and military commanders. By the second century CE, the empire encompassed more than forty administrative units called provinces. As in Han China, each had a governor appointed or approved by the emperor; but unlike Han China, which had its formal Confucian-trained bureaucracy with ranks of senior and junior officials, the Roman Empire of this period was relatively understaffed in terms of central government officials. The emperor and his provincial governors depended very much on local help, sometimes aided by enslaved administrators and freedmen (formerly enslaved) serving as government bureaucrats. With a limited staff of full-time assistants and an entourage of friends and acquaintances, the governor was expected to guarantee peace and collect taxes for his province. For many essential tasks, though, especially the collection of imperial taxes, even these helpers were insufficient. The state often had to rely on private companies, a measure that set up a tension between the profit motives of the “publicans”—as the men in the companies that took up government contracts were called—and the expectations of fair government among the empire’s subjects.

AN EMPIRE OF LAW The sometimes arbitrary power of the emperors was balanced by a more uniform system of laws and courts than had ever been seen in the Mediterranean world. The numerous laws enunciated by emperors, the Senate, and other imperial officials were commented on and developed by many generations of jurists—private legal experts whose authority in interpreting the law strongly affected its practice. One of them, named Gaius (c. 150 CE), produced the first known law textbook for the Roman law school in Beirut. Often the biggest event that any town experienced was the annual appearance of the Roman governor to hear important court cases in the local town forum. Even if courts and judges were often thought to be biased and corrupt, they nevertheless offered greater access to more persons than ever before. These courts arbitrated everything from small thefts and property disputes to serious matters like assault and homicide. From archives, histories, and novels, we know that everyday people—like a Jewish woman named Babatha in the province of Arabia and peasant farmers in the province of Africa—expected to have fair access to the courts and to the rule of law. A Christian missionary named Paul, facing a capital charge of sedition before the governor of Judea, could appeal to be heard by the Roman emperor and have his appeal respected.

More information

A photo of an excavated Roman town. The town features stone houses. Paved streets and sidewalks run between the streets. There are several trees in the background of the photo.

Town and City Life

Due to the conditions of peace and the wealth that imperial unity generated, core areas of the empire—central Italy, southern Spain, northern Africa, and the western parts of present-day Turkey—had surprising densities of urban settlements.

MUNICIPALITIES Inasmuch as these towns imitated Roman forms of government, they provided the backbone of local administration for the empire. This system of municipalities would become a permanent legacy of Roman government to the western world. Some of our best records of how these towns operated come from Spain, which later flourished as a colonial power that exported Roman forms of municipal life to the Americas. Remarkable physical records of such towns come from Pompeii and Herculaneum, in southern Italy. Both towns were almost perfectly preserved by the ash and debris that buried them following the explosion of a nearby volcano, Mount Vesuvius, in 79 CE.

Towns often were walled, and inside those walls the streets and avenues ran at right angles. A large, open-air, rectangular area called the forum dominated the town center. Around it clustered the main public buildings: the markets, the main temples of principal gods and goddesses, and the building that housed city administrators. Residential areas featured regular blocks of houses, usually roofed with bright red terra-cotta tiles, close together and fronting on the streets. Larger towns like Ostia, the port city of Rome, contained large apartment blocks that were not much different from the four- and five-story buildings in any modern city. In the smaller towns, sanitary and nutritional standards were reasonably good. Human skeletons discovered at Herculaneum in the 1970s revealed people in good health, with much better teeth than many people have today—a difference explained largely by the lack of sugar in their diet.

More information

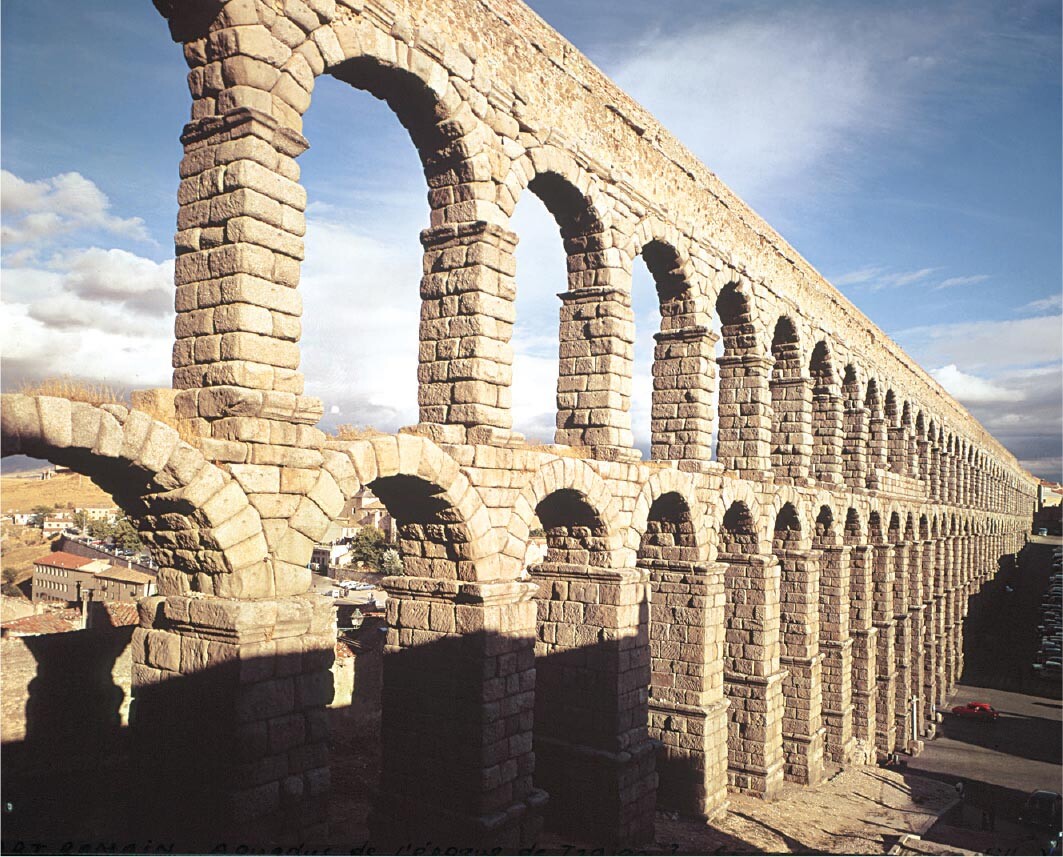

An aqueduct with multiple arches in two rows on top of each other.

