SEX-LINKED TRAITS

So far, we have focused on traits and genes located on the autosomes, but the sex chromosomes also carry important genetic material. Traits that are determined by genes on the sex chromosomes are called sex-linked traits, and they have unusual patterns of inheritance and physical expression. As noted in Lab 2, the X and Y chromosomes have key differences in the genes they each carry. The Y chromosome has a limited number of genes, and they are largely tied to traits related to maleness. The X chromosome has many more genes that are important for both males and females. In XX females, two copies of the X chromosome (and any associated genes) are present, so X-linked traits follow the same patterns described for Mendelian traits in general. In XY males, however, only one copy of the X chromosome (and its genes) is present, which may cause unusual patterns of phenotypic expression.

In most Mendelian traits, an individual has two copies of the gene, allowing for the homozygous and heterozygous genotypes previously discussed. However, an XY male who has an unusual X-linked trait on his X chromosome will have no alternative allele on a second X chromosome to compensate for it. Therefore, whatever allele appears at the genetic level on the X chromosome will appear on the phenotypic level in the individual’s body. In contrast, an XX female with an unusual allele on one X has another allele on her other X to make up for it. The unusual trait variant is less likely to be expressed in her than in an XY male with the same allele.

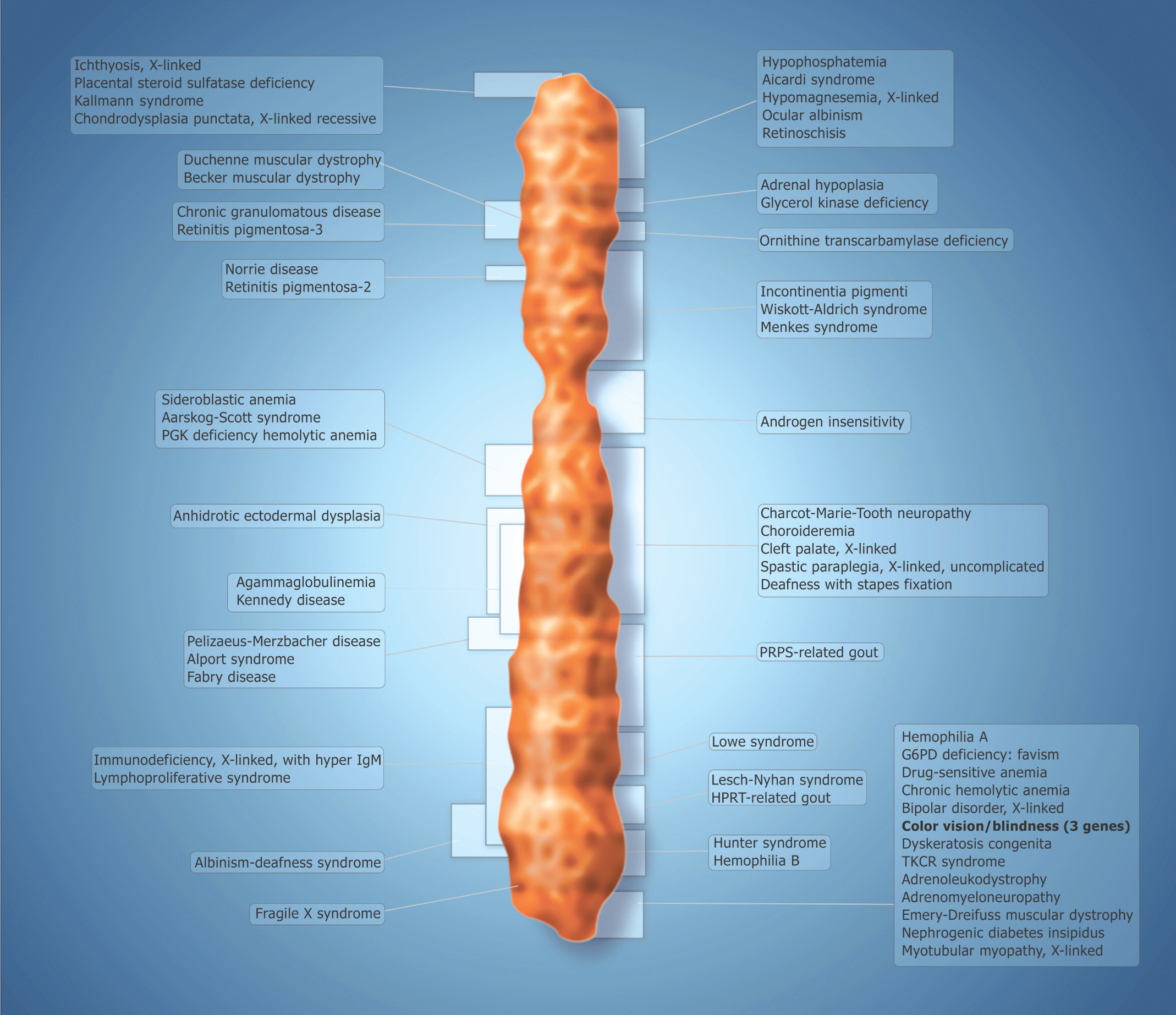

The X chromosome has genes for many traits that are not found on the Y chromosome. These X-linked traits are more likely to be expressed in XY males, but both males and females may have and pass on these genes to their offspring.

Figure Credit: Monica Schroeder/Science Source

