PUTTING IT INTO CONTEXT

What cultural, political, and economic factors influenced the expansion of Islam, Buddhism, and Christianity from 600 to 1000 CE?

PUTTING IT INTO CONTEXT

What cultural, political, and economic factors influenced the expansion of Islam, Buddhism, and Christianity from 600 to 1000 CE?

Islam began inside Arabia. Despite its remoteness and sparse population, by the sixth century CE Arabia was brushing up against exciting outside currents: long-distance trade, religious debate, and imperial politics. The Hijaz—the western region of Arabia bordering the Red Sea—knew the outside world through trading routes reaching up the coast to the Mediterranean. Mecca, located in the Hijaz, was an unimposing village of simple mud huts. Mecca’s inhabitants included both merchants and the caretakers of a revered sanctuary called the Kaaba, a dwelling place of deities. In this remote region, one of the world’s major prophets emerged, and the universalizing faith he founded soon spread from Arabia through the trade routes stretching across Southwest Asia and North Africa.

Born in Mecca around 570 CE into a well-respected tribal family, Muhammad enjoyed only moderate success as a trader. Then came a revelation that would convert him into a proselytizer of a new faith. In 610 CE, while Muhammad was on a monthlong spiritual retreat in the hills near Mecca, he believed that God came to him in a vision and commanded him to recite a series of revelations.

CONTEXTUALIZATION Explain the origins of the Quran. What were the elements of universalizing religion in Islam?

The early revelations were short and powerful, emphasizing a single, all-powerful God (Allah) and providing instructions for Muhammad’s fellow Meccans to carry this message to nonbelievers. Muhammad’s early preaching had a clear message. He urged his small band of followers to act righteously, to set aside false deities, to submit themselves to the one and only true God, and to care for the less fortunate—for the Day of Judgment was imminent. Muhammad’s most insistent message was the oneness of God, a belief that has remained central to the Islamic faith ever since.

These teachings, compiled into an authoritative version after the Prophet’s death, constituted the foundational text of Islam: the Quran. Accepted as the word of God, the Quran’s verses were understood to have flowed flawlessly through God’s perfect instrument, the Prophet Muhammad. Muhammad believed that he was a prophet in the tradition of Moses, other Hebrew prophets, and Jesus and that he communicated with the same God that they did. The Quran and Muhammad proclaimed the tenets of a new faith to unite a people and expand the faith’s spiritual frontiers. Islam’s message already had universalizing elements, though how far it was to be extended, whether to the tribesmen living in the Arabian Peninsula or well beyond, was not at all clear at first.

In 622 CE, Muhammad and a small group of followers, opposed by Mecca’sleaders because of their radical religious beliefs and their challenge to the ruling elite’s authority, escaped to Yathrib (later named Medina). The perilous 200-mile journey, known as the hijra (“breaking off of relations” or “departure”), yielded a new form of communal unity: the umma (“band of the faithful”). So significant was this moment that Muslims date the beginning of the Muslim era from this year.

Medina became the birthplace of a new faith called Islam (“submission”—in this case, to the will of God) and a new community called Muslims (“those who submit”). The city of Medina had been facing tribal and religious tensions, and by inviting Muhammad and his followers to take up residence there, its elders hoped that his leadership and charisma would bring peace and unity to their city. Early in his stay Muhammad put forth the Constitution of Medina, which required the community’s people to refer all disputes to God and him. Now the residents were expected to replace traditional family, clan, and tribal affiliations with loyalty to Muhammad as the last and the truest Prophet of God.

Over time, the core practices and beliefs of every Muslim would crystallize as the five pillars of Islam. Muslims were expected to (1) proclaim the phrase “there is no God but God and Muhammad is His Prophet”; (2) pray five times daily facing Mecca; (3) fast from sunup until sundown during the month of Ramadan; (4) travel on a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in a lifetime if their personal resources permitted; and (5) pay alms in the form of taxation that would alleviate the hardships of the poor. These clear-cut expectations gave the imperial system that soon developed a doctrinal and legal structure and a broad appeal to diverse populations.

In 632 CE, in his early sixties, the Prophet passed away; but Islam remained vibrant thanks to the energy of its early followers—especially Muhammad’s first four successors, the “rightly guided caliphs” (the Arabic word khalīfa means “successor”). These caliphs ruled over Muslim peoples and theexpanding state. They institutionalized the new faith. They set the new religion on the pathway to imperial greatness by linking religious uprightness with territorial expansion, empire building, and an appeal to all peoples. (See Current Trends in World History: The Origins of Islam in the Late Antique Period: A Historiographical Breakthrough.)

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE Explain the earliest spread of Islam.

Driven by religious fervor and a desire to acquire the wealth of conquered territories, Muslim soldiers embarked on military conquests and sought to found a far-reaching territorial empire. This expansion of the Islamic state was one aspect of the struggle that they called jihad, between the dar al-Islam (“the world of Islam”) and the dar al-harb (“the world of warfare”). Within fifteen years, their skill in desert warfare and their inspired military leadership enabled Muslim soldiers to expand the dar al-Islam into Syria, Egypt, and Iraq—centerpieces of the former Byzantine and Sasanian Empires. The Byzantines saved the core of their empire by pulling back to the highlands of Anatolia, where they could defend their frontiers. In contrast, the Sasanians hurled their remaining military resources against the Muslim armies, only to be annihilated.

A political vacuum opened in the new and growing Islamic empire with the assassination of Ali, the last of the “rightly guided caliphs.” Ali was arguably the first male convert to Islam and had proved a fierce leader in the early battles for expansion. The Umayyads, a branch of one of the Meccan clans, laid claim to Ali’s legacy. Having been governors of the province of Syria under Ali, the Umayyads relocated the capital to the Syrian city of Damascus and introduced a hereditary monarchy, the Umayyad caliphate, in 661 CE to resolve leadership disputes. Although tolerant of conquered populations, Umayyad dynasts did not permit non-Arabic-speaking converts to hold high political offices, an exclusive policy that contributed to their ultimate demise.