ROME The imperial metropolis of Rome was another matter. With well over a million inhabitants, it was larger than any other urban center of its time; Xianyang and Chang’an—the Qin and Han capitals, respectively—each had a population of between 300,000 and 500,000. Rome’s inhabitants were privileged, because there the emperor’s power and state’s wealth guaranteed them a basic food supply. Thirteen huge and vastly expensive aqueducts provided a dependable daily supply of water, sometimes flowing in from great distances. Most adult citizens regularly received a free, basic amount of wheat (and, later, olive oil and pork). But living conditions were often appalling, with people jammed into ramshackle high-rise apartments that threatened to collapse on their renters or go up in flames. And people living in Rome constantly complained of crime and violence. Even worse was the lack of sanitary conditions—despite the sewage and drainage works that were wonders of their time. Rome was disease ridden; its inhabitants died from infections at a fearsome rate. Malarial infections were particularly bad. Medical texts and magical spell books alike contained remedies for what they called “quartan ague,” or a fever that recurs every four days, a symptom of malaria. Not surprisingly, the city required a substantial input of immigrants every year just to maintain its population.

More information

A mosaic of several Roman gladiators.The names of the gladiators hover above their figures. The names are Baccibus, Astacius, another Astacius, Astivus Iaculator, and Rodan. Two gladiators, Astivus and Rodan, are shown lying dead on the ground with the Greek letter theta above them. The second Astacius stands over Astivus with a knife. The first Astacius and Iaculator stand in the background while holding small thin flags in one hand. Baccibus is partially cut off by the edge of the photo but is holding some sort of rod in one hand and looks poised to strike with it.

A glass cup with designs of pairs of fighting gladiators. There is text above the gladiatorial scene and a chip in the rim of the cup.

MASS ENTERTAINMENT Towns large and small tended to have two major entertainment venues: a theater, adopted from Hellenistic culture and devoted to plays, dances, and other popular events, and an amphitheater, a Roman innovation with a much larger seating capacity that surrounded the oval performance area at its center. The emperor Vespasian and his son the emperor Titus completed the iconic Flavian Amphitheater (known today as the Colosseum) in Rome and dedicated it in 80 CE. In amphitheaters across the Mediterranean world, Romans could stage exotic beast hunts and gladiatorial matches for the enjoyment of huge crowds of appreciative spectators. While amphitheaters could be flooded to stage naval battles, Rome itself had a specially engineered structure called a naumachia, or “ship fighting center,” that could be filled with water from the Tiber River and then used for reenactments of sea battles. The public entertainment facilities in Roman towns stressed the importance of gatherings in which citizens participated in civic life, as compared with the largely private entertainment of the Han elite.