The X chromosome has many genes, so numerous traits are X-linked (Figure 3.5). A classic example is color vision. Humans, like many of our close primate relatives, have tricolor vision that is determined by three separate genes on the X chromosome. If an XY male has an alternative form of one of these genes, it may affect his ability to perceive certain colors, resulting in a condition known as color blindness. It is estimated that approximately 5%–8% of males worldwide have the most common form of color blindness (red-green color blindness). A male that has a color blindness allele may then pass it on to his female offspring who inherit his X chromosome. However, his male offspring inherit his Y chromosome, so he cannot pass the allele to them.

The expression and inheritance of the trait in females is a bit different. If an XX female has an alternative form of one of the color vision genes, she may still have full color vision because her other X carries a normal version of the gene that makes up for it. Such individuals are called “carriers” for the trait. They carry the allele and may pass it on should that X chromosome be inherited by offspring, but they do not express the trait themselves. They may not even know they carry the allele at all. It is possible for XX females to be color blind, but it is very rare, because they would need the same unusual allele on both of their X chromosomes to manifest color blindness at the phenotypic level. For this reason, X-linked traits are more likely to be expressed in males, but both males and females may have alleles for those traits and may pass them on to their offspring.

EXPLORING FURTHER

EXPLORING FURTHER

The ABO Blood Group System We have focused on Mendelian traits, such as plant height in pea plants, with one dominant allele and one recessive allele. However, Mendelian traits often have more complex dominance relationships between the alleles involved. The classic example in humans is the ABO blood group system.