Little can be gleaned about Muhammad himself and the evolution of Islam from Arabic-Muslim sources known to have been written in the seventh century CE. Non-Muslim sources, especially Christian and Jewish texts, which are often unsympathetic to Muhammad and early Islam, are more abundant and contain useful data on the Prophet and the early messages of Islam. These non-Muslim sources raise questions about Muhammad’s birthplace, his relationship to the most powerful of the clans during his stay in Mecca, and even the date of his death. Many of these sources, as well as the Quran itself, stress the end-times content of Muhammad’s preachings and the actions of his followers. The conclusion that scholars derive from these sources is that it was only during the eighth century CE, in the middle of the Umayyad period, that Islam lost its end-of-the-world emphasis and settled into a long-term religious and political system.

The recent explosion of historical writing on the origins of Islam owes an enormous debt to the creation of the field of Late Antiquity, in particular the 1971 publication of Peter R. Brown’s pioneering work The World of Late Antiquity, AD 150 to 750. Although the study itself predated the surge in globally oriented studies, it was part of a powerful globalist impulse to create new chronologies and new geographies. Its impact compelled scholars of classical and Islamic history to expand their research boundaries as well as their linguistic abilities.

Late Antiquity, according to Brown, was characterized by cultural Hellenism, centered in the Mediterranean basin. While Christianity was a decidedly new religion, Christian theologians and philosophers like Origen, Athanasius, and Augustine employed Hellenic thought to assimilate Christianity to the Hellenism of the Greco-Roman world. Brown similarly recognized Islam’s incorporation of Mediterranean ideas. The Arabs, spilling out of the Arabian Peninsula, created an empire like that of the Roman-Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, even assimilating many Byzantine and Sasanian practices and preserving and adding to Greek learning, a heritage that they passed on to Europe at the time of the Renaissance. According to Brown, “[T]he religion of Islam . . . [was] the most rapid crisis in the religious history of the Late Antique period.” In another work, he added that “early Islam trembled on the brink of becoming (like its ancestors—Judaismand Christianity) a Mediterranean civilization.” For Brown, the true end of the Late Antique period came only in 750 CE with the foundation of the Abbasid dynasty. Islam’s new capital at Baghdad (rather than the more Mediterranean-oriented Umayyad capital in Damascus), along with its thrust eastward into Iran and farther east into Khurasan, turned Islam away from the Mediterranean basin and its Greco-Roman culture and institutions.

Brown’s challenge to Islamicists was to determine whether Islam in the first century of its existence was in fact an extension of Late Antiquity. In truth, historians of Islam were slow to accept the challenge, noting that other than the Quran itself, what we know about Islam’s first two centuries comes from Muslim sources written in the eighth, ninth, and even tenth centuries CE. But in reality, there was a substantial non-Muslim literature on the origins of Islam that in spite of biases against Islam contained vital information on its origins.

Nearly four decades after Brown issued his challenge, classicists and Islamicists started exploring the beginnings of Islam using non-Muslim sources, including Greek, Armenian, Aramaic, Latin, Hebrew, Samaritan, Pahlavi, Syriac, and Arabic texts. Now scholars have revised our understanding of Muhammad’s career, the emergence of a monotheistic creed in the Arabian Peninsula, and the Arabs’ aspiration to create a universal empire. One of these scholars, Aziz al-Azmeh, has asserted that the birth of Islam was not a rupture with earlier traditions but “an integral part of late antiquity.” An important finding from these new sources is that when Islam originated, Jews and Christians were welcomed and some became Muhammad’s early followers. Moreover, as the Arabs poured out of the Arabian Peninsula into Syria, Iraq, and Egypt, they did not see themselves as carrying a new religion. As monotheists, they welcomed alliances with Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians. Islam did not emerge as a separate confessional religion, with many of the features that exist today, until the reign of the Umayyad ruler Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685–705). Much of the evidence comes from non-Muslimsources, but evidence also appears on coins minted in the name of Abd al-Malik and, especially, on the Dome of the Rock, a building constructed in 692 in Jerusalem by Abd al-Malik. The coins and the building bear numerous inscriptions, many of them from the Quran, that proclaim the distinctiveness of Islam from Christianity and Judaism.

Sources: Peter R. Brown, The World of Late Antiquity, AD 150 to 750 (London: Thames & Hudson, 1971; reprint as Norton Paperback, 1989), p. 189; Peter R. Brown, Society and the Holy in Late Antiquity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), p. 68; Aziz al-Azmeh, The Emergence of Islam in Late Antiquity: Allah and His People (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 2–3.

Questions for Analysis

Explore Further

al-Azmeh, Aziz, The Emergence of Islam in Late Antiquity: Allah and His People (2014).

Bowersock, G. W., The Crucible of Islam (2017).

Donner, Fred M., Muhammad and the Believers at the Origins of Islam (2010).

Grabar, Oleg, The Shape of the Holy: Early Islamic Jerusalem (1996).

Hoyland, Robert G., In God’s Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire (2015).

Robinson, Chase F., ‘Abd al-Malik (2005).

Shoemaker, Stephen J., The Death of a Prophet: The End of Muhammad’s Life and the Beginnings of Islam (2012).

The only Muslim source that we have on Muhammad and early Islam is the Quran itself, which, according to Muslim tradition, was compiled during the caliphate of Uthman (r. 644–655 CE). Recent scholarship has questioned this claim, suggesting a later date, sometime in the early eighth century CE, for the standardization of the Quran. Some scholars even contend that the text by then had additions to, and redactions of, Muhammad’s message. The Quran, in fact, is quiet on some of the most important events of Muhammad’s life. It mentions the name of Muhammad only four times. For more information, scholars have depended on biographies of Muhammad, one of the first of which was compiled by Ibn Ishaq (704–767 CE ); this work is not available to present scholars, but it was used by later Muslim authorities, notably Ibn Hisham (d. 833 CE), who wrote The Life of Muhammad, and Islam’s most illustrious historian, Muhammad Ibn al-Jarir al-Tabari (838–925 CE). Although the works of these later writers come from the ninth and tenth centuries CE, Muslim tradition ever since has held these sources to be reliable on Muhammad’s life and the evolution of Islam after the death of the Prophet.

