The Tang State

The rise of the powerful Tang Empire (618–907 CE) in China coincided with and in many ways paralleled Islam’s explosion out of Arabia and its dramatic spread throughout Afro-Eurasia. Once again the landmass had two centers of power, as Islam replaced the Roman Empire in counterbalancing the power and wealth of China. Now the two powerhouses competed for dominance in central Asia, sharing influences and even mobile populations that weaved back and forth across porous borders between them.

China was both a recipient of foreign influences and a source of influences on its neighbors. It was becoming the main hub of East Asian integration. Like the Umayyads and the Abbasids, the Tang dynasty, recovering the territory and confidence of the Han Empire, promoted a cosmopolitan culture. Under its rule, Buddhism, medicine, and mathematics from India gave China’s chief cities an international flavor. It seemed that the entire known world rubbed elbows in the streets of two of China’s largest cities, Chang’an and Luoyang: Buddhist monks from Bactria; Greeks, Armenians, and Jews from Constantinople; Muslim envoys from Samarkand and Persia; Vietnamese tributary missions from Annam; nomadic chieftains from the Siberian plains; officials and students from Korea; and monkish visitors from Japan. Ideas also traveled from Tang China eastward—notably to Korea and Japan, where Daoism and Buddhism made inroads. Similarly, Chinese statecraft, as expressed through the Confucian classics, struck the early Koreans and Japanese as the best model for their own state building.

Territorial Expansion under the Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty expanded the boundaries of the Chinese state and reestablished its dominance in East and central Asia. After the fall of the Han, China had faced a long period of political fragmentation (see Chapter 8). As had happened several times before, yet another sudden change in the course of the Yellow River caused extensive flooding on the North China plain and set the stage for the emergence of the Tang dynasty. Revolts ensued as the population faced starvation. Li Yuan, the governor of a province under the short-lived Sui dynasty (589–618 CE) marched on Chang’an and took the throne in 618 CE. He promptly established the Tang dynasty and began building a strong central government by increasing the number of provinces and doubling the number of government offices. By 624 CE, the initial steps of establishing the Tang dynasty were complete, but Li Yuan’s ambitious son, Li Shimin, forced his father to abdicate and took the throne in 627 CE.

