Alubabaz, the Elephant

The Formation of European Christendom

Historians debate whether or not to label this period in Europe “the Dark Ages.” Scholars who have spurned the term “Dark Ages,” in favor of the term “Late Antiquity,” emphasize the political and cultural continuities between Rome and its successor states, especially in the eastern Mediterranean, and the new dynamic institutions that arose in Rome’s wake. (See Current Trends in World History: The Origins of Islam in the Late Antique Period: A Historiographical Breakthrough.) Scholars who favor the term “Dark Ages” stress what they see as a sharp cultural, political, and economic decline accompanying the Roman Empire’s fall, especially in the western Mediterranean. “The Dark Ages,” as a label for this period, has been resurrected by some environmental historians, who argue that the period was indeed dark, as a result of a colder and drier climate. Agricultural production declined, famines occurred year after year, and infectious diseases spread across Afro-Eurasia (for example, the plague during the reign of Justinian; see Chapter 8). This harsher climate and the diseases that accompanied it between 400 and 900 CE caused mortality on a large scale. The drought that was wreaking havoc in Europe is the same one that may have helped spur Arab tribal peoples, carrying the banner of Islam, to pour out of their severely affected lands in the Arabian Peninsula in search of better lands and a better life.

Although western Europe lacked a highly developed political empire like that of the Umayyads, the Abbasids, or the Tang dynasty, Christianity increasingly unified the peoples of Europe. In the fifth century CE, the mighty Roman military machine gave way to a multitude of warrior leaders whose principal allegiances were local affiliations. The political ideal of the Roman Empire cast a vast shadow over western Europeans, but it was a spiritual institution that inherited the mantle of Rome: the Roman Catholic Church. The church’s powerful head, the pope, was based in Rome, and its universalizing agents—missionaries and monks—carried its message far and wide. (See Map 9.7.) In eastern Europe and Byzantium, a form of Christianity known as Greek Orthodoxy had become dominant by 1000 CE. Together, these two major strands of the faith—the western Roman Catholic Church and eastern Greek Orthodoxy—constituted the realm of Christendom, the entire portion of the world in which Christianity prevailed as a unifying institution. “Christendom,” and not “Europe,” was the name used by the inhabitants of these areas, where illiteracy was the norm and geographic knowledge was exceedingly rare.

Charlemagne’s Fledgling Empire

Far removed from the old centers of high culture, Charlemagne (r. 768–814 CE), ruler of the Franks in northern Europe, expanded his western European kingdom through constant warfare and plunder. In 802 CE, Harun al-Rashid, the Abbasid ruler of Baghdad, sent the gift of an elephant to Charlemagne, already the king of the Franks for three decades and recently crowned by the pope in Rome as “Holy Roman Emperor” (on Christmas Day in 800 CE). The elephant caused a sensation among the Franks, who saw the gift as an acknowledgment of Charlemagne’s power. In fact, al-Rashid often sent rare beasts to distant rulers as a gracious reminder of his own formidable power. In his eyes, Charlemagne’s “empire” was a minor principality.

