INTERVIEW WITH ASHA RANGAPPA

The Sociological Imagination

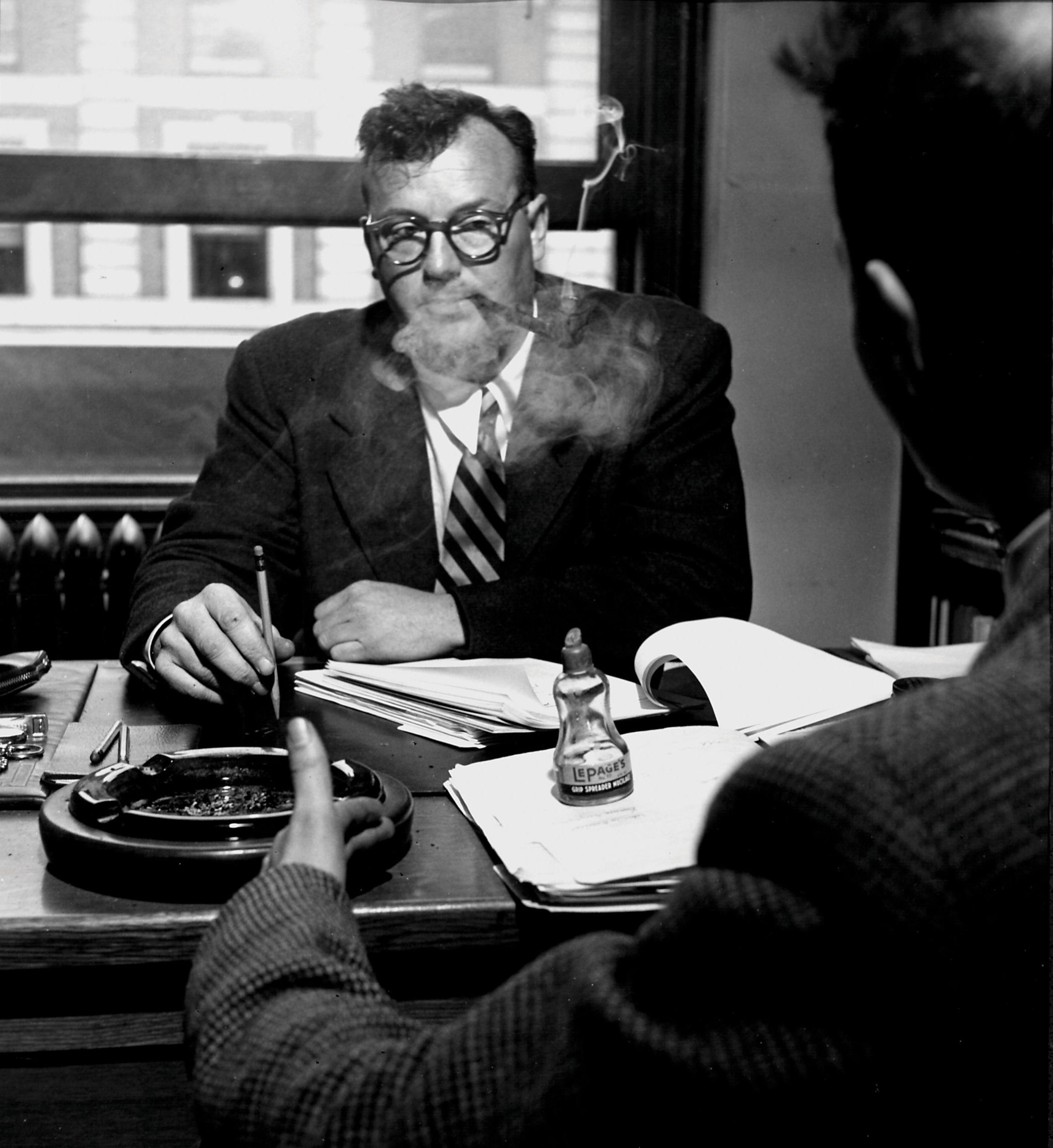

Sociologist C. Wright Mills smoking his pipe in his office at Columbia University. How does Mills’s concept of sociological imagination help us make the familiar strange?

