NAWM 20aAnonymous, Motets on Tenor Dominus, Factum est salutare/Dominus

The Motet

A clausula, cut loose from its larger setting, could enjoy a second life as a separate piece, a little independent composition in melismatic polyphony. When Latin or French words were added to the upper voice, a new type of work, originating like earlier troped genres, was created: the motet (from the French mot, meaning “word”). The Latin form, motetus, also designates the second voice — the original duplum, now sporting its own text. In three- and four-part motets, the third and fourth voices carry the same names — triplum and quadruplum — that they had in organum.

The motet originated, then, when musicians at Notre Dame troped the repertory of clausulae preserved in the Magnus Liber. These clausulae, having earlier belonged to the genre of organum, themselves featured newly created melodies layered above old chants. Thus, a defining characteristic of the motet was its use of borrowed chant material in the tenor. Such a tenor was known as the cantus firmus (“plain chant”; pl. cantus firmi). Just as new clausulae were produced using the same favorite cantus firmi, so, too, were motets throughout France and western Europe during the thirteenth century derived from a common stock of motet melodies — both tenors and upper parts — and transformed into new works.

Some motets were intended for nonliturgical use, and their upper voices could have vernacular texts while the tenor may have been played on instruments or vocalized wordlessly. After 1250, it was customary to use different but topically related texts in as many as two upper voices. These motets are identified by a compound title made up of the incipit (the first word or words) of each voice part, beginning with the highest.

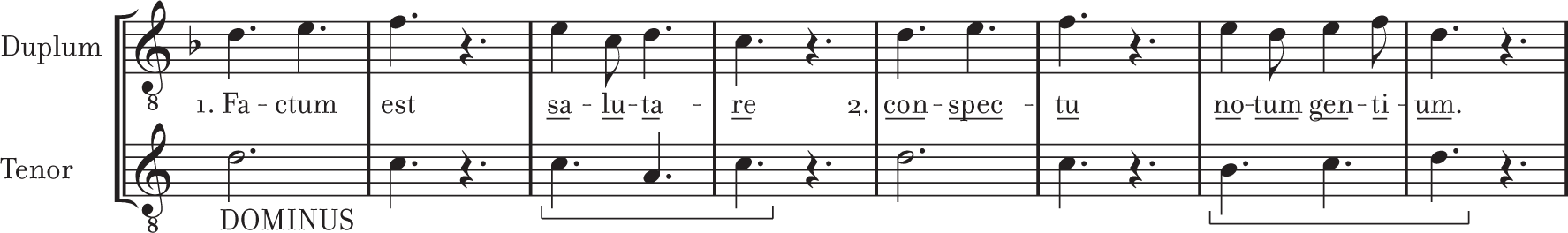

A typical early motet is Factum est salutare/Dominus (NAWM 20a), shown in Example 3.9 and based on one of the substitute clausulae from the Magnus liber (Example 3.7a). Like many early Latin motets based on clausulae, this text is a trope on the original chant text, elaborating its meaning and drawing on its words or sounds. The poem ends with the word “Dominus” (“Lord”), to which the tenor melody was originally sung, and incorporates several other words from the chant (underlined in the example), some of which are echoed in subsequent rhymes. The discant clausula, originally a musical decoration of a single word, is here further embellished by the addition of words, like a gloss upon a gloss. The resulting motet is an ingenious composite artwork with multiple layers of borrowing and meaning. In an ecclesiastical culture that treasured commentary, allegory, and new ways of reworking traditional themes, such pieces must have been highly esteemed for their many allusions.

Leoninus (fl. 1150–ca. 1201)

Perotinus (fl. 1200–1230)

More information

(British Library, London, UK/© British Library Board. All rights reserved./Bridgeman Images.)

Leoninus served at the cathedral of Paris in many capacities, beginning in the 1150s, before construction started on Notre Dame Cathedral. His title (Magister, or Master) suggests that he earned a Master of Arts degree, presumably at the University of Paris, and eventually became a priest and then canon at Notre Dame. As a poet, he wrote a paraphrase, in verse, of the first eight books of the Bible as well as several shorter works.

Less is known about Perotinus. He, too, possibly had a Master of Arts and must have held an important position at Notre Dame.

