How Is Anthropology Changing Today?

Analyze how the author’s fieldwork exemplifies how globalization has changed anthropology.

The field of anthropology has changed significantly in the past forty years as the world has been transformed by globalization. Just as the local cultures and communities we study are changing in response to these forces, our focus and strategies must also change.

CHANGING COMMUNITIES

Globalization is changing the communities we study. Today, vulnerable people and cultures are encountering powerful economic forces that are reshaping family, gender roles, ethnicity, sexuality, love, health practices, and work patterns. Debates over the effects of globalization on local cultures and communities are intense. Critics of globalization warn of the dangers of homogenization and the loss of traditional local cultures as products marketed by global companies flood into local communities. (Many of these brands originate in Western countries, including Coca-Cola, Microsoft, McDonald’s, Levi’s, Disney, Walmart, CNN, and Hollywood.) Yet globalization’s proponents note the new exposure to diversity of people, ideas, and products that is now available to people worldwide, opening possibilities for personal choice that were previously unimaginable. As with the case of Filipino community pantry movement—and as we will see throughout this book—although global forces are increasingly affecting local communities, local communities are also actively working to reshape encounters with globalization to their own benefit: fighting detrimental changes, negotiating better terms of engagement, and embracing new opportunities.

CHANGING ENVIRONMENT

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of modern humans is our ability to adapt—to figure out how to survive and thrive in a world that is swiftly changing. Change has been a constant. So has human adaptation, both biological and cultural.

Our species has successfully adapted genetically to changes in the natural environment over millions of years. We walk upright on two legs. We have binocular vision and see in color. We have opposable thumbs for grasping. Our bodies also adapt temporarily to changes in the environment on a daily basis. We sweat to keep cool in the heat, tan to block out the sun’s ultraviolet rays, shiver to generate warmth in the cold, and breathe rapidly to take in more oxygen at high altitudes.

As our ancestors evolved and developed greater brain capacity, they invented cultural adaptations—tools, the controlled use of fire, and weapons—to navigate the natural environment. Today, our use of culture to adapt to the world around us is incredibly sophisticated. In the United States, we like our air conditioners on a hot July afternoon and our radiators in the winter. Oxygen masks deploy for us in sky-high airplanes, and sunscreen protects us against sunburn and skin cancer. Mask