CONTEXTUALIZATION AND CONTINUITY AND CHANGE Explain how the Abbasids and Umayyads affected culture and politics in the Islamic world.

As the Umayyads spread Islam beyond Arabia, some peoples resisted what they experienced as Arab Umayyad religious impurity and repression. In particular, these peoples believed that the continuing discrimination against them despite their conversion to Islam was humiliating and unfair. The Arab Umayyad conquerors enslaved large numbers of non-Arabs. These slaves could leave their servile status only through manumission. Even so, these formerly enslaved or non-Arab peoples who converted found that they, too, were still regarded as lesser persons although they lived in Arab households and had become Muslims. This situation existed even though the Arabs totaled about 250,000 to 300,000 during the Umayyad era, while non-Arab populations were 100 times as populous, totaling between 25 and 30 million. The area where protest against Arab domination reached a crescendo was in the east, notably in Khurasan, where most of the Arab conquerors did not live separately from the local populations but instead lived in close contact with them and intermarried local, ethnically different women. Ultimately, a new coalition emerged under the Abbasi family, which claimed descent from the Prophet. Disgruntled provincial authorities and their military allies, as well as non-Arab converts, joined the movement.

After amassing a sizable military force, the Abbasid coalition trounced the Umayyad ruler in 750 CE and began its caliphate, which would last 500 years. The center of the Muslim state then shifted to Baghdad in Iraq (as we saw at the start of this chapter), signifying the eastward sprawl of the faith and its empire. This shift represented a success for non-Arab groups within Islam without eliminating Arab influence at the dynasty’s center—the capital, Baghdad, in Arabic-speaking Iraq.

Islam’s appeal to converts during the Abbasid period was diverse. Some turned to it for practical reasons, seeking reduced taxes or enhanced power. Others, particularly those living in ethnically and religiously diverse regions, welcomed the message of a single all-powerful God and a single community united by a clear code of laws. Islam, drawing its original impetus from the teachings and actions of a prophetic figure, followed the trajectory of Christianity and Buddhism and became a faith with a universalizing message and appeal. It owed much of its success to its ability to merge the contributions of vastly different geographic, economic, and intellectual territories into a rich yet unified culture. (See Map 2.1.)

The Caliphate An early challenge for the Abbasid rulers was to determine how traditional, or “Arab,” they could be and still rule so vast an empire. They chose to keep the bedrock political institution of the early Islamic state—the caliphate (the line of political rulers reaching back to Muhammad). Although the caliphs exercised political authority over the Muslim community, they were not understood to have inherited Muhammad’s prophetic powers or any authority in religious doctrine. That power was reserved for religious scholars, called ulama.

Abbasid rule borrowed practices from successful predecessors in its mixture of Persian absolute authority and the royal seclusion of the Byzantine emperors who lived in palaces far removed from their subjects. This blend of absolute authority and decentralized power involved a delicate and ultimately unsustainable balancing act. As the empire expanded, it became increasingly decentralized politically, enabling wily regional governors and competing caliphates in Spain and Egypt to grab power. Even as Islam’s political center diffused, though, its spiritual center remained fixed in Mecca, where many of the faithful gathered to fulfill their pilgrimage obligation.

The Army The Abbasids, like all rulers, relied on force to integrate their empire. Yet they struggled with what the nature of that military force should be: a citizen-conscript, all-Arab force or a professional, even non-Arab, army. In the early stages, leaders conscripted military forces from local Arab populations, creating citizen armies. Ultimately, however, the Abbasids recruited professional soldiers from Turkish-speaking communities in central Asia and from the non-Arab, Berber-speaking peoples of North and West Africa. Their reliance on foreign—that is, non-Arab—military personnel represented a major shift in the Islamic world. Not only did the change infuse the empire with dynamic new populations, but soon these groups gained political authority. Having begun as an Arab state that then incorporated strong Persian influence, the Islamic empire now embraced Turkish elements from the pastoral belts of central Asia.

CONTEXTUALIZATION How did Islamic law begin to develop during the Abbasid period?

Islamic Law (the Sharia) and Theology Islamic law, or the sharia, began to take shape in the Abbasid period. The work of generations of religious scholars, the sharia covers all aspects of practical and spiritual life, providing legal principles for marriage contracts, trade regulations, and religious prescriptions such as prayer, pilgrimage rites, and ritual fasting. The most influential early scholar of the sharia was an eighth-century Palestinian-born Arab, al-Shafi’i, who insisted that Muhammad’s laws as laid out in the Quran, in addition to his sayings and actions as written in later reports (hadith), provided all the legal guidance that Islamic judges needed. This shift gave ulama (Muslim scholars) a central place in Islam since only their spiritual authority, and not the political authority of the caliphs, was qualified to define religious law. The ulama’s ascendance opened a sharp division within Islam: between the secular realm of the caliphs and the religious sphere of religious judges, experts on Islamic law, teachers, and holy men.

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE Evaluate the extent to which women’s rights changed as Islam spread.

Gender in Early Islam Pre-Islamic Arabia was one of the last regions in Southwest Asia where patriarchy had not triumphed. Instead, men still married into women’s families and moved to those families’ locations, as was common in tribal communities. Some women engaged in a variety of occupations and, if they became wealthy, even married more than one husband. But contact with the rest of Southwest Asia, where men’s power over women prevailed, was already altering women’s status in the Arabian Peninsula before the birth of Muhammad.