More information

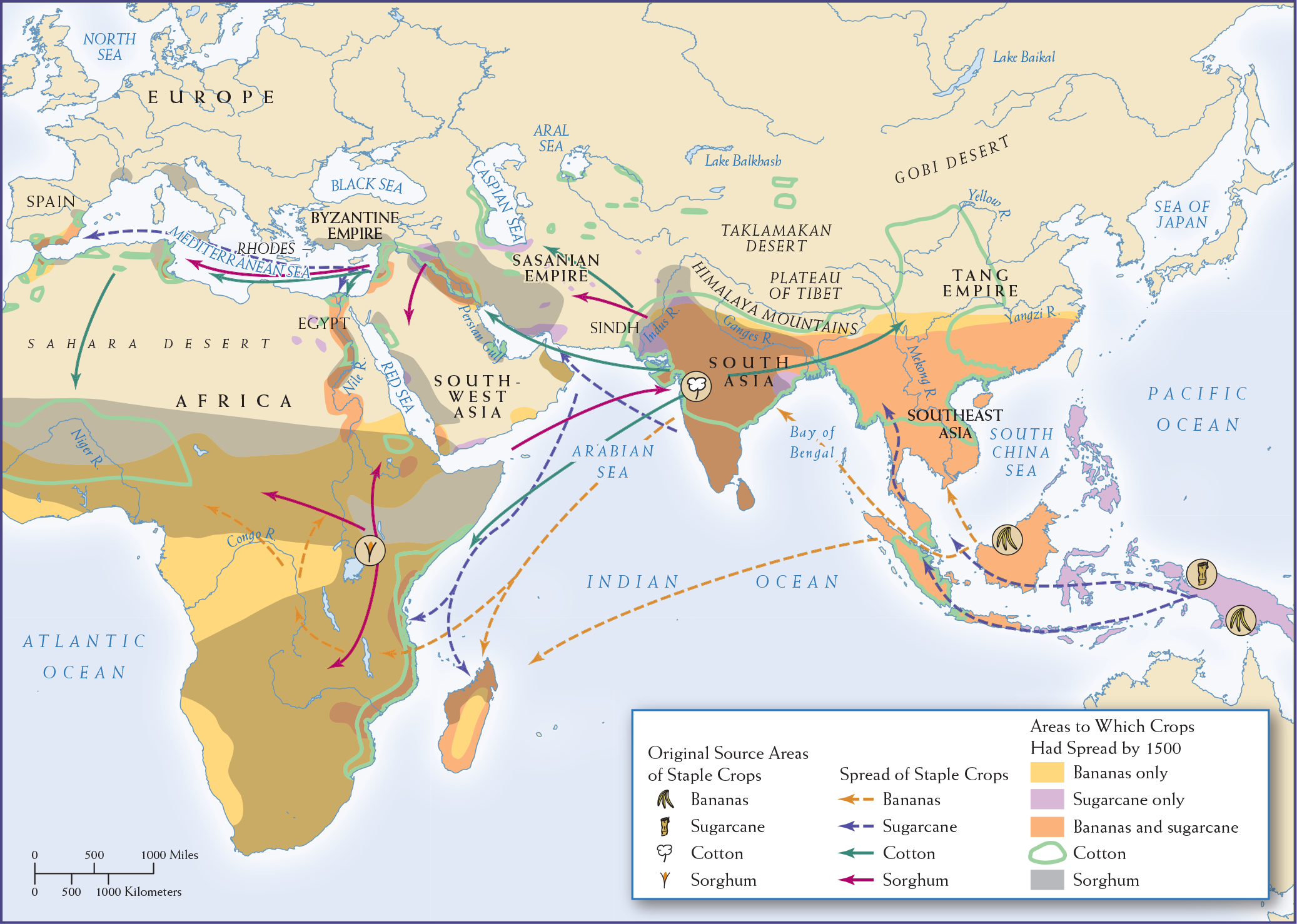

Map 9.4 is titled Agricultural Diffusion in the First Millennium. The map shows source areas of staple crops (bananas, sugarcane, cotton, and sorghum), as well as the routes by which they spread and the areas to which they had spread by 1500. Bananas and sugarcane were originally sourced from Indonesia. Bananas spread from Indonesia to Southeast Asia, South Asia, Madagascar, and Africa. Areas to which banana crops had spread by 1500 included Southeast Asia, India, Mesopotamia, the area around the Nile River, and South-Eastern Africa. Sugarcane spread to Southeast Asia and then from South Asia along with Southwest Asia and the east coast of Africa, as well as west across the Mediterranean. By 1500 sugarcane had spread to the same area of Southeast Asia as bananas but only sugarcane spread east through Indonesia from its source and into the Philippines. Cotton was originally sourced in Northern India. The spread of cotton traveled to the Tang Empire, the Sasanian Empire, through the Persian Coast, and to Africa. Areas to which cotton crops had spread by 1500 included Western and Northern China, parts of present day Indonesia, areas around the Niger River, parts of the Middle East, and South-Eastern Africa. Sorghum was originally sourced in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Mesopotamia region. Sorghum spread toward southern and central Africa, South West Asia, South Asia, and the Sasanian Empire. Areas to which sorghum crops had spread by 1500 included Northern Africa, South West Asia, parts of Europe, parts of the Byzantine and Sasanian Empire, and parts of South Asia.

MAP 9.4 | Agricultural Diffusion in the First Millennium

The second half of the first millennium (500–1000 CE) saw a revolution in agriculture throughout Afro-Eurasia. Agriculturalists across the landmass increasingly cultivated similar crops.

- Where did the staple crops originate? In what direction and where did most of them flow?

- What role did the spread of Islam and the growth of Islamic empires (see Map 9.1) play in the process?

- What role did Southeast Asia and the Tang dynasty play in the spread of these crops?

With a large and professionally trained army capable of defending far-flung frontiers and squelching rebellious populations, the Tang built a military organization of aristocratic cavalry and peasant soldiers. The cavalry regularly clashed on the northern steppes with encroaching nomadic peoples, who also fought on horseback; at its height the Tang military had some 700,000 horses. At the same time, between 1 and 2 million peasant soldiers garrisoned the south and toiled on public works projects.

Much like the Islamic forces, the Tang’s frontier armies increasingly relied on pastoral nomadic soldiers from the Inner Eurasian steppe. Notable were the Uighurs, Turkish-speaking peoples who had moved into western China and by 750 CE constituted the empire’s most potent military force. These hard-riding and hard-drinking warriors galvanized fearsome cavalries, fired longbows at distant range, and wielded steel swords and knives in hand-to-hand combat. The Tang military also pushed the state’s authority into Tibet, the Red River valley in northern Vietnam, Manchuria, and Bohai (near the Korean Peninsula).

By 650 CE, as Islamic armies were moving eastward toward central Asia, the Tang were already the region’s new colossus. At the Tang empire’s height, its armies controlled more than 4 million square miles of territory—an area as large as the entire (by now politically fragmented) Islamic world in the ninth and tenth centuries CE. The Tang benefited from South China’s rich farmlands, brought under peasant cultivation by draining swamps, building an intricate network of canals and channels, and connecting lakes and rivers to the rice lands. The state thereby was able to collect taxes from roughly 10 million families, representing 57 million individuals. Taxes that took the form of agricultural labor propelled the expansion of cultivated frontiers throughout the south.

Despite the Abbasid Empire’s expansion and its rout of Tang forces at the Talas River in 751 CE, which stopped Chinese expansion westward, Tang China in the mid-eighth century CE was still the most powerful, most advanced, and best administered empire in the world. (See Map 9.5.) Korea and Japan recognized its superiority in every material aspect of life. Muslims were among the people who arrived in Chang’an to pay homage to the Tang ruler. Persians, Armenians, and Turks brought tribute and merchandise via the busy arteries of the Silk Roads or by sea, and other travelers and traders came from Southeast Asia, Korea, and Japan. This network of routes was rarely traversed the entire length by a single person, however. It was more a chain of entrepôts than an early version of an interstate.