Sociologist C. Wright Mills smoking his pipe in his office at Columbia University. How does Mills’s concept of sociological imagination help us make the familiar strange?More than 50 years ago, sociologist C. Wright Mills argued that in the effort to think critically about the social world around us, we need to use our sociological imagination, the ability to see the connections between our personal experience and the larger forces of history. This is just what we are doing when we question this textbook, this course, and college in general. In The Sociological Imagination (1959), Mills describes it this way: “The first fruit of this imagination—and the first lesson of the social science that embodies it—is the idea that the individual can understand his own experience and gauge his own fate only by locating himself within his period, that he can know his own chances in life only by becoming aware of those of all individuals in his circumstances. In many ways it is a terrible lesson; in many ways a magnificent one.” The terrible part of the lesson is to make our own lives ordinary—that is, to see our intensely personal, private experience of life as typical of the period and place in which we live. This can also serve as a source of comfort, however, helping us realize we are not alone in our experiences, whether they involve our alienation from the increasingly dog-eat-dog capitalism of modern America, the peculiar combination of intimacy and dissociation that we may experience on the internet, or the ways that nationality or geography affect our life choices. The sociological imagination does not just leave us hanging with these feelings of recognition, however. Mills writes that it also “enables [us] to take into account how individuals, in the welter of their daily experience, often become falsely conscious of their social positions.” The sociological imagination thus allows us to see the veneer of social life for what it is and to step outside the “trap” of rapid historical change in order to comprehend what is occurring in our world and the social foundations that may be shifting right under our feet. As Mills wrote after World War II, a time of enormous political, social, and technological change, “The sociological imagination enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society. That is its task and its promise. To recognize this task and this promise is the mark of the classic social analyst.”

Mills offered his readers a way to stop and take stock of their lives in light of all that had happened in the previous decade. Of course, we almost always feel that social change is fairly rapid and continually getting ahead of us. Think of the 1960s or even today, with the rise of the internet and global terror threats. In retrospect, we consider the 1950s, the decade when Mills wrote his seminal work, to be a relatively placid time, when Americans experienced some relief from the change and strife of World War II and the Great Depression. But Mills believed the profound sense of alienation experienced by many during the postwar period was a result of the change that had immediately preceded it.

HOW TO BE A SOCIOLOGIST ACCORDING TO QUENTIN TARANTINO: A SCENE FROM PULP FICTION

Have you ever been to a foreign country, noticed how many little things were different, and wondered why? Have you ever been to a church of a different denomination—or a different religion altogether—from your own? Or have you been a fish out of water in some other way? The only guy attending a social event for women, perhaps? Or the only person from out of state in your dorm? If you have experienced that fish-out-of-water feeling, then you have, however briefly, engaged your sociological imagination. By shifting your social environment enough to be in a position where you are not able to take everything for granted, you are forced to see the connections between particular historical paths taken (and not taken) and how you live your daily life. You may, for instance, wonder why there are bidets in most European bathrooms and not in American ones. Or why people waiting in lines in the Middle East typically stand closer to each other than they do in Europe or America. Or why, in some rural Chinese societies, many generations of a family sleep in the same bed. If you are able to resist your initial impulses toward xenophobia (feelings that may result from the discomfort of facing a different reality), then you are halfway to understanding other people’s lifestyles as no more or less sensible than your own. Once you have truly adopted the sociological imagination, you can start questioning the links between your personal experience and the particulars of a given society without ever leaving home.

In the following excerpt of dialogue from Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 film Pulp Fiction, the character Vincent tells Jules about the “little differences” between life in the United States and life in Europe.

VINCENT: It’s the little differences. A lotta the same shit we got here, they got there, but there they’re a little different.

JULES: Example?

