Religious Ideas in Worlds Apart

Religious Ideas in Worlds Apart

Faith and Cultures in the Worlds Apart

Core Objectives

ASSESS the connections between political unity and religious developments in sub-Saharan Africa and Mesoamerica in the fourth to sixth centuries CE.

In most areas of sub-Saharan Africa and Mesoamerica, it was not easy for ideas, institutions, peoples, and commodities to circulate broadly. Thus, we do not see the development of universalizing faiths like those in Eurasia. Rather, belief systems and their associated deities remained local. Nonetheless, sub-Saharan Africans and peoples living in Mesoamerica revered prophetic figures who, they believed, communicated with deities and brought to humankind divinely prescribed rules of behavior. Peoples in both regions honored beliefs and rules that were passed down orally across generations. These unifying spiritual traditions guided behavior and established social customs.

BANTUS OF SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

AP® Skills & Processes

CAUSATION Evaluate the extent to which Bantu migrations affected sub-Saharan Africa.

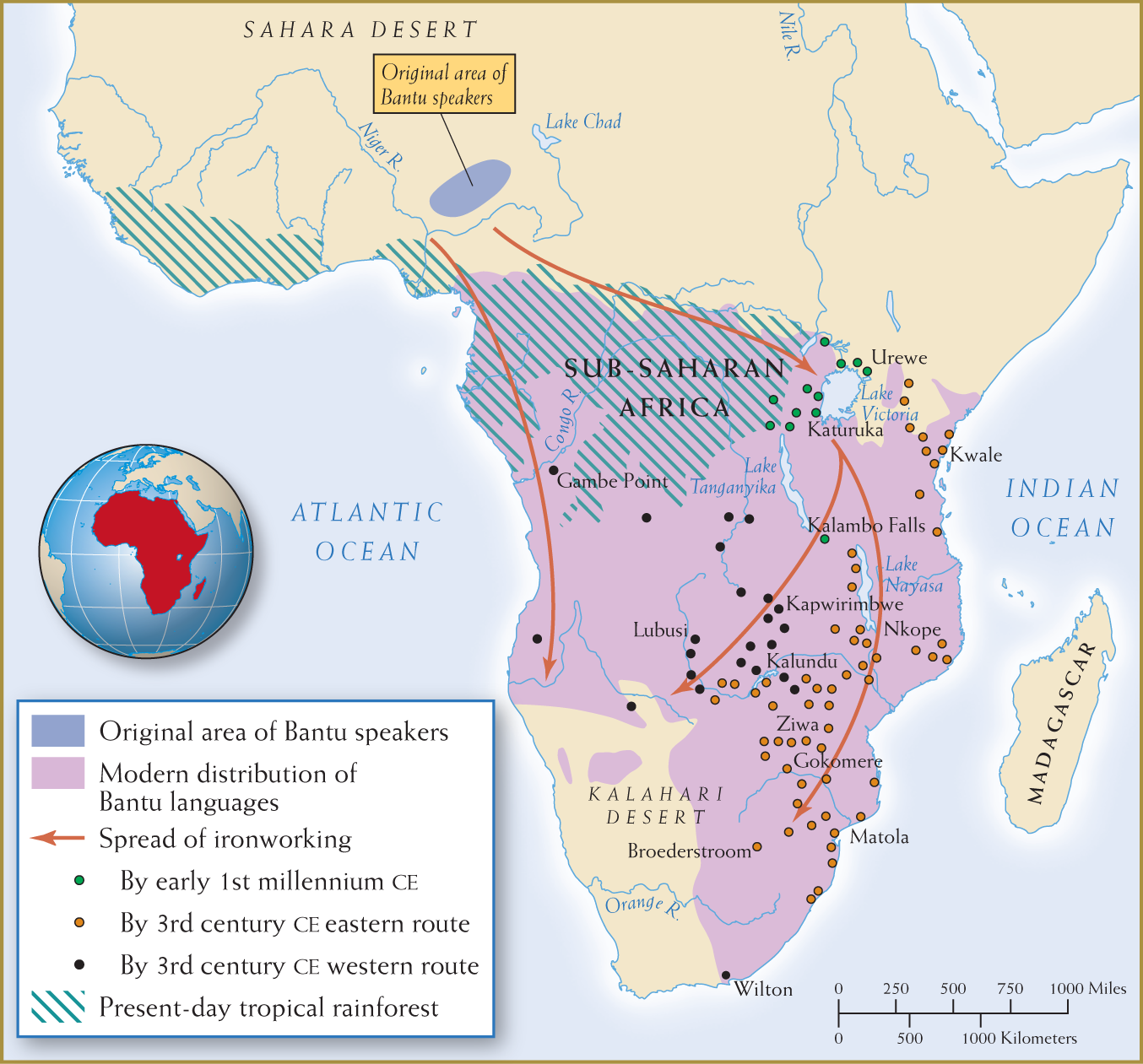

Today, most of Africa south of the equator is home to peoples who speak some variant of more than 400 Bantu languages. Although scholars using oral traditions and linguistic evidence can trace a clear narrative of the Bantu people no farther back than 1000 CE, it appears that the first Bantu speakers lived in the southeastern part of modern Nigeria, where about 4,000 or 5,000 years ago they likely shifted from hunting, gathering, and fishing to practicing settled agriculture. Preparing just one acre of tropical rain forest for farming required removing 600 tons of moist vegetation. To accomplish this arduous task, Bantus used mainly machetes, billhooks, and controlled burning. Bantus cultivated woodland plants such as yams and mushrooms, as well as palm oils and kernels. Yet the difficulties in preparing the land for settled agriculture did not keep the Bantus from being the most expansionist of African peoples. (See Map 1.6.)

Bantu Migrations Following riverbeds and elephant trails, Bantu migrants traveled out of West Africa in two great waves. One wave moved across the Congo forest region to East Africa. Their knowledge of iron smelting enabled them to deploy iron tools for agriculture. Because their new habitats supported a mixed economy of animal husbandry and sedentary agriculture, this group became relatively prosperous. A second wave of migrants moved southward through the rain forests in present-day Congo, eventually reaching the Kalahari Desert. The tsetse fly–infested environment did not permit them to rear livestock, so they were limited to subsistence farming. These Bantus learned to use iron later than those who had moved to the Congo region in the east.

Map 1.6 Bantu Migrations in Africa

The migration of Bantu speakers throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa in the first millennium CE dramatically altered the cultural landscape.

- According to the map, where did the Bantu speakers originate? Into which areas did the Bantu speakers migrate? Why might they have migrated in that direction?

- Trace the spread of ironworking with the Bantu speakers. How might ironworking have enabled Bantu speakers to dominate the peoples already living there?