More information

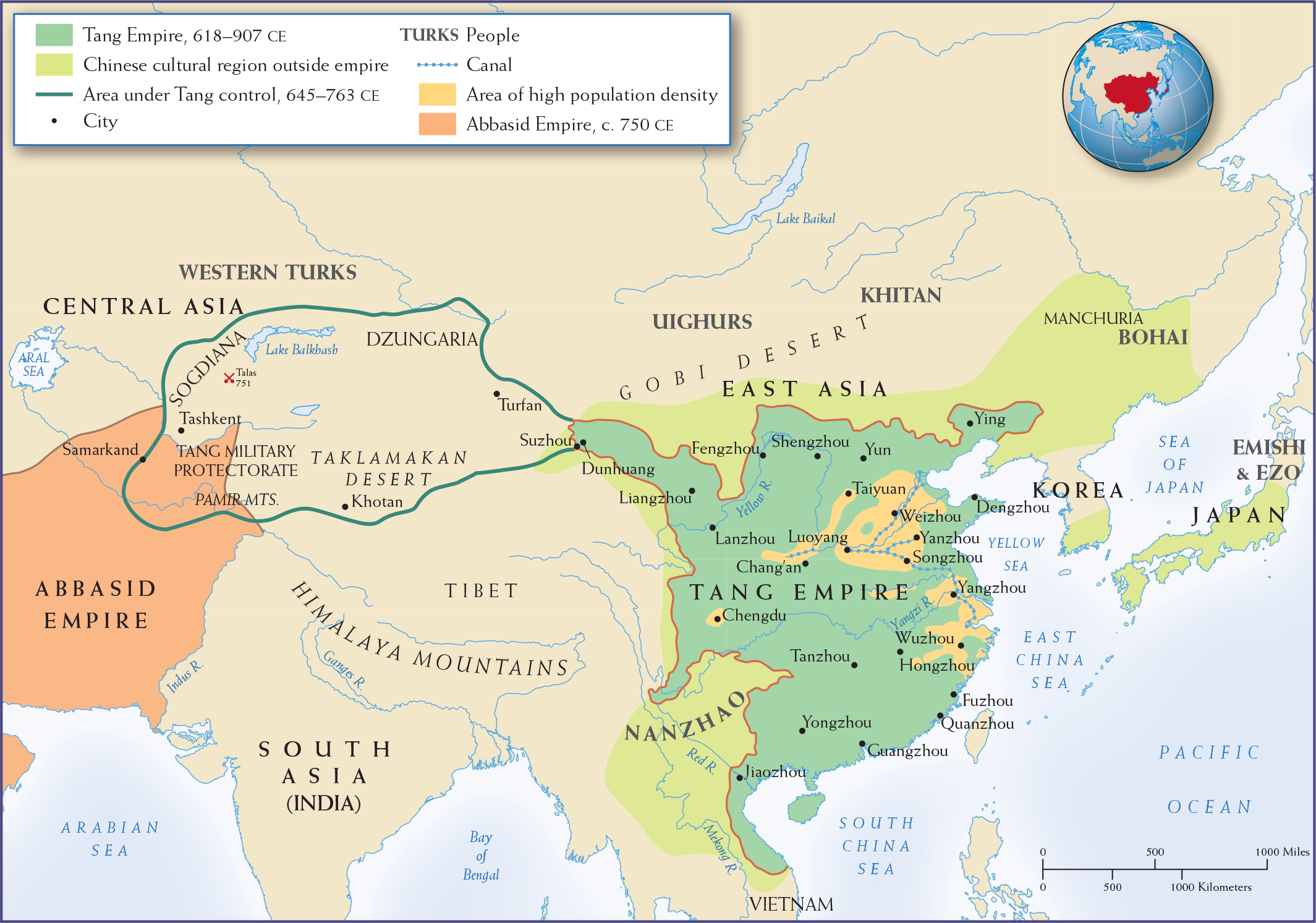

Map 9.5 is titled The Tang State in East Asia, 750 C E. The map shows the Tang Empire (618 to 907 C E), Chinese cultural regions outside the empire, areas under Tang control (645 to 763 C E), and areas of high population density, as well as the extent of the Abbasid Empire circa 750 C E. The Tang Empire, controls most of the Eastern and Central parts of present day China, while the Chinese cultural regions extend farther south and up north to Korea and Japan. The Abbasid Empire circa 750 C E controls present day Iran and Afghanistan. The areas around the Pamir Mountains, Sogdiana, Lake Baikal, Dzungaria, and the Taklamakan Desert are under Tang control. Some Tang control even moved into the northeast corner of the Abbasid Empire. The Western Turks were located in Central Asia, while the Uighurs and Khitan were located north of the Gobi Desert. Emishi and Ezo were located in Japan. Canals were built in the Tang Empire near the east coast of China and areas of high population density.

MAP 9.5 | The Tang State in East Asia, 750 CE

The Tang dynasty, at its territorial peak in 750 CE, controlled a state that extended from central Asia to the East China Sea.

- Which parts of the Tang dynasty benefited from the canal system that had been enhanced by its short-lived predecessor, the Sui?

- How did the area under Tang control change over time? Based on your reading of the chapter and the information on the map, what factors shaped the area controlled by the Tang?

- What foreign areas were under Tang control? What areas were heavily influenced by Tang government and culture?

More information

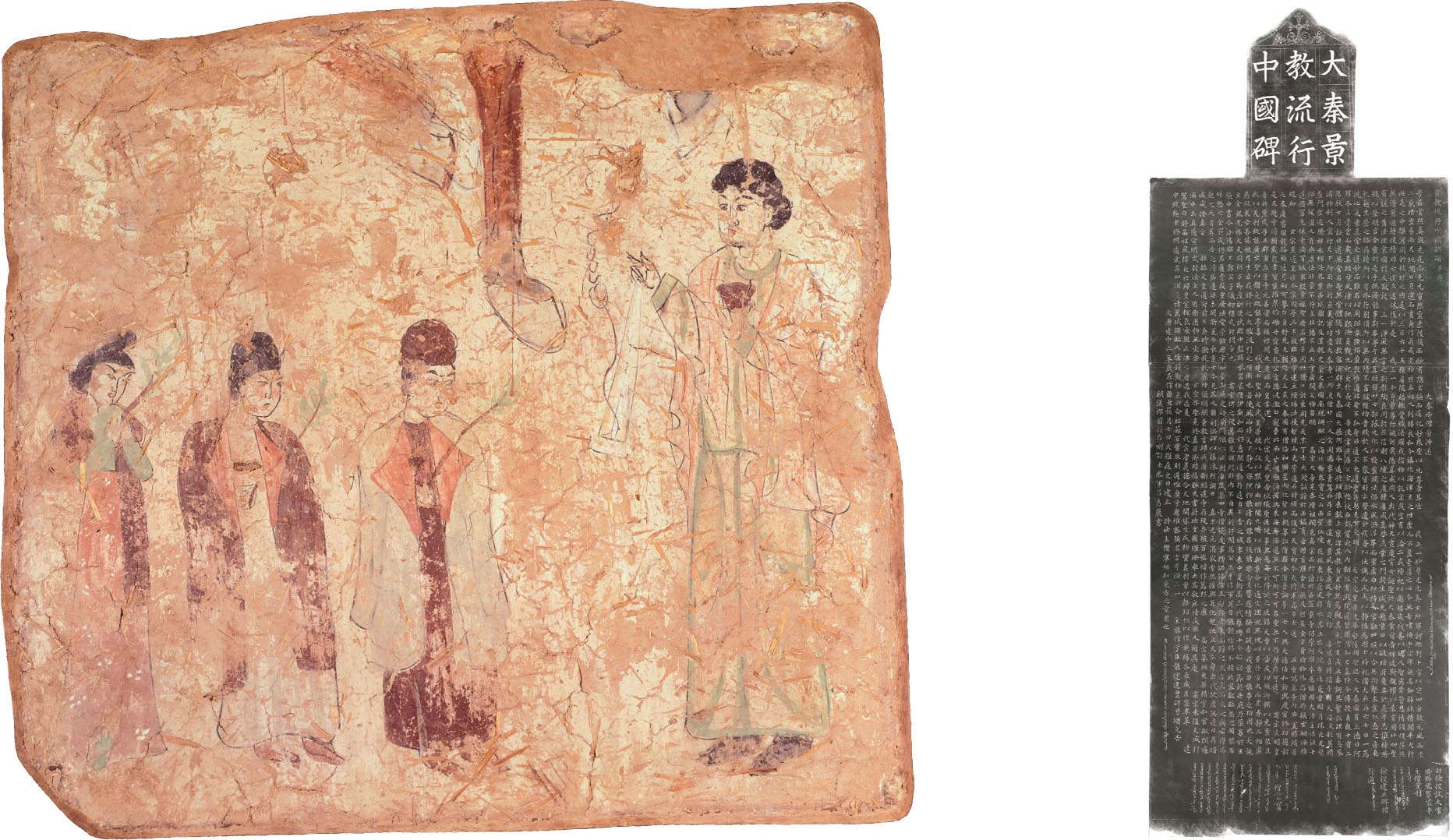

A mural painting shows two men and one woman from the left approaching another man on the right. The man on the right wears a hat and a vestment with a collar reaching to the feet. The other men wear similar headgears and capes. The woman is in traditional Chinese attire. The mural is very faded in many places.