The Global View

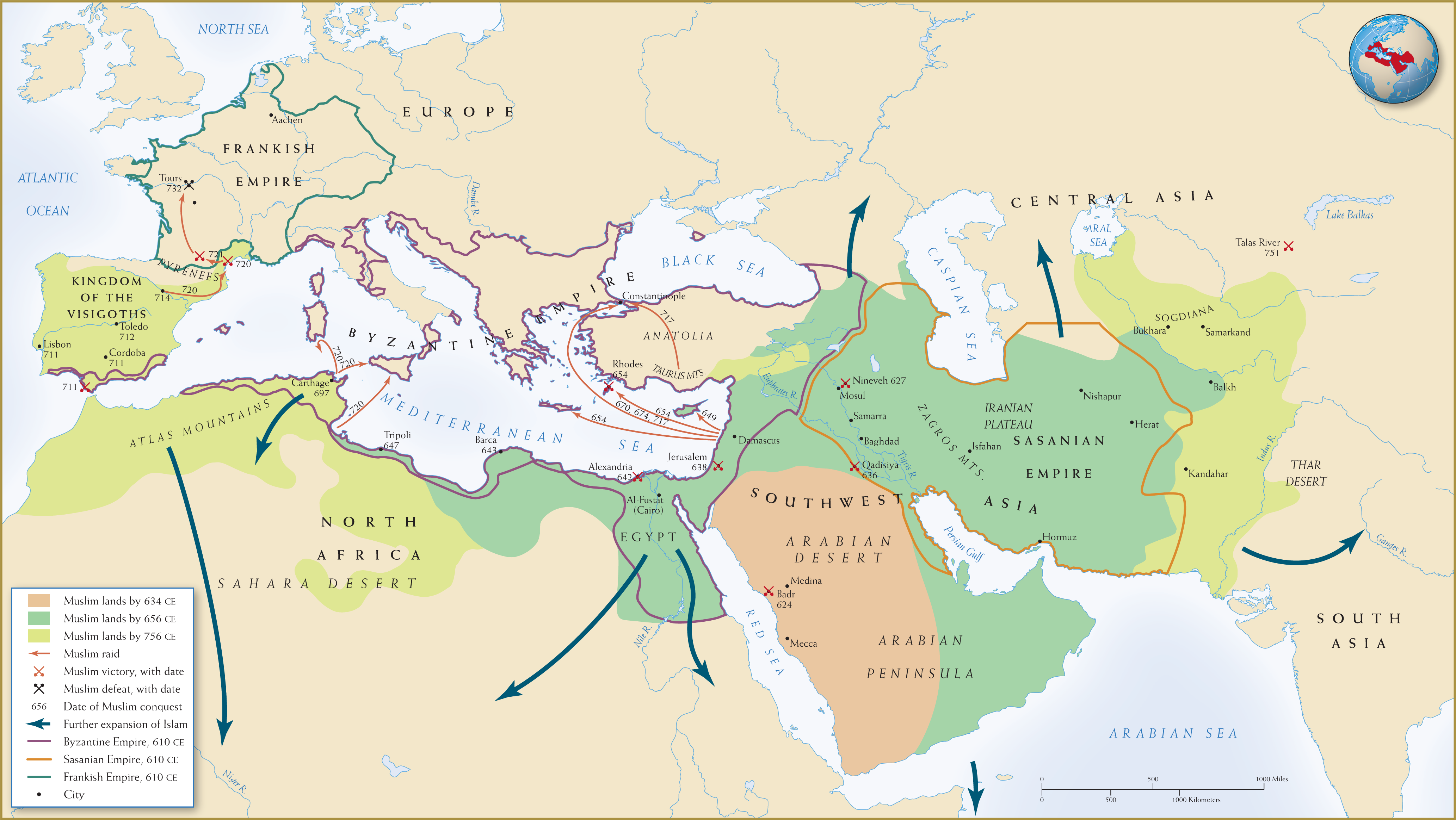

Map 2.1 The Spread of Islam during the First Millennium

Islam emerged in the Arabian Peninsula in the seventh century CE. Within 150 years, leaders of this religious community had conquered a vast amount of territory.

Muhammad’s relations with women reflected these changes. As a young man, he married a woman fifteen years his senior—Khadija, an independent trader—and took no other wives before she died. It was Khadija to whom he went in fear following his first revelations. She wrapped him in a blanket and assured him of his sanity. She was also his first convert. Later in life, however, he took younger wives, some of whom were widows of his companions, and insisted on their veiling (partly as a sign of their modesty and privacy). He married his favorite wife, Aisha, when she was only nine or ten years old. As a major source for collecting Muhammad’s sayings, Aisha became an important figure in early Islam.

By the time Islam reached Southwest Asia and North Africa, where strict gender rules and women’s subordinate status were entrenched, the newfaith was adopting a patriarchal outlook. Muslim men could divorce freely; women could not. A man could take four wives and numerous concubines; a woman could have only one husband. Well-to-do women, always veiled, lived secluded from male society. Still, the Quran did offer women some protections. Men had to treat each wife with respect if they took more than one. Women could inherit property (although only half of what a man inherited). Marriage dowries went directly to the bride rather than to her guardian, indicating women’s independent legal standing; and while a woman’s adultery drew harsh punishment, its proof required eyewitness testimony. The result was a legal system that reinforced men’s dominance over women but empowered magistrates to oversee the definition of male honor and proper behavior.

EVALUATE the relationships between religion, empire, and commercial exchange across Afro-Eurasia during this period.

The arts flourished during the Abbasid period, a blossoming that left its imprint throughout society. Within a century of Abbasid rule, Arabic had superseded Greek as the Muslim world’s preferred language for poetry, literature, medicine, science, and philosophy. Arabic spread beyond native speakers to become the language of the educated classes. Arabic scholars preserved and extended Greek and Roman thought, in part through the transmission of treatises by Aristotle, Hippocrates, Galen, Ptolemy, and Archimedes, among others. To house such manuscripts, patrons of the arts and sciences—including the caliphs—opened magnificent libraries.

The Muslim world absorbed scientific breakthroughs from China and other areas: Muslims incorporated the use of paper from China, adopted siege warfare from China and Byzantium, and assimilated knowledge of plants from the ancient Greeks. From Indian sources, scholars borrowed a numbering system based on the concept of zero and units of ten—what we today call Arabic numerals. Arab mathematicians were pioneers in arithmetic, geometry, algebra, and trigonometry. Since much of Greek science had been lost in the west and later was reintroduced via the Muslim world, the Islamic contribution to the West was of immense significance. Thus, this intense borrowing, translating, storing, and diffusing of ideas brought worlds together.

