PUTTING IT INTO CONTEXT

What are the characteristics of universalizing religions? What was the relationship between empire and universalizing religion in the Roman Empire, Sasanian Persia, China, and elsewhere along the Silk Roads?

PUTTING IT INTO CONTEXT

What are the characteristics of universalizing religions? What was the relationship between empire and universalizing religion in the Roman Empire, Sasanian Persia, China, and elsewhere along the Silk Roads?

By the fourth century CE in western Afro-Eurasia, the Roman Empire was hardly the political and military juggernaut it had been 300 years earlier. Surrounded by peoples who coveted its wealth while resisting its power, Rome was fragmenting. So-called barbarians eventually overran the western part of the empire, but in many ways those areas still felt “Roman.” Rome’s endurance was a boon to the new religious activity that thrived in the turmoil of the immigrations and contracting political authority of the empire. Romans and so-called barbarians alike looked to the new faith of Christianity to maintain continuity with the past, eventually founding a central church in Rome to rule the remnants of empire.

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE Explain the ways in which Christianity developed and spread.

The spread of new religious ideas, including Christianity, in the Roman Empire changed the way people viewed their existence. Believing implied that an important otherworld loomed beyond the world of physical matter. Feeling contact with that other world gave worshippers a sense of worth; it guided them in this life, and they anticipated someday meeting their guides and spiritual friends there. No longer were the gods understood by believers as local powers to be placated by archaic rituals in sacred places. Many gods became omnipresent figures whom mortals could touch through loving attachment. As ordinary mortals now could hope to meet these divine beings in another, happier world, the sense of an afterlife glowed more brightly.

Christians’ emphasis on obedience to their Lord God, rather than to a human ruler, sparked a Mediterranean-wide debate on the nature of religion as well as texts that explored these issues. Christians, like the Jews from whose tradition their sect had sprung, read and followed divinely inspired scriptures that told them what to believe and do, even when those actions went against the empire’s laws. Christians spoke of their scriptures as “a divine codex.” Bound in a compact volume or set of volumes, this was the definitive code of God’s law that outlined proper belief and behavior. By the late fourth century CE, Christians had largely settled on a combination of Jewish scriptures and newly authoritative Christian texts—including history, laws, prophecy, biography, poetry, letters, and ideas about the end of days—that would come to be known as the Bible.

Another central feature of early Christianity was the figure of the martyr. Martyrs were women and men whom the Roman authorities executed for persisting in their Christian beliefs instead of submitting to emperor worship, as we saw in this chapter’s opening story of the twelve Scillitan martyrs—so-called for the town in North Africa from which they came. While other religions, including Judaism and later Islam, honored martyrs who died for their faith, Christianity claimed to be based directly on “the blood of martyrs,” in the words of the North African Christian theologian Tertullian (writing around 200 CE).