A tall limestone block with text in both Chinese and Syriac.

The peak of Chinese power occurred just as the Abbasids were expanding into Tang portions of central Asia. Rival Muslim forces drove the Tang from Turkistan in 751 CE at the Battle of Talas River, and their success emboldened groups such as the Sogdians and Tibetans to challenge the Tang themselves. As a result, the Tang gradually retreated into the old heartlands along the Yellow and Yangzi Rivers. They even saw their capital fall to invading Tibetans and Sogdians. Thereafter, misrule, court intrigues, economic exploitation, and popular rebellions weakened the empire, even though it held on for over a century more until northern invaders toppled it in 907 CE.

Organizing the Tang Empire

The Tang Empire emulated the Han in many ways, but its rulers also introduced new institutions. The heart of the agrarian-based Tang state was the magnificent capital city of Chang’an, whose population reached 1 million; half of the people lived within its impressive city walls and half lived on the outside. The outer walls enclosed an immense 30-square-mile area. Internal security arrangements made Chang’an one of the safest urban locales for its age. Its more than 100 quarters were separated from each other by interior walls with gates that were closed at night, after which no one was permitted on the streets, which were patrolled by horsemen until the gates reopened in the morning. Chang’an had a large foreign population, estimated at one-third of its total, and a diverse religious life. Zoroastrian fires burned as worshippers sacrificed animals and chanted temple hymns. Nestorian Christians from Syria found a welcoming community, and Buddhists could boast ninety-one of their own temples in Chang’an in 722 CE.

CONFUCIAN ADMINISTRATORS The fruits of agriculture and the day-to-day control of the Tang Empire required an efficient and loyal civil service. Entry into the ruling group required knowledge of Confucian ideas and all the commentaries on the Confucian classics. It also required skill in the intricate classical Chinese language, in which this literature was written.

Reinforcing the bureaucracy of the Tang state were the world’s first fully written civil service examinations, which tested sophisticated literary skills and knowledge of the Confucian classics. The Tang also allowed the use of Daoist classics as texts for the exams, believing that the early Daoists represented another important stream of ancient wisdom. Candidates for office, whom local elites recommended, gathered in the capital triennially to take qualifying exams. They had been trained since the age of three in the classics and histories, either by their families—especially mothers—or in Buddhist temple schools. Most failed the grueling competition, but those who were successful underwent further trials to evaluate their character and determine the level of their appointments. New officials were selected from the pool of graduates based on social conduct, eloquence, skill in calligraphy and mathematics, and legal knowledge.

Although in theory official careers were open to anyone of proven talent, in practice they were closed to certain groups. Women were not permitted to serve, nor were sons of merchants or those who could not afford a classical education. Over time, though, Tang civil examinations forced aristocrats to compete with commoner southern families, whose growing wealth gave them access to educational resources that made them the equals of the old elites. Through examinations, this new elite eventually outdistanced the sons of the northern aristocracy in the Tang government, in effect by out-studying them.

The system underscored education as the primary avenue for success. Even impoverished families sought the best classical education they could afford for their sons. Although few succeeded in the civil examinations, many boys and even some girls learned the fundamentals of reading and writing. Buddhists played a crucial role in extending education across society: as part of their charitable mission, their temple schools introduced many children to primers based on classical texts. Many Buddhist monks, in fact, entered the clergy only after not qualifying for or failing the civil examinations.

CHINA’S FEMALE EMPEROR Not all Tang power brokers were men. As we have seen in many other contexts, the wives and mothers of emperors also wielded influence in the court—usually behind the scenes, but sometimes publicly. The most striking example is the Empress Wu, who dominated the Tang court in the late seventh and early eighth centuries CE. Usually vilified in Chinese accounts, she deftly exploited the examination system to check the power of aristocratic families and consolidated courtly authority by creating groups of loyal bureaucrats, who in turn preserved loyalty to the dynasty at the local level.

Born into a noble family, Wu Zhao played music and mastered the Chinese classics as a young girl. Because she was witty, intelligent, and beautiful, she was recruited by age thirteen to Emperor Li Shimin’s court and became his favorite concubine. She also fell in love with his son. When Li Shimin died, his son assumed power and became Emperor Gaozong. Wu became the new emperor’s favorite concubine and gave birth to the sons he required to succeed him. As the mother of the future emperor, Wu enjoyed heightened political power. Using her position, she strategized to take the place of Gaozong’s empress, Wang, by accusing her of killing Wu’s newborn daughter. Emperor Gaozong believed his favorite concubine, Wu, and married her. Following Gaozong’s death, Wu Zhao made herself Empress Wu (r. 684–705 CE). She expanded the military and recruited her administrators from the civil examination candidates to oppose her enemies at court.

More information

A painting of Empress Wu Zhao wearing a an elaborate headdress and a garment with floral designs. There are three dots on her forehead between the eyebrows.