VINCENT: Well, in Amsterdam, you can buy beer in a movie theater. And I don’t mean in a paper cup either. They give you a glass of beer, like in a bar. In Paris, you can buy beer at McDonald’s. Also, you know what they call a Quarter Pounder with Cheese in Paris?

JULES: They don’t call it a Quarter Pounder with Cheese?

VINCENT: No, they got the metric system there, they wouldn’t know what the fuck a Quarter Pounder is.

JULES: What’d they call it?

VINCENT: Royale with Cheese.

VINCENT: [Y]ou know what they put on french fries in Holland instead of ketchup?

JULES: What?

VINCENT: Mayonnaise. [. . .] And I don’t mean a little bit on the side of the plate, they fuckin’ drown ’em in it.

JULES: Uuccch!

Vincent Vega (John Travolta) describes his visit to a McDonald’s in Amsterdam to Jules Winnfield (Samuel L. Jackson).

Vincent Vega (John Travolta) describes his visit to a McDonald’s in Amsterdam to Jules Winnfield (Samuel L. Jackson).Your job as a sociologist is to get into the mind-set that mayonnaise on french fries, though it might seem disgusting at first, is not strange after all, certainly no more so than ketchup.

Another way to think about the sociological imagination is to ask ourselves what we take to be natural that actually isn’t. For example, let’s return to the question “Why go to college?” Sociologists and economists have shown that the financial benefits of education—particularly higher education—appear to be increasing. They refer to this as the “returns to schooling.” In today’s economy, the median (i.e., typical) annual income for full-time workers ages 25 to 37 with a high-school degree is $31,000; for those with a bachelor’s degree, it is $56,000 (Pew Research, 2019). That $25,000 annual advantage seems like a good deal, but is it really? Let’s shift gears and do a little math.

WHAT ARE THE TRUE COSTS AND RETURNS OF COLLEGE?

Now that you are thinking like a sociologist, let’s compare the true cost of going to college for four or five years to calling the whole thing off and taking a full-time job right after high school. First, there is the tuition to consider. Let’s assume for the sake of argument that you are paying $10,116 per year for tuition (Powell & Kerr, 2019). That’s a lot less than what most private four-year colleges cost, but about average for in-state tuition at a state school.

Using a standard formula to adjust for inflation and bring future amounts into current dollars, we can determine that paying out $10,116 this year and slightly higher amounts over the next three years (assuming a 3.3 percent annual rise in tuition and a corresponding discount rate) is equivalent to paying about $40,500 in one lump sum today; this would be the direct cost of attending college. Indirect costs—so-called opportunity costs—exist as well, such as the costs associated with the amount of time you are devoting to school. Taking into account the typical wage for a high-school graduate, we can calculate that if you worked full-time instead of going to college, you would make $30,000 this year. Thus we find that the present value of the total wages lost over the next four years by choosing full-time school over full-time work is about $144,000. Add these opportunity costs to the direct costs of tuition, and we get $184,500.