- What range of topography and ecological zones did the Bantu speakers encounter as they moved southward and eastward? How might that have influenced their spread into new regions?

Precisely when these Bantu migrations began is unclear, but once under way, the travelers moved rapidly. Genetic and linguistic evidence reveals that they absorbed most of the hunting and gathering populations who originally inhabited these areas. What enabled the Bantus to prevail and prosper was their skill as settled agriculturalists. They adapted their farming techniques and crops to widely different environments, including the tropical rain forests of the Congo River basin, the savanna lands of central Africa, the high grasslands around Lake Nyanza, and the highlands of Kenya.

For the Bantu of the rain forests of Central Africa (the western Bantu), the introduction of the banana plant from tropical South and Southeast Asia was decisive. Linguistic evidence suggests that it first arrived in the Upper Nile region and then traveled into the rest of Africa with small groups migrating from one favorable location to another; the earliest proof of its presence is a record from the East African coast dating to 525 CE. The banana adapted well to the equatorial rain forests, withstanding the heavy rainfalls, requiring less clearing of rain forests, reducing the presence of the malaria-carrying Anopheles mosquito, and providing more nutrients than the indigenous yam crop. Exploiting banana cultivation, the western Bantu filled the equatorial rain forests of central Africa between 500 and 1000 CE.

Bantu Cultures, East and West The widely different ecological zones into which the Bantu-speaking peoples spread made it difficult to establish the same political, social, and cultural institutions. In the Great Lakes area of the East African savanna lands and the savanna lands of Central Africa, where communication was relatively easy, the eastern Bantu speakers developed centralized polities whose kings ruled by divine right. They moved into heavily forested areas similar to those they had left in southeastern Nigeria. These locations supported a way of life that remained fundamentally unaltered until European colonialism in the twentieth century.

AP® Skills & Processes

COMPARISON Compare the Eastern and Western Bantu migrations.

The western Bantu-speaking communities of the lower Congo River rain forests formed small-scale societies based on family and clan connections. They organized themselves socially and politically into age groups, the most important of which were the ruling elders. Within these age-based networks, individuals who demonstrated talent in warfare, commerce, and politics provided leadership. Certain rights and duties were imposed on different social groups based mainly on their age. Males moved from child to warrior to ruling elder, and females transitioned from child to married child-bearer. Bonds among age groups were powerful, and movement from one to the next was marked by meaningful and well-remembered rituals. So-called big men, supported by followers attracted by their valor and wisdom as opposed to inheritance, promoted territorial expansion. Individuals who could attract a large community of followers, marry many women, and sire many children could lead their bands into new locations and establish dominant communities.