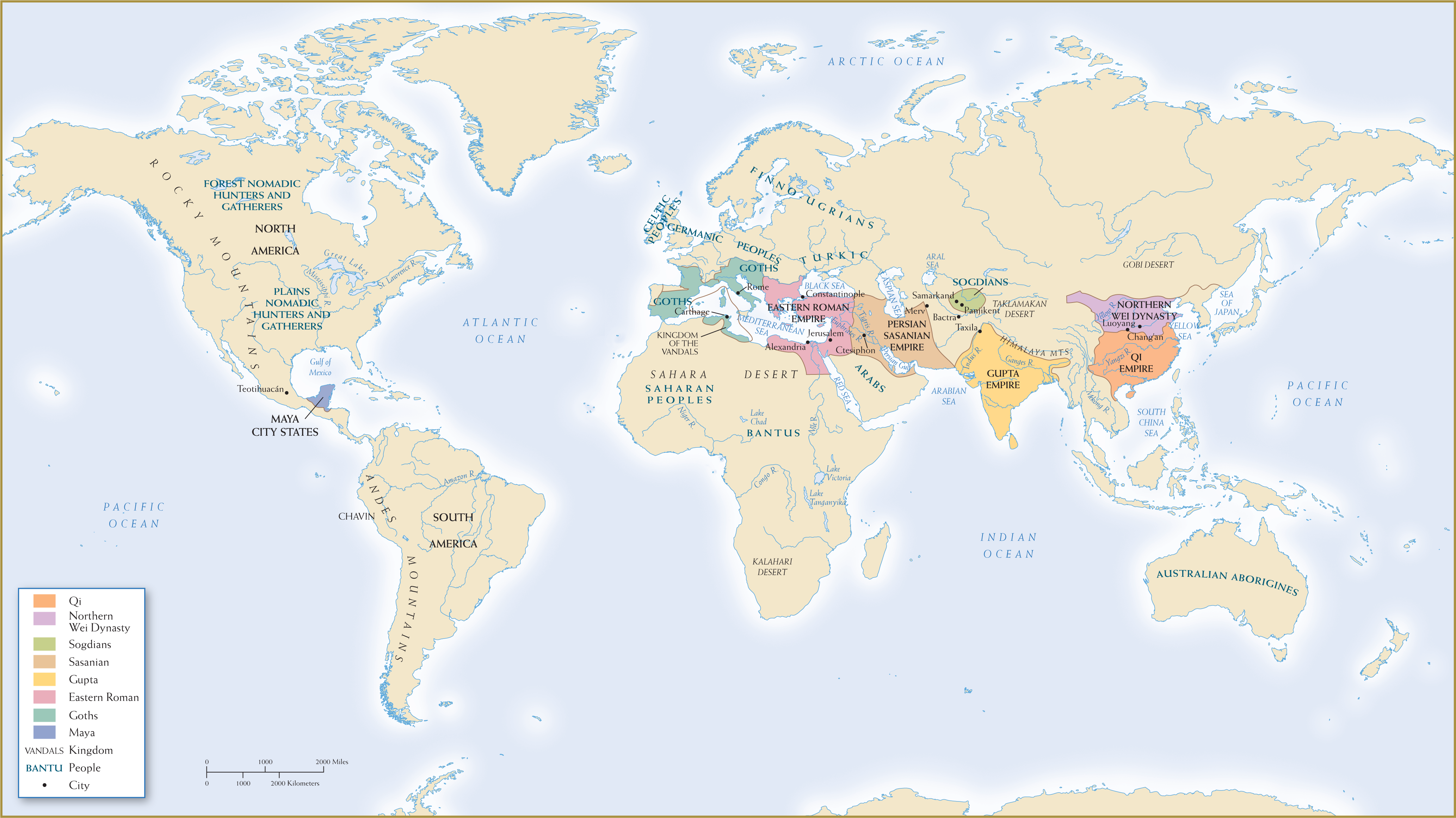

The Global View

Map 1.1 Empires and Universalizing Religions, 300–600 CE

The period from 300 to 600 CE was a time of tumultuous political change accompanied by the spread of adaptable and accessible universalizing faiths.

Map 1.2 The Spread of Universalizing Religions in Afro-Eurasia, 300–600 CE

The spread of universalizing religions and the shifting political landscape were intimately connected.

The story of Vibia Perpetua, a well-to-do mother in her early twenties, offers a striking example of martyrdom. Refusing to sacrifice to the Roman gods, Perpetua and her maidservant Felicitas, along with their companions, were condemned in 203 CE to face wild beasts in the amphitheater of Carthage, a venue small enough that the condemned and the spectators would have had eye contact with one another throughout the fatal encounter. The prison diary that Perpetua dictated before her death offered to Christians and potential converts a powerful religious message that balanced heavenly visions and rewards with her concerns over responsibility to her father, brother, and infant son. The remembered heroism of women martyrs like Perpetua and Felicitas offset the increasingly male leadership—bishops and clergy—of the institutionalized Christian church.

Constantine: From Conversion to Creed Crucial in spurring Christianity’s spread was the transformative experience of Constantine (c. 280–337 CE).Born near the Danubian frontier, he belonged to a class of professional soldiers whose careers took them far from the Mediterranean. Constantine’s troops proclaimed him emperor after the death of his father, the emperor Constantius. In the civil war that followed, Constantine looked for signs from the gods. Before the decisive battle for Rome, which took place at a strategic bridge in 312 CE, he supposedly had a dream in which he saw an emblem bearing the words “In this sign conquer.” The “sign,” which he then placed on his soldiers’ shields, was the first two letters of the Greek christos, a title for Jesus meaning “anointed one.” Constantine’s troops won the ensuing battle and, thereafter, Constantine’s visionary sign became known all over the Roman world. Constantine showered imperial favor on this once-persecuted faith, not only legalizing Christianity (in 313 CE) but also praising the work of Christian bishops and granting them significant tax exemptions.