COMPARISON Compare the achievements of Muslim dynasties in Spain, Africa, and Central Asia.

As Islam spread and decentralized, it generated dazzling and often competitive dynasties in Spain, North Africa, and points farther east. Each dynastic state revealed the Muslim talent for achieving high levels of artistry far from its heartland. But growing diversity led to a problem: Islam fragmented politically. No single political regime could hold its widely dispersed believers together. (See Map 2.2.)

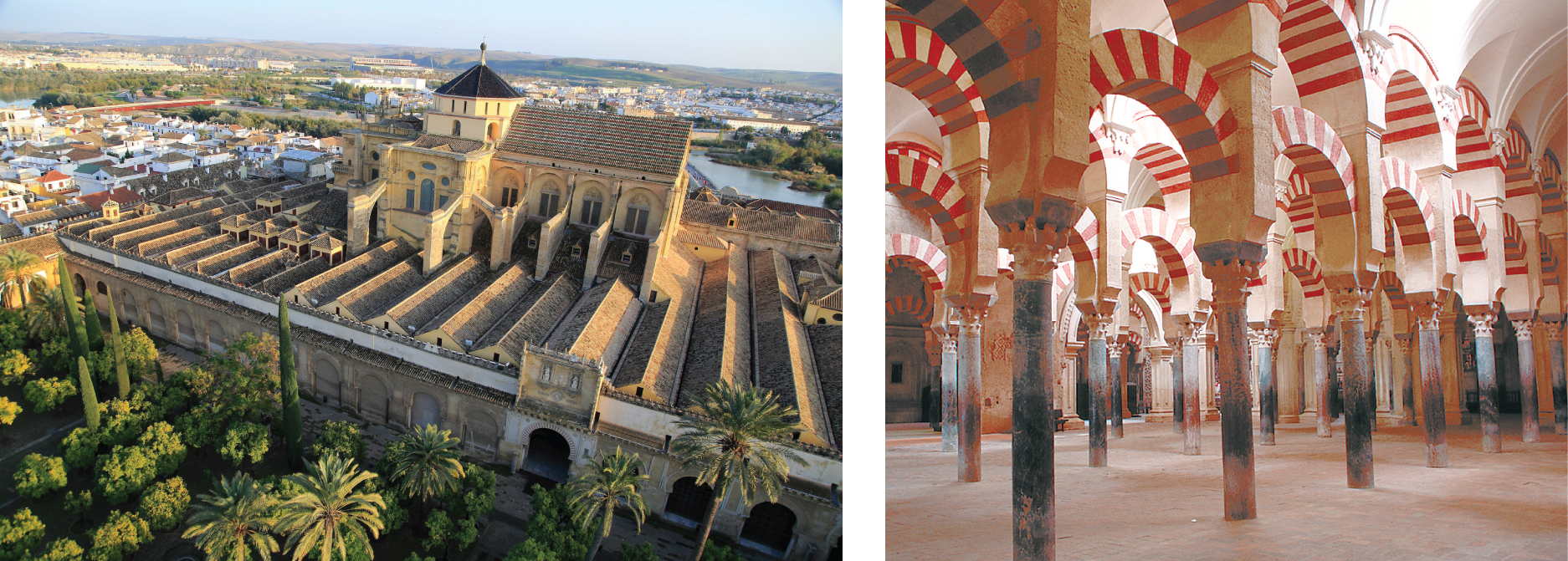

Cities in Spain One extraordinary Muslim state arose in Spain under Abd al-Rahman III (r. 912–961 CE), the successor ruler of a Muslim kingdom founded there over a century earlier. Abd al-Rahman brought peace and stability to a violent frontier region where civil conflict had disrupted commerce and intellectual exchange. His evenhanded governance promoted amicable relations among Muslims, Christians, and Jews, and his diplomatic relations with Christian potentates as far away as France, Germany, and Scandinavia generated impressive commercial exchanges between western Europe and North Africa. He expanded and beautified the capital city of Cordoba, and his successor made the Great Mosque of Cordoba one of Spain’s most stunning sites. In the nearby city Madinat al-Zahra, Abd al-Rahman III surrounded the city’s administrative offices and mosque with verdant gardens of lush tropical and semitropical plants, tranquil pools, fountains that spouted cooling waters, and sturdy aqueducts that carried potable water to the city’s inhabitants.

Talent in Central Asia In the eastern regions of the Islamic empire, Abbasid rulers in Baghdad surrounded themselves with learned men from Sogdiana, the central Asian territory where Greek learning had flourished. The Barmaki family, who for several generations held high administrative offices under the Abbasids, came from the central Asian city of Balkh. Loyal servants of the caliph, the Barmakis made sure that wealth and talent from the crossroads of Asia were funneled into Baghdad. Devoted patrons of the arts, the Barmakis promoted and collected Arabic translations of Persian, Greek, and Sanskrit manuscripts. They also encouraged central Asian scholars to enhance their learning by moving to Baghdad. These scholars included the Islamic cleric al-Bukhari (d. 870 CE), who was a renowned collector of hadith; the mathematician al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850 CE), who modified Indian digits into Arabic numerals and wrote the first book on algebra; and the philosopher al-Farabi (d. 950 CE), from a Turkish military family, who also made his way to Baghdad, where he studied eastern Christian teachings and promoted the Platonic ideal of a philosopher-king. Even when the Abbasid caliphate began to decline, intellectual vitality continued under the patronage of local rulers. The best example of this is, perhaps, the polymath Ibn Sina (known in the west as Avicenna; 980–1037), whose Canon of Medicine stood as the standard medical text in both Southwest Asia and Europe for centuries.