These rain forest communities held a common belief that the natural world was inhabited by spirits, many of whom were their own heroic ancestors. These spiritual beings intervened in mortals’ lives and required constant appeasement. Diviners helped men and women understand the spirits’ ways, and charms warded off the misfortune that aggrieved spirits might wish to inflict. Diviners and charms also protected against the injuries that living beings—witches and sorcerers—could inflict. In fact, much of the misfortune that occurred in the Bantu world was attributed to these malevolent forces. The Bantu migrations ultimately filled up more than half the African landmass. The Bantus spread a political and social order based on family and clan structures that rewarded individual achievement—and maintained an intense relationship to the world of nature that they believed was imbued with supernatural forces.

MESOAMERICANS

Core Objectives

COMPARE the unifying political and cultural developments in sub-Saharan Africa and Mesoamerica with those that took place across Eurasia in this period.

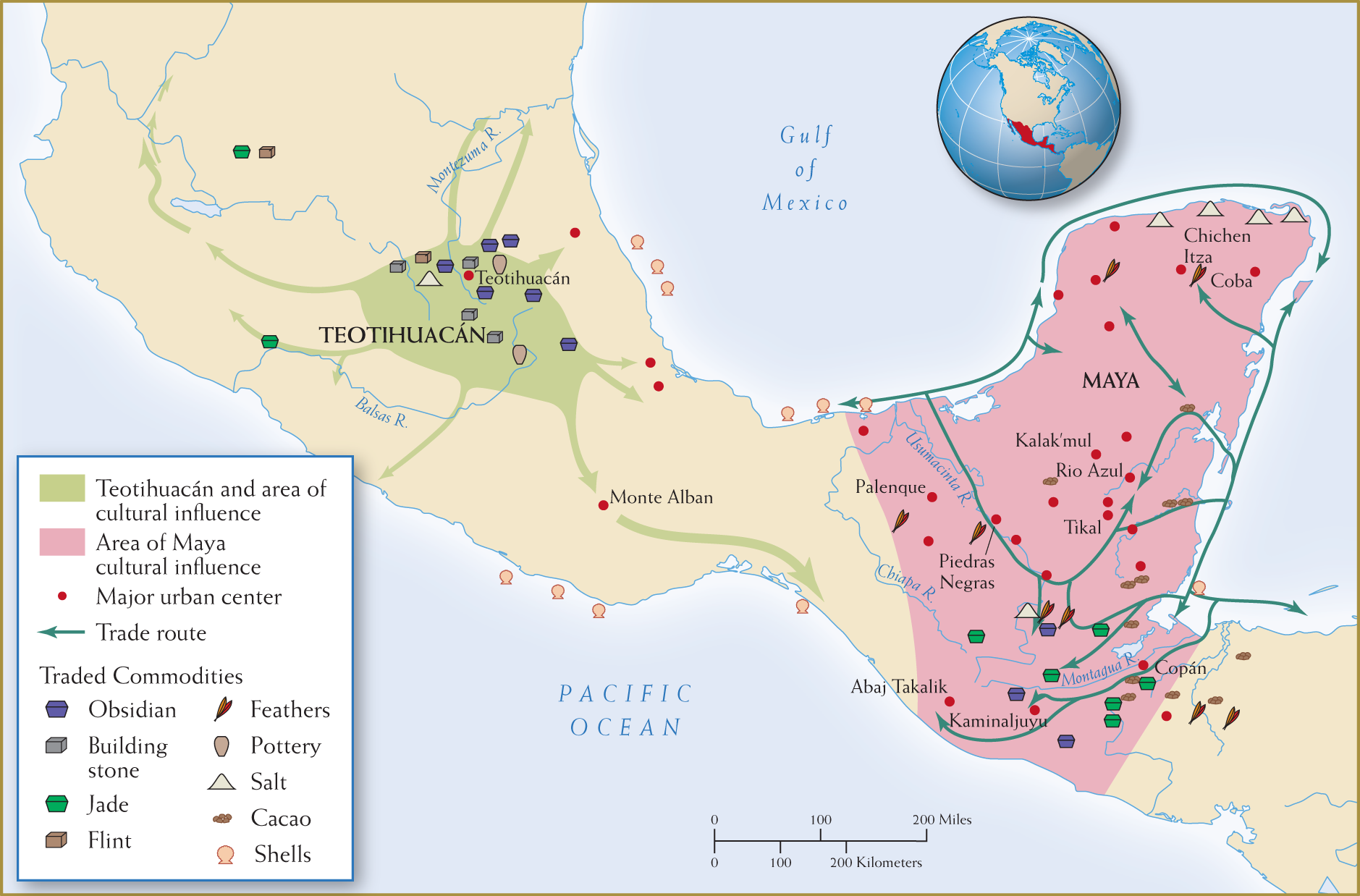

As in sub-Saharan Africa, the process of settlement and expansion in Mesoamerica differed from that in the large empires of Afro-Eurasia. Mesoamerica had no integrating artery of a giant river and its floodplain, and so it lacked the extensive resources that a state could harness for monumental ambitions. Nonetheless, some remarkable polities developed in the region, ranging from the city-state of Teotihuacán to the more widespread influence of the Maya. (See Map 1.7.)