Virtually all we know about the musical activities of Leoninus and Perotinus is contained in an anonymous treatise from about 1275. The writer makes a pointed comparison between the two:

And note that Master Leoninus was an excellent organista [singer or composer of organum], so it is said, who made the great book of organum [magnus liber organi] on the gradual and antiphonary to enrich the Divine Service. It was in use up to the time of Perotinus the Great, who edited it and made many better clausulae or puncta, being an excellent discantor [singer or composer of discant], and better [at discant] than Leoninus was. (This, however, is not to be asserted regarding the subtlety of organum, etc.)Now, this same Master Perotinus made the best quadrupla [four-voice organa], such as Viderunt and Sederunt, with an abundance of musical colores [melodic formulas]; likewise, the noblest tripla [three-voice organa], such as Alleluia Posui adiutorium and [Alleluia] Nativitas, etc. He also made three-voice conductus, such as Salvatoris hodie, and two-voice conductus, such as Dum sigillum summi patris, and also, among many others, monophonic conductus, such as Beata viscera, etc. [Concerning the conductus, see p. 63.] The book or, rather, books of Master Perotinus were in use up to the time of Master Robertus de Sabilone in the choir of the Paris cathedral of the Blessed Virgin [Notre Dame], and from his time up to the present day.1

Like the Scholastic theologians who glossed and commented on the Scriptures, adding their own layers of interpretation to those of previous scholars. Leoninus and Perotinus expanded the musical dimensions of the liturgy by “glossing” the preexisting chant. Their newly added voices sung in counterpoint to the Gregorian melody were like the marginal commentaries surrounding a central authoritative text.

Example 3.9 Factum est salutare/Dominus

More information

Salvation was made known in the sight of the people.

Musicians soon regarded the motet as a genre independent of church performance. In the process, the tenor lost its connection as a melody to a specific place in the liturgy and became raw material for a new piece, a firm foundation for the upper voice or voices. This change in the role of motets raised new possibilities that encouraged musicians to rework existing motets in several ways: (1) writing a different text for the duplum, in Latin or French, that was no longer necessarily linked to the chant text and was often on a secular topic; (2) adding a third voice to those already present; and (3) giving the additional parts words of their own to create a double motet (one with two texts above the tenor). Motets were also devised from scratch, with one of the tenor melodies from the Notre Dame clausula repertory being laid out in a new rhythmic pattern and new voices being added above it.