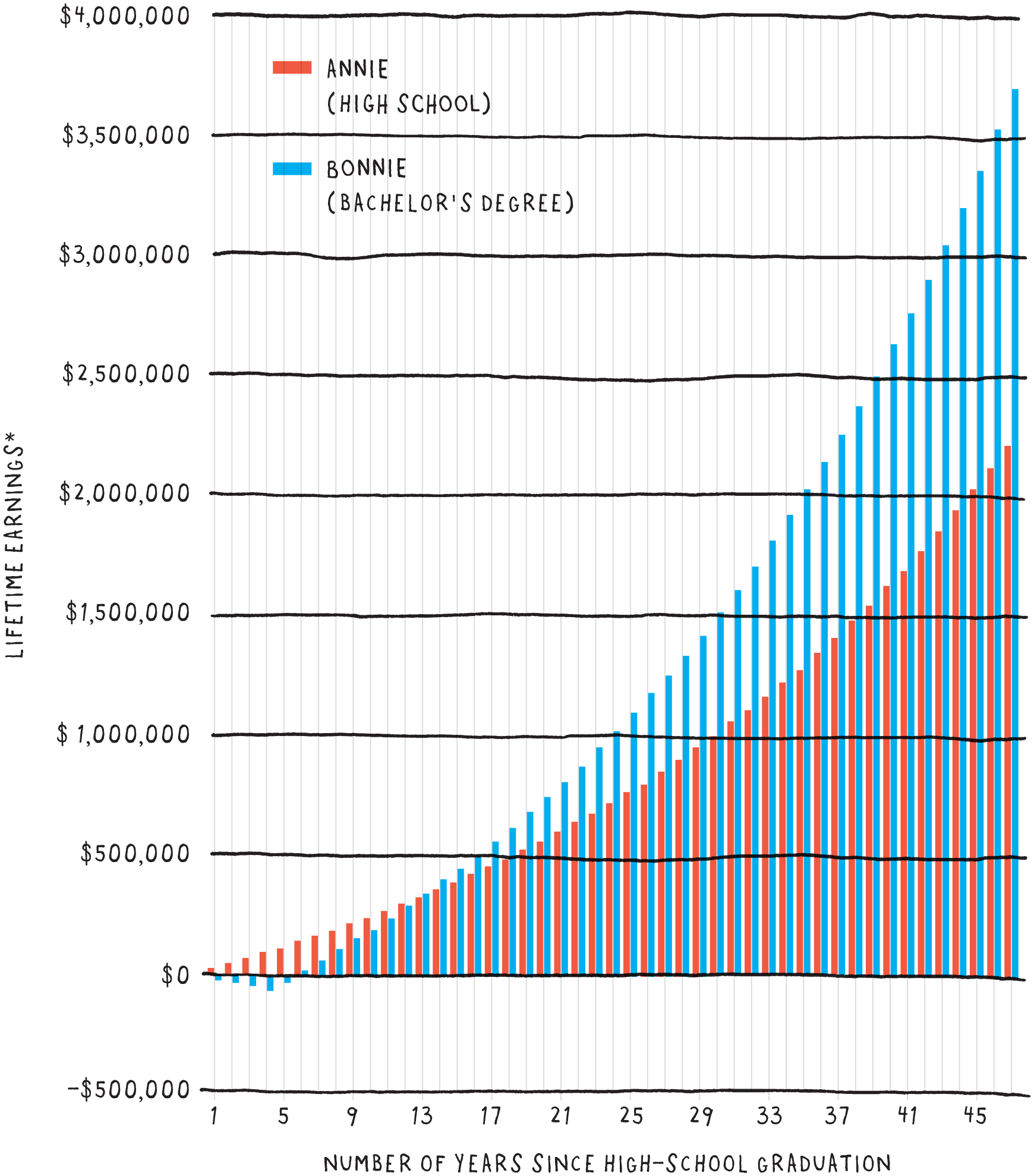

Next we need to calculate the “returns to schooling.” For the sake of simplicity, we will regard the $56,000 annual earnings figure for recent college graduates as fixed for the first 10 years past college graduation. We will use a higher estimate for annual earnings after that, to take into account the fact that mid-career workers make more. But remember, those who start working right out of high school begin earning about five years earlier than those who spend that time in college (the average time it takes to complete a bachelor’s degree at a public university is 5.2 years [Shapiro et al., 2016]). Assuming you retire at age 65, you will have worked 42 years (high-school grads will be in the workforce for 47 years because of that 5-year head start). However, given your higher average earnings per year of work, when we compare your lifetime earnings to the lifetime earnings of someone who has only a high-school education, we find that with a college degree you will make about $1,500,000 more than someone who went straight to work after high school (Figure 1.1). On top of this substantial financial return to schooling, research also shows that earning a high-school and/or college degree makes us healthier and less likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors like smoking, even after accounting for other factors like income (Heckman et al., 2016).

Two famous college dropouts. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg (left) attended Harvard but dropped out before graduating. Oprah Winfrey (right) left Tennessee State University as a sophomore to begin a career in media.

