▶ ANIMATION: How It Works

The evolving concept of federalism

TRACE THE MAJOR SHIFTS IN STATE AND FEDERAL GOVERNMENT POWER OVER TIME

The nature of federalism has changed as the size and functions of the national and state governments have evolved. In the first century of our nation’s history, the national government played a relatively limited role and the boundaries between the levels of government were distinct. As the national government took on more power in the twentieth century, intergovernmental relations became more cooperative and the boundaries less distinct. Even within this more cooperative framework, federalism remains a source of conflict within our political system, both because the levels of government share lawmaking authority and because they may disagree over the details of government policy.

The early years

As the United States gained its footing, clashes between the advocates of state-centered and nation-centered federalism turned into a partisan struggle. The Federalists—the party of George Washington, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton—controlled the new government for its first 12 years and favored strong national power. One of their strongest allies was Chief Justice John Marshall, who wrote several landmark Supreme Court decisions that enhanced the power of the national government. The Federalists’ opponents, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, favored state power, or, as it came to be known, dual federalism. Dual federalism, as we will discuss, was the guiding principle of Marshall’s successor as chief justice, Roger Taney. Table 3.1 highlights several important decisions resolved during Marshall’s and Taney’s tenures on the Court.

TABLE 3.1

TABLE 3.1

Early Landmark Supreme Court Decisions on Federalism

|

Case |

Holding and significance for states’ rights |

Direction of the decision |

|

Chisholm v. Georgia (1793) |

Held that citizens of one state could sue another state; led to the Eleventh Amendment, which prohibited such lawsuits. |

Less state power |

|

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) |

Upheld the national government’s right to create a bank and reaffirmed the idea of “national supremacy.” |

Less state power |

|

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) |

Held that Congress, rather than the states, has broad power to regulate interstate commerce. |

Less state power |

|

Barron v. Baltimore (1833) |

Endorsed a notion of “dual federalism” in which the rights of a U.S. citizen under the Bill of Rights did not apply to that same person under state law. |

More state power |

|

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) |

Sided with southern states’ view that enslaved people were property and ruled that the Missouri Compromise violated the Fifth Amendment, because making slavery illegal in some states deprived owners of enslaved people of property. Contributed to the start of the Civil War. |

More state power |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Establishing National Supremacy The first confrontation came when the Federalists established a national bank in 1791, followed by a second national bank in 1816. At that time, the state of Maryland, which was controlled by the Democratic-Republicans, tried to tax the National Bank’s Baltimore branch out of existence. However, the bank refused to pay the tax, creating a conflict that sent the case to the Supreme Court. In the landmark decision McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), Marshall’s Court held that even though the word “bank” does not appear in the Constitution, Congress’s power to create one is implied through its relevant enumerated powers—such as the power to coin money, levy taxes, and borrow money. The Court also ruled that Maryland did not have the right to tax the bank because of the Constitution’s national supremacy clause.

A few years later, Marshall’s Court held in Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) that Congress has broad power to regulate interstate commerce. The ruling struck down a New York law that had granted a monopoly to a private company that was operating steamboats on the Hudson River between New York and New Jersey. By granting this monopoly, New York was interfering with interstate commerce, a power reserved to Congress by the Constitution. Even in the modern era, this ruling underlies many of the federal government’s regulations on businesses, which are based on the expectation that virtually any commercial activity will involve buying and selling across state lines.

In the early 1800s, the Supreme Court confirmed the national government’s right to regulate commerce between the states. The state of New York granted a monopoly to a ferry company serving ports in New York and New Jersey, but this was found to interfere with interstate commerce and was therefore subject to federal intervention.

In the early 1800s, the Supreme Court confirmed the national government’s right to regulate commerce between the states. The state of New York granted a monopoly to a ferry company serving ports in New York and New Jersey, but this was found to interfere with interstate commerce and was therefore subject to federal intervention.

The emergence of states’ rights and dual federalism

Under Marshall’s successor, Chief Justice Roger Taney, Court decisions involving federalism shifted to reflect a new concept: dual federalism. According to the system of dual federalism, the national and state governments are considered distinct, with little overlap in their activities or the services they provide. In this view, the national government’s activities are confined to powers strictly enumerated in the Constitution.