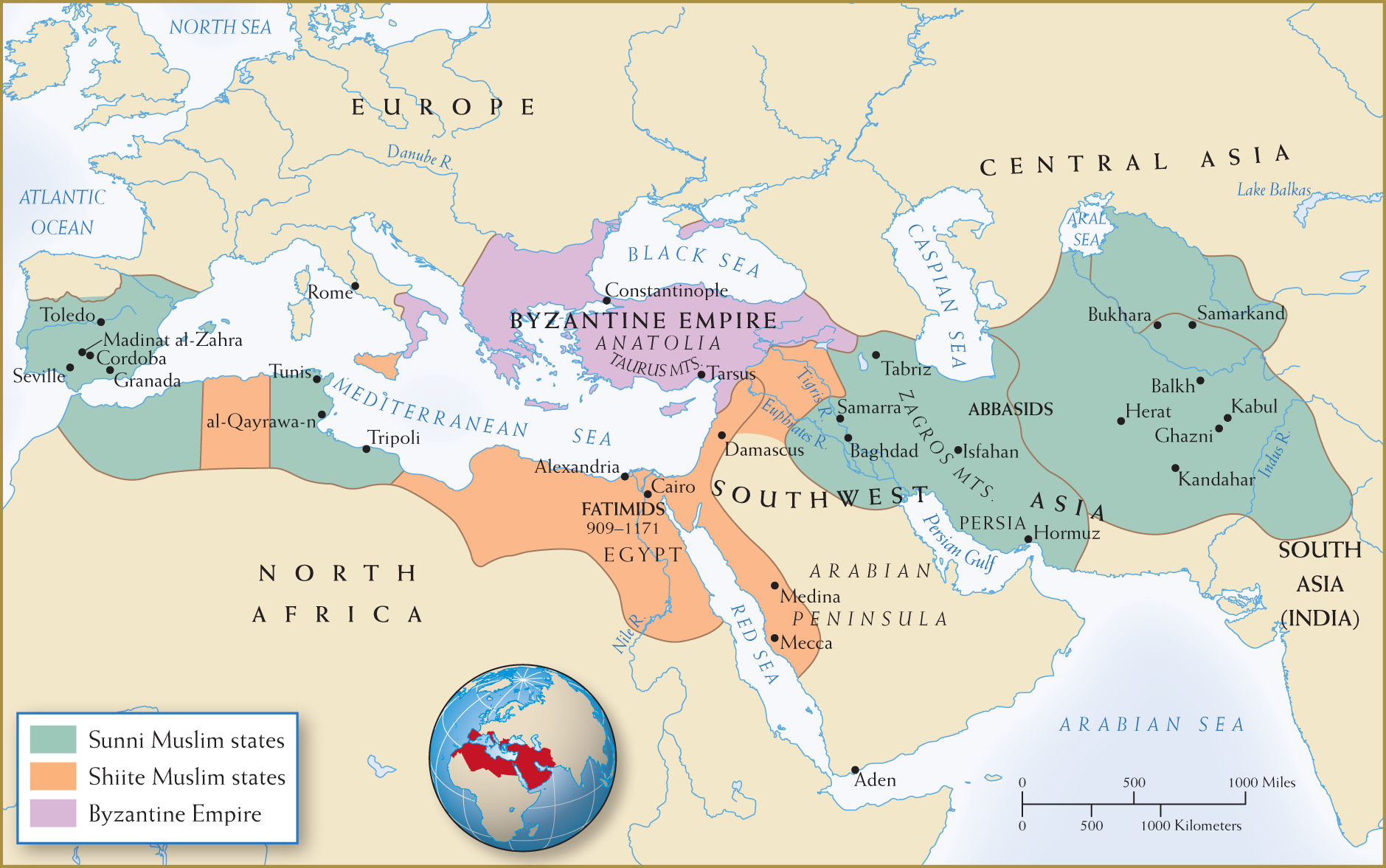

Map 2.2 Political Fragmentation in the Islamic World, 750–1000 CE

By 1000 CE, the Islamic world was politically fractured and decentralized. The Abbasid caliphs still reigned in Baghdad, but they wielded very limited political authority.