By the time Constantine embraced Christianity, it had already made considerable progress within the Roman Empire. It had prevailed in the face of stiff competition and periodically intense persecution from the imperial authorities. Apart from the new imperial endorsement, Christianity’s success could be attributed to the sacred aura surrounding its authoritative texts, the charisma of its holy men and women, the fit that existed between its doctrines and popular preexisting religious beliefs and practices, and its broad, universalizing appeal to rich and poor, city dwellers and peasants, slaves and free people, young and old, and men and women.

CONTEXTUALIZATION Evaluate the extent to which Constantine’s embrace of Christianity supported that religion’s growth within the Roman Empire.

In 325 CE, hoping to bring unity to the diversity of belief within Christian communities, Constantine summoned all bishops to Nicaea (modern Iznik in western Turkey) for a council to develop a statement of belief, or creed (from the Latin credo, “I believe”). The resulting Nicene Creed balanced three separate divine entities—God “the father,” “the son,” and “the holy spirit”—as facets of one supreme being. Also at Nicaea the bishops agreed to hold Easter, the day on which Christians celebrate Christ’s resurrection, on the same day in every church of the Christian world. Writing near the end of Constantine’s reign, an elderly bishop in Palestine named Eusebius noted that the Roman Empire of his day would have surprised the martyrs of Carthage, who had willingly died rather than recognize any “empire of this world.”

COMPARISON Compare the administrative functions of the Roman Empire with those of Christian churches.