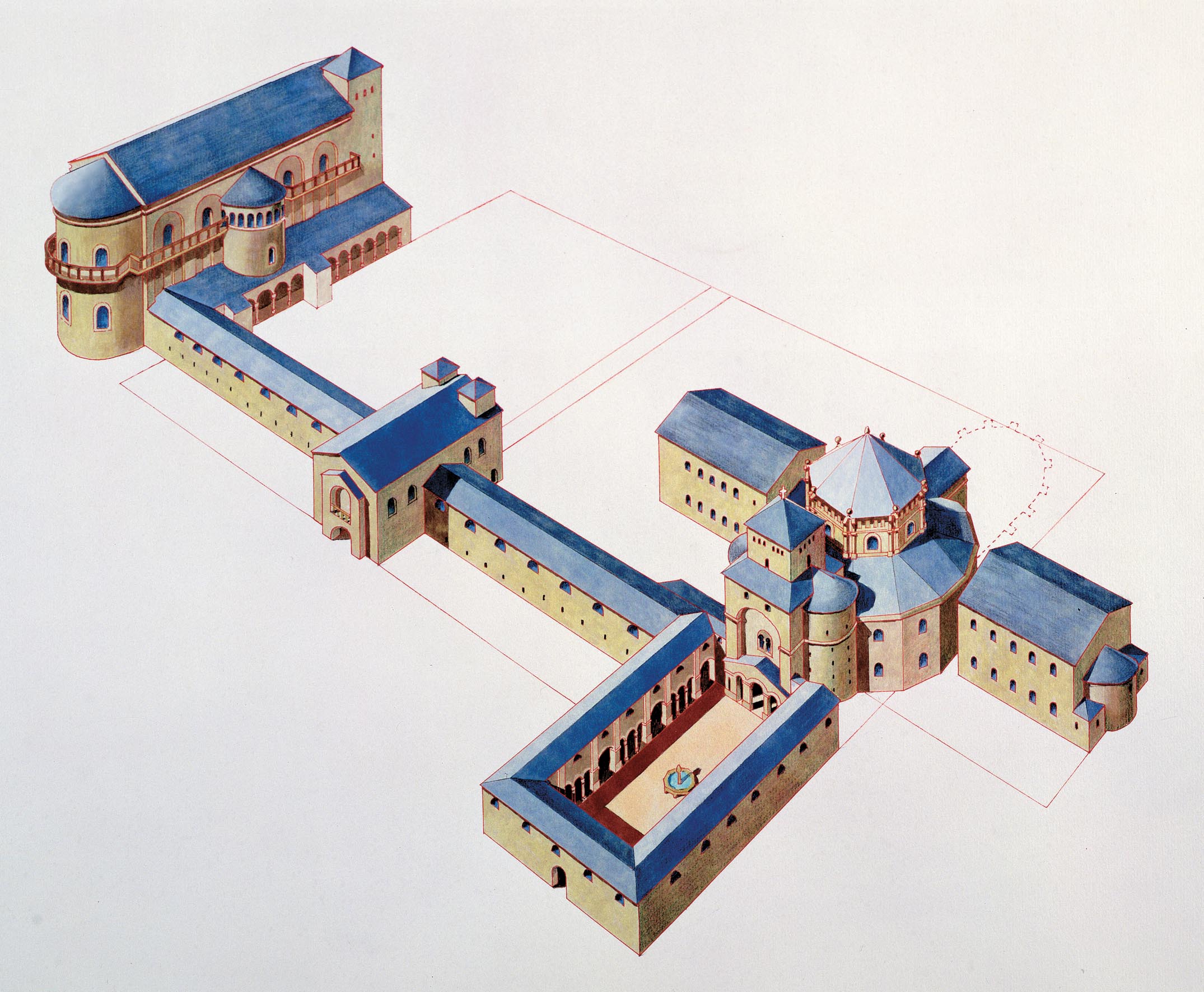

Charlemagne’s empire had a population of less than 15 million; he rarely commanded armies with more than 5,000 soldiers and his tax system was rudimentary. At a time when the caliph’s palace at Baghdad covered nearly 250 acres, Charlemagne’s palace at Aachen was merely 330 by 655 feet. Baghdad itself was almost 40 square miles in area, whereas there was no “town” outside the palace at Aachen. The palace was essentially a large country house set in open countryside, where Charlemagne and his Franks hunted wild boar on horseback. Still, courtly life in the so-called Holy Roman Empire (which in fact was neither very holy, nor Roman, nor much of an empire) was animated by Charlemagne’s many wives, concubines, and offspring. Perhaps surprisingly for medieval Christendom, his daughters played an important role in the social life of the court but also its politics. They advised their father on policy, accompanied him in public appearances, and even controlled access to him. One historian of the time complained of a “monstrous regiment of women” being in charge of the empire. Charlemagne is said to have so loved his daughters that he never allowed them to marry. More realistic observers have noted that a shrewd ruler like Charlemagne would have gone to great lengths to avoid dividing his property up into dowries for his daughters or exposing himself to political challenges from a son-in-law. Whatever the reason, he was adamant in his refusal to have them wed. When one of his sons was set to marry a daughter of King Offa of Mercia (England), Offa suddenly insisted that Charlemagne offer his daughter Bertha for marriage to one of Offa’s sons to complete the exchange of heirs. Charlemagne grew so enraged that not only did he cancel the original wedding, he also barred all English merchants from trading in his domains. We would be mistaken, however, to assume that Charlemagne’s patriarchal stance backed by an even more patriarchal church resulted in chaste, modest lives for his daughters. In fact, they seem to have enjoyed great personal freedom along with their considerable political influence; their multiple lovers and illegitimate children had free reign in court, at least until their father died and they were sent off to monasteries or simply disappeared from the historical record.

Charlemagne and his men were representatives of the warrior class that dominated post-Roman western Europe. For a time, Roman rule had imposed an alien way of life in this rough world. After that empire faded, however, war became once again the duty and pastime of the landowners. Buoyed up by their chieftains’ mead—a heavy beer made from honey—young men eagerly followed their lords into battle.

And although the Franks vigorously engaged in trade, that trade was likewise based on war. In fact, Europe’s principal export at this time was Europeans, and the massive sale of prisoners of war financed the Frankish Empire. From Venice, which grew rich from its role as middleman, captives were enslaved and sent across the sea to Alexandria, Tunis, and southern Spain. The main victims of this trade were Slavic-speaking peoples, tribal hunters and cultivators from eastern Europe. It is this trade that gave us our modern—and troubled—term slave (from Slav) for persons bought and sold as items of merchandise.

More information

Map 9.7 is titled Christendom, 600 to 1000 C E. The map shows the extent of Catholic Christianity; Orthodox Christianity; Charlemagne’s kingdom at the beginning of his rule, as well as his empire circa 814 C E; and the path of missionaries, cities, and important churches and monasteries. Catholic Christianity encompasses most of south and central Europe and as far north as the present day United Kingdom, Iceland, southern parts of Sweden and Norway, and the northern portions of Portugal and Spain. Orthodox Christianity encompasses most of South-Eastern Europe (present day Greece and Macedonia), as well as most of west and central present day Turkey. Missionaries travel from Iraq to Central Asia. Another missionary route goes from Alexandria down the Nile River. Another missionary route travels from Constantinople to Armenia, across the Black Sea, and toward Europe. Another missionary route travels from Italy to eastern and western Europe, and from the Frankish Kingdom to Ireland and Scotland. Churches and monasteries are shown throughout, with particular density in Egypt, Italy, and France. Charlemagne’s kingdom begins in France, while his empire expands to include Germany, other parts of Central Europe, and Italy.