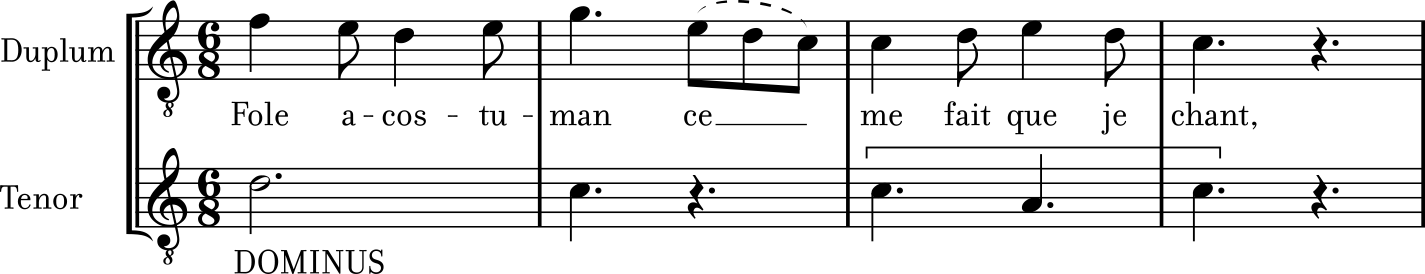

Example 3.10 Fole acostumance/Dominus

More information

Foolish custom makes me sing,

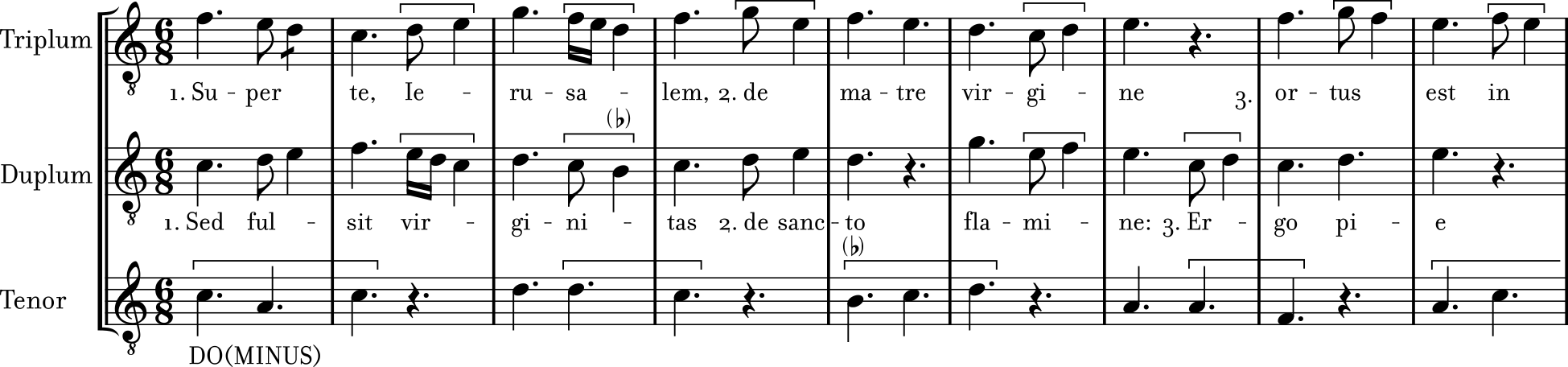

Example 3.11 Super te Ierusalem/Sed fulsit virginitas/Dominus

More information

Triplum: Over thee, Jerusalem, from the virgin mother has arisen in [Bethlehem]

Duplum: Rather, her virginity received its splendor from the Holy Spirit; therefore, pious [Lord]