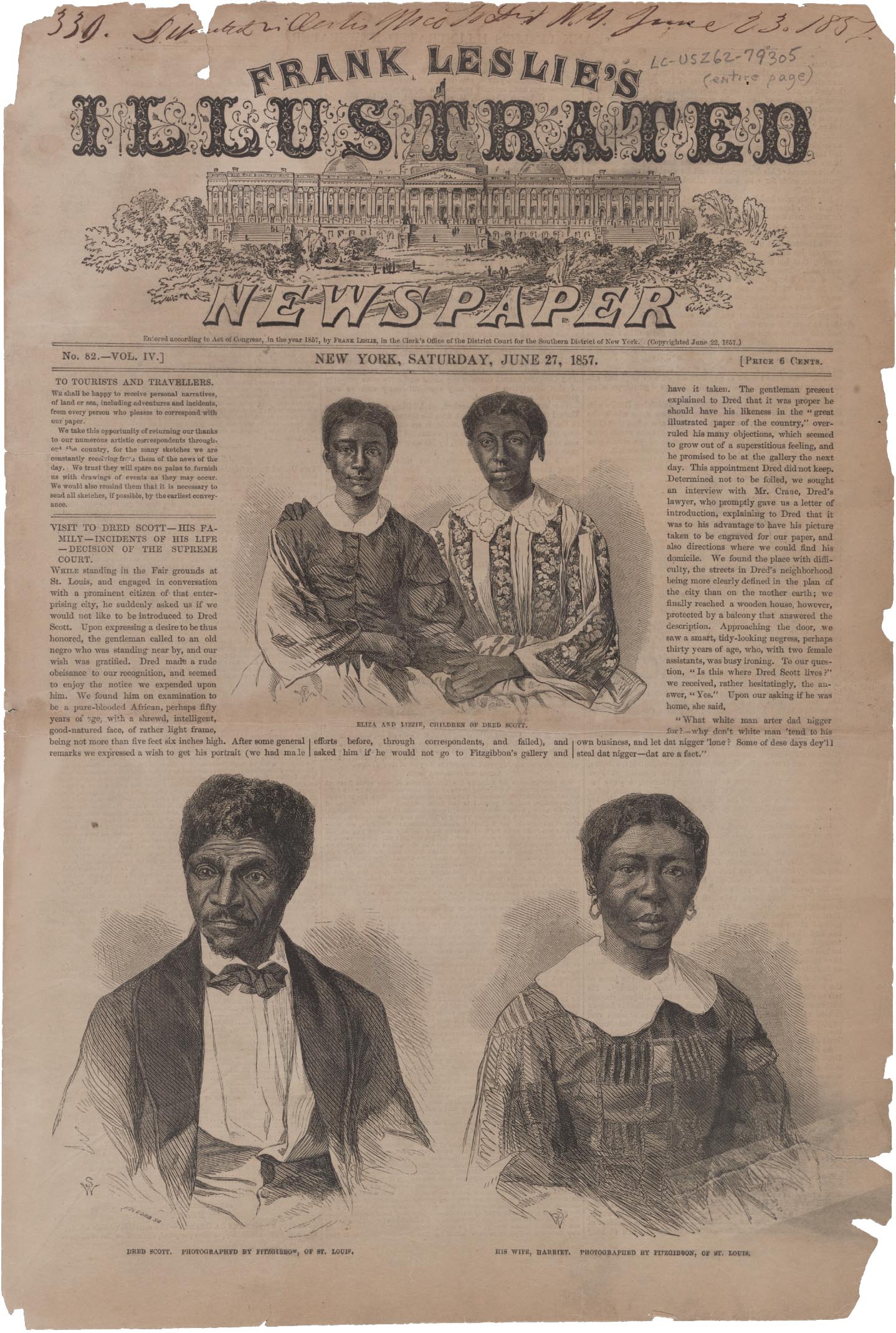

Dual federalism was expressed most consequentially in the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision of 1857. Dred Scott was an enslaved man who had lived for many years with his owner in the free state of Illinois and the free Wisconsin Territory but was living in Missouri, a state that allowed slavery, when his owner died. Scott petitioned for his freedom under the Missouri Compromise, which had made slavery illegal in any free state. The Court did not grant Scott his freedom. Its majority decision held that enslaved people were not citizens but private property; therefore, the Missouri Compromise’s ban on slavery in certain territories violated the Fifth Amendment because it deprived citizens (owners of enslaved people) of their property without the due process of law. Put another way, the Dred Scott decision said that state law, not federal, determined the legal status of enslaved people.

Contrasting Marshall’s decisions in favor of national power with Taney’s decisions in favor of state power highlights the profound policy consequences of judicial decisions. The Taney Court’s decision that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional is consistent with a dual federalism interpretation of the Constitution—but it also sustained the legality of slavery in southern states and halted attempts by representatives from the North to limit the spread of slavery into the western territories. There is no doubt that Taney favored this outcome on policy grounds. In this way, debates about dual federalism during this time were really about the legality of slavery, its expansion into new states, and the rights of formerly enslaved people in free states.