Two famous college dropouts. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg (left) attended Harvard but dropped out before graduating. Oprah Winfrey (right) left Tennessee State University as a sophomore to begin a career in media.But wait a minute: How do we know for sure that college really mattered in the equation? Individuals who finish college might earn more because they actually learned something and obtained a degree, or—a big OR—they might earn more regardless of the college experience because people who stay in school (1) are innately smarter, (2) know how to work the system, (3) come from wealthier families, (4) can delay gratification, (5) are more efficient at managing their time, or (6) all of the above—take your pick. In other words, State U. graduates might not have needed to go to college to earn higher wages; they might have been successful anyway.

Maybe, then, the success stories of Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs, Lady Gaga, and other college dropouts don’t cut against the grain so sharply after all. Maybe they were the savvy ones: Convinced of their ability to make it on their own, thanks to the social cues they received (including the fact that they had been admitted to college), they decided that they wouldn’t wait four years to try to achieve success. They opted to just go for it right then and there. College’s “value added,” they might have concluded, was marginal at best.

*This set of hypothetical women—Annie and Bonnie—live in a world that is not quite like reality. We did not flatten Annie’s trajectory to account for the fact that high-school diploma holders are more likely to experience periods of forced part-time work and/or unemployment. We also assumed the same rate of income increase over time (i.e., raises) for these two, although high-school diploma holders are more likely to experience wage stagnation than college diploma holders.

SOURCE: Carnevale et al., 2014.

GETTING THAT "PIECE OF PAPER"

Even if college turns out to matter in the end, does it make a difference because of the learning that takes place there or because of our credentialist society that it aids and abets? The answer to this question has enormous implications for what education means in our society. Imagine, for example, a society in which people become doctors not by doing well on the SATs, going to college, taking premed courses, acing the MCATs, and then spending more time in the classroom. Instead, the route to becoming a doctor—among the most prestigious and highly paid occupations in our society—starts with emptying bedpans as a nurse’s aide and working your way up through the ranks of registered nurse, apprentice physician, and so forth; finally, after years of on-the-job training, you achieve the title of doctor. Social theorist Randall Collins has proposed just such a medical education system in the controversial The Credential Society: A Historical Sociology of Education and Stratification (1979), which argues that the expansion of higher education has merely resulted in a ratcheting up of credentialism and expenditures on formal education rather than reflecting any true societal need for more formal education or opening up opportunities to more people.

College bulletin boards are covered with advertisements like this one promoting websites that generate diplomas. Why are these fake diplomas not worth it?

College bulletin boards are covered with advertisements like this one promoting websites that generate diplomas. Why are these fake diplomas not worth it?If Collins is correct and credentials are what matter most, then isn’t there a cheaper, faster way to get them? In fact, all you need are $29.95 and a little guts, and you can receive a diploma from one of the many online sites that promise either legitimate degrees from nonaccredited colleges or a faux college diploma from any school of your choosing. Thus why not save four years and lots of money and obtain your credentials immediately?

Obviously, universities have incentives to prevent such websites from undermining their exclusive authority over conferring degrees. They rely on a number of other social institutions, ranging from copyright law to magazines that publish rankings to protect their status. Despite universities’ interest in protecting their reputations, I had never had a university employer verify my education claims when applying to teach until 2015 when I moved to Princeton. Every other employer, including NYU, accepted my résumé without calling my graduate or undergraduate universities. NYU does check to make sure student applicants have completed high school, however. Are universities too lazy to care? Probably not.