Indigenous Peoples and Empire

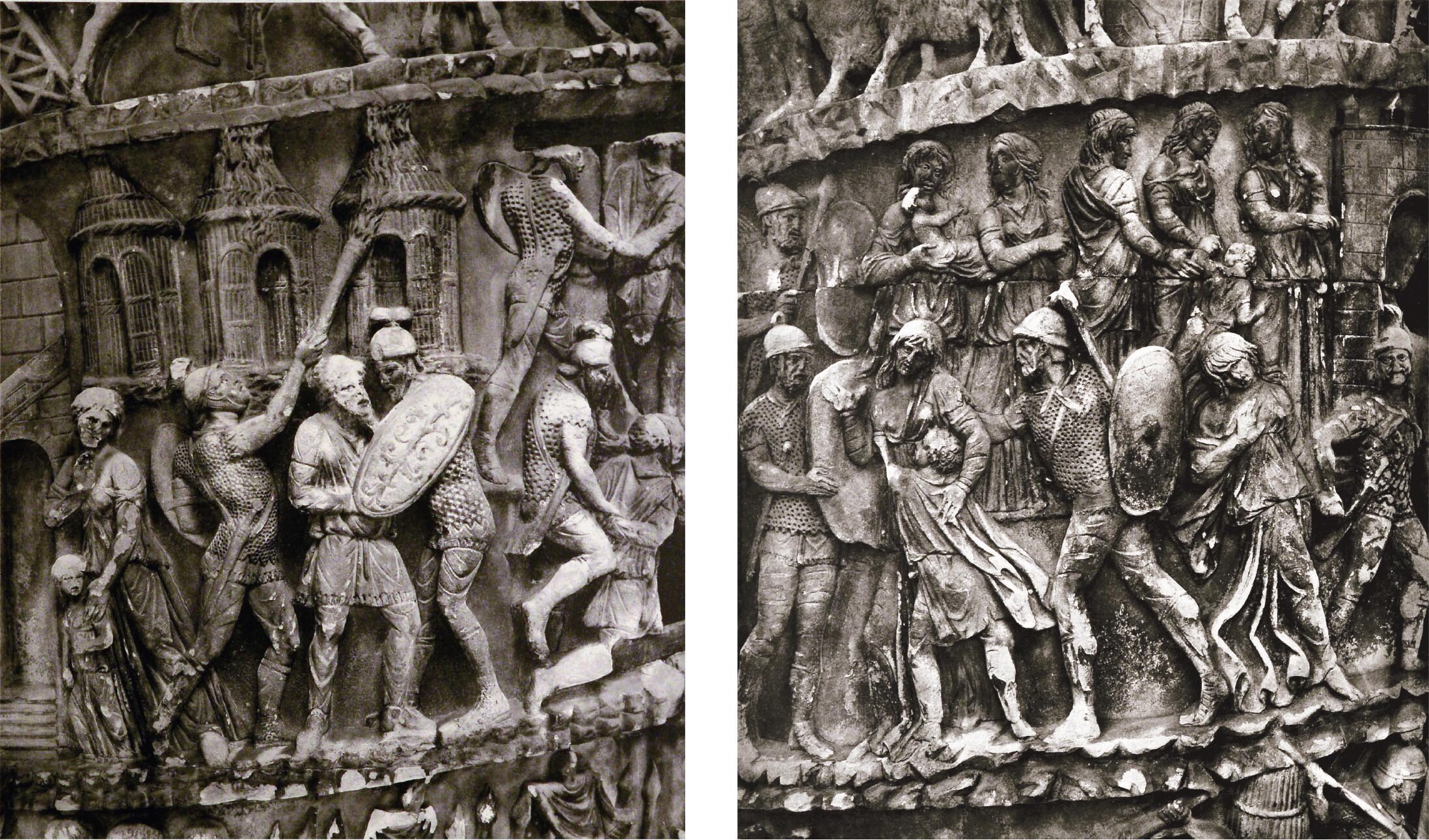

The great conquests of the Han and Roman Empires necessarily involved the armed domination of peoples already living in the spaces they conquered. Given the sheer size of these empires, the situations in which these indigenous peoples found themselves varied immensely. In some cases, ethnic groups—like the Musulamii in Africa led by the rebel Tacfarinas in the 20s CE, or the Iceni people in Britain led by their queen Boudicca in the early 60s CE—staged armed insurrections against the imperial state. The greatest internal wars against the empire were fought by Jewish peoples in Judea in a long war in the late 60s CE and a second war led by the charismatic leader Bar Kokhba in the early 130s CE. Both wars were motivated by the religious ideology shared by a large number of Jews in Judea, which held that the one God, his people, and their traditions had an absolute precedence over both empire and emperor. Such rebellions often failed, and the long-term Roman domination frequently led to the gradual erasure of indigenous cultures. The conquest of the Etruscans, peoples living north of Rome, eventually led to the extinction of Etruscan culture, language, and social order. While these destructions of indigenous peoples and their lands were not technically genocidal in a modern sense, they were still examples of “ethnocide”: the death of the people’s identity and culture. Many indigenous peoples, however, showed surprising resilience to Roman domination. Some of the Maures in Africa, for example, maintained their languages, cultural norms, and types of self-rule up to the end of the empire.

On the other side of the coin, imperial powers attempted to acculturate conquered peoples. They did so not by the use of public school systems and mass media (which did not exist then) but by encouraging the conquered to imitate what the imperial power portrayed as the better, superior culture of the conquering state: its language and literature, paved roads, public baths, magnificent theaters, aqueducts, and other spectacular buildings. In this way, indigenous peoples like the Sabines and Marrucini in Italy and the Turdetani and Bastuli in southern Iberia gradually lost their own languages and cultures and became Roman. Many local elites inside the empire were attracted by the advantages of imperial rule and gradually adopted Roman speech, ideas, and way of life. By contrast, indigenous communities along the outer frontiers farther removed from the military might of Rome, like the Gallic, Germanic, and Gothic peoples along the northern periphery of the empire, were better able to maintain their independence. They even managed to inflict serious defeats on Roman armies, as Germanic groups commanded by their leader Arminius did in 9 CE, destroying three Roman legions. Roman authorities had to deal with these peoples either by offering them paid service in units of the Roman army (both Tacfarinas and Arminius had served in the Roman army), by buying off their leaders with annual subsidies, or by other diplomatic means. Having relatively large populations and inhabiting huge expanses of land in the north, these particular frontier peoples successfully maintained their languages, cultures, and identities even after the end of the empire itself.

More information

A section of a victory column depicting soldiers setting fire to a village. Two soldiers look like they are attacking villagers and a mother and child look on from the side.

A section of a victory column depicting soldiers selling women and children into slavery. Several soldiers are grabbing the arms and hands of women, including one woman who has a child clinging to her torso. There is line of women and children with a soldier with a weapon behind them.