More information

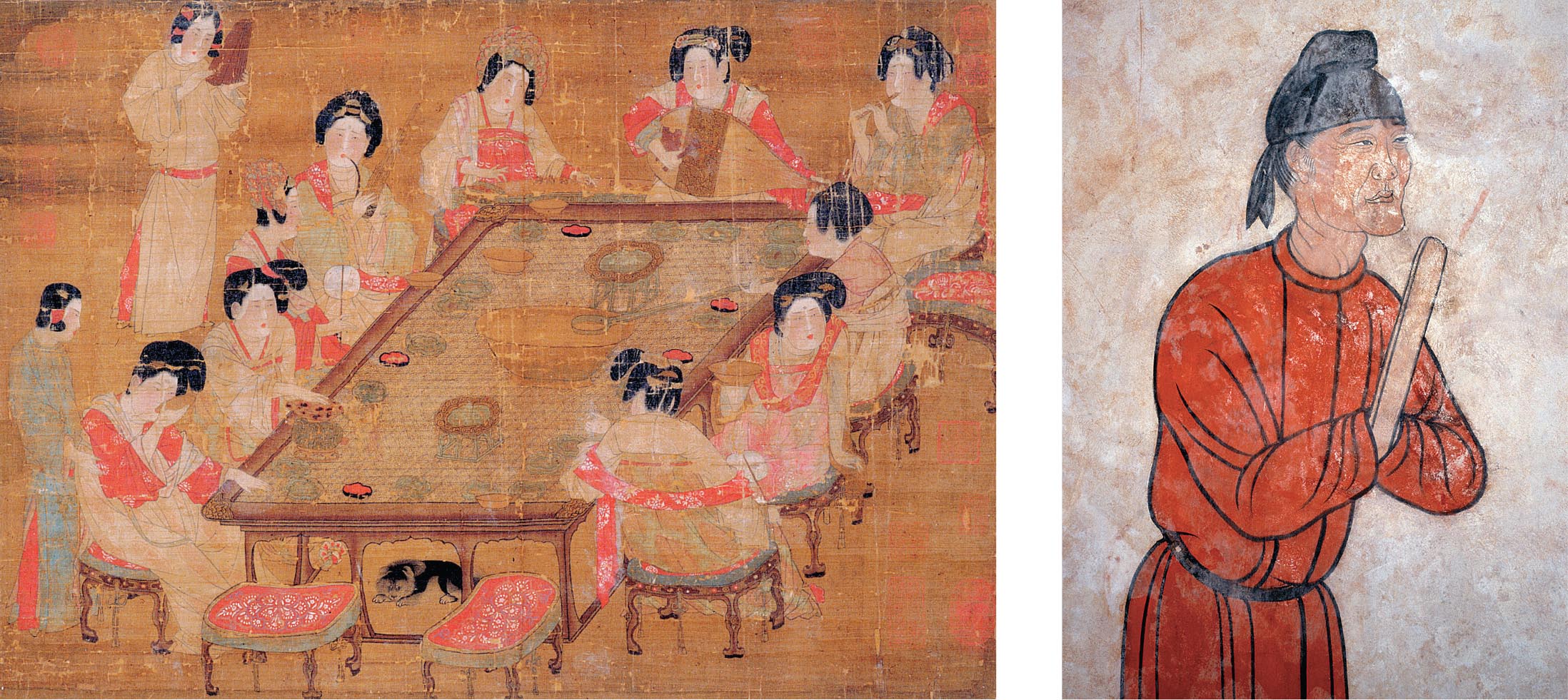

A painting of several women sitting around a large rectangular table eating, talking with one another, and playing music. Three woman sit at the far end of the table playing instruments and several of the other women at the table hold bowls. Two women stand to the left of the table and a small dog sits beneath the table.

A painting of a eunuch wearing traditional robes and holding up a long piece of wood.

Wu ordered scholars to write biographies of famous women, and she empowered her mother’s clan by assigning high political posts to her relatives. Later, she moved her court from Chang’an to Luoyang, where she tried to establish a new “Zhou dynasty,” seeking to imitate the widely admired era of Confucius. Empress Wu elevated Buddhism over Daoism as the favored state religion, invited the most gifted Buddhist scholars to her capital at Luoyang, built Buddhist temples, and subsidized spectacular cave sculptures. In fact, Chinese Buddhism achieved its highest officially sponsored development in this period.

EUNUCHS Tang rulers protected themselves, their possessions, and especially their women with loyal and well-compensated men, many of whom were eunuchs (surgically castrated as youths and thus sexually impotent). By the late eighth century CE, more than 4,500 eunuchs were entrenched in the Tang Empire’s institutions, wielding significant power not only within the imperial household but also at court and beyond.

The Chief Eunuch controlled the military. Through him, the military power of court eunuchs extended to every province and garrison station in the empire, forming an all-encompassing network. In effect, the eunuch bureaucracy mediated between the emperor and the provincial governments.

Under Emperor Xianzong (r. 805-820 CE), eunuchs acted as a third pillar of the government, working alongside the official bureaucracy and the imperial court. By establishing clear career patterns for eunuchs that paralleled those in the civil service, Xianzong sparked a striking rise in their levels of literacy and their cultural attainments. And yet, they remained the rivals of most officials. By 838 CE, the delicate balance of power between throne, eunuchs, and civil officials had evaporated. Eunuchs became an unruly political force in late Tang politics, and their competition for influence produced political instability.

An Economic Revolution

At its height, Tang China’s economic achievements included agricultural production based on an egalitarian land allotment system, an increasingly fine handicrafts industry, a diverse commodity market, and a dynamic urban life. The earlier short-lived Sui dynasty had started this economic progress by reunifying China and building canals, especially the Grand Canal linking the north and south. The Tang continued by centering their efforts on the Grand Canal and the Yangzi River, which flows from west to east. These waterways aided communication and transport throughout the empire. The south grew richer, largely through the backbreaking labor of immigrants from the north. Fertile land along the Yangzi became China’s new granary, and areas south of the Yangzi became its demographic center.

GREEN REVOLUTION IN TANG CHINA The same agricultural revolution that was sweeping through South Asia and the Islamic world also took East Asia by storm. China received the same crops that Muslim cultivators were carrying westward. Rice was critical. New varieties entered from the south, and groups migrating from the north (after the collapse of the Han Empire) eagerly took them up. Soon Chinese farmers became the world’s most intensive wet-field rice cultivators. Early- and late-ripening seeds supported two or three plantings a year. Champa rice, introduced from central Vietnam, was especially popular for its drought resistance and rapid ripening.

Because rice needs ample water, Chinese hydraulic engineers went into the fields to design water-lifting devices, which peasant farmers used to construct hillside rice paddies. This new rice cultivation was also the partial impetus for the canal building already mentioned. Engineers dug canals linking rivers and lakes, and they even drained swamps, alleviating the malaria that had long troubled the region. Their efforts yielded a booming and constantly moving rice frontier.