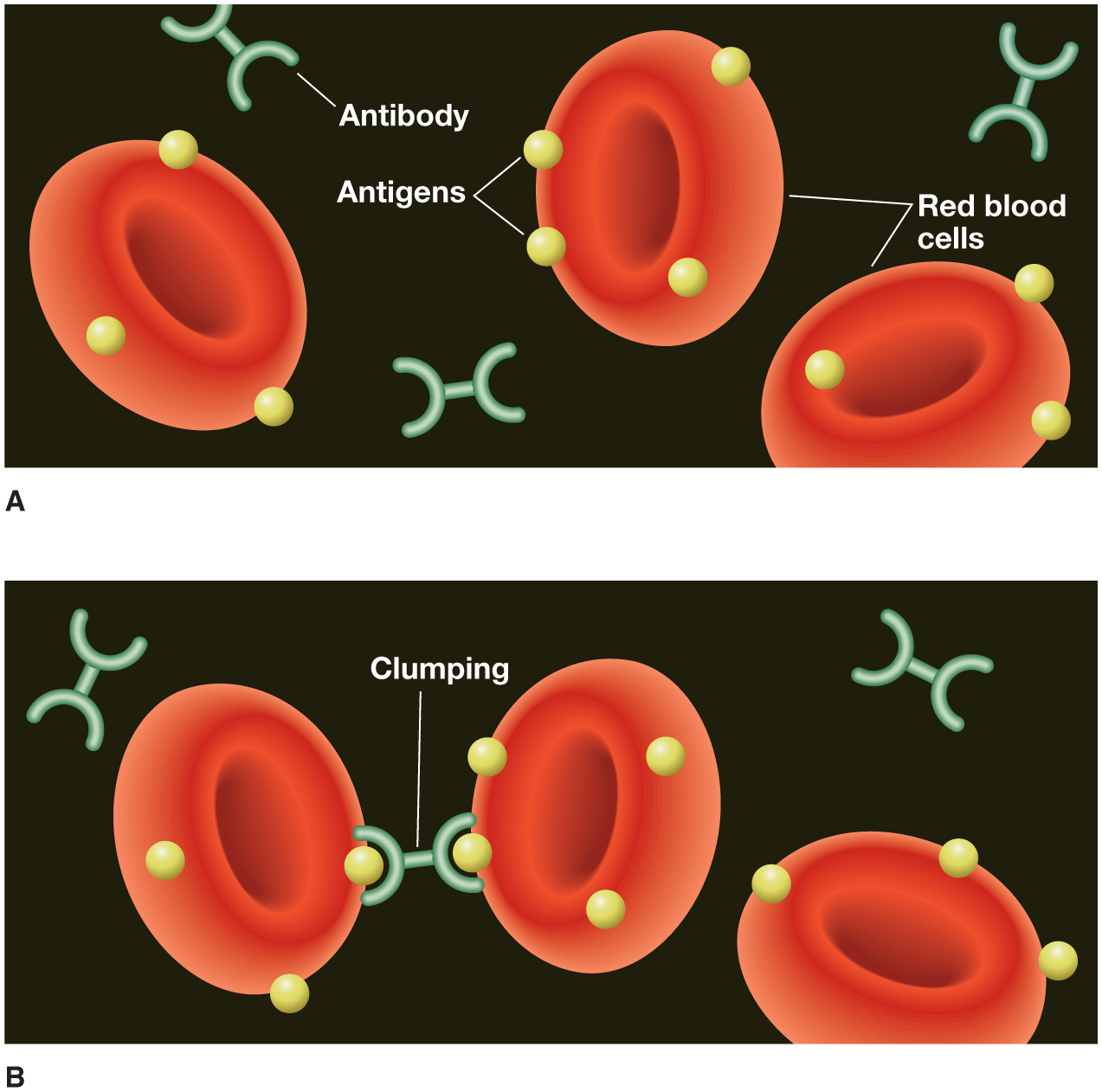

Different types of cell surface markers, called antigens, are found on the surfaces of our red blood cells. In general, an antigen is any substance (such as a bacterium or enzyme, or fragments thereof) that triggers an immune response. Blood group antigens are either sugars or proteins. The antigens expressed on a red blood cell determine an individual’s blood type. The main two blood groups are called ABO (with blood types A, B, AB, and O) and Rh (with Rh-positive and Rh-negative blood types). In the ABO blood group system there are two antigens: antigen A and antigen B (FIGURE 3.6A). We know that the A and B blood antigens are sugars, but not much is known about their function in the body today or in our evolutionary past.

The alleles for these antigens are found at one genetic locus, which means that ABO blood type is a Mendelian trait. A person can inherit the A antigen allele, the B antigen allele, or the O allele (which is expressed as having neither antigen on the blood cell surface).

These alleles make six genotypes for the ABO blood system possible:

- A person can be AA, with the A antigen allele inherited from both parents.

- A person can be AO, with the A antigen allele inherited from one parent and the O allele inherited from the other parent.

- A person can be BB, with the B antigen allele inherited from both parents.

- A person can be BO, with the B antigen allele inherited from one parent and the O allele inherited from the other parent.

- A person can be AB, with the A antigen allele inherited from one parent and the B antigen allele inherited from the other parent.

- A person can be OO, with the O allele inherited from both parents.

Interestingly, there are only four corresponding phenotypes or blood types:

- People with the AA genotype and the AO genotype have A antigens on their red blood cells, giving them blood type A as their phenotype.

- People with the BB and BO genotypes have B antigens on their red blood cells, giving them blood type B as their phenotype.

- People with the AB genotype have both A antigens and B antigens on their red blood cells, giving them blood type AB as their phenotype.

- People with the OO genotype do not have either type of antigen on their red blood cells, giving them blood type O as their phenotype.