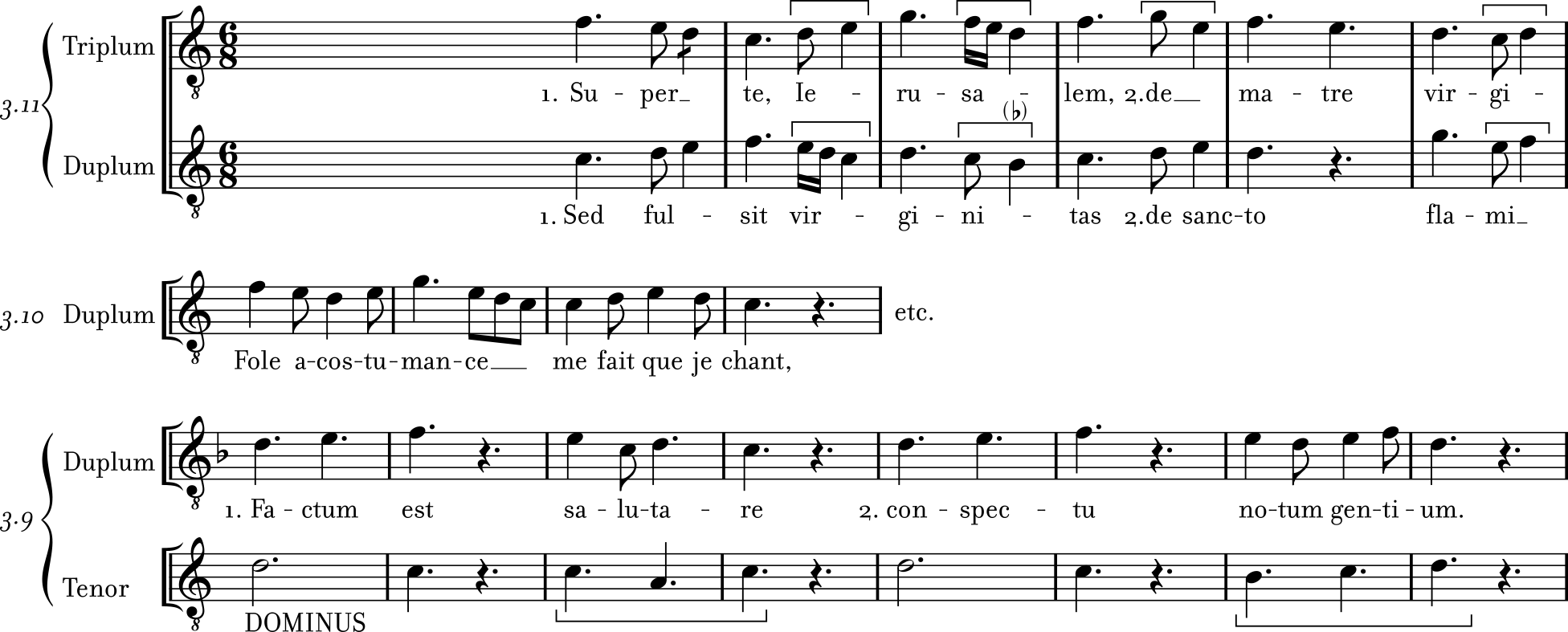

The two motets in Examples 3.10 and 3.11 illustrate some of these characteristics. Fole acostumance/Dominus (Example 3.10 and NAWM 20b) employs the same tenor as Example 3.9 but states it twice and substitutes a new, more quickly moving duplum for the original one. The doubled length and faster motion accommodate a much longer text, a secular French poem complaining that envy, hypocrisy, and deception have ruined France. The composer of Super te Ierusalem/Sed fulsit virginitas/Dominus (Example 3.11 and NAWM 20c) began with a portion of the same chant melisma on “Dominus” but imposed a different modal rhythmic pattern. The two upper voices set the first and second halves respectively of a Latin poem about the birth of Jesus, thereby confirming the motet’s connection to the feast of Christmas on which the tenor melody was originally sung and making it appropriate to be performed during that season, either in private devotions or as an addition to the church service. As in most motets with more than two voices, the upper parts rarely rest together or with the tenor, so that the music moves forward in an unbroken stream. A composite of Examples 3.9, 10, and 11, all on the same cantus firmus, may be seen in Example 3.12.

NAWM 20bAnonymous, Motets on Tenor Dominus, Fole acostumance/Dominus

NAWM 20c Anonymous, Motets on Tenor Dominus, Super te Ierusalem/Sed fulsit virginitas/Dominus

More information

(Bridgeman Images.)

In the earlier motets, all the upper parts were written in one melodic and rhythmic style. (Compare Figure 3.10.) Later composers distinguished the upper voices from each other as well as from the tenor, achieving more rhythmic freedom and variety both among and within voices. In this new kind of motet, called Franconian (after Franco of Cologne, a composer and theorist who was active from about 1250 to 1280), the triplum bears a longer text than the motetus and features a faster-moving melody with many short notes. The result is the kind of layered texture seen, for example, in the motet by Adam de la Halle (ca. 1240–1288?), De ma dame vient/Dieus, comment porroie/Omnes (NAWM 21; compare Figure 3.12). Here, rhythmic differences between the voices reinforce the contrast of texts, the triplum voicing the complaints of a man separated from his sweetheart and the duplum (motetus) the woman’s thoughts of him. Below them, the slowest-moving part, the tenor, repeats the melody for “omnes,” from the Gradual Viderunt omnes, twelve times.

NAWM 21 Adam de la Halle, De ma dame vient/Dieus, comment porroie/Omnes

Example 3.12 A composite of Examples 3.9, 3.10, and 3.11, all on the same tenor or cantus firmus, “Dominus”

More information

In Context The Motet as Gothic Cathedral

In Context The Motet as Gothic Cathedral

A distinctive feature of music is its movement through time. But to understand time, we must be able to measure it. The makers of polyphony in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries devised a way of measuring musical time so that it could be manipulated and controlled. By the late thirteenth century, the motet, wholly a creation of French musicians, illustrates this accomplishment better than any other genre of the era.

Each voice of a motet moves within its own rhythmic framework yet is perfectly compatible with every other voice. In the case of a three-voice motet, for example, the tenor measures the passage of time in long note values while the middle voice superimposes its own rhythmic design, consisting of shorter values, on the support created by the tenor. Meanwhile, the highest voice relates to time differently from its two partners, usually in notes that move even more quickly than those of the middle voice and with phrases that coincide with (or sometimes overlap) the ends of the phrases below. The result is a three-tiered structure in which each level is independent of, yet completely coordinated with, the other two levels.

