What Is Anthropology?

Define anthropology and its unique approach to studying people.

Anthropology is the study of the full scope of human diversity, past and present, and the application of that knowledge to help people of different backgrounds better understand one another. Anthropologists investigate both our human origins and how we live together in groups today. The study of the vast diversity of human cultures across geographic space and time allows us to glimpse the broad potential for human belief and behavior that stretches beyond what we may have imagined in our own cultural context.

BRIEF BACKGROUND

The roots of anthropology lie in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when Europeans’ economic and colonial expansion increased that continent’s contact with people worldwide. The era’s technological breakthroughs in transportation and communication—shipbuilding, the steam engine, railroads, the telegraph—rapidly transformed the long-distance movement of people, goods, and information in terms of both speed and quantity. As colonization, communication, trade, and travel expanded, groups of merchants, missionaries, and government officials traveled the world and returned to Europe with reports and artifacts of what seemed to them to be “exotic” people and practices. More than ever before, Europeans encountered the incredible diversity of human cultures and appearances. Who are these people? they asked themselves. Where did they come from? Why do they appear so different from us?

Since the field’s inception in the mid-1800s, anthropologists have conducted research to answer specific questions confronting humanity. And they have applied their knowledge and insights to practical problems facing the world.

Franz Boas (1858–1942), one of the founders of American anthropology, became deeply involved in early twentieth-century debates on immigration, even serving for a term on a presidential commission examining U.S. immigration policies. In an era when many scholars and government officials considered the different people of Europe to be of biologically distinct races, U.S. immigration policies privileged immigrants from northern and western Europe over those from southern and eastern Europe. Boas worked to undermine these racialized views of immigrants. He conducted studies that showed the wide variation of physical forms within groups of the same national origin as well as the marked physical changes in the children and grandchildren of immigrants as they adapted to the environmental conditions in their new country (Baker 2004; Boas 1912).

Audrey Richards (1899–1984), who studied the Bemba people in the 1930s in what is now Zambia, focused on issues of health and nutrition among women and children, bringing food to the forefront of anthropology. Her ethnography Chisungu (1956) featured a rigorous and detailed study of the coming-of-age rituals of young Bemba women and established new standards for the conduct of anthropological research. Richards’s research is often credited with opening a pathway for the study of women’s and children’s health as well as food and nutrition in anthropology.

Today’s anthropologists, like Boas and Richards before them, apply their knowledge and research strategies to a wide range of social issues. More than half of anthropologists today work in applied anthropology—that is, they work outside of academic settings to apply anthropological strategies and insights directly to current world problems (American Anthropological Association 2019). Even many of us who work full time in a college or university are deeply involved in public applied anthropology.

For example, anthropologists study immigrants crossing the U.S.–Mexico border; street food vendors in Mumbai, India; climate change in the South Pacific islands; HIV/AIDS prevention programs in South Africa; financial firms on Wall Street; and Muslim judicial courts in Egypt. Anthropologists trace the spread of disease, promote economic development, conduct market research, and lead diversity training programs in schools, corporations, and community organizations. Anthropologists also study our human origins, excavating and analyzing the bones, artifacts, and DNA of our ancestors from millions of years ago to gain an understanding of where we’ve come from and what has made us who we are today.

ANTHROPOLOGY’S UNIQUE APPROACH

Anthropology today retains its core commitment to understanding the richness of human diversity. As we will explore throughout this book, the anthropologist’s toolkit of research strategies and analytical concepts enables us to appreciate, understand, and engage the diversity of human cultures in an increasingly global age and, in the process, to understand our own lives in a more complete way.

More information

A woman lying down receives a spa facial treatment from another woman dressed in white. She is applying a mask to her face with a paintbrush and another tool.

The Nacirema. In his now-famous article “Body Ritual among the Nacirema” (1956), anthropologist Horace Miner helps readers understand the tension between familiar and strange that anthropologists face when studying other cultures. Miner’s article examines the cultural beliefs and practices of a group in North America that has developed elaborate and unique practices focusing on care of the human body. He labels this group the “Nacirema.”

Miner hypothesizes that underlying the extensive rituals he has documented lies a belief that the human body is essentially ugly, is constantly endangered by forces of disease and decay, and must be treated with great care. Thus, the Nacirema have established intricate daily rituals and ceremonies, rigorously taught to their children, to avoid these dangers. For example, Miner describes the typical household shrine—the primary venue for Nacirema body rituals:

While each family has at least one shrine, the rituals associated with it are not family ceremonies but are private and secret. . . . The focal point of the shrine is a box or chest which is built into the wall. In this chest are kept the many charms and magical potions without which no native believes he could live. . . . Beneath the charm-box is a small font. Each day every member of the family, in succession, enters the shrine room, bows his head before the charm-box, mingles different sorts of holy water in the font, and proceeds with a brief rite of ablution. (Miner 1956, 503–4)

In addition, the Nacirema regularly visit medicine men and “holy-mouth men.” These individuals are specialists who provide ritual advice and magical potions.