This discrepancy in the number of possible genotypes and phenotypes suggests that the ABO blood group system has a complex pattern of dominance and recessiveness. The A antigen allele is dominant over the O allele. The O allele does not result in antigens, but the presence of the A allele in a heterozygous individual results in the production of the A antigens, giving AO individuals the A blood phenotype. The B antigen allele is also dominant over the O allele, with BO individuals having the B blood phenotype. The only individuals with a true O blood type are homozygous for the O allele, further suggesting that the O allele is recessive. The relationship between the A antigen allele and B antigen allele is particularly interesting. These two alleles are what we call codominant. When the two alleles appear together, as in AB individuals, both alleles are expressed in the phenotype. One is not dominant over the other; they are equally dominant. Therefore, when documenting genotypes in codominant traits like human ABO blood type, letters for both alleles are used (A and B), rather than the same letter in uppercase and lowercase (A and a).

(A) The A and B blood antigens are found on the surfaces of red blood cells. When foreign blood antigens are introduced into the body via the transfusion of incompatible blood, antibodies are produced. (B) The antibodies attach to the antigens and cause the blood cells to clump, which can restrict blood flow.

While much of the function of these red blood cell antigens is still unknown, we do know that exposure to foreign blood antigens triggers a dangerous response from the immune system that can be fatal. The body differentiates between its normal antigens (self-antigens) and foreign antigens. Many foreign antigens, such as bacteria, trigger a protective reaction from the immune system. The body produces antibodies, which are special proteins that attack the antigens directly or mark them for attack by other parts of the immune system. This process allows the body to neutralize and fight off infections. In the case of the blood cell surface antigens, the body identifies any foreign blood antigens and produces antibodies to combat them (FIGURE 3.6B). The antibodies attach to the antigens and cause the blood cells to clump together. The coagulated blood does not travel smoothly through the blood vessels, and the body cannot get the blood and oxygen it needs. This condition can result in death.

Because of the antibody response to foreign blood antigens, it is essential that we know an individual’s blood genotype and phenotype to choose compatible blood for transfusions. Individuals who have blood type A can receive blood from people who also have blood type A because their antigens are the same. Individuals who have blood type B can receive blood from people who also have blood type B because their antigens are the same. However, a person with blood type A cannot receive blood from a person with blood type B (and vice versa) because it introduces foreign blood antigens that will trigger an immune response.

A person who has blood type O can receive blood only from someone who also has blood type O. Someone with blood type O doesn’t have either type of antigen, so both the A and the B antigens will be considered foreign and will trigger an immune response. However, blood type O is considered to be the universal donor blood. It doesn’t have either antigen, so it will not introduce a foreign antigen to the body of a recipient. Anyone can receive blood from a person with blood type O.

People who have blood type AB can receive blood from anyone, making them universal recipients. A person with blood type AB can receive blood from someone else who also has blood type AB, but can also receive blood from someone who has blood type A or someone who has blood type B. Because the A antigen allele and the B antigen allele are codominant, people with blood type AB have both types of antigens in their bodies. When type A blood is introduced, it is accepted, because the A antigen is already present. The same is true for the introduction of type B blood. The introduction of type O blood is also successful because it does not have any antigens that cause clumping.

The complex relationships of dominance and recessiveness among these different antigen alleles create a complicated picture of blood group genotypes and phenotypes, and these genotypes and phenotypes must be understood in order to successfully transfuse blood. Because transfusion reactions can also be trigged by antibody responses to other blood components (such as Rh factor), blood donations are now carefully screened before they are given to recipients to reduce the risk of incompatibility complications. Transfusion patients are also closely monitored for signs of other reactions, such as allergic responses to donated blood, so they can be treated as needed. Interestingly, the ABO blood type alleles seem to have unusual distributions across populations worldwide. We will return to this observation in Lab 8 when we discuss human variation.

Glossary

- sex-linked trait

- a trait coded for by a gene on the X or Y chromosome (although typically used to refer to traits on the X chromosome)

- color blindness

- limited perception of certain colors, which may be the result of variation in the alleles for color vision

- antigen

- (in ABO blood group system) the cell surface marker found on red blood cells that relates to an individual’s ABO blood type and triggers antibody reactions to a foreign blood antigen

- codominant

- circumstance where multiple alleles are expressed in the phenotype, without one being clearly dominant over the other

- antibody

- a protein that attacks antigens directly or marks them for attack by other parts of the immune system