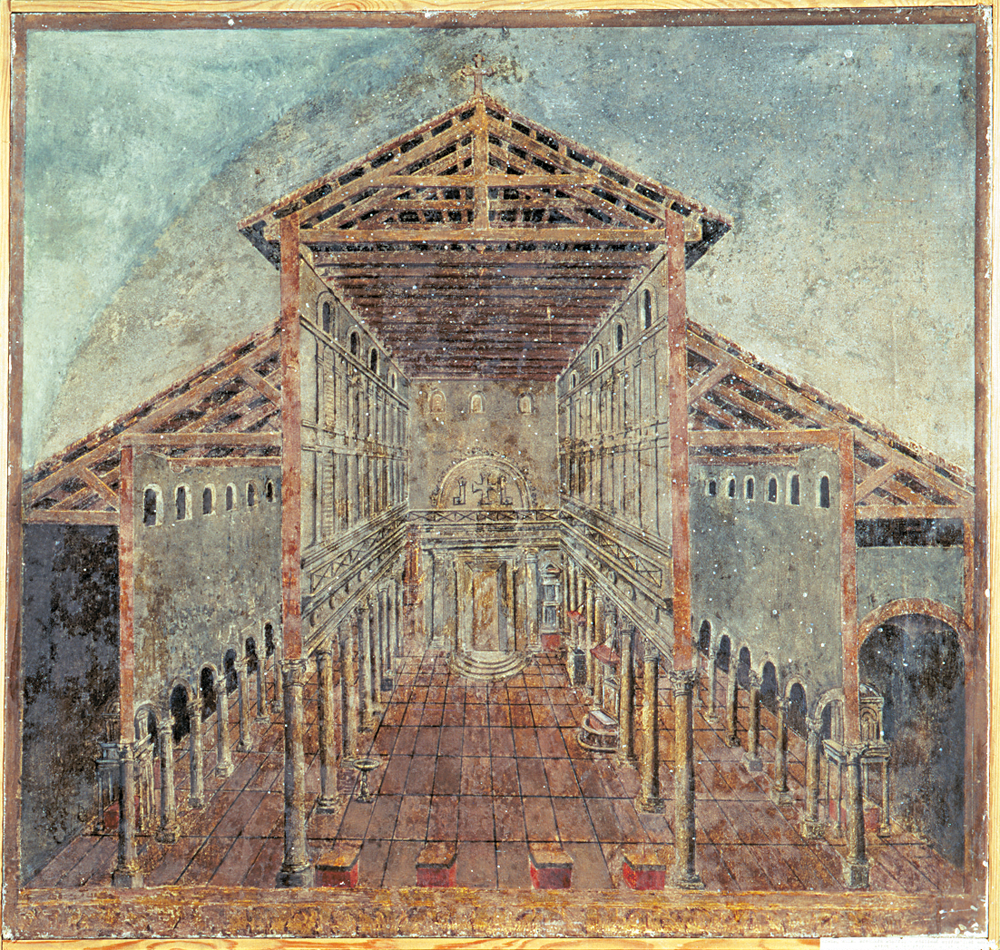

Christianity in the Cities and Beyond After 312 CE, the large churches built in every major city, many with imperial funding, signaled Christianity’s growing strength. These gigantic meeting halls were called basilicas, from the Greek word basileus, meaning “king.” They were modeled on Roman law-court buildings and could accommodate over a thousand worshippers. Inside a basilica’s vast space, oil lamps shimmered on marble and brought mosaics to life. Rich silk hangings, swaying between rows of columns, increased the sense of mystery and directed the eye to the far end of the building—a splendidly furnished semicircular apse. Under the dome of the apse, which represented the dome of heaven, and surrounded by priests, the bishop sat and preached from his special throne, or cathedra.

These basilicas became the new urban public forums, ringed with spacious courtyards where the city’s poor would gather. In return for the tax exemptions that Constantine had granted them, bishops cared for the metropolitan poor. Bishops also became judges, as Constantine turned their arbitration process for disputes between Christians into a kind of small claims court. Offering the poor shelter, quick justice, and moments of unearthly splendor in grand basilicas, Christian bishops perpetuated “Rome” for centuries after the empire had disappeared.

The spread of Christianity outside the cities and into the hinterlandsof Africa and Southwest Asia required the breaking of language barriers. In Egypt, Christian clergy replaced hieroglyphics with Coptic, a more accessible script based on Greek letters, in an effort to bridge the linguistic and cultural gap between town and countryside. In the crucial corridor that joined Antioch to Mesopotamia, Syriac, an offshoot of the Semitic language Aramaic, became a major Christian language. As Christianity spread farther north, to Georgia in the Caucasus and to Armenia, Christian clergy created written languages that are still used in those regions.

Continuity and the “Fall”

Continuity and the “Fall”