MAP 9.7 | Christendom, 600–1000 CE

The end of the first millennium saw much of Europe divided between two versions of Christianity, each with different traditions. On the map, locate Rome and Constantinople, the two seats of power in Christianity.

- According to the map, what were the two major regions where Christianity held sway? In what directions did Roman Catholic Christianity and Greek Orthodox Christianity spread?

- Where were important churches and monasteries heavily concentrated? Why do you think they were concentrated in those regions?

- The map suggests that missionaries played important roles in spreading Roman Catholicism and Greek Orthodoxy. Why do you think this was the case?

More information

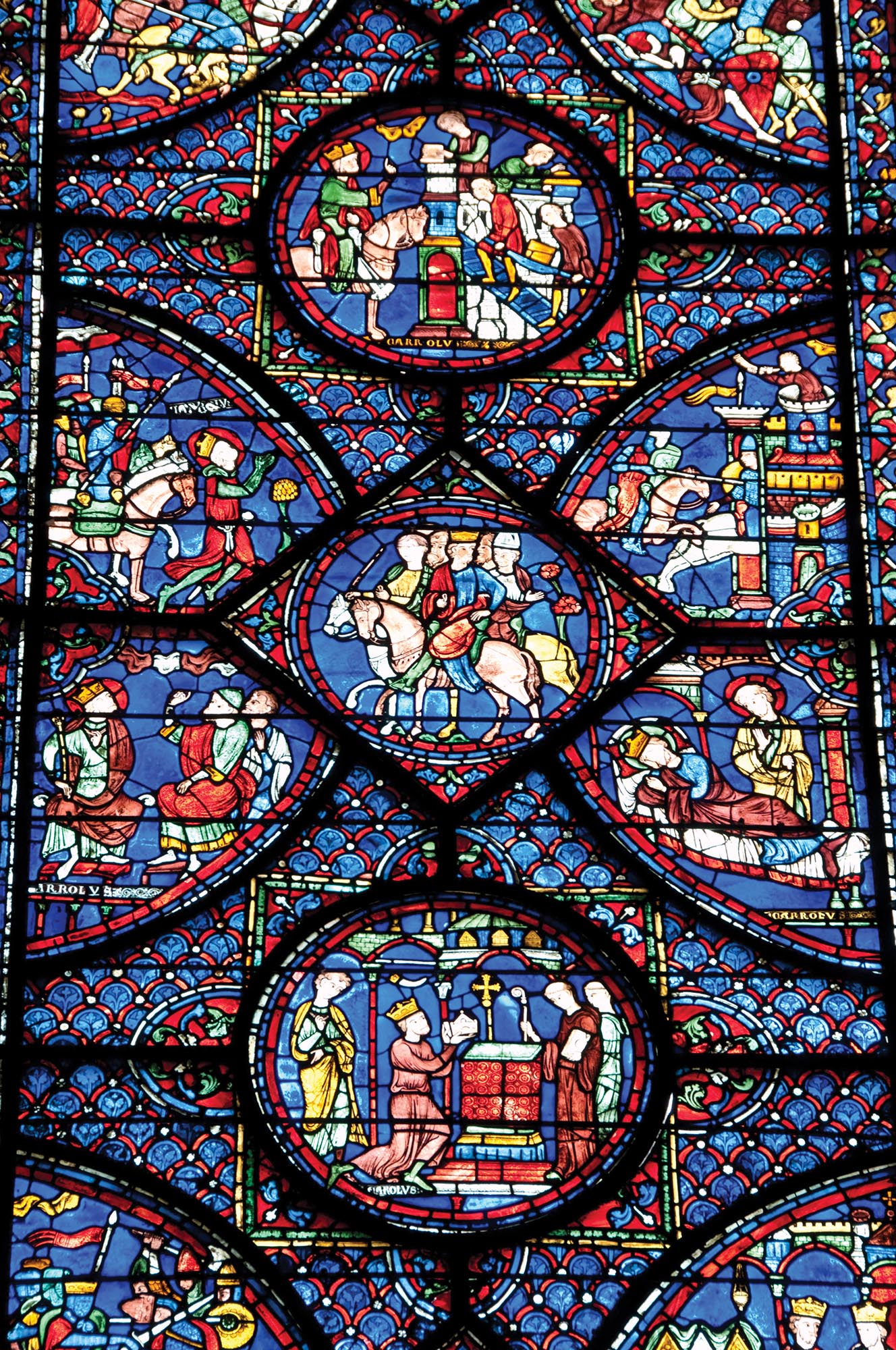

A colorful stained glass window that depicts several scenes from the life of Charlemagne. The center three scenes from top to bottom show Charlemagne on a horse facing a person on top of a small building and two people walking up the stairs of the building while carrying an object between them, Charlemagne and several other people on horseback, and Charlemagne kneeling in front of a dais while offering up an object to two people behind the dais as another person watches from behind. On the left are scenes of Charlemagne on his knees looking up at the sky while people on horseback stand behind him and Charlemagne sitting facing two other people while looking up. On the right are scenes of Charlemagne riding on horseback in front of a castle with a person in top in a tower and Charlemagne lying in bed while a figure stands over him.