Teotihuacán Around 300 BCE, people in the central plateau and the southeastern districts of Mesoamerica where the dispersed villages of Olmec culture had risen and fallen began to gather in larger settlements. Soon, political and social integration led to city-states. Teotihuacán, in the heart of the fertile valley of central Mexico, became the largest center of the Americas before the Aztecs almost 1,500 years later.

Map 1.7 Mesoamerican Worlds, 200–700 CE

At this time, two groups dominated Mesoamerica: one was located at the city of Teotihuacán in the center, and the other—the Maya—was in the south.

- Locate the traded commodities on the map. What do you note about the distribution of these commodities?

- Where are the trade routes located? What might have fostered interaction between Teotihuacán and the Maya?

Fertile land and ample water from the valley’s marshes and lakes fostered high agricultural productivity despite the inhabitants’ technologically rustic methods of cultivation. The local food supply sustained a metropolis of between 100,000 and 200,000 residents, living in more than 2,000 apartment compounds lining the city’s streets. At one corner rose the massive pyramids of the sun and the moon—the focus of spiritual life for the city dwellers. Marking the city’s center was the huge royal compound; the grandeur and refinement of its stepped stone pyramid, the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, were famous throughout Mesoamerica.

The feathered serpent was the anchor for the people’s spiritual lives. It was a symbol of fertility that governed reproduction and life. The feathered serpent’s temple was the core of a much larger structure. From it radiated the awesome promenade known as the Street of the Dead, which culminated in the hulking Pyramid of the Moon, where foreign warriors and dignitaries were mutilated, sacrificed, and often buried alive to consecrate the holy structure.

Teotihuacán was a powerful city-state that flexed its military muscle to overtake its rivals. By 300 CE, Teotihuacán controlled the entire basin of the Valley of Mexico. It dominated its neighbors and demanded gifts, tribute, and humans for ritual sacrifice. Its massive public architecture displayed art that commemorated decisive battles, defeated neighbors, and captured fighters. While the city’s political influence beyond the basin was limited, its cultural and economic diffusion were significant. Making use of porters, Teotihuacán’s merchants traded their ceramics, ornaments of marine shells, and all sorts of decorative and valued objects (especially of green obsidian) far and wide. At the same time, Teotihuacán imported pottery, feathers, and other goods from distant lowlands.

This kind of expansion left much of the political and cultural independence of neighbors intact, with only the threat of force keeping them in check. In the fifth century CE, however, invaders burned Teotihuacán and smashed the carved figurines of the central temples and palaces, targeting Teotihuacán’s institutional and spiritual core.

The Maya In the Caribbean region of the Yucatán and its interior, the Maya people flourished from about 250 CE to their zenith in the eighth century. The Maya lived in an inhospitable region—hot, infertile, lacking navigable river systems, and vulnerable to hurricanes. Yet the Maya established hundreds, possibly thousands, of agrarian villages scattered across the diverse ecological zones of present-day southern Mexico to western El Salvador. Villages were linked by a shared Mayan language and through tribute payments, chiefly from lesser settlements to sacred towns. At their peak the Maya may have numbered as many as 10 million.

Maya Political and Social Structure The Maya established a variety of kingdoms around major ritual centers—such as Palenque, Copán, and Piedras Negras—and their hinterlands. Such hubs were politically independent but culturally and economically interconnected through commerce. Some larger settlements, such as Tikal and Kalak’mul, became sprawling centers with dependent provinces. In 2018, scientists using jungle-penetrating laser scanning determined that many of the Maya centers were much larger and more densely settled than had been previously thought and that they had defensive walls, had extensive irrigation systems, and were connected by roads.

Maya culture encompassed about a dozen kingdoms that shared many features. Ambitious rulers in these larger states frequently engaged in hostilities with one another. Highly stratified, with an elaborate class structure, each kingdom was topped by a shamanistic king who legitimated his position via his lineage, reaching back to a founding father and, ultimately, the gods. The vast pantheon of gods included patrons of each subregion, as well as a creator god and deities for rain, maize, war, and the sun. Gods were neither especially cruel nor benevolent; rather, they focused on the dance that sustained the axis connecting the underworld and the skies. What humans had to worry about was making sure that the gods got the attention and reverence they needed.