Arguments about dual federalism are sometimes framed using the concept of states’ rights: the idea that states retain some powers under the Constitution (specifically those reserved by the Tenth Amendment) and can ignore federal policies that encroach on these powers. The key question is, where does federal authority end and state authority begin? As this chapter demonstrates, the lines are not always easy to define and are still being debated today. Some people argue that southern states fought the Civil War to preserve the concept of states’ rights, but this argument is incorrect. Southern secessionists were not interested in states’ rights per se; what they wanted was to continue slavery without federal intervention. States’ rights was a convenient rationale for their proslavery position.

Modern political debates also use states’ rights as a cover for substantive policy disagreements. Some opposition to expanding protections for LGBTQIA+ individuals is justified using a states’ rights argument, that the federal government does not have the power to dictate “one size fits all” policy choices for communities throughout the nation. For example, some states require proof of sexual reassignment surgery before changing the name and gender on an individual’s birth certificate, while others have much looser requirements. If the federal government tried to impose uniform standards, some opponents would likely cite states’ rights as their justification. Of course, their opposition is not driven by a belief about the limits of federal power—rather, it is their opposition to changing the birth certificate regulations.

After the Civil War, constitutional amendments banned slavery (Thirteenth Amendment), prohibited states from denying citizens due process or the equal protection of the laws (Fourteenth Amendment), and gave newly freed men the right to vote (Fifteenth Amendment). Congress also passed the 1875 Civil Rights Act (although it was later overturned by the Supreme Court). The Fourteenth Amendment was the most important in terms of federalism because it was the constitutional basis for many of the civil rights laws passed by the federal government during Reconstruction. The Civil War fundamentally changed the way Americans thought about the relationship between the national government and the states: before the war people said “the United States are . . . ,” but after the war they said “the United States is . . .”

The Dred Scott decision, covered here in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, was the subject of much public interest when it was handed down in 1857. The decision inflamed tensions between states that allowed slavery and states that did not, and it vindicated those who saw state law as superior to federal law.

The Dred Scott decision, covered here in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, was the subject of much public interest when it was handed down in 1857. The decision inflamed tensions between states that allowed slavery and states that did not, and it vindicated those who saw state law as superior to federal law.

The Supreme Court and Limited National Government The assertion of power by Congress during Reconstruction was short-lived, as the Supreme Court soon stepped in again to limit the power of the national government. In 1873, the Court reinforced the notion of dual federalism, ruling that the Fourteenth Amendment did not change the balance of power between the national and state governments. Specifically, the Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment right to due process and equal treatment under the law applied to individuals’ rights only as citizens of the United States, not to their state citizenship.4 By extension, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and the other liberties protected in the Bill of Rights applied only to laws passed by Congress, not to state laws. Here again, these decisions can be read as an articulation of a theoretical interpretation of the Constitution, but they are also part of a broader, more concrete debate over how much the government should regulate interactions between individuals, or between individuals and corporations.

In 1883, the Court overturned the 1875 Civil Rights Act, which had guaranteed equal treatment in public accommodations. The Court argued that the Fourteenth Amendment did not give Congress the power to regulate private conduct, such as whether a White restaurant owner had to serve a Black customer; it affected only the conduct of state governments, not individuals in these states.5 This narrow view of the Fourteenth Amendment left the national government powerless to prevent southern states from implementing state and local laws that led to complete segregation of Black Americans and White Americans in the South (called Jim Crow laws) and the denial of many basic rights to Black Americans after northern troops left the South at the end of Reconstruction.

After the Supreme Court struck down the 1875 Civil Rights Act, southern states were free to impose Jim Crow laws. These state and local laws led to complete racial segregation, even for public waiting rooms.

After the Supreme Court struck down the 1875 Civil Rights Act, southern states were free to impose Jim Crow laws. These state and local laws led to complete racial segregation, even for public waiting rooms.

The Supreme Court also limited the reach of the national government by curtailing Congress’s authority to regulate the economy through its commerce clause powers. In a series of cases in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Supreme Court endorsed a view of laissez-faire—French for “leave alone”—capitalism aimed at protecting business from regulation by the national government. To this end, the Court defined clear boundaries between interstate and intrastate commerce, ruling that Congress could not regulate any economic activity that occurred within a state (intrastate). The Supreme Court let some national legislation that was connected to interstate commerce stand, such as the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890), which placed limits on monopolies. However, when the national government tried to use this act to break up a cartel of four sugar companies that controlled 98 percent of the nation’s sugar production, the Court ruled that Congress did not have this power. The Court’s decision argued that the commerce clause allowed Congress to regulate the transportation of goods, not their manufacture, and the sugar in question was made within a single state. Even if the sugar was sold throughout the country, this was “incidental” to its manufacture.6 On the same grounds, the Court struck down attempts by Congress to regulate child labor.7

