Astronomers Find Massive Black Hole in the Early Universe

Brooks Hays

Even though you may not yet know much about black holes, you can begin to make sense of some of the numbers astronomers use to talk about them.

June 25 (UPI)—With the help of a trio of Hawai’ian telescopes, astronomers have imaged the 13-billion-year-old light of a distant quasar—the second-most distant quasar ever found.

Scientists gave the new quasar an indigenous Hawaiian name, Pōniuā‘ena, which means “unseen spinning source of creation, surrounded with brilliance.” Researchers described the brilliant object in a new paper, which is available in preprint format online and will soon be published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Quasars are like lighthouses, their beams hailing from far away in the ancient universe. Powered by supermassive black holes at the center of galaxies, quasars are some of the brightest objects in the universe.

As astronomers peer deeper into the cosmos, they’re able to see what the universe was like during its earliest days. In this instance, the Pōniuā‘ena’s lighthouse-like beacon hails from a period when the universe was still in its infancy—just 700 million years after the Big Bang.

The light of J1342+0928, a quasar spotted in 2018, is older and more distant, but the power and size of Pōniuā‘ena is unmatched in the early universe. Spectroscopic observations of Pōniuā‘ena, recorded by the Keck and Gemini observatories, revealed a supermassive black hole with a mass 1.5 billion times that of the sun.

“Pōniuā‘ena is the most distant object known in the universe hosting a black hole exceeding one billion solar masses,” lead study author Jinyi Yang, postdoctoral research associate at the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory, said in a news release.

According to Yang and colleagues, for a black hole to grow to such a tremendous size so early in the history of the universe, it would have needed to start out as a 10,000-solar-mass “seed” black hole, born no later than 100 million years after the Big Bang.

“How can the universe produce such a massive black hole so early in its history?” said Xiaohui Fan, associate head of the astronomy department at the University of Arizona. “This discovery presents the biggest challenge yet for the theory of black hole formation and growth in the early universe.”

The light of distant objects, including quasars and massive galaxies in the early universe, can help scientists pinpoint the reionization of the universe. Astrophysicists estimate reionization occurred between 300 million years and one billion years after the Big Bang, but astronomers haven’t been able to determine exactly when and how quickly it happened.

The phenomenon describes the ionization of hydrogen gas as the first stars, quasars, galaxies, and black holes came into existence. Prior to the reionization, the universe was without distinct light sources. Diffuse light dominated, and most radiation was absorbed by neutral hydrogen gas.

“Pōniuā‘ena acts like a cosmic lighthouse,” said study coauthor Joseph Hennawi, a cosmologist and an associate professor in the department of physics at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “As its light travels the long journey towards Earth, its spectrum is altered by diffuse gas in the intergalactic medium which allowed us to pinpoint when the Epoch of Reionization occurred.”

Pōniuā‘ena was initially spotted by a deep universe survey using the observations of the University of Hawai’i Institute for Astronomy’s Pan-STARRS1 telescope on the Island of Maui. Later, scientists used the Gemini Observatory’s GNIRS instrument, as well as the Keck Observatory’s Near Infrared Echellette Spectrograph, to confirm the identify of Pōniuā‘ena.

“The preliminary data from Gemini suggested this was likely to be an important discovery,” said study coauthor Aaron Barth, a professor in the physics and astronomy department at the University of California, Irvine. “Our team had observing time scheduled at Keck just a few weeks later, perfectly timed to observe the new quasar using Keck’s NIRES spectrograph in order to confirm its extremely high redshift and measure the mass of its black hole.”

- The article describes the light from this object as being 13 billion years old. Is this object inside or outside of the Milky Way Galaxy?

- Which panel of Figure 1.3 would be most useful for showing someone else how far away this object is?

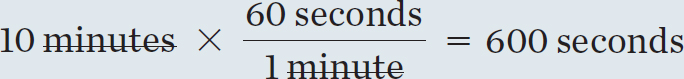

- This supermassive black hole has a mass of 1.5 billion times that of the Sun. Write this number in scientific notation.

- This black hole must have been born from a “seed” that formed no later than 100 million years after the Big Bang. In an astronomical context, is that “soon” after the Big Bang, or a “long time” after the Big Bang? How do you know?