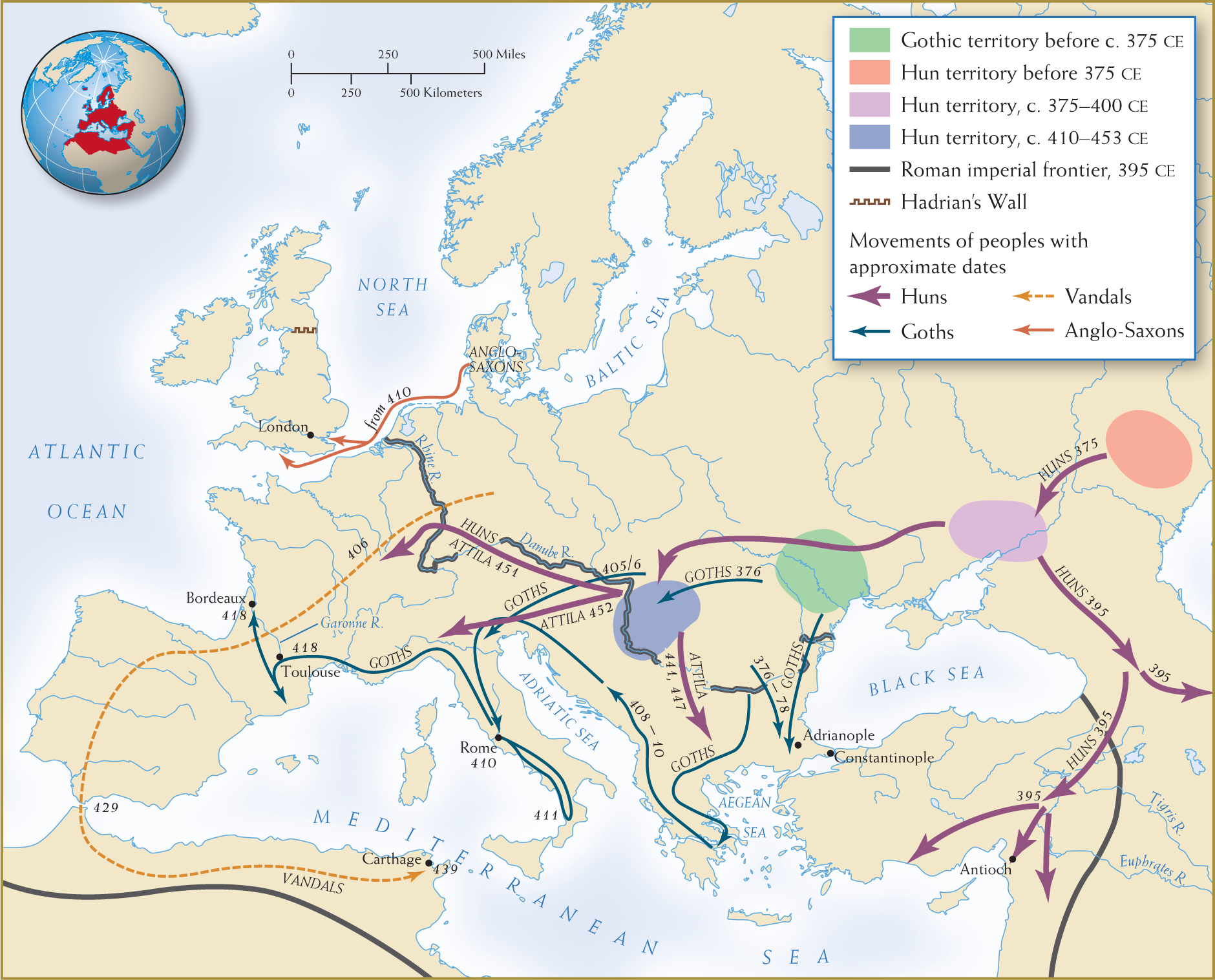

By the third and fourth centuries CE, the political and economic fabric of the old Roman world was unraveling. (See Map 1.3.) The so-called barbarian invasions of the late fourth and fifth centuries CE further contributed to that demise. These “invasions” were not so much an assault as a violent and chaotic immigration of young fighting men from the frontiers of the empire. Today the term barbarian implies uncultivated or savage, but its meaning in antiquity was “foreigner” (with overtones of inferiority). Inhabitants of the empire’s western provinces had become accustomed to non-Roman soldiers from across the frontiers, and for them barbarian was synonymous with “soldier.” The popular image of bloodthirsty barbarian hordes streaming into the empire bears little resemblance to reality. (See Current Trends in World History: Fall of the Roman and Han Empires: A Comparative Perspective.)

The Goths It was the Romans’ need for soldiers that drew the barbarians in. The process reached a crisis point when tribes of Goths petitioned the emperor Valens (r. 365–378 CE) to let them immigrate into the empire. These Goths were no strangers to Roman influence: in fact, many had been evangelized into an anti-Nicene version of Christianity by the Gothic bishop Ulfilas, who had even translated the Bible into the Gothic language using an alphabet he developed for that purpose.

Valens, desperate for manpower, encouraged the Goths’ entrance into Roman territory but mistreated these new immigrants. A lethal combination of famine and anger at the breakdown of supplies—not innate bloodlust—turned the Goths against Valens. When he marched against them at Adrianople in the hot August of 378 CE, Valens was not seeking to halt a barbarian invasion but rather intending to teach a lesson in obedience to his new recruits. The Gothic cavalry, however, proved too much for Valens’s imperial army, and the Romans were trampled to death by the men and horses they had hoped to hire. As the pattern of disgruntled “barbarian” immigrants, civil war, and overextension continued, the Roman Empire in western Europe crumbled.

Map 1.3 Western Afro-Eurasia: War, Immigration, and Settlement in the Roman World, 375–450 CE

Invasions and migrations brought about the reconstitution of the Roman Empire at this time.

CONTEXTUALIZATION Explain the reasons the Roman Empire was under attack during this period.

Rome’s maintenance of its northern borders required constant efforts and high taxes. But after 400 CE the western emperors could no longer raise enough taxes to maintain control of the provinces. In 418 CE, the Goths settled in southwest Gaul as a kind of local militia to fill the absence left by the contracting Roman authority. Ruled by their own king, who kept his military in order, the Goths suppressed alarmingly frequent peasant revolts. Roman landowners of Gaul and elsewhere anxiously allied themselves with the new military leaders rather than face social revolution and the raids of even more dangerous armies. Although they practiced a different, “heretical” version of Christianity, the Goths came as Christian allies of the aristocracy, not as godless enemies of Rome.

The Huns Romans and non-Romans also drew together to face a common enemy: the Huns. Led by their king Attila (406–453 CE) for twenty years, the Huns threatened both Romans and Germanic peoples (like the Goths). While the Romans could hide behind their walls, the Hunnish cavalry regularly plundered the scattered villages and open fields in the plains north of the Danube.