More information

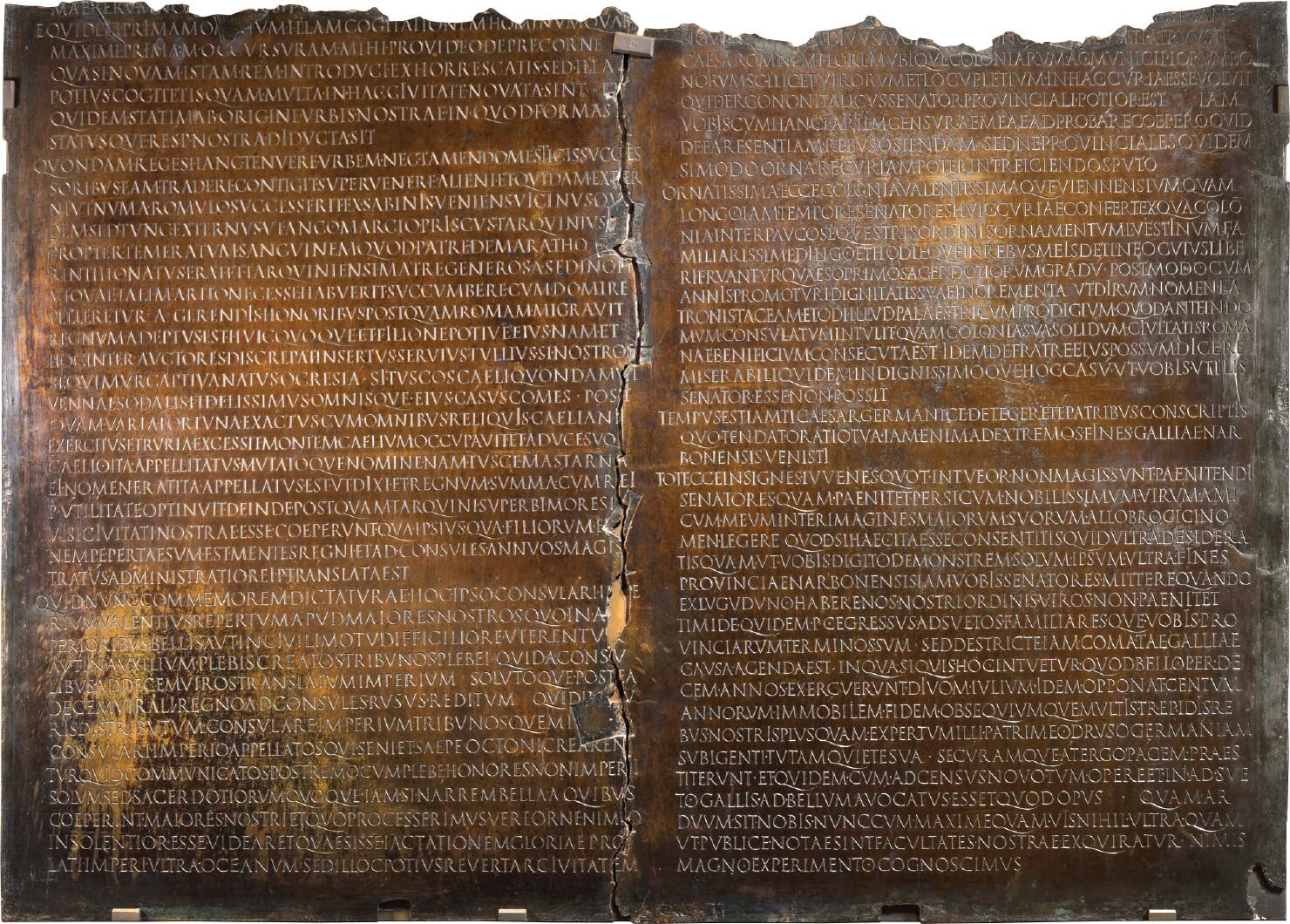

Bronze tablets with neat lines of ancient Latin script.

The Economy and New Scales of Production

Rome achieved staggering transformations in the production of agricultural, manufactured, and mined goods. Public and private demand for metals, for example, led the Romans to mine massive quantities of lead, silver, and copper in Spain. Evidence from Mediterranean shipwrecks similarly indicates a seaborne trade on an unprecedented scale. The area of land surveyed and cultivated rose steadily throughout this period, as Romans reached into arid lands on the periphery of the Sahara Desert to the south and opened up heavily forested regions in present-day France and Germany to the north. (See Map 7.4.)

More information

A photo of a road made of stones. The are rocks lining part of the path and grass along the sides.

The Romans also built an unprecedented infrastructure of roads to connect far-flung parts of their empire. Although many roads did not have the high-quality flagstone paving and excellent drainage exhibited by highways in Italy, such as the Via Appia, most were systematically marked by milestones (for the first time in this part of the world) so that travelers would know their precise location and the distance to the next town. Also for the first time, complex land maps and itineraries specified all major roads and distances between towns. Adding to the roads’ significance was their deliberate coordination with Mediterranean sea routes to support the smooth and safe flow of traffic, commerce, and ideas on land and at sea.

More information

Map 7.4 is titled, Pax Romana: The Roman Empire in the Second Century C E. Shaded regions indicate Roman territory under Pax Romana (Western Europe including southern England, Spain, France, Italy, North Africa, the Balkans, Greece, Turkey, Egypt, and the Levant, as well as territory occupied after 106 C E Armenia, Assyria, and Mesopotamia). This map also includes defense works (Antonine Wall and Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, as well as Limes in Germany and isolated walls northwest of the Black Sea), African fortifications (southwest of Carthage), numerous Main Roman roads, many Roman trading cities and important provincial capitals (from west to east: Corduba, Burdigala, Narbo, Londinium, Carthage, Rome, Corinth, Alexandria, Antioch), sea-lanes that criss-cross the Mediterranean, numerous legionary bases, and naval base (west-east, Caesarea, Ravenna, Carnuntum, Alexandria, Antioch, Trapezus). Traded items include metals, grain, wine, oil, fish, slaves, marble, ceramics, and amber.

MAP 7.4 | Pax Romana: The Roman Empire in the Second Century CE

The Roman Empire enjoyed remarkable peace and prosperity in the second century CE. Economic production increased, and Roman culture expanded throughout the realm.

- According to the map, what commodities cluster in which regions? With what groups did Romans trade beyond their empire, and for what commodity in particular?

- What are some of the major sea-lanes and roads linking the different parts of the empire?

- What do you note about the locations of legionary bases and naval bases? What is the strategic value of their locations? How are the limits of empire delineated?

The mines produced copper, tin, silver, and gold—out of which the Roman state produced the most massive coinage known in the western world before early modern times. Coinage facilitated the exchange of commodities and services, which now carried standard values. Throughout the Roman Empire, from small towns on the edge of the Sahara Desert to army towns along the northern frontiers, people appraised, purchased, and sold goods in coin denominations. Taxes were assessed and hired laborers were paid in coin. The economy in its leading sectors functioned more efficiently because of the production of coins on an immense scale (paralleled only by the coinage output of Han dynasty China and its successors).

Roman mining, as well as other sizable operations, relied on “chattel slaves”—human beings purchased as private property. The massive concentration of wealth and enslaved people at the center of the Roman world led to the first large-scale commercial plantation agriculture, along with the first technical handbooks on how to run such operations for profit. It also led to dramatic slave wars, such as the Sicilian Revolt of 135–132 BCE and the Spartacus War of 73–71 BCE, although the latter began among enslaved trainees in a school for gladiators. The plantations specialized in products destined for the big urban markets: wheat, grapes, and olives, as well as cattle and sheep. Such developments rested on a bedrock belief that private property and its ownership were sacrosanct. In fact, the Roman senator Cicero argued that the defense and enjoyment of private property constituted basic reasons for the existence of the state. (See Global Themes and Sources: Primary Source 7.2.) Roman law more clearly defined and more strictly enforced the rights of the private owner than any previous legal system had done. The extension of private ownership of land and other property to regions having little or no prior knowledge of it—Egypt in the east, Spain in the west, the lands of western Europe—was one of the most enduring effects of the Roman Empire.

ROME THE POLLUTER Sometimes the size of empires must be measured in terms of side effects. The Roman Empire required huge resources, a need fulfilled through extensive mining. The result was pollution on a scale never previously witnessed, which can be traced everywhere in the environment. The copper mines at Phaeno (modern Faynan), in southern Jordan in the Roman province of Arabia, offer a good example. The deleterious effects of copper mining on the local population are clearly traceable in the metal (copper and lead) content in the bones of excavated human remains. Mining pollution, from Phaeno and other mining ventures in Britain, Spain, and elsewhere, can even be seen on a global scale. Ice core samples taken from the ice sheets of Greenland reveal concentrations of isotopes of copper and lead whose levels peaked in the first centuries CE, clearly the result of airborne pollutants produced by the colossal Roman mining operations. Other signs of pollution have also been found in lake sediments in Sweden, dated again to the first centuries CE. Although pollution from mining and metal production occurred in other territories, such as Song dynasty China, the Roman Empire seems to have been the world’s first global-scale polluter. The demands of the empire similarly led to massive exploitation of woodlands; wood was used as building timber and to produce charcoal, which heated everything from private homes to enormous public bath complexes. The deforestation of lands for both these purposes, as well as the hunting of wild animals for food and entertainment, severely compromised the ecologies of some animal populations, even leading to the extinction of some species, like the elephants that had once been found in present-day Morocco.