TRADE IN LUXURIES Chinese merchants took full advantage of the Silk Roads to trade with India and the Islamic world; when rebellions in northwest China and the spread of Islamic rule into central Asia jeopardized the land route, the “silk road by the sea” became the avenue of choice. From all over Asia and Africa, merchant ships arrived in South China ports bearing spices, medicines, and jewelry in exchange for Chinese silks and porcelains. In the large cities of the Yangzi delta, workshops produced rich brocades (silk fabrics), fine paper, intricate woodblock prints, unique iron casts, and exquisite porcelains. Art collectors across Afro-Eurasia especially valued Tang “tricolor pottery,” decorated with brilliant hues. Chinese artisans transformed locally grown cotton into highest-quality clothing. Painting and dyeing technology improved, and the resulting superb silk products generated significant tax revenue. These Chinese luxuries dominated the trading networks that reached Southwest Asia, Europe, and Africa via the Silk Roads and the Indian Ocean.

Managing Religious Diversity in China

The early Tang emperors tolerated remarkable religious diversity. Nestorian Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Manichaeanism (a syncretic Christian sect) had entered China from Persia during the time of the Sasanian Empire. Islam came just after. These spiritual impulses—together with Buddhism and the indigenous teachings of Daoism and Confucianism—spread throughout the Tang Empire and were skillfully wielded to enhance state power during the more tolerant early phase of the dynasty’s rule.

More information

A photo of the monastery on Mount Song. The view of the monastery features several small stone towers that are scattered about. Several trees are visible amidst the towers. In the background behind the towers are mountains.

THE GROWTH OF BUDDHISM Buddhism, in particular, thrived under Tang rule. Initially, Emperor Li Shimin distrusted Buddhist monks because they avoided serving the government and paying taxes. Yet after Buddhism gained acceptance as one of the “three ways” of learning—joining Daoism and Confucianism—Li endowed huge monasteries, sent emissaries to India to collect texts and relics, and commissioned Buddhist paintings and statuary. Caves along the Silk Roads, such as those at Dunhuang, provided ideal venues for monks to paint the inside walls where religious rites and meditation took place. Soon the caves boasted bright color paintings and massive statues of the Buddha and the bodhisattvas.

ANTI-BUDDHIST CAMPAIGNS By the mid-ninth century CE, however, the growing influence of China’s hundreds of thousands of Buddhist monks and nuns started to threaten Confucian and Daoist leaders, who responded by arguing that Buddhism’s values conflicted with indigenous traditions. One Confucian-trained scholar-official, Han Yu, even attacked Buddhism as a foreign doctrine of barbarian peoples who were different in language, culture, and knowledge from the Chinese. Although Han Yu was exiled for his objections, two decades later the state began suppressing Buddhist monasteries and confiscating their wealth, fearing that religious loyalties would undermine political ones. Increasingly intolerant Confucian scholar-administrators argued that the Buddhist monastic establishment threatened the imperial order.

Piecemeal measures against the monastic orders gave way in the 840s CE to open persecution. Emperor Wuzong, for instance, closed more than 4,600 Buddhist monasteries and destroyed 40,000 temples and shrines. More than 260,000 Buddhist monks and nuns endured a forced return to secular life, after which the state parceled out monastery lands to taxpaying landlords and peasant farmers. To expunge the cultural impact of Buddhism, classically trained literati revived ancient prose styles and the teachings of Confucius and his followers. Linking classical scholarship, ancient literature, and Confucian morality, they constructed a cultural fortress that reversed the early Buddhist successes in China.

Ultimately, the Tang era represented the triumph of homegrown ideologies (Confucianism and Daoism) over a foreign universalizing religion (Buddhism). In addition, by permanently breaking apart huge monastic holdings, the Tang made sure that no religion would rival its power. Successor dynasties continued to keep religious establishments weak and fragmented, although Confucianism maintained a more prominent role within society as the basis of the ruling classes’ ideology and as a quasi-religious belief system for a wider portion of the population. As a result, within China religious pluralism survived, even including Buddhism, which continued to be important in the face of dynastic persecution.

The Fall of Tang China

The Tang dynasty’s downfall was ultimately due to economic reasons, not religious challenges. Deteriorating economic conditions in the ninth century CE led to peasant uprisings, some headed by unsuccessful examination candidates. These revolts eventually brought down the Tang dynasty. Power-hungry eunuchs also contributed to the demise of the Tang, as did pressures from Muslim incursions into the western regions of the Tang Empire and Sogdian and Tibetan pressures in the northwest. By the tenth century CE, China had fragmented into regional states and entered a new but much shorter era of decentralization. The Song dynasty that emerged in 960 CE could not unify the Tang territories, and even the Mongols, invading steppe peoples, were able to restore the glory of the Han and Tang Empires only for a century.