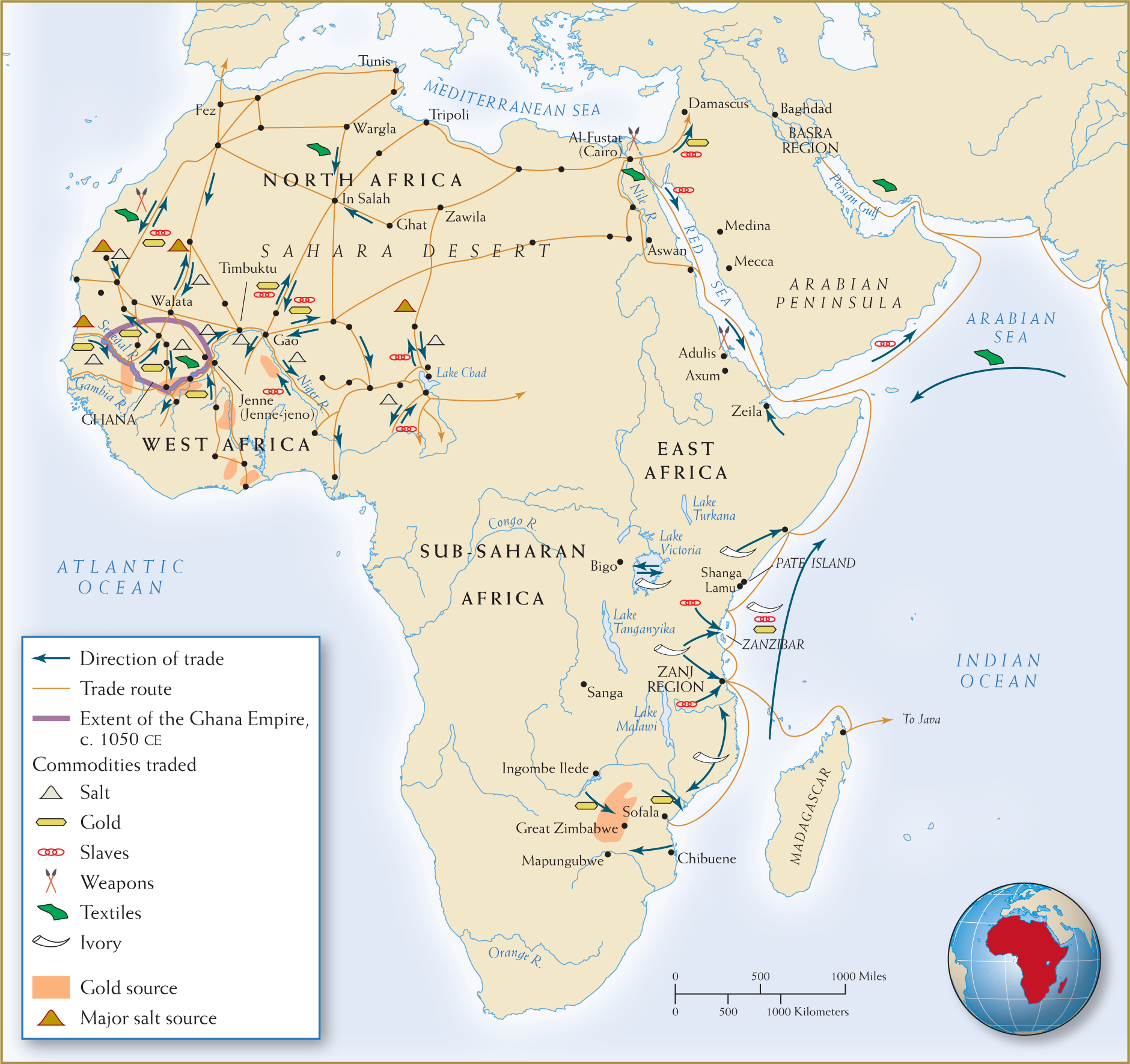

Trade in Sub-Saharan Africa Carried by traders and scholars, Islam also crossed the Sahara Desert and penetrated well into Africa, where merchants exchanged weapons and textiles for gold, salt, and slaves. (See Map 2.3.) Trade did more than join West Africa to North Africa. It generated prodigious wealth, which allowed centralized political kingdoms to develop. The most celebrated was Ghana, which lay at the terminus of North Africa’s major trading routes and was often hailed in Arab sources for its gold, as well as its pomp and power. Seafaring Muslim traders carried Islam into East Africa via the Indian Ocean. As early as the eighth century CE, coastal trading communities in East Africa were exporting ivory and possibly slaves. By the tenth century, the East African coast featured a mixed African-Arab culture. The region’s evolving Bantu language absorbed Arabic words and before long gained a new name, Swahili (derived from the Arabic plural of the word meaning “coast”).

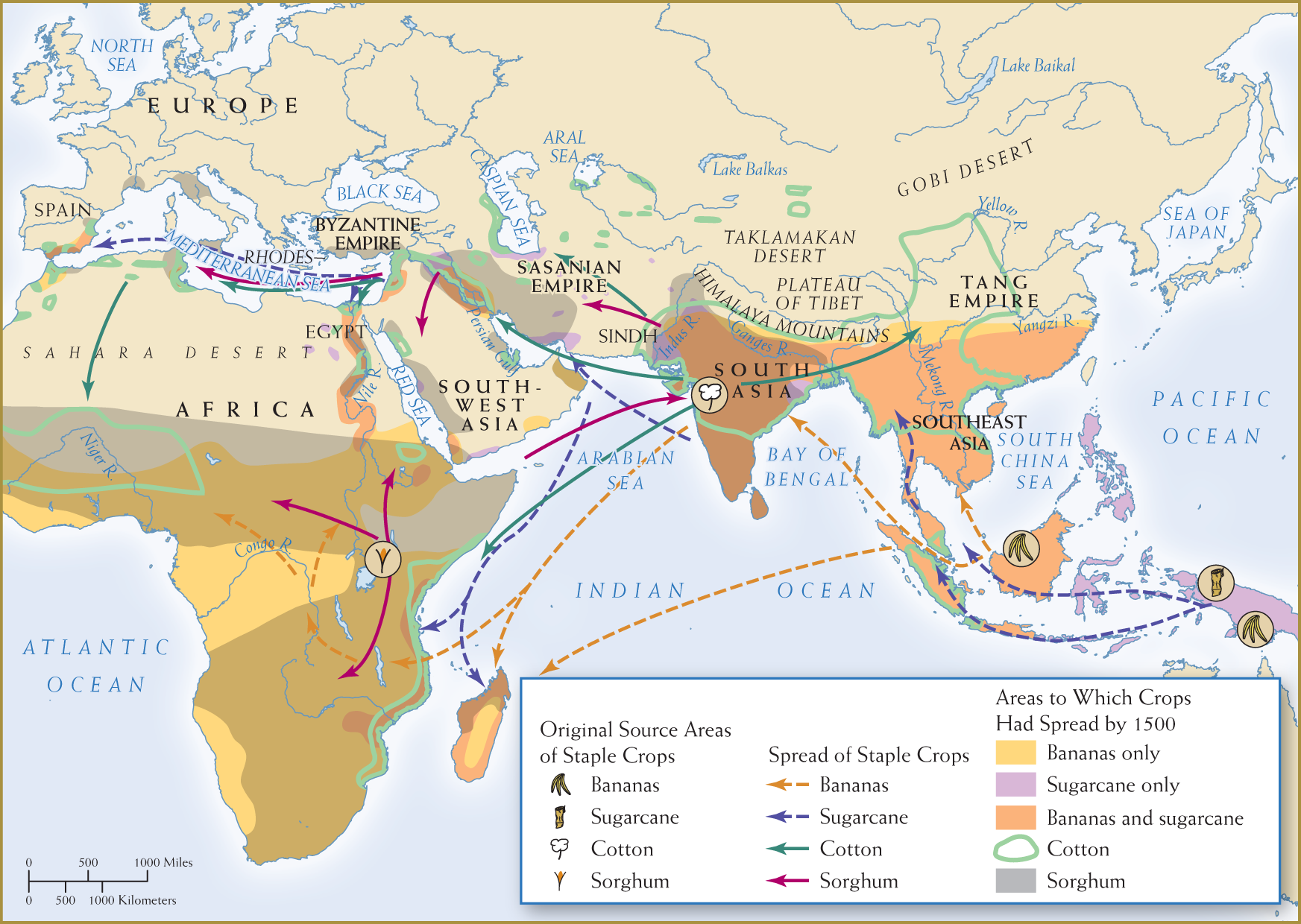

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE Explain what caused the spread of crops around the Islamic world? Why might it be called the “Green Revolution?”å