The Rise of Christianity

Over centuries, Roman religion had cultivated a dynamic world of gods, spirits, and demons that was characteristic of earlier periods of Mediterranean history. Christianity took shape in this richly pluralistic world. Its foundations lay in a direct confrontation with Roman imperial authority: the trial of Jesus. After preaching the new doctrines of what was originally a sect of Judaism, Jesus was found guilty of sedition and executed by means of crucifixion—a standard Roman penalty—as the result of a typical Roman provincial trial overseen by a Roman governor, Pontius Pilatus.

Although we do have contemporary mentions of Pontius Pilatus, the governor, no historical reference to Jesus survives from his own lifetime. Shortly after the crucifixion, Paul of Tarsus, a Jew and a Roman citizen from southeastern Anatolia, claimed to have seen Jesus in full glory outside the city of Damascus. Paul and the Mediterranean communities to whom he preached and wrote letters between 40 and 60 CE referred to Jesus as the Anointed One (the Messiah, in keeping with Jewish expectations) or the Christ—ho Christos in common or Koine Greek, the dominant language in the eastern Mediterranean thanks to Hellenism. Only many decades later did accounts that came to be called the Gospels—such as Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—describe Jesus’s life and record his sayings. Jesus’s preaching drew not only on Jewish models but also on the Egyptian and Mesopotamian image of the great king as shepherd of his people (see Chapter 3). With Jesus, this image of the good shepherd took on a new, personal closeness. Not a distant monarch but a preacher, Jesus had set out on God’s behalf to gather a new, small flock.

Through the writings of Paul and the Gospels, both written in Koine Greek, this image of Jesus rapidly spread beyond Palestine (where Jesus had preached only to Jews and only in the local language, Aramaic). Core elements of Jesus’s message, such as the responsibilities of the well-off for the poor and the promised eventual empowerment of “the meek,” appealed to many ordinary people in the wider Mediterranean world. But it was the apostle Paul who was especially responsible for reshaping this message for a wider audience. While Jesus’s teachings were directed at villagers and peasants, Paul’s message spoke to a world divided by religious identity, wealth, slavery, and gender differences: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). This new message, universal in its claims and appeal, was immediately accessible to the dwellers of the towns and cities of the Roman Empire.

Just half a century after Jesus’s crucifixion, the followers of Jesus saw in his life not merely the wanderings of a Jewish charismatic teacher, but a head-on collision between “God” and “the world.” Jesus’s teachings came to be understood as the message of a divine being who for thirty years had moved (largely unrecognized) among human beings.

Jesus’s followers formed a church: a permanent gathering entrusted to the charge of leaders chosen by God and fellow believers. For these leaders and their followers, death offered a defining testimony for their faith. Some of these Christians actually hoped for the confrontation of a Roman trial and the opportunity to offer themselves as witnesses (martyrs) for their faith. At first, such trials and persecutions of Christians were sporadic and were responses to local concerns. Not until the emperor Decius, in the mid-third century CE, did the state direct an empire-wide attack on Christians. But Decius died within a year of launching this assault, and Christians interpreted their persecutor’s death as evidence of the hand of God in human affairs. By the last decades of the third century CE, Christian communities of various kinds, reflecting the different strands of their movement through the Mediterranean as well as the local cultures in which they settled, were present in every society in the empire.

The Limits of Empire

The limitations of Roman force were a pragmatic factor in determining who belonged in the empire and was subject to it and who was outside it and therefore excluded. The Romans pushed their authority in the west to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, and to the south they drove it to the edges of the Sahara Desert. In both cases, there was little additional useful land available to dominate. Roman power was blocked, however, in the east by the Parthians and then the Sasanians and in the west by the Goths and other Germanic peoples. (See again Current Trends in World History: Han China, the Early Roman Empire, and the Silk Roads.)

THE PARTHIANS AND SASANIANS On Rome’s eastern frontiers, powerful Romans such as Marcus Crassus in the mid-50s BCE, Mark Antony in the early 30s BCE, and the emperor Trajan around 115 CE wished to imitate the achievements of Alexander the Great and conquer the arid lands lying east of Judea and Syria. Crassus and Antony failed miserably, stopped by the Parthian Empire and its successor, the Sasanian Empire. The Romans, under Trajan, briefly annexed the provinces of Armenia and Mesopotamia but abandoned them soon thereafter. The Parthian people had moved south from present-day Turkmenistan and settled in the region comprising the modern states of Iraq and Iran. Parthian social order was founded on nomadic pastoralism and a war capability based on technical advances in mounted horseback warfare. Reliance on horses made the Parthian style of fighting highly mobile and ideal for warfare on arid plains and deserts. They perfected the so-called Parthian shot: a reverse arrow shot from a bow with great accuracy at long distance and from horseback at a gallop. On the flat, open plains of Iran and Iraq, the Parthians had a decisive advantage over slow-moving, cumbersome mass infantry formations that had been developed for war in the Mediterranean. Eventually the expansionist states of Parthia and Rome became archenemies: they confronted each other in Mesopotamia for nearly four centuries.

The Sasanians expanded the technical advances in mounted horseback warfare that the Parthians had used so successfully in open-desert warfare against the slow-moving Roman mass infantry formations. King Shapur I (r. 240–270 CE) exploited the weaknesses of the Roman Empire in the mid-third century CE, even capturing the Roman emperor Valerian. One early Christian writer, Lactantius, used Valerian’s fate at the hands of the Sasanians—he was forced to serve in captivity as a footstool for the Sasanian king, then flayed and stuffed after death to stand in the Sasanian throne room as a warning to ambassadors—as a lesson for what happens to those who persecute Christians. As successful as the Parthians and the Sasanians were in fighting the Romans, however, they could never permanently challenge Roman sway over Mediterranean lands. Their decentralized political structure limited their coordination of resources, and their horse-mounted style of warfare was ill suited to fighting in the more rocky and hilly environments of the Mediterranean world. (See Chapter 8 for more on the Sasanians.)