The Nacirema have an almost pathological horror of and fascination with the mouth, the condition of which is believed to have a supernatural influence on all social relationships. Were it not for the rituals of the mouth, they believe that their teeth would fall out, their gums bleed, their jaws shrink, their friends desert them, and their lovers reject them. The daily body ritual performed by everyone includes a mouth-rite. It was reported to me that the ritual consists of inserting a small bundle of hog hairs into the mouth, along with certain magical powders, and then moving the bundle in a highly formalized series of gestures. (504)

Do these exotic rituals of a seemingly distant tribe sound completely strange to you, or are they vaguely familiar? Miner’s descriptions of the Nacirema are intended to make the strange seem familiar and the familiar strange. “Nacirema” is actually “American” spelled backward. Miner’s passages describe the typical American bathroom and personal hygiene habits: “Holy water” pours into the sink. The “charm-box” is a medicine cabinet. The Nacirema medicine men are doctors, and the “holy-mouth men” are dentists. The “mouth-rite” is toothbrushing.

Developing an anthropological perspective as we investigate the beliefs and practices of other cultures enables us to perceive our own cultural activities in a new light. Even the most familiar aspects of our lives may appear exotic, bizarre, or strange when viewed through the lens of anthropology. Through this cross-cultural training, anthropology unlocks our ability to imagine, see, and analyze the incredible diversity of human cultures. It also enables us to avoid the tendencies of ethnocentrism—that is, the impulse to use our own cultural norms to judge the cultural beliefs and practices of others.

To that end, anthropology has built upon the key concerns of early generations to develop a set of characteristics unique among the social sciences.

Anthropology Is Global in Scope. Our work covers the whole world and is not constrained by geographic boundaries. Anthropology was once distinguished by the study of faraway, seemingly exotic villages in developing countries. But from the beginning, anthropologists have been studying not only in the islands of the South Pacific, in the rural villages of Africa, and among Indigenous peoples in Australia and North America, but also among factory workers in Britain and France, among immigrants in New York, and in other groups in the industrializing world. Over the last forty years, anthropology has turned significant attention to urban communities in industrialized nations. With the increase of studies based in North America and Europe, it is fair to say that anthropologists now embrace the full scope of humanity—across geography and through time.

Anthropologists Start with People and Their Local Communities. Although the whole world is our field, anthropologists are committed to understanding the local, everyday lives of the people we study. Our unique perspective focuses on the details and patterns of human life in the local community and then examines how particular cultures connect with the rest of humanity. Sociologists, economists, and political scientists primarily analyze broad trends, official organizations, and national policies, but anthropologists—particularly cultural anthropologists—adopt ethnographic fieldwork as their primary research strategy (see Chapter 3). They live with a community of people over an extended period to better understand their lives by “walking in their shoes.”

The field’s cross-cultural and comparative approach considers the life experiences of people in every part of the world, comparing and contrasting cultural beliefs and practices to understand human similarities and differences on a global scale. The global scope of anthropological research provides a comparative basis for contemporary humans to see the seemingly unlimited diversity of and possibilities for cultural expression, whether in family structures, religious beliefs, sexuality, gender roles, racial categories, political systems, or economic activities.

Anthropologists have constantly worked to bring often-ignored voices into the global conversation. As a result, the field has a history of focusing on the cultures and struggles of non-Western and nonelite people. In recent years, some anthropologists have conducted research on elites—“studying up,” as some have called it—including financial institutions, aid and development agencies, medical laboratories, and doctors (Gusterson 1997; Ho 2009; Nader 1972; Tett 2010). But the vast majority of our work has addressed marginalized segments of society.

More information

A large group of pedestrians cross a crosswalk.

Anthropologists Study People and the Structures of Power. Human communities are full of people, the institutions they have created to manage life in organized groups, and the systems of meaning they have built to make sense of it all. Anthropology maintains a commitment to studying both the people and the larger structures of power around them. These include families, governments, economic systems, educational institutions, militaries, the media, and religions as well as ideas of race, ethnicity, gender, class, and sexuality.

To examine people’s lives comprehensively, anthropologists consider the structures that empower and constrain those people both locally and globally. At the same time, anthropologists seek to understand the “agency” of local people—in other words, the central role of individuals and groups in determining their own lives, even in the face of overwhelming structures of power.

Anthropologists Believe That All Humans Are Connected. Anthropologists believe that all humans share connections that are biological, cultural, economic, and ecological. Despite fanciful stories about the “discovery” of isolated, seemingly “lost” tribes of “stone age” people, anthropologists suggest that there are no truly isolated people in the world today and that there rarely, if ever, were any such people in the past. Clearly, some groups are less integrated than others into the global system currently under construction. But no group is completely isolated, and for some, their seeming isolation may be of recent historical origins. In fact, when we look more closely at the history of so-called primitive tribes in Africa and the Americas, we find that many were complex state societies before colonialism and the slave trade led to their collapse.