Green Revolution in the Islamic World New crops, especially food crops, leaped across political and cultural borders during this period, offering expanding populations more diverse and nutritious diets and the ability to feed increased numbers. Most of them originated in Southeast Asia, made their way to India, and dispersed throughout the Muslim world and into China. These crops included new strains of rice, taro, sour oranges, lemons, limes, and most likely coconut palm trees, sugarcane, bananas, plantains, and mangoes. Sorghum and possibly cotton and watermelons arrived from Africa.

Map 2.3 Islam and Trade in Sub-Saharan Africa, 700–1000 CE

Islamic merchants and scholars, not Islamic armies, carried Islam into sub-Saharan Africa. Trace the trade routes in Africa, being sure to follow the correct direction of trade.

Once Muslims conquered the Sindh in northern India in 711 CE, the crop innovations pioneered in Southeast Asia made their way to the west. Soon a “green revolution” in crops and diet swept through the Muslim world. Sorghum supplanted millet and the other grains of antiquity because it was hardier, had higher yields, and required a shorter growing season. Citrus trees added flavor to the diet and provided refreshing drinks during the summer heat. Increased cotton cultivation led to a greater demand for textiles.

For over 300 years, farmers from northwest India to Spain, Morocco, and West Africa made impressive use of the new crops. They increased agricultural output, slashed fallow periods, and grew as many as three crops on lands that formerly had yielded one. (See Map 2.4.) As a result, farmers could feed larger communities. Even as cities grew, the countryside became more densely populated and more productive.

Islam’s whirlwind rise generated internal tensions from the start. It is hardly surprising that a religion that extolled territorial conquests and created a large empire in its first decades would also spawn dissident religious movements that challenged the existing imperial structures. Muslims shared a reverence for a basic text and a single God but often had little else in common. Religious and political divisions only grew deeper as Islam spread into new corners of Afro-Eurasia.

COMPARISON Compare the beliefs of the Sunni and Shia Muslims.

Sunnis and Shiites Early division within Islam was fueled by disagreements about who should succeed the Prophet, how the succession should take place, and who should lead Islam’s expansion into the wider world. Sunnis (from the Arabic word meaning “tradition”) accepted that the political succession from the Prophet to the four “rightly guided caliphs” and then to the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties was the correct one. The vast majority of Muslims today are Sunni. Dissidents, like the Shiites, contested the Sunni understanding of political and spiritual authority. Shiites (“members of the party of Ali”) felt that the proper successors should have been Ali, who had married the Prophet’s daughter Fatima, and then his descendants. Ali was one of the early converts to Islam and one of the band of Meccans who had migrated with the Prophet to Medina. The fourth of the “rightly guided caliphs,” he ruled over the Muslim community from 656 to 661 CE, dying at the hands of an assassin who struck him down as he was praying in a mosque in Kufa, Iraq. Shiites believed that Ali’s descendants, whom they called imams, had religious and prophetic power as well as political authority—and thus should be spiritual leaders.

Early Religious Divisions

Early Religious Divisions

Map 2.4 Agricultural Diffusion in the First Millennium

The second half of the first millennium saw a revolution in agriculture throughout Afro-Eurasia. Agriculturalists across the landmass increasingly cultivated similar crops.

Shiism appealed to regional and ethnic groups whom the Umayyads and Abbasids had excluded from power; it became Islam’s most potent dissident force and created a permanent divide within Islam. Shiism was well established in the first century of Islam’s existence, and over time the Sunnis and Shiites diverged even more than these early political disputes over succession might have indicated. Both groups had their own versions of the sharia, their own collections of hadith, and their own theological tenets.

The Fatimids Repressed in what is present-day Iraq and Iran, Shiite activists made their way to North Africa, where they joined with dissident Berber groups to topple several rulers. In 909 CE, a Shiite religious and military leader, Abu Abdallah, overthrew the Sunni ruler there. Thus began the Fatimid regime.

After conquering Egypt in 969 CE, the Fatimids set themselves against the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad, refusing to acknowledge their legitimacy and claiming to speak for the whole Islamic world. The Fatimid rulers established their capital at al-Qahira (or Cairo). Early on they founded al-Azhar Mosque, which attracted scholars from all over Afro-Eurasia and spread Islamic learning outward. They also built other elegant mosques and centers of learning. The Fatimid regime lasted until the late twelfth century, though its rulers made little headway in persuading the Egyptian population, most of whom remained Sunnis, to embrace their Shiite beliefs.

COMPARISON Compare Christianity and Islam’s universalizing tendencies and their connection to state power.

By 1000 CE Islam, which had originated as a radical religious revolt in a small corner of the Arabian Peninsula, had grown into a vast political and religious empire. It had become the dominant force in the middle regions of Afro-Eurasia. Like its rival in this part of the world, Christianity, it aspired to universality. But unlike Christianity, it was linked from its outset topolitical power. Muhammad and his early followers created an empire to facilitate the expansion of their faith, while their Christian counterparts inherited an empire when Constantine embraced the new faith. A vision of a world under the jurisdiction of Muslim caliphs, adhering to the dictates of the sharia, drove Muslim armies, merchants, and scholars to territories thousands of miles away from Mecca and Medina. Yet as Islam’s reach stretched thin, political fragmentation within the Muslim world meant that Islam’s reach could not extend to much of western Europe and China.