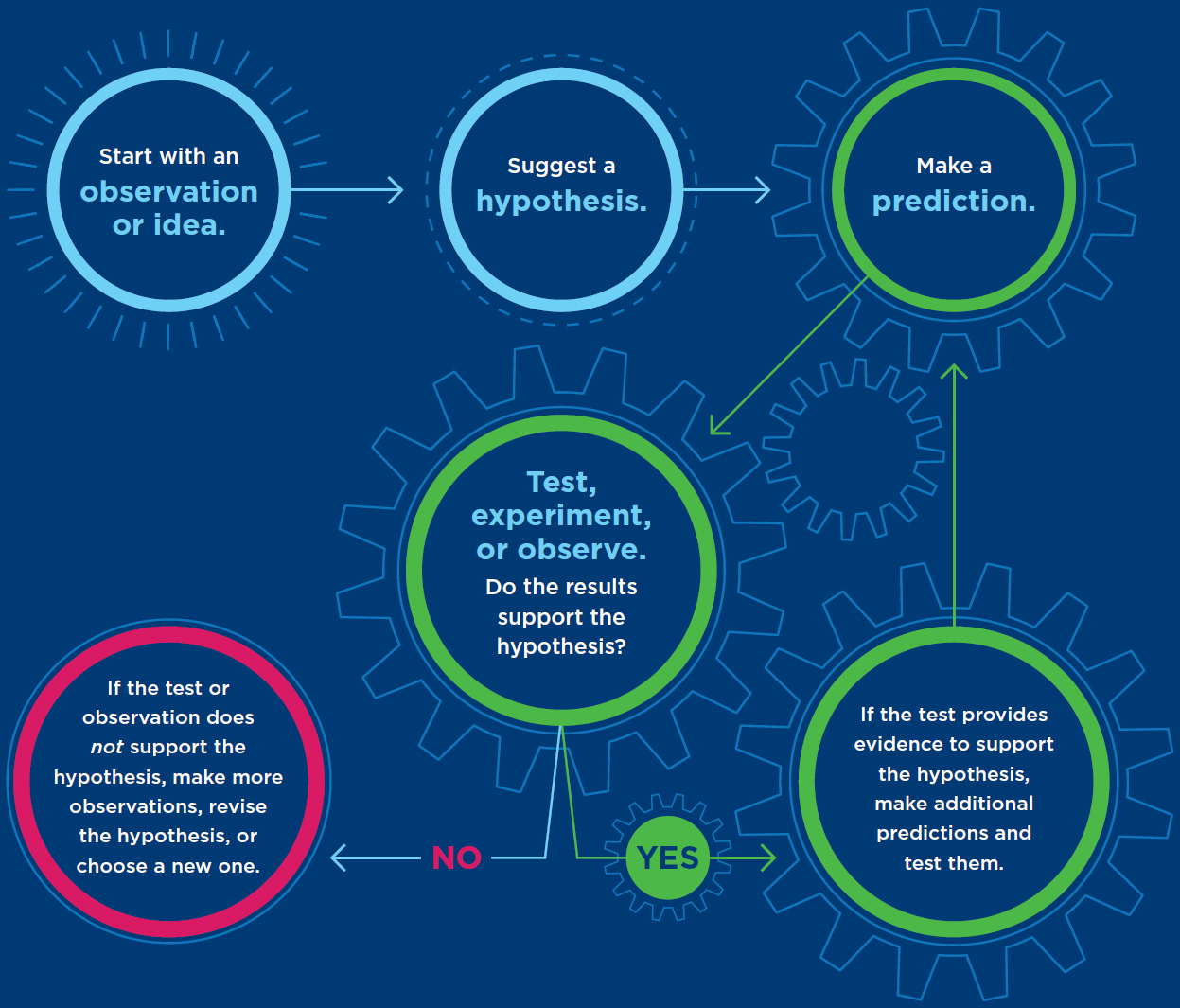

- What is the new question that Xiaohui Fan is asking, now that this observation has been made? Where do questions like this fit into the scientific method shown in the Process of Science Figure and discussed in Section 1.2?

Source: https://www.upi.com/Science_News/2020/06/25/Astronomers-find-massive-black-hole-in-the-early-universe/7781593108062/.

Answer

Answer