Yet this seemingly uncivilized and inhospitable zone offered fertile ground for Christianity to sink roots. Although its worldwide expansion did not occur for centuries, its spiritual conquest of European peoples established institutions and fired enthusiasms that would later drive believers to carry its message to faraway lands.

Christianity in Western Europe

Christians of the west, including those in northern Europe, felt that theirs was the one truly universal religion. Their goal was to bring rival groups into a single Roman “catholic” (from the Greek for “universal”) church that was replacing a political unity lost in western Europe when the Roman Empire fell. Drawing on Augustine of Hippo’s centuries-old ideas (c. 410 CE), the western Christians believed that the “city of God” would take earthly shape in the form of a catholic church, and that this catholic church was not just for Romans—it was for all times and for all peoples.

More information

A drawing of Charlemagne’s Palace and Chapel. The Palace is a large several-story rectangle that is connected to the main chapel by a covered walkway. The Chapel is a large circular structure that has a large domed ceiling. The Chapel is flanked by two rectangular buildings on each side. In the front is a large open courtyard.

The arrival of Christianity in northern Europe provoked a cultural revolution. Preliterate societies now encountered a sacred text—the Bible—in a language that seemed utterly strange. Latin had become a sacred language, and books themselves were vehicles of the holy. The bound codex (see Chapter 8), which had replaced the clumsy scroll, was still a messy object. It had no divisions between words, no punctuation, no paragraphs, no chapter headings. Readers who knew Latin as a spoken language could understand the script. But the Irish, Saxons, and Franks could not, for they had never spoken Latin. Consequently, manuscript copyists in the newly Christian north lavished great care on the few parchment texts—like the Gospels in the Book of Kells (c. 800 CE)—that were prepared with words separated, sentences correctly punctuated and introduced by uppercase letters, and chapter headings marked.