More information

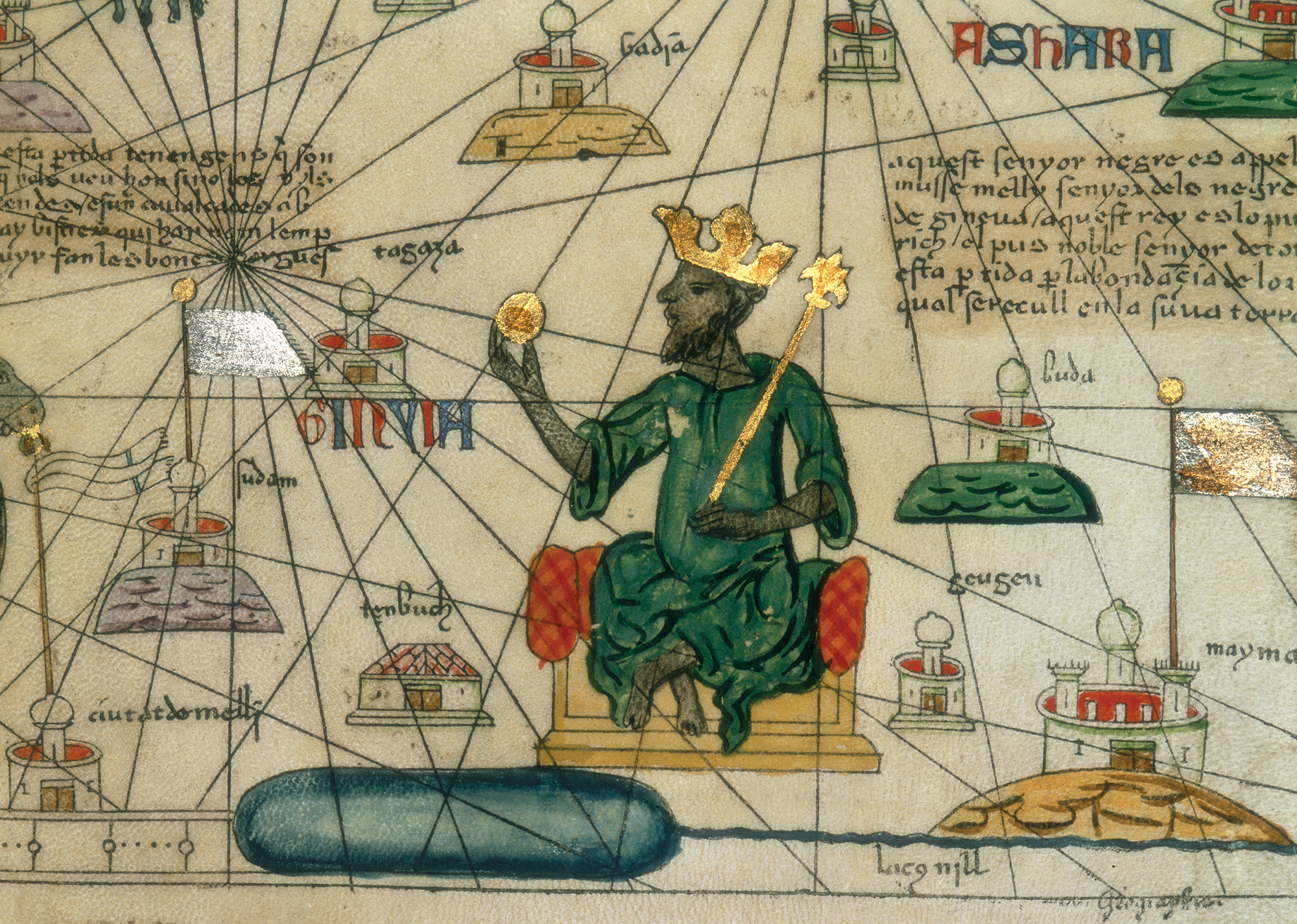

An illustration of Mansa Musa sitting on a throne. He is surrounded by depictions of key trade sites along with grid lines to indicate trade routes. Arabic text is written on the illustration.

Human history is the story of movement and interaction, not of isolation and disconnection. Yes, today’s period of rapid globalization is intensifying the interactions among people and the flows of goods, technology, money, and ideas within and across national boundaries, but interaction and connection are not new phenomena. They have been central to human history. Our increasing connection today reminds us that our actions have consequences for the whole world, not just for our own lives and those of our families and friends.

Glossary

- anthropology The study of the full scope of human diversity, past and present, and the application of that knowledge to help people of different backgrounds better understand one another.

- ethnocentrism The belief that one’s own culture or way of life is normal and natural; using one’s own culture to evaluate and judge the practices and ideals of others.

- ethnographic fieldwork A primary research strategy in cultural anthropology that typically involves living and interacting with a community of people over an extended period to better understand their lives.

- cross-cultural and comparative approach The approach by which anthropologists compare practices across cultures to explore human similarities, differences, and the potential for human cultural expression.