More information

A monument made of clay shows eight men and four barrels on a ship. The ships has many oars and figures on the front and back depicting some sort of animal.

GERMAN AND GOTHIC “BARBARIANS” In the lands across the Rhine and Danube, to the north, once again environmental conditions largely determined the limits of empire. The long and harsh winters, combined with excellent soil and growing conditions, produced hardy, dense population clusters scattered across vast distances. These illiterate, kin-based agricultural societies had changed little since the first millennium BCE. And because their warrior elites still engaged in armed competition, war and violence tended to characterize their connections with the Roman Empire.

As the Roman Empire fixed its northern frontiers along the Rhine and Danube Rivers, two factors determined its relationship with the Germans and Goths on the rivers’ other sides. First, these small societies had only one big commodity for which the empire was willing to pay big money: human bodies. So the slave trade out of the land across the Rhine and Danube became immense: gold and silver (especially in the form of coins), wine, armaments, and other luxury items flowed across the rivers in one direction in exchange for the enslaved in the other. Second, the wars between the Romans and these societies were unremitting, as every emperor faced the expectation of dealing harshly with the “barbarians.” These connections, involving arms and violence, were to enmesh the Romans ever more tightly with the tribal societies to the north.

Current Trends in World History

Han China, the Early Roman Empire, and the Silk Roads

This chapter offers detailed information allowing for a comparison of the globalizing empires of imperial Rome and Han China. To what extent, however, were these powerful, contemporary forces in contact with each other? Because the Roman Empire and Han China were separated by 5,000 miles, harsh terrain, and the powerful Parthian Empire, scholars have wondered about their interaction and knowledge of each other. (See Map 7.5.) In the nineteenth century, European archaeologists created the term “Silk Road,” stressing the commercial linkages between these two great empires. (See Chapter 6 for more on the early Silk Roads.) Many twentieth-century historians have challenged this view, first, questioning the validity of the term due to its emphasis on silk exchange to the exclusion of other traded commodities, and, second, questioning the extent of direct, or even indirect, commercial exchanges between Han China and the Roman Empire. Some modern historians see the very idea of a Silk Road as part of a de-Europeanizing trend among global historians who are committed to elevating the Chinese as the true entrepreneurs of the age.

Already by the reign of Augustus, substantial amounts of Chinese silk were available in the Mediterranean world. David F. Graf observes that the late first-century BCE poets Virgil and Ovid have many references to Chinese silk. Another first-century BCE poet, Horace, was more explicit about the use of Chinese silks, writing that “the sheer and transparent qualities of serica [silk] dresses became a symbol of degeneracy of the emperors and aristocratic women, drawing condemnation.” In the late first century CE, natural historian Pliny the Elder commented somewhat disdainfully on trade with the Seres (the “Silk People”): “Though mild in character, the Chinese still resemble wild animals in that they shun the company of the rest of humankind and wait for trade to come to them.” While the Peutinger Table, a map (or itinerary) thought to reveal early first-century CE geographic knowledge, does not reach as far as China in the east, the Romans had sufficient information by the middle of the second century CE to enable mapmakers drawing on Ptolemy’s Geography to locate China and the rest of East Asia on their map of the world.

The Han emperor most responsible for beginning to expand Chinese influence westward, opening up trade routes to China’s west and gaining knowledge of western regions, was Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BCE). In 139 BCE, Wu sent an official, Zhang Qian, accompanied by more than a hundred men, on a mission to the west. The primary goal of this mission was to secure alliances with central Asian states, most importantly the Yuezhi, against the Xiongnu nomads, who threatened the Han at this time. On his way to the Yuezhi, Zhang Qian was detained by a Xiongnu chieftain for ten years, during which he married a Xiongnu woman and had children with her. While in captivity, Zhang Qian gathered information on the commodities from this region and beyond, including Bactria, India, and Persia. He shared this information when he eventually escaped and returned to the Han capital at Chang’an. In short, Wu’s diplomatic and military moves expanded Han China’s understanding of the west and knowledge of routes through which silk could be shipped westward.

A second major Chinese initiative regarding the west occurred around the end of the first century CE and the beginning of the second. Here, the leading figure was General Ban Ch’ao (brother of Ban Zhao, who wrote the Lessons for Women excerpted in Global Themes and Sources: Primary Source 7.3). Ban Ch’ao held the office of Protector of the Western Territories between 91 and 101 CE. He brought the whole of the Tarim Basin under Chinese rule and established a set of forts on routes leading westward. He dispatched one of his adjuncts, Gan Ying, to travel westward and gather information on regions thus far unexplored by the Chinese. Gan Ying did not reach Rome, though his mission was to do so. Nevertheless, journeying only as far as the Black Sea or the Persian Gulf, he did acquire much information about Rome and its dependent states.

The Roman Empire was known to the Chinese as Da Qin (the “Great Qin”). Gan Ying viewed Da Qin accurately in some respects and fantastically in others. Han reports from that period portrayed the Romans through their own spectacles, seeing Rome as “an idealized China, a Taoist utopia, a fictitious religious world divorced from reality.” According to Han accounts from that time, the first direct contact with the Roman Empire occurred during the ninth year of the reign of Huandi (166 CE), when a private Roman merchant arrived at the Chinese commandery on the central Vietnamese coast with “gifts of elephant tusks, rhinoceros horn, and tortoise shell” during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. The Chinese court was unimpressed by these offerings, even wondering if the reports of Rome’s power had been exaggerated.