Early Korea and Japan

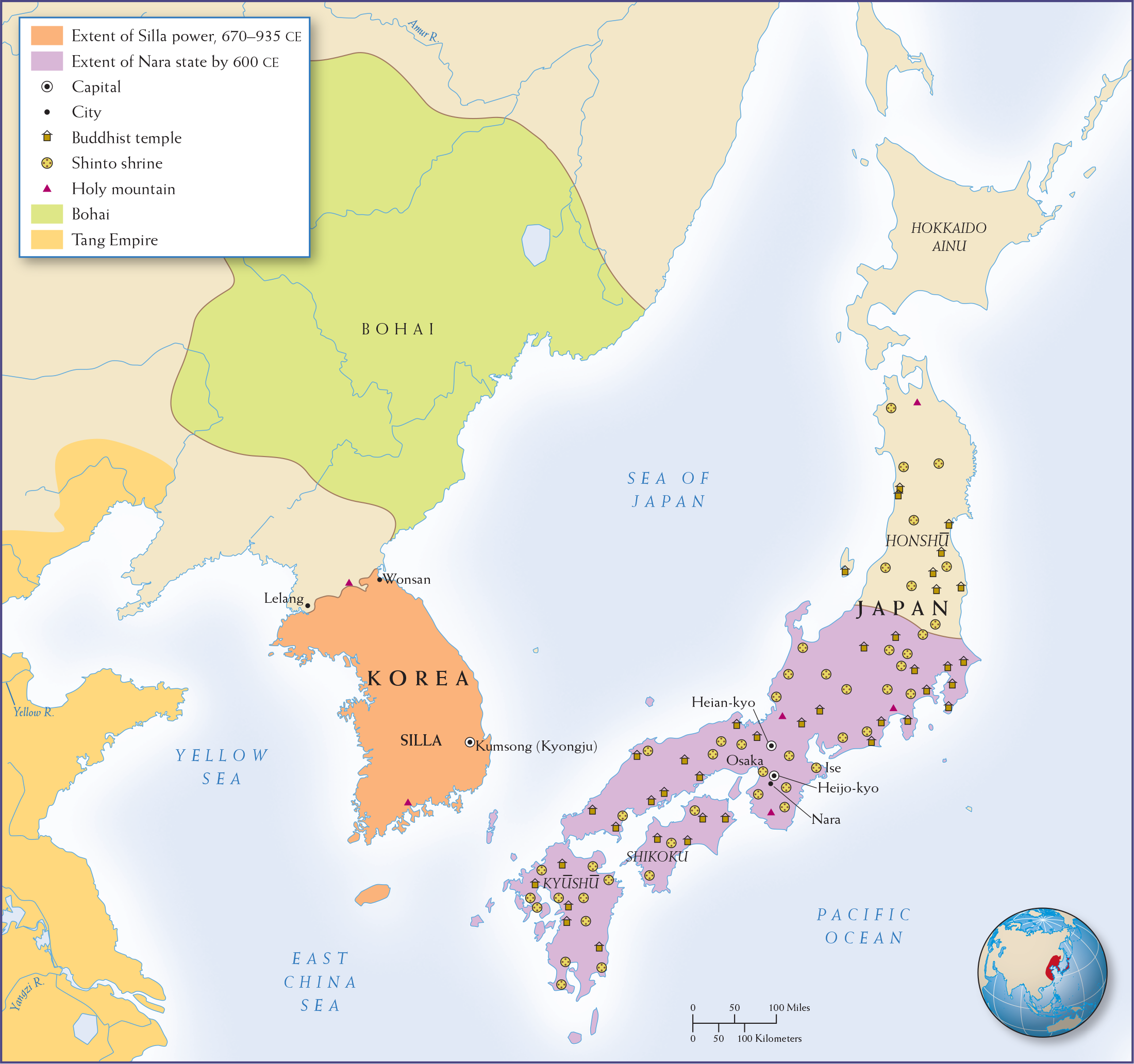

Chinese influence, both direct and indirect, had reached into Korea for more than a millennium and later into Japan, but not without local resistance; it did not impede the flourishing of entirely indigenous and independent political and religious developments. (See Map 9.6.) Here, too, religion contributed to the strengthening of the political power of elites, and lively commercial exchanges brought new prosperity to large segments of the population. The decline of Tang power in central Asia after 750 CE caused Chinese rulers and merchants to look toward Southeast Asia and other parts of East Asia to compensate for their losses, including the lands of the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan. Buddhism also spread into these territories, bringing with it a more flexible and less distinctly Chinese influence, although Confucianism also proved well tailored to the needs of Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

EARLY KOREA By the fourth century CE, three independent states had emerged on the Korean Peninsula. Chinese influence had increasingly penetrated the peninsula and had become a decisive element in Korean history from at least the third century BCE. Korea remained divided into “Three Kingdoms” until 668 CE, when one of these states, Silla, led a movement to prevent Chinese domination, gaining control over the entire peninsula and unifying it.

Unification under the Silla enabled Koreans to establish an autonomous government. Their opposition to the Chinese did not deter them from modeling their government on the Tang imperial state. The Silla rulers dispatched annual emissaries bearing tribute payments to the Chinese capital and regularly sent students and monks. As a result, the written language of Korean elites became literary Chinese—not their own vernacular (just as Latin did among diverse populations in medieval Europe). Chinese influence convinced the Silla state to organize its court and the bureaucracy and to build its capital city of Kumsong in imitation of the Tang capital of Chang’an.

More information

Map 9.6 is titled Tang Borderlands: Korea and Japan, 600 to 1000 C E. The map shows the extent of Silla power (670 to 935 C E) and the Nara state by 600 C E, along with the locations of Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, Holy mountains, capitals, cities, the area of Bohai control, and the Tang Empire. The Nara State takes up the southern half of present day Japan and is full of Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. The capitals are Heian-Kyo and Heijo-Kyo. Other cities included are Nara and Osaka. There are three holy mountains located in the Nara state. The Honshu region is not a part of the Nara state but has Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines throughout. The Silla power consists of the southern roughly 75 percent of present day Korea. There are no temples or shrines but two holy mountains: one at the northern portion of Silla and the other at the bottom. The capital is Kumsong (Kyongju). Other cities include Wonsan. The Bohai is located north of Korea, while the Tang Empire occupies the eastern edge of China.

MAP 9.6 | Tang Borderlands: Korea and Japan, 600–1000 CE

The Tang dynasty held great power over emerging Korean and Japanese states, although it never directly ruled either region.

- Based on the map, what connections do you see between Korea and Japan and the Tang Empire?

- What, if any, relationship do you see between the proliferation of Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines?

Despite Chinese influences, the loyalty of most non-Chinese Koreans was to their kinship groups. These early Koreans believed that birth, not displays of learned achievement, should determine how much influence one had in religious and political life. Korean holy men and women (known today as shamans) interceded with gods, demons, and ancestral spirits and were prominent in local village life.

Silla’s fortunes were entwined with the Tang’s to such an extent that once the Tang declined, Silla also began to fragment. But Silla never established a full-blown Tang-style government. That would happen later under the Koryo dynasty (935–1392 CE).

The Koryo dynasty (from which the country’s modern name derives) began to construct a new cultural identity by enacting a bureaucratic system, which replaced the archaic tribal system that the Silla had maintained. The Koryo went beyond earlier Silla reforms and fully used Tang-style civil service examinations for selecting semiofficial military elites who would govern at court and in the provinces. The heirs of Wang Kon, who founded the dynasty, consolidated control over the peninsula and strengthened its political and economic foundations by following the Tang’s bureaucratic and land allotment systems.