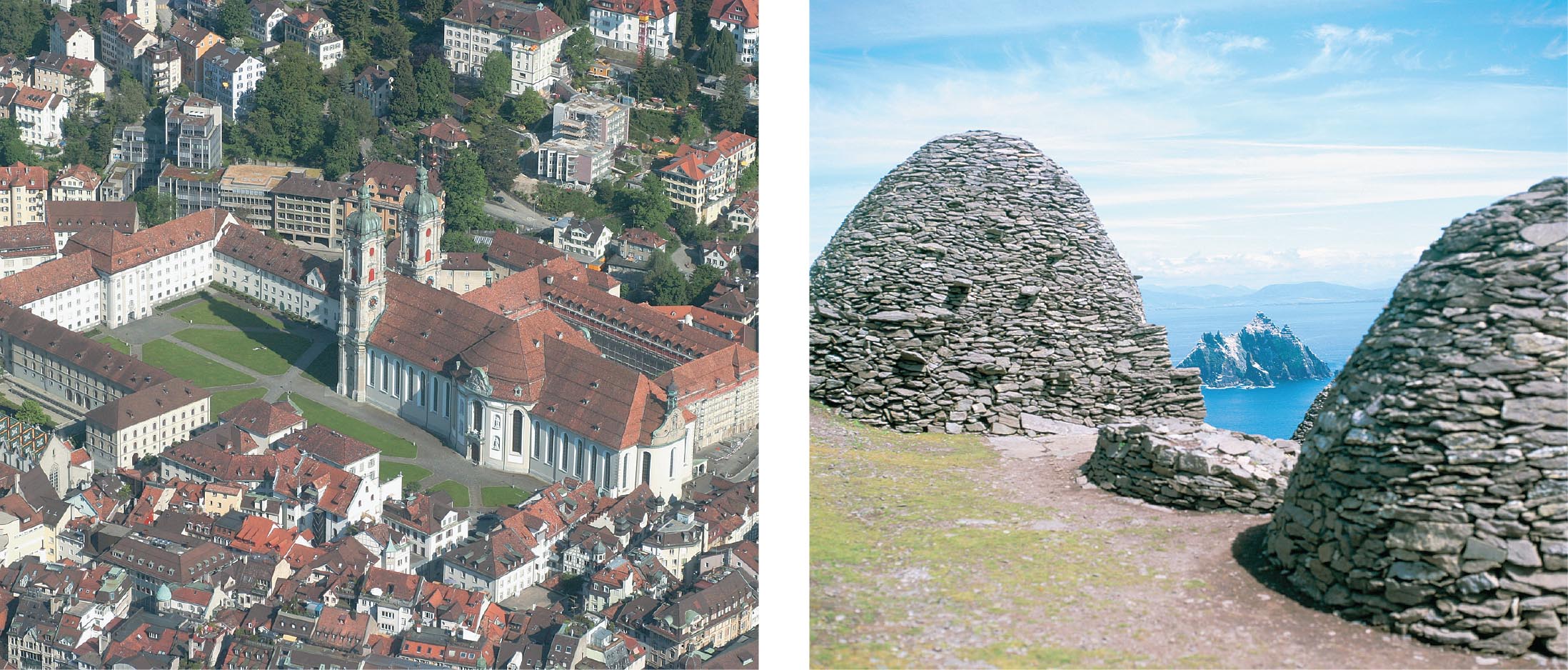

Those producing these stunning Bibles were starkly different from ordinary women and men. They were nuns and monks. Christian monasticism had originated in Egypt, but it suited the missionary tendencies of Christianity in northern Europe particularly well. The root of “monastic” and “monk” is the Greek monos, “alone”: a monastic was a woman or man who chose to live alone, without the support of marriage or family. Monasticism placed small groups of women and men in the middle of societies with which they had nothing in common. It appealed to a deep sense that the very women and men who had little in common with “normal” people were best suited to mediate between believers and God. Laypersons (common believers, not clergy) gave gifts to the monasteries and offered them protection. In return, they gained the prayers of nuns and monks and the reassurance that although they themselves were warriors and men of blood, the nuns’ and monks’ intercessions would keep them from going to hell. Payment for human sin, the atoning power of Jesus’s crucifixion, and the efficacy of monastic prayers were significant theological emphases for Roman Catholics.

More information

A page from Celtic Bible shows swirling circular and orthogonal patterns.

NUNS, MONKS, AND POPES With the spread of monasticism, Christianity in the west took a decisive turn. In Muslim (as in Jewish) societies, religious leaders did not hold formal positions in the mosque or synagogue, as neither religion maintained a clergy. Those who led prayer were essentially no different from others in their communities: they were simply more learned and thus provided their knowledge as required. Accordingly, most rabbis, Muslim scholars, jurists, and mystics were married men, just like laymen; some were even merchants and courtiers. In the Christian west, the opposite was true: warrior societies honored small groups of women and men (the nuns and monks) who were utterly unlike themselves: celibate, unmarried, unfit for warfare, and intensely literate in an incomprehensible tongue. Even their hair looked different. Monks, unlike warriors, were close-shaven; by contrast, the Orthodox clergy of the Eastern Roman Empire grew long, silvery beards (signifying wisdom and maturity, not, as in the west, the warrior’s masculine strength). Catholic monks and priests shaved their heads as well as their faces, and nuns covered their heads entirely.

The Catholic Church of northern Europe owed its missionary zeal to the same principles that explained the spread of Buddhism: it was a religion of monks, whose communities represented an otherworldly alternative to the warrior societies of the time. By 800 CE, most regions of northern Europe held great monasteries, many of which were far larger than the local villages. Supported by thousands of serfs, donated by kings and local warlords, the monasteries became powerhouses of prayer that kept the regions safe. Northern Christianity also gained new ties to an old center: the city of Rome. The Christian bishop of Rome had always enjoyed much prestige. But being only one bishop among many, he often took second place to his peers in Alexandria, Antioch, and Constantinople. Though people spoke of him with respect as pope, many others shared that title.

By the ninth century CE, this picture had changed. Believers from the distant north saw only one papa left in western Europe: Rome’s pope. The papacy as we know it arose because of the fervor with which the Catholic Church of western Europe united behind one symbolic center, represented by the popes in Rome and the desire of new Christians in northern borderlands to find a religious leader for their hopes.

Charlemagne recognized this desire very well. In 800 CE, he went out of his way to celebrate Christmas Day by visiting the shrine of Saint Peter in Rome. There, Pope Leo III acclaimed him as the new “emperor” of the west. The ceremony ratified the aspirations of an age. A “modern” Rome—inhabited by popes, famous for shrines of the martyrs, and protected by a “modern” Christian monarch from the north—was what Charlemagne’s subjects wanted.

More information

A bird’s eye view photo of the Saint Gallen Monastery. The monastery is a large central building that is several stories high and has two large towers and a central courtyard. Many smaller but similarly colored buildings sprawl in front of and behind the monastery.

Two dome-shaped stone buildings made of stones. There is a smaller pile of stones in between the two domes The ocean is visible in the background and a large rock juts out of it.