Table 1.1 Overcredentialed? Workers with Bachelor’s Degrees in 1970 and 2015

|

PERCENTAGE OF WORKFORCE, AGES 25–64, WITH BACHELOR'S DEGREE |

|||

|

JOB Title |

1970 |

2015 |

% CHANGE |

|

Bartenders |

3% |

20% |

567% |

|

Photographers |

10% |

50% |

400% |

|

Electricians |

2% |

7% |

250% |

|

Accountants and auditors |

42% |

78% |

86% |

|

Actors, directors, and producers |

41% |

74% |

80% |

|

Writers and authors |

47% |

84% |

79% |

|

Military personnel |

24% |

37% |

54% |

|

Dental hygienists |

29% |

36% |

24% |

|

Primary-school teachers |

84% |

94% |

12% |

|

Doctors |

96% |

99% |

3% |

|

Preschool teachers |

53% |

48% |

–9% |

|

Human-resource clerks |

40% |

29% |

–28% |

|

Machine programmers |

27% |

7% |

–74% |

A recent article in The Economist found that since the 1970s, more American workers in most professions have earned a bachelor’s degree. In half of these professions, the authors found that real wages have actually fallen. Do these examples support Collins’s argument about overcredentialism? Have these jobs gotten more demanding or technologically complex over time, or are there just more people doing them with a diploma?

SOURCES: University of Minnesota IPUMS; The Economist (2018a).

There are strong informal mechanisms by which universities protect their status. First, there is the university’s alumni network. Potential employers rarely call a university’s registrar to make sure you graduated, but they will expect you to talk a bit about your college experience. If your interviewer is an alumnus/alumna or otherwise familiar with the institution, you might also be expected to talk about what dorm you lived in, reminisce about a particularly dramatic homecoming game, or gripe about an especially unreasonable professor. If you slip up on any of this information, suspicions will grow, and then people might call to check on your graduation status. Perhaps there are some good reasons not to opt for that $29.95 degree and to pay the costs of college after all.

On a more serious note, the role of credentialism in our society means that getting in—especially to a wealthy school with plenty of need-based aid available—can make a huge difference for lower-income students. I sat down with Asha Rangappa, the dean of admissions at Yale Law School (and former FBI agent), who explained that by the time students are old enough to apply to law school, middle-class and upper-class students have already been granted all sorts of opportunities that make them appear to be stronger candidates even if they do not have better moral character or a stronger aptitude for law than their less affluent counterparts in the same applicant pool:

I read anywhere from three thousand, four thousand applications a year, and I do a kind of character and personality assessment. I decide who gets in. . . . I think that there’s a meritocracy at the point where I’m doing it, but I think accessing the good opportunities that allow you to take advantage of the meritocracy is limited. I think that’s the problem, I think that’s what somebody like me in my position works very hard to correct for. When twenty-two to twenty-five years of someone’s life are behind them, it is too late to correct the disparity in access that really needed to have been corrected from like zero to five years, zero to ten years.

Do I think that people who have had access to more resources and opportunities and money are going to do better in the admissions process? Yeah. Because they’re just going to have the richer background. And [admissions counselors] have to be able to be in a position where [we] can afford to account for that and take the risk. (Conley, 2015a)

What’s more, law schools’ rankings in magazines like US News and World Report are impacted by the average LSAT scores of their incoming classes. Rangappa’s school, Yale, is so elite that it is able to maintain its ranking even if its average LSAT score drops a little. But for other schools, a drop in LSAT scores will cause their ranking to drop, leading to a decline in high-quality applicants and a further drop in rankings. From Rangappa’s perspective:

I’ve now read over ten years, over thirty thousand admission files. To me, the LSAT is one number, and I can look at the rest of the file. There may very well be somebody who has a crappy LSAT score, but . . . I can tell in the totality of the application that the applicant is going to be a better person at the school. I have the luxury of taking that person because it’s Yale Law School and the way the US News formula is created, we’re not going to suffer a consequence if our median LSAT drops one point.

Rangappa’s account shows that elite educational institutions perform a balancing act whereby they often seek to broaden the population who gains from the opportunities and status they provide while at the same time maintaining their own rank in the hierarchy of similar institutions. That is, even when such institutions do want to level the playing field, they themselves are trapped in a highly competitive environment that does not allow them to fully counteract preexisting inequalities. Social institutions thus have a tendency to reinforce existing social structures and the inequalities therein. College (and graduate school) is no exception.

Glossary

- SOCIOLOGICAL IMAGINATION

- the ability to connect the most basic, intimate aspects of an individual’s life to seemingly impersonal and remote historical forces.