Most of the Chinese silk that reached the Mediterranean regions came by sea via the route described in the Periplus Maris Erythraei (see Chapter 6), often through the Persian Gulf and Red Sea and then overland to ports along the coast of present-day Syria. But the overland route, which most scholars have called the Silk Road, was also in use at this time. The entry point for much Chinese silk was Palmyra. Trade through Palmyra reached its high point in the second century CE. To date, the largest quantity of silk found outside China and dated to ancient times has been discovered in Palmyra. The polychrome silk weaving found in Palmyra can be traced back to imperial Chinese workshops. The conclusion of the most recent scholarship on the Silk Roads and Chinese-Roman relations, according to Graf, is that “there was significant movement of peoples and goods along segments of the ‘Silk Route’ during the Roman imperial era,” but the relations between the Chinese and the Romans were still remote and “indirect.”

More information

The Peutinger table shows topographical features such as rivers and mountain ranges, roads, towns, and ports. It shows France, part of the Mediterranean Sea, and North Africa.

Source: David F. Graf, “The Silk Road between Syria and China,” in Trade, Commerce, and the State in the Roman World, edited by Andrew Wilson and Alan Bowman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 443–529 (quotations are from pp. 444, 460, 477–78).

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- What is the evidence for exchange between the Romans and the Han Chinese? What were the impediments to direct interaction between Rome and Han China?

- What did the Romans think about trade with Han China? What did the Chinese think of Rome?

- How does the evidence for interconnectivity between Rome and Han China influence your understanding of the comparative picture of these two globalizing empires?

EXPLORE FURTHER

Graf, David F., “The Silk Road between Syria and China,” in Trade, Commerce, and the State in the Roman World, edited by Andrew Wilson and Alan Bowman (2018), pp. 443–529.

Hansen, Valerie, The Silk Road: A New History (2012).

Liu, Xinru, The World of the Ancient Silk Road (2023).

More information

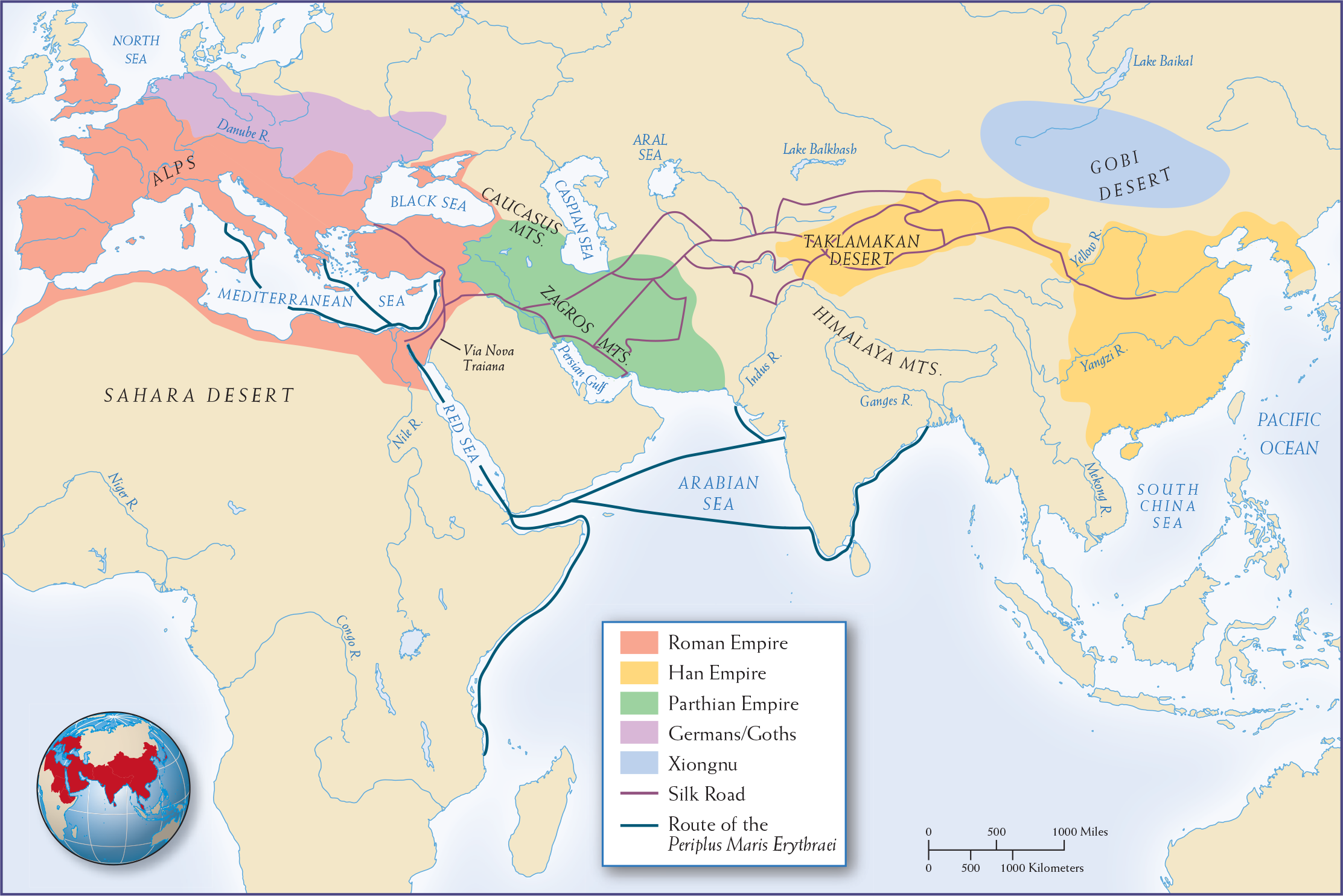

Map 7.5 is titled, Imperial Rome and Later (Eastern) Han China (c. 200 C E). The map shows the extent of the Roman Empire (the southern half of England, all of Western Europe south of the Danube, the Balkans, Greece, Turkey, and North Africa from Gibraltar to Syria); the Han Empire (modern China south of the Gobi desert, as well as the area of the Taklamakan Desert); Parthian Empire (Iraq and Iran); Germans/Goths (Europe north of the Danube River between the North Sea and the Black Sea); and Xiongnu (the area of the Gobi Desert). It also shows the route of the Silk Road from the center of the Han Empire west to Egypt and Turkey, as well as the route of the Periplus Maris Erythraei (from Italy and Greece down the Red Sea and along the Horn of Africa, as well as across the Arabian Sea to and along the coastline of India). Two small defense works are shown in northern England.