Vikings and Christendom

The Vikings

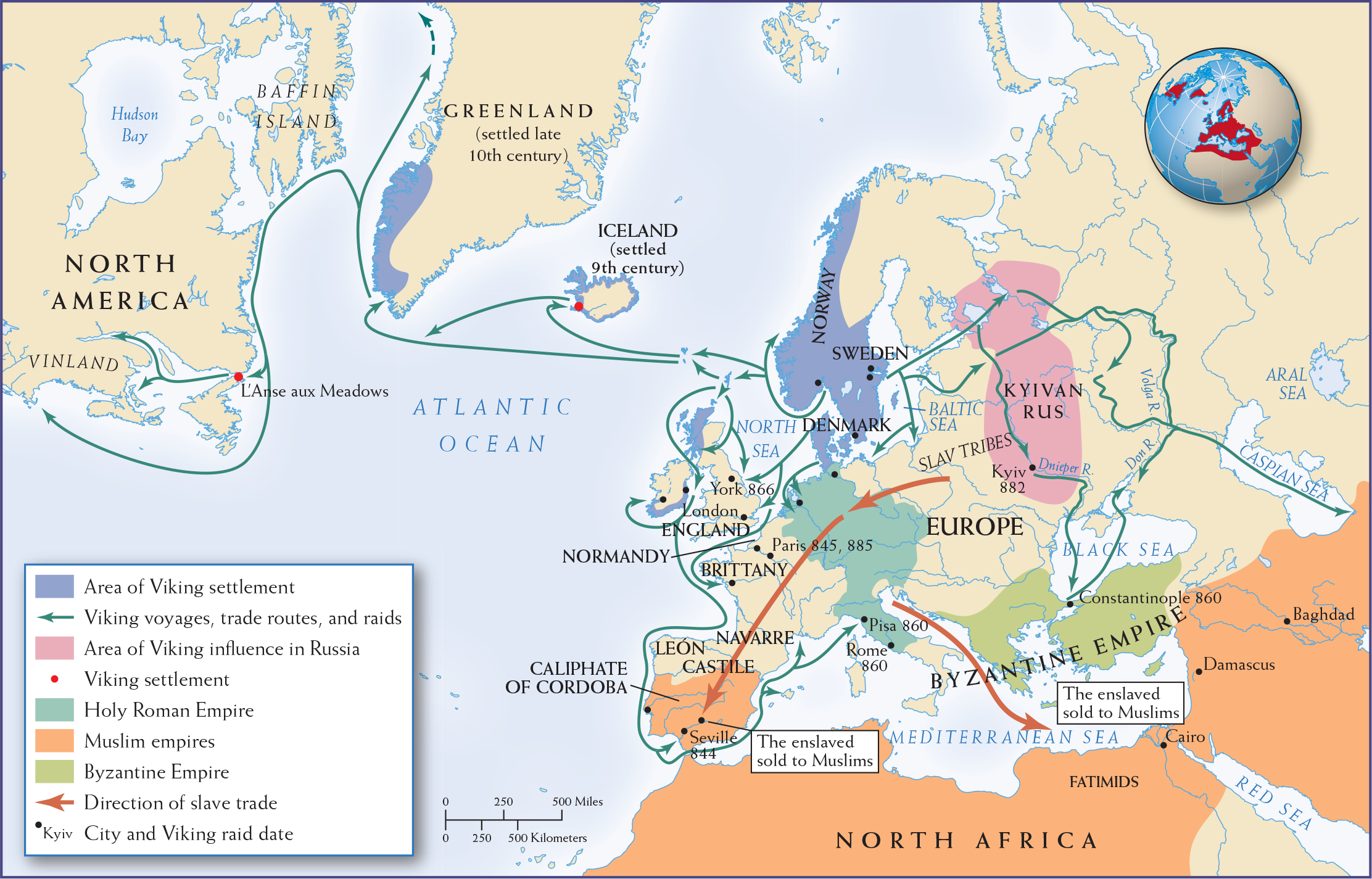

Vikings from Scandinavia exposed the weakness of Charlemagne’s Christian empire. When al-Rashid’s elephant died in 813 CE, one year before Charlemagne himself, the Franks viewed the elephant’s death as an omen of coming disasters. The great beast keeled over when his handlers marched him out to confront a Viking army from Denmark. In the next half century, Charlemagne’s empire of borderland peoples met its match on the widest border of all: that between the European landmass and the mighty Atlantic. (See Map 9.8.)

The Vikings’ motives were announced in their name, which derives from the Old Norse vik, “to be on the warpath.” The Vikings sought to loot the now-wealthy Franks and replace them as the dominant warrior class of northern Europe. It was their turn to extract plunder and to sell droves of the enslaved across the water. They succeeded because of a deadly technological advantage: ships of unparalleled sophistication, developed by Scandinavian sailors in the Baltic Sea and the long fjords of Norway. Light and agile, with a shallow draft, these ships could penetrate far up the rivers of northern Europe and even be carried overland from one river system to another. Under sail, the same boats could tackle open water and cross the unexplored wastes of the North Atlantic.

In the ninth century CE, the Vikings set their ships on both courses. They emptied northern Europe of its treasure, sacking the great monasteries along the coasts of Ireland and Britain and overlooking the Rhine and the Seine—rivers that led into the heart of Charlemagne’s empire. At the same time, Norwegian adventurers colonized the uninhabited island of Iceland, and then Greenland. By 982 CE, they had even reached North America and established a settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows on the Labrador coast. Recent aerial reconnaissance suggests a second Viking settlement in Canada roughly 300 miles south of L’Anse aux Meadows. Viking goods have been found as far west as the Inuit settlements of Baffin Island to the north of Hudson Bay, carried there along trading routes by Indigenous people.

The consequences of this spectacular reach across the ocean to North America were short-lived, but the penetration of eastern Europe had lasting effects. Supremely well equipped to traverse long river systems, the Vikings sailed east along the Baltic and then turned south, edging up the rivers that cross the watershed of central Russia. Here the Dnieper, the Don, and the Volga Rivers flow south into the Black Sea and the Caspian. By opening this link between the Baltic and what is now Kyiv in modern Ukraine, the Vikings created an avenue of commerce that linked Scandinavia and the Baltic directly to Constantinople and Baghdad. And they added yet more enslaved people to transregional commerce: Muslim geographers bluntly called this route “the Highway of the Slaves.”

On reaching the Black Sea, the Vikings made straight for Constantinople. In 860 CE, more than 200 Viking longships gathered ominously in the straits of the Bosporus, beneath the walls of Constantinople. What they found was not Charlemagne’s rustic Aachen but a proud city with a population exceeding 100,000 surrounded by well-engineered late Roman walls.