This was the job of Maya rulers. Kings sponsored elaborate public rituals to reinforce their divine heritages, including ornate processions down their cities’ main boulevards to honor gods and their descendants, the rulers. Lords and their wives performed ritual blood sacrifice to feed their ancestors. A powerful priestly elite, scribes, legal experts, military advisers, and skilled artisans were vital to the hierarchy.

Most of the Maya people remained tied to the land, which could sustain a high population only through dispersed settlements. Poor soil quality and limited water supply prevented large-scale agriculture. Through terraces, the draining of fields, and slash-and-burn agriculture, Maya managed a subsistence economy of diversified agrarian production. Villagers cultivated maize, beans, and squash, rotating them to prevent the depletion of soil nutrients. Farmers supplemented these staples with root crops such as sweet potato and cassava. Cotton—the basic fiber used for clothing—frequently grew amid rows of other crops as part of a diversified mix.

Maya Writing, Mathematics, and Architecture A common set of beliefs, codes, and values connected the dispersed Maya villages. Sharing a similar language, the Maya developed writing and an important class of scribes, who were vital to the society’s integration. Rulers rewarded scribes for writing grand epics about dynasties and their founders, major battles, marriages, deaths, and sacrifices. Such writings offered to Maya shared common histories, beliefs, and gods—always associated with the narratives of ruling families.

The best-known surviving text is the Popol Vuh, a “Book of Community.” It narrates one community’s creation myth, extolling its founders (twin heroes) and the experiences—wars, natural disasters, human ingenuity—that enabled a royal line to rule the Quiché kingdom. The text begins with the gods’ creation of the earth and ends with the rituals the kingdom’s tribes must follow to avoid a descent into social and political anarchy, which had occurred several times throughout their history.

The Maya also had skilled mathematicians, who devised a calendar and studied astronomy. They accurately charted regular celestial movements and marked the passage of time by precise lunar and solar cycles. The Maya kept sacred calendars, by which they rigorously observed their rituals at the proper times. Each change in the cycle had particular rituals, dances, performances, and offerings to honor the gods with life’s sustenance.

Cities reflected a ruler’s ability to summon his subjects to contribute to the kingdom’s greatness. Plazas, ball courts, terraces, and palaces sprawled out from neighborhoods. Activity revolved around grand royal palaces and massive ball courts, where competing teams treated enthusiastic audiences to contests that were more religious ritual than game. The Maya also excelled at building monumental structures. In Tikal, for instance, surviving buildings include six massive, steep funerary pyramids featuring elaborately carved and painted masonry walls, vaulted ceilings, and royal burial chambers; the tallest temple soars more than 220 feet high (40 feet higher than Justinian’s Hagia Sophia).

Maya Bloodletting and Warfare Maya elites were obsessed with spilling blood as a way to honor rulers and ancestors as well as gods. This gory rite led to frequent warfare, especially among rival dynasties, the goal of which was to capture victims for the bloody rituals. Rulers also would shed their own blood at intervals set by the calendar. Royal wives drew blood from their tongues and men had their penises perforated. Such bloodletting by means of elaborately adorned and sanctified instruments was reserved for those of noble descent. Carvings and paintings portray blood cascading from rulers’ mutilated bodies.

AP® Skills & Processes

CAUSATION Describe the factors that kept Teotihuacán and the Maya from expanding their areas of control.

Internal warfare eventually doomed the Maya, especially after devastating confrontations between Tikal and Kalak’mul during the fourth through seventh centuries CE. With each outbreak, rulers drafted larger armies and sacrificed greater numbers of captives. Crops perished. People fled. After centuries of misery, it must have seemed as if the gods themselves were abandoning the Maya people. The cycle of violence destroyed the cultural underpinnings of elite rule that had held the Maya world together. There was no single catastrophic event, no great defeat by a rival power. The Maya people simply abandoned their spiritual centers, and cities became ghost towns. As populations declined, jungles overtook temples. Eventually, the hallmark of Maya unity—the ability to read a shared script—vanished. While vibrant religious traditions thrived in sub-Saharan Africa and in Mesoamerica, they served more to reinforce the political and social situations from which they came rather than to spread a universalizing message far beyond their original context.

Glossary

- Bantu migrations

- Waves of population movement from West Africa into eastern and southern Africa during the first millennium CE, bringing new agricultural practices to these regions and absorbing much of the hunting and gathering population.