Cooperative federalism

From the early years of the twentieth century through the 1930s, a new era of American federalism emerged in which the national government became much more involved in activities that were formerly reserved for the states, such as transportation, civil rights, agriculture, social welfare, and management–labor relations. At first, the Supreme Court resisted this broader reach of national power, clinging to its nineteenth-century conception of dual federalism.8 But as commerce became more national, the distinctions between interstate and intrastate commerce, and between manufacture and transportation, became increasingly difficult to sustain. Starting in 1937 with the landmark ruling National Labor Relations Board v. Jones and Laughlin Steel Corporation, the Supreme Court largely discarded these distinctions and gave Congress far more latitude to shape economic and social policy for the nation.9

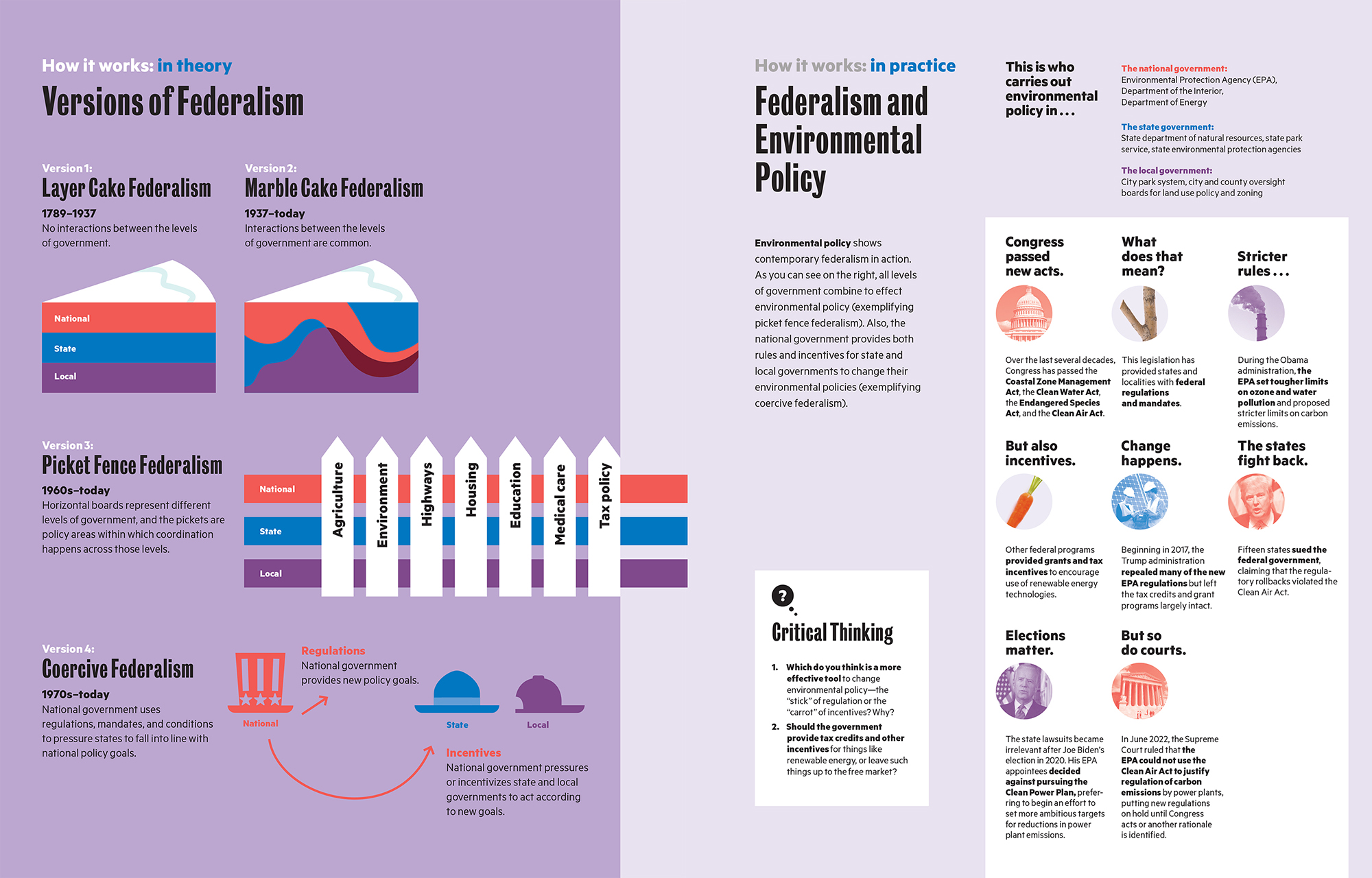

Shifting National–State Relations The type of federalism that emerged in this era is called cooperative federalism, or “marble cake” federalism, as opposed to the “layer cake” model of dual federalism.10 As the image of a marble cake suggests, the boundaries of state and national responsibilities are less well defined than they are under dual federalism. With the increasing industrialization and urbanization of the late 1930s and 1940s, along with the Great Depression, more complex problems arose that could not be solved at one level of government. Cooperative federalism adopted a more practical focus on intergovernmental relations and the efficient delivery of services. State and local governments maintained a level of influence as the implementers of national programs, but the national government played an enhanced role as the initiator, director, and funder of key policies.

“Cooperative federalism” accurately describes this important shift in national–state relations in the first half of the twentieth century, but it only partially captures the complexity of modern federalism. The marble cake metaphor falls short in one important way: the lines of authority and patterns of cooperation are not as messy as implied by the gooey flow of chocolate through white cake. Instead, the 1960s metaphor of picket fence federalism is a better description of cooperative federalism in action. As the How It Works graphic on pages 92–93 shows, each picket of the fence represents a different policy area, and the horizontal boards that hold the pickets together represent the different levels of government. This is a much more orderly image than the marble cake provides, and it illustrates important implications about how policy is made across levels of government.

The most important point to be drawn from this analogy is that activity in the cooperative federal system occurs within pickets of the fence—that is, within policy areas. Policy makers within a given policy area will have more in common with others in that area (even if they are at different levels of government) than they do with people who work in different areas (even if they are at the same level of government). For example, someone working in a state’s Department of Natural Resources will have more contact with people working in local park programs and the national Department of the Interior than with people who also work at the state level but who focus on, say, public health.