More information

Map 9.8 is titled The Age of Vikings and the Slave Trade, 800 to 1000 C E. The map includes areas of Viking settlement, Viking influence in Russia, Muslim empires, the Byzantine Empire, the Holy Roman Empire, Viking trade routes, voyages, and raids, and the direction of the slave trade. Viking settlements are found in the western and southern portions of present day Sweden and Norway, as well as Iceland and a small coastline in Scotland, Ireland, and southwest Greenland. The Vikings travel all across Europe using the inland rivers and sailing in the waterways that go around the coastline, raiding York, London, Seville, Rome, Pisa, Paris, Kiev, and Constantinople. The Vikings also travel west to North America across the Atlantic Ocean. The area under Viking influence is in the Eastern part of Europe on the present day border between Russia and Europe. The Byzantine Empire controls present day Greece, Macedonia, and Turkey. The Muslim Empires control virtually all those portions of North Africa and the Middle East shown on the map. Slave routes travel from Europe to the Caliphate of Cordoba, as well as from the Holy Roman Empire (Germany and northern Italy) across the Mediterranean Sea towards Cairo.

MAP 9.8 | The Age of Vikings and the Slave Trade, 800–1000 CE

Vikings from Scandinavia dramatically altered the history of Christendom.

- In what directions did the Vikings carry out their voyages, trade routes, and raids?

- What were the geographical limits of the Viking explorations in each direction?

- In what direction did the slave trade move, and what role did the Vikings and the Holy Roman Emperors play in expanding it?

The Vikings had come up against a state hardened by battle. For two centuries the empire of “East Rome,” centered in Constantinople, had held Muslim armies at bay. From 640 to 840 CE, it faced almost yearly campaigns launched by the caliphs of Damascus and Baghdad, powerhouses that grew to be ten times greater than their own. For years on end, Muslim armies and navies came within striking distance of Constantinople. Each time they failed, outmaneuvered by highly professional generals and blocked by a skillfully constructed line of fortresses that controlled the roads across Anatolia. The Christian empire of East Rome (Byzantium) fought the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad to a draw. The Viking fleet was even less suited to assault Constantinople, as the empire of East Rome had a deadly technological advantage in naval warfare: Greek fire, a combination of petroleum and potassium that, when sprayed from siphons, would explode in a great sheet of flame on the water. A previous emperor had used it to destroy the Muslim fleet as it lay at anchor within sight of Constantinople. Now, a century and a half later, the experience and weaponry of East Rome were too much for the Vikings, and their raid was a spectacular failure. Despite their inability to take Byzantium, the Vikings left an indelible mark on the world through their forays across the North Atlantic, their brutal interactions with Christian communities in northern Europe, and their expansion into eastern Europe, especially the slave trade they facilitated there.

More information

A wooden Viking ship is displayed in a museum. The ship is long and thin at the edges and bows out wide in the middle. A curling circle decorates the tops of the each tall end of the ship. A rod sticks out in the middle of the ship to be used for a sail.

Greek Orthodox Christianity

Withstanding so many military assaults bolstered the morale of the eastern Christians and led to a flowering of Christianity in this region where Europe and Asia meet. Not just Constantinople but Justinian’s glorious church, Hagia Sophia—its heart—had survived. That great building and the solemn Greek liturgy that reverberated within its domed spaces symbolized the branch of Christianity that dominated the east: Greek Orthodoxy. Greek Orthodox theology held that Jesus became human less to atone for humanity’s sins, as emphasized in Roman Catholicism, and more to facilitate theosis, a transformation of humans into divine beings. This was a truly distinct message from that which predominated in the Roman Catholicism of the west.

In the tenth century CE, as Charlemagne’s empire collapsed in western Europe, large areas of eastern Europe became Greek Orthodox, not Catholic. As a result, Greek Christianity gained a broad-based spiritual empire. The conversion of Russian peoples and Balkan Slavs to Greek Orthodox Christianity was a complex process. It reflected a deep admiration for Constantinople on the part of Russians, Bulgarians, and other Slavs. It was an admiration as intense as that of any western Catholic for the Roman popes. This admiration amounted to awe, as shown by the famous story of the conversion to Greek Christianity of the rulers of Kyiv (descendants of Vikings). Unimpressed by the religious practice and structures of Catholic Franks, these Slavic Christians were overwhelmed by what to their eyes was the almost heavenly splendor of the churches they encountered in Greece and Constantinople.