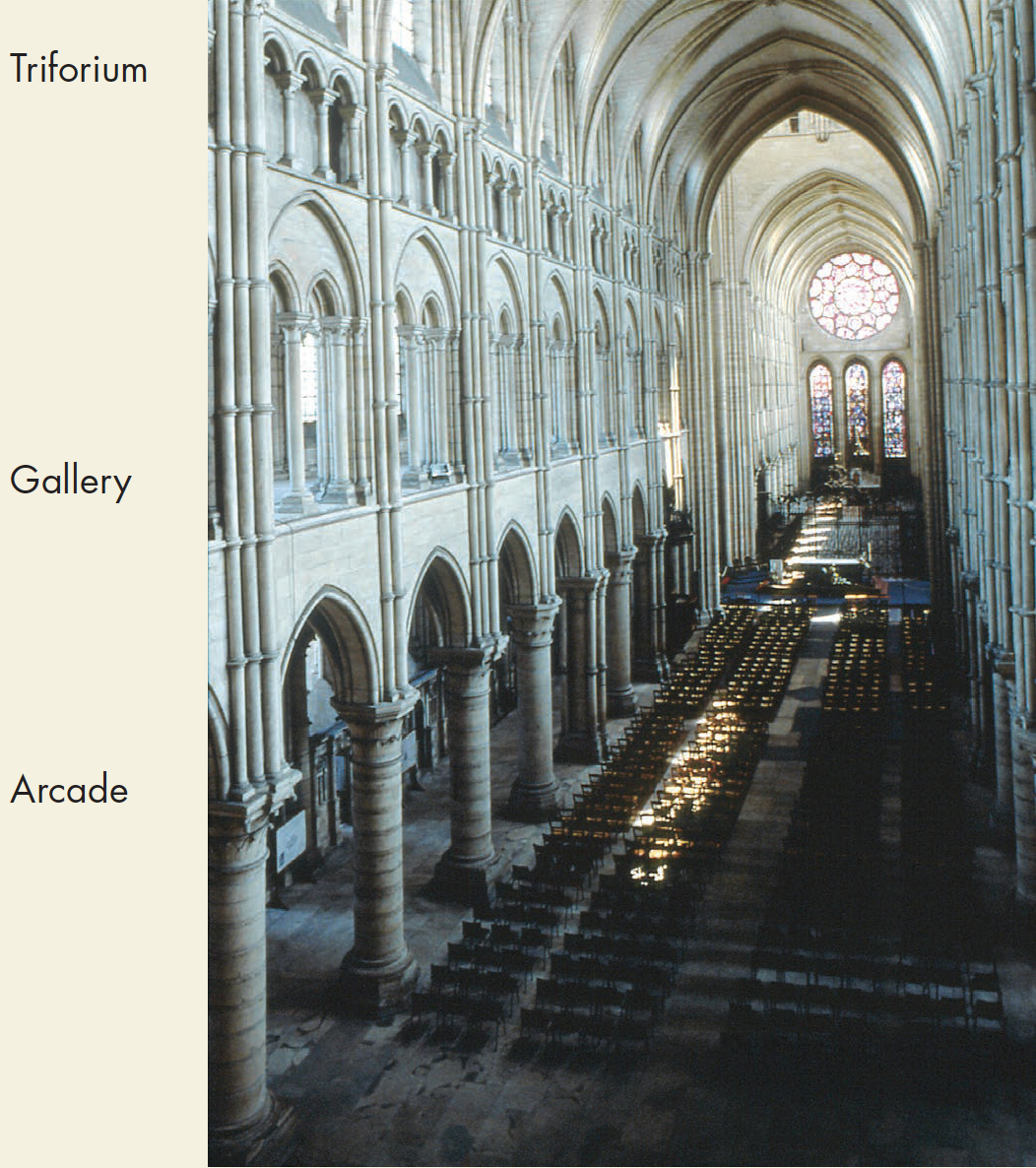

If we look at the interior space of a typical Gothic cathedral that was created by French architects during the very period in which the medieval motet flourished (see Figure 3.11), we see a formal design remarkably similar to the structure just described. Along either side of the nave, or central aisle of the church, is an arcade of huge columns that have been placed at regular intervals to define the length of the cathedral and support its soaring height. Along the next higher storey are the paired arches of the gallery, measuring the same regular spaces by smaller distances, in effect quickening the rhythm. Superimposed atop this layer, just below the level at which walls give way to windows, is a third tier of still smaller, triple arches (the triforium), ornamental rather than functional, independent of and yet perfectly harmonized with the lower levels.

More information

(Anthony Scibilia/Art Resource, NY.)

The similarities described here are not accidental: the architects of the Gothic style codified their principles of design from the same mathematical laws that the creators of modal rhythm and the composers of motets used in establishing their theories of proportion and measure. The results of their efforts are, on the one hand, a glorious edifice in which we can “hear” a kind of silent music and, on the other, a genre of polyphonic composition that allows us to “see” the harmonious plan of its underlying structure.

Neo-Gothic churches are still being built in our day. The chapel at West Point; Princeton University Chapel; Saint Thomas Church, Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, and the huge cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City; the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C.; Saint Paul’s Anglican Church in Toronto; Montreal’s Notre-Dame Basilica; and more than a hundred other North American churches all testify to the inspiring grandeur of the Gothic style.

The motet in France had an astonishing career in its first century. What began as a work of poetry more than a composition, fitting a new text to an existing piece of music, developed into the leading polyphonic genre, home to the most complex interplay of simultaneous and independent lines yet conceived. In their texts and structure, motets of the late thirteenth century mirrored both the century’s intellectual delight in complication and its architectural triumph of the Gothic cathedral (see In Context, p. 62).

Notes

- Translation adapted from Edward H. Roesner, “Who ‘Made’ the Magnus liber?” Early Music History 20 (2001): 227–28.Return to reference 1