MAP 7.5 | Imperial Rome and Later (Eastern) Han China, c. 200 CE

Imperial Rome and the Later (Eastern) Han dynasty thrived simultaneously for about 200 years at the start of the first millennium CE. Despite their geographic spread and the Silk Roads running across Afro-Eurasia, the two empires did not have as much direct contact as one might expect.

- What major groups lived on the borders of imperial Rome and Han China?

- What were the geographical limits of the Roman Empire? Of Han China?

- Based on the map and your reading, what drew imperial Rome and Han China together? What kept them apart?

One of the main ways in which peoples beyond the northern frontier related to the empire was by military service. They were frequently found serving in “ethnic units” that were attached to the Roman army. As internal conflicts within the Roman Empire increased, there was more frequent recourse to the use of “barbarians” as soldiers and officers in its armed forces. The truly vast areas of the western Eurasian steppe lands harbored horse-mounted mobile populations. Groups known variously as Alans and Sarmatians, or more generally as Scythians or Goths, were involved in internal conflicts that pushed some of them to the edge of the empire and then across the Danube into the empire itself. These armed migrations became increasingly difficult for the empire to control. The effects for the peoples in the contact zone were often worse: caught in violent conflicts between enemies pressing in from the north and the heavy defenses of the empire to the south, some of these peoples simply went out of existence.

While the Han Empire fell in the early third century CE, the Roman Empire would arguably continue to exist politically for more than two more centuries, during which its history would become intertwined with the rise of Christianity, one of the world’s universalizing religions.

More information

A stone carving of a Roman legionary soldier and a German fighter. The Roman soldier is in his armor and helmet while the German fighter has long flowing hair and is swinging his sword. There is a thatched hut in the background.

Glossary

- Punic Wars

- Series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 to 146 BCE that resulted in the end of Carthaginian hegemony in the western Mediterranean, the growth of Roman military might (army and navy), and the beginning of Rome’s aggressive foreign imperialism.

- res publica

- Term (meaning “public thing”) used by Romans to describe their Republic, which was advised by a Senate and was governed by popular assemblies of free adult males, who were arranged into voting units, based on wealth and social status, to elect officers and legislate.

- Pax Romana

- Latin term for “Roman Peace,” referring to the period from 25 BCE to 235 CE, when conditions in the Roman Empire were relatively settled and peaceful, allowing trade and the economy to thrive.

- Augustus

- Latin term meaning “the Revered One”; title granted by the Senate to the Roman ruler Octavian in 27 BCE to signify his unique political position. Along with his adopted family name, Caesar, the military honorific imperator, and the senatorial term princeps, Augustus became a generic term for a leader of the Roman Empire.

- Christianity

-

New religious movement originating in the Eastern Roman Empire in the first century CE, with roots in Judaism and resonance with various Greco-Roman religious traditions. The central figure, Jesus, was tried and executed by Roman authorities, and his followers believed he rose from the dead. The tradition was spread across the Mediterranean by his followers, and Christians were initially persecuted—to varying degrees—by Roman authorities. The religion was eventually legalized in 312 CE, and by the late fourth century CE it became the official state religion of the Roman Empire.

Social and Gender Relations

Inside the empire, more significant than political forums and game venues were the personal relations that linked the rich and powerful with the mass of average citizens. Men and women of wealth and high social status acted as patrons, protecting and supporting dependents called “clients” who inhabited the lower classes. From the emperor at the top to the local municipal citizens at the bottom, these relationships were reinforced by generous distributions of food and entertainment from wealthy men and women to their people. The bonds between these groups in each city found formal expression in legal definitions of patrons’ responsibilities to clients; at the same time, this informal social code raised expectations that the wealthy would be public benefactors. The senator Pliny the Younger, for example, constructed a public library and a bathhouse for his hometown; funded a Latin teacher; and established a fund to support the sons and daughters of the formerly enslaved. The emperors at the very top were no different. In his autobiographical Res Gestae, Augustus documented the scale of his gifts to the Roman people, gifts that exceeded hundreds of millions of sesterces (standard bronze coins) in expenditures from his own pocket. A later emperor, Trajan, established a social scheme for feeding the children of poor Roman citizens in Italy—a benefaction that he advertised on coins and on arches in various towns in Italy.

While patronage was important, the family was at the very foundation of the Roman social order. Legally speaking, the authoritarian paterfamilias (“father of the family”) had nearly total power over his dependents, including his wife, children, and grandchildren and the men and women he enslaved. Imperial society heightened the importance of the basic family unit of mother, father, and children in the urban centers. Despite this patriarchal system, Roman women, even those of modest wealth and status, had much greater freedom of action and much greater control of their own wealth and property than did women in most Greek city-states. (See Global Themes and Sources: Primary Source 7.4.)

More information

A full-size statue of Claudia Antonia Tatiana of Aphrodisias, a woman with curly hair and a flowing dress. The face of the statue has large cracks in it and both hands are missing.

For example, Terentia, the wife of the republican senator Cicero (and a woman reminiscent of Ban Zhao, the female Han historian discussed earlier), bought and sold properties on her own, made decisions regarding her family and wealth without consulting her husband (much to his chagrin—he later divorced her), and apparently fared well following her separation from Cicero. Hortensia, during the throes of first-century BCE civil war, gave a public speech that decried the taxation without representation that wealthy Roman matrons endured. Wealthy women in the provinces, like Plancia Magna of Perge on the southern coast of Turkey, could be prodigious benefactors; for her generosity and leading patronage, Plancia was even named demiourgos (or magistrate) of the city in the second century CE. Claudia Antonia Tatiana, who lived in the Roman city of Aphrodisias in Asia Minor around 200 CE, held a place of prestige in the city; a statue honoring her stood by the door of the Council House in which the men met to govern.

More information

A torn thin sheet of wood with script written on it.

Terentia and Hortensia in Rome and Plancia and Tatiana in the provinces were educated, literate, connected, and in some control of their own lives—despite what the laws and ideas of Roman males might suggest. While exceptional, they are not mere exceptions. According to documents written on thin wooden plaques found in central Italy and on papyrus in the Roman province of Egypt, for example, the daily activities of even ordinary women included buying, loaning monies, selling, renting, and leasing, with no sign that the legal constraints subjecting them to male control had any significant effect on their dealings.