Cooperative federalism, then, is likely to emerge within policy areas rather than across them. This may create problems for the chief executives who are trying to run the show (mayors, governors, the president), as rivalries develop among policy agencies competing for funds. Also, contact within policy areas is not always cooperative. (Think of detective shows in which the FBI arrives to investigate a local crime and pulls rank on the town sheriff, provoking resentment from local law-enforcement officials.) This is the inefficient side of picket fence federalism in action.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal shifted more power than ever to the national government. Through major new programs to address the Great Depression, such as the Works Progress Administration construction projects pictured here, the federal government expanded its reach into areas that had been primarily the responsibility of state and local governments.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal shifted more power than ever to the national government. Through major new programs to address the Great Depression, such as the Works Progress Administration construction projects pictured here, the federal government expanded its reach into areas that had been primarily the responsibility of state and local governments.

“Why Should I Care?”

Why is it important to understand the history of federalism? You might think that the Civil War ended the debates over nation-centered versus state-centered federalism (in favor of the national government), but disputes today over immigration, health care, welfare, and education policy all revolve around the balance of power between the levels of government. State legislatures that talk about ignoring federal criticisms of their policy choices are invoking the same arguments used by advocates of states’ rights in the 1830s and 1840s concerning tariffs and slavery.

Glossary

- dual federalism

- The form of federalism favored by Chief Justice Roger Taney, in which national and state governments are seen as distinct entities providing separate services. This model limits the power of the national government.

- states’ rights

- The idea that states are entitled to a certain amount of self-government, free of federal government intervention. This became a central issue in the period leading up to the Civil War.

- cooperative federalism

- A form of federalism in which national and state governments work together to provide services efficiently. This form emerged in the late 1930s, representing a profound shift toward less concrete boundaries of responsibility in national–state relations.

- picket fence federalism

- A more refined and realistic form of cooperative federalism in which policy makers within a particular policy area work together across the levels of government.

Endnotes

- Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873). See Ronald M. Labbe and Jonathan Lurie, The Slaughterhouse Cases: Regulation, Reconstruction, and the Fourteenth Amendment (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003). Return to reference 4

- Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883). Return to reference 5

- United States v. E. C. Knight Co., 156 U.S. 1 (1895). Return to reference 6

- Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 U.S. 251 (1918). Return to reference 7

- Schechter Poultry Corporation v. United States, 295 U.S. 495 (1935). Return to reference 8

- Four key cases are West Coast Hotel Company v. Parrish (1937), Wright v. Vinton Branch (1937), Virginia Railway Company v. System Federation (1937), and National Labor Relations Board v. Jones and Laughlin Steel Corporation (1937). Return to reference 9

- Martin Grodzins, The American System (New York: Rand McNally, 1966). Return to reference 10