During this period, Korea, like Tang China itself, suffered continual harassment from northern tribes such as the Khitan. To escape the realities of this troubled period, Koryo artisans anxiously carved wooden printing blocks drawn from the Buddhist literary works as an offering to the Buddha to protect them from invading enemies—but in vain. The Korean royal family at the time was constantly under siege, and they hoped that the woodblocks would elicit a change in fortune. The scriptures were hidden away in a single temple and when rediscovered represented the most comprehensive and intact version of Buddhist literature written in the Chinese script.

More information

A photo of the main hall of a temple. It is a three-story structure that has roofs that overhang out for each floor. The top of the building has a small triangular shape on top of the uppermost overhang. A small staircase goes up to the entrance. A smaller two story tower is visible in the background to the left.

A fresco of the Yakushi Buddha features him sitting with several figures on either side of him. His head is framed with several concentric circles. Winged beings fly above the human figures. Much of the fresco is faded.

EARLY JAPAN Like Korea, Japan also felt pressure from China, and it responded by thwarting some Tang influences and accommodating others simultaneously. But Japan enjoyed greater autonomy than Korea: it was an archipelago of islands, separated from the mainland by water, though also internally fragmented. In the mid-third century CE, a warlike group arrived by sea from Korea and imposed its military and social power on southern Japan. These conquerors—known as the “Tomb Culture” because of their elevated burial sites—unified Japan by introducing a new form of ancestor worship that would have long-lasting effects. They also introduced a belief in the power of female shamans, who married into the imperial clans and became rulers of early Japanese kinship groups.

Chinese dynastic records describe the early Japanese, with whom imperial China had contact in this period, as a “dwarf” people who maintained a rice and fishing economy. Japanese farmers also mastered Chinese-style sericulture: the production of raw silk by raising silkworms.

THE YAMATO EMPERORS AND SHINTO ORIGINS OF THE JAPANESE SACRED IDENTITY In time, the complex aristocratic society that developed within the Tomb Culture gave rise to a Japanese state on the Yamato plain in the region now known as Nara, south of Osaka. In becoming the ruling faction in this area, the Yamato clan incorporated native Japanese as well as Korean migrants. Clan leaders also elevated their own belief system that featured ancestor worship into a national religion known as Shinto. (Shinto means “the way of the deities.”) Shinto beliefs derived from the early Japanese groups and held that after death a person’s soul (or spirit) became a Shinto kami, or local deity, provided that it was nourished and purified through proper rituals and festivals. Before the imperial Yamato clan became dominant, each clan had its own ancestral deities, but after 500 CE all Japanese increasingly worshipped the Yamato ancestors, whose origins went back to the fourth-century CE Tomb Culture. Other regional ancestral deities were later subordinated to the Yamato deities, who claimed direct lineage from the primary Shinto deity Amaterasu, the sun goddess and creator of the sacred islands of Japan.

After 587 CE, the Soga kinship group—originally from Korea but by 500 CE a minor branch of the Yamato imperial family—became Japan’s leading family and controlled the Japanese court through intermarriage. Soon, they were attributing their cultural innovations to their own Prince Shotoku (574–622 CE), a direct descendant of the Soga and thus of the Yamato imperial family as well.

Contemporary Japanese scribes claimed that Prince Shotoku, rather than Korean immigrants, introduced Buddhism to Japan and that his illustrious reign sparked Japan’s rise as an exceptional island kingdom. Shotoku promoted both Buddhism and Confucianism, thus enabling Japan, like its neighbor early Tang China, to be accommodating to numerous religions. Although earlier Korean immigrants had laid the groundwork for the development of these views, Shotoku was credited with assimilating these faiths into the native religious culture, Shinto. The prince also had ties with several Buddhist temples modeled on Tang pagodas and halls; one of these, in Nara (Japan’s first imperial capital), is Horyuji Temple, the oldest surviving wooden structure in the world. Its frescoes include figures derived from the art of Iran and central Asia. They are a reminder that within two centuries Buddhism had dispersed its visual culture along the full length of the Silk Roads—from Afghanistan to China and then on to Korea and the island kingdom of Japan.

Political integration under Prince Shotoku did not mean political stability, however. In 645 CE, the Nakatomi clan seized the throne and eliminated the Soga and their allies. Via intermarriage with imperial kin, the Nakatomi became the new spokespeople for the Yamato tradition. Thereafter, clan leader Nakatomi no Kamatari (614–669 CE) enacted a series of reforms, known as the Taika Reforms, which reflected Confucian principles of government allegedly enunciated by Shotoku. These reforms enhanced the power of the ruler, no longer portrayed simply as an ancestral kinship group leader but now depicted as an exalted “emperor” (tenno) who ruled by the mandate of heaven, as in China, and exercised absolute authority.

Diverse religious currents continued to flow into Japan, contributing to a climate of spiritual pluralism that helped bolster the authority of the Yamato rulers. Although Prince Shotoku and later Japanese emperors turned to Confucian models for government, they also dabbled in occult arts and Daoist purification rituals. In addition, the Taika edicts promoted Buddhism as the state religion of Japan. Although the imperial family continued to support native Shinto traditions, association with Buddhism gave the Japanese state extra status by lending it the prestige of a universalizing religion whose appeal stretched to Korea, China, and India.

State-sponsored spiritual diversity led native Shinto cults to formalize a creed of their own. Indeed, the introduction of Confucianism and Buddhism motivated Shinto adherents to assemble their diverse religious practices into a well-organized belief system to compete for followers. Shinto priests now collected ancient liturgies, and Shinto rituals (such as purification rites to ward off demons and impurities) gained recognition in the official Department of Religion.

Although the Japanese welcomed the Buddhist faith, they did not fully accept the traditional Buddhist view that the state was merely a vehicle to propagate moral and social justice for the ruler and his subjects. Instead, the Japanese saw their emperor (the embodiment of the state) as an object of worship, a sacred ruler, one in a line of luminous Shinto gods, a supreme kami—a divine force in his own right. Thus, Buddhism as imported from China and Korea changed in Japan to serve the interests of the state (much as Christianity served the interests of European monarchs and Islam served Muslim dynasties).

Glossary

- civil service examinations

- Set of challenging exams instituted by the Tang to help assess potential bureaucrats’ literary skill and knowledge of the Confucian classics.

- eunuchs

- Surgically castrated men who rose to high levels of military, political, and personal power in several empires (for instance, the Tang and the Ming Empires in China; the Abbasid and Ottoman Empires; and the Byzantine Empire).