Attila intended to be a “real” emperor of a warrior aristocracy. Having seized (perhaps from the Chinese empire) the notion of a “mandate of heaven”—in his case, a divine right to rule the tribes of the north—he fashioned the first opposing empire that Rome ever had to face in northern Europe. Rather than selling his people’s services to Rome, Attila extracted thousands of pounds of gold coins in tribute from the Roman emperors who hoped to stave off assaults by his brutal forces. Drained both militarily and economically by this Hunnish threat, the Roman Empire in the west disintegrated only twenty years after Attila’s death. In 476 CE, the last Roman emperor of the west, a young boy named Romulus Augustulus (namesake of both Rome’s legendary founder and its first emperor), resigned to make way for a so-called barbarian king in Italy.

The political unity of the Roman Empire in the west now gave way to a sense of unity through the church. The Catholic Church (Catholic meaning “universal,” centered in the bishops’ authority) became the one institution to which all Christians in western Europe, Romans and non-Romans alike, felt that they belonged. The bishop of Rome became the symbolic head of the western churches. Rome became a spiritual capital instead of an imperial one. By 700 CE, the great Roman landowning families of the Republic and early empire had vanished, replaced by religious leaders with vast moral authority.

Elsewhere the Roman Empire was alive and well. From the borders of Greece to the borders of modern Iraq, and from the Danube River to Egypt and the borders of Saudi Arabia, the empire survived undamaged. The new Roman Empire of the east—to which historians gave the name Byzantium—had its own “New Rome,” Constantinople. Founded in 324 CE by its namesake, Constantine, on the Bosporus straits separating Europe from Asia, this strategically located city was well situated to receive taxes in gold and to control the sea-lanes of the eastern Mediterranean.

COMPARISON Compare the evolution of the Eastern and Western Roman Empires.

Constantinople was one of the most spectacularly successful cities in Afro-Eurasia, soon boasting a population of over half a million and 4,000 new palaces. Every year, more than 20,000 tons of grain arrived from Egypt, unloaded on a dockside over a mile long. A gigantic hippodrome echoing Rome’s Circus Maximus straddled the city’s central ridge, flanking an imperial palace whose opulent enclosed spaces stretched down to the busy shore. As they had for centuries before in Rome, emperors would sit in the imperial box, witnessing chariot races as rival teams careened around the stadium. The hippodrome also featured displays of eastern imperial might, as ambassadors came from as far away as central Asia, northern India, and Nubia.

Similarly, the future emperor Justinian came to Constantinople as a young man from an obscure Balkan village, to seek his fortune. When he became emperor in 527 CE, he considered himself the successor of a long line of forceful Roman emperors—and he was determined to outdo them. Most important, Justinian reformed Roman laws. Within six years a commission of lawyers had created the Digest, a massive condensation and organization of the preexisting body of Roman law. Its companion volume was the Institutes, a teacher’s manual for schools of Roman law. These works were the foundation of what later ages came to know as “Roman law,” followed in both eastern and western Europe for more than a millennium.

Reflecting the marriage of Christianity with empire was Hagia Sophia, a church grandly rebuilt by Justinian on the site of two earlier basilicas. The basilica of Saint Peter in Rome, the largest church built by Constantine two centuries earlier, would have reached only as high as the lower galleries of Hagia Sophia. Walls of multicolored marble, gigantic columns of green and purple granite, audaciously curved semicircular niches placed at every corner, and a spectacular dome lined with gleaming gold mosaics inspired awe in those who entered its doors. Hagia Sophia represented the flowing together of Christianity and imperial culture that for another 1,000 years would mark the Eastern Roman Empire centered in Constantinople.

Internal discord, as well as contacts between east and west, intensified during Justinian’s reign. Justinian quelled riots at the heart of Byzantium, like the weeklong Nika riots in 532 CE in which thousands died when a group of senators used the unrest and high emotions of the chariot races as a cover for revolt. He also undertook wars to reclaim parts of the western Mediterranean and to hold off the threat from Sasanian Persia in the east (see next section). Perhaps the most grisly reminder of this increased connectivity was a sudden onslaught in 541–542 CE of the bubonic plague from the east. One-third of the population of Constantinople died within weeks. Justinian himself survived, but thereafter he ruled an empire whose heartland was decimated. Nonetheless, Justinian’s contributions—to the law, to Christianity, to the maintenance of imperial order—helped Byzantium last almost a millennium after Rome in the west had fallen away.