More information

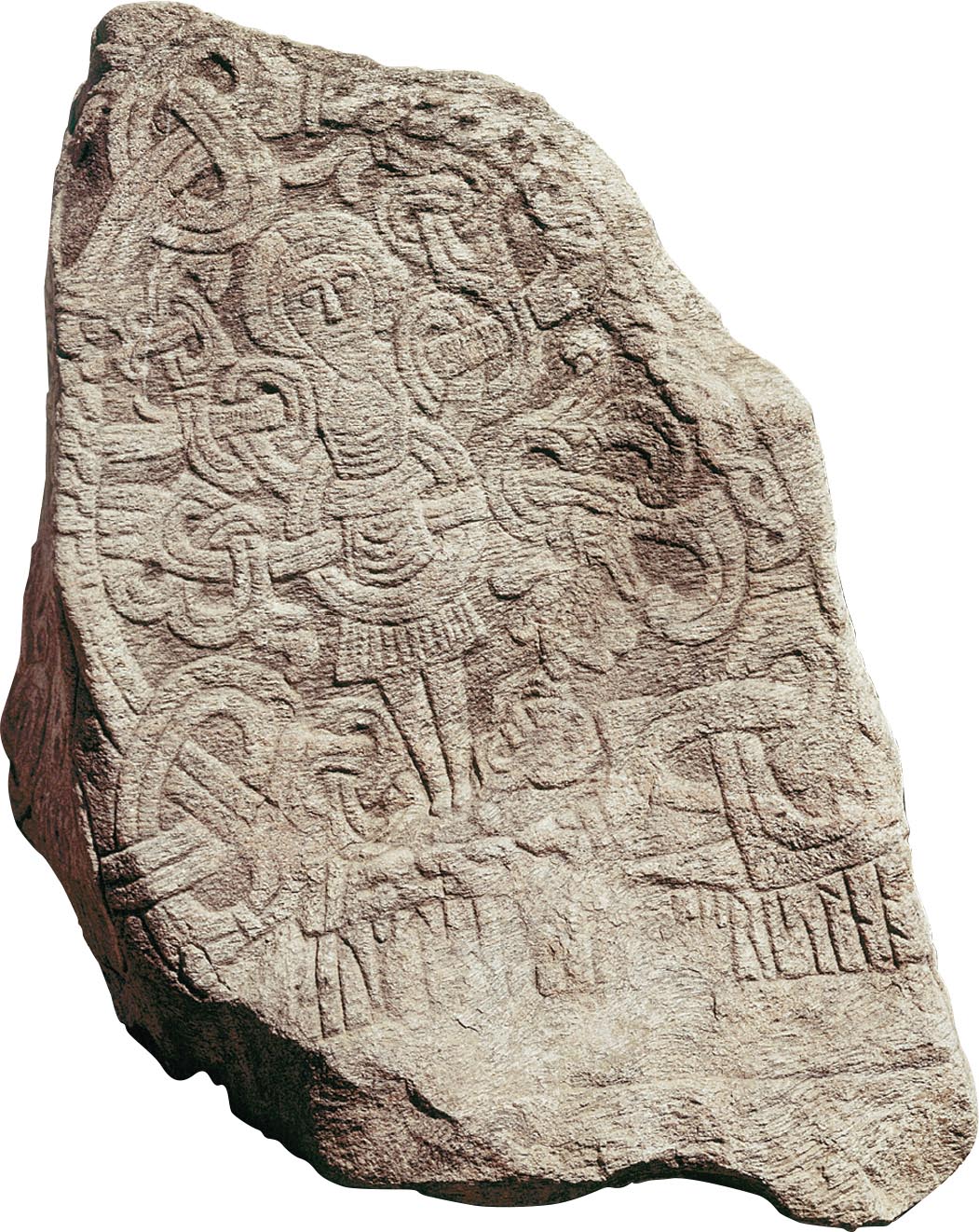

A jelling stone that has a carving of Christ on it. He is entangled in an intricate pattern of lines.

By the year 1000 CE, there were two Christianities: the new and confident “borderland” Roman Catholicism of western Europe and an ancient Greek Orthodoxy, protected against extinction by the iron framework of a “Roman” state inherited from Constantine and Justinian. Roman Catholics believed that their church was destined to expand everywhere. Greek Orthodox Christians were less euphoric but believed that their church would forever survive the regular ravages of invasion. It was a significant difference in attitude, and neither side particularly liked the other. Greek Orthodox Christians considered the Franks barbarous and grasping; western Roman Catholics contemptuously called the eastern Christians “Greeks” and condemned them for their “Byzantine” cunning.

Thus, as with Islam’s Sunni-Shiite division, the Christian world was divided by differences in heritage, theology, customs, and levels of urbanization. At that time, the eastern Orthodox world was considerably more ancient and more cultured than the world of the Catholic west. Still, each had to deal with the threat posed by an expansive Islam. In Constantinople, eastern Christian armies fought to hold off Muslim forces that constantly threatened the integrity of the great city and its Christian hinterlands. In Europe, Muslim armies had been turned back from southern France, but Islam had succeeded in becoming firmly established in the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal). Western Christendom, led by the Roman papacy, set about spreading Christianity to pagan tribes in the north, and it began to contemplate how to retake lands from the Muslims. In spite of their deep political, ethnic, and theological differences, the two regions of Christianity still conducted a brisk trade in commodities and ideas.

Glossary

- monasticism

- From the Greek word monos (meaning “alone”), the practice of living without the ties of marriage or family, forsaking earthly luxuries for a life of prayer and study. While Christian monasticism originated in Egypt, a variant of ascetic life had long been practiced in Buddhism.

- Vikings

- Warrior group from Scandinavia that used its fighting skills and sophisticated ships to raid and trade deep into eastern Europe, southward into the Mediterranean, and westward to Iceland, Greenland, and North America.

- Greek Orthodoxy

- Branch of eastern Christianity, originally centered in Constantinople, that emphasizes the role of Jesus in helping humans achieve union with God.

- Roman Catholicism

- Western European Christianity, centered on the papacy in Rome, that emphasizes the atoning power of Jesus’s death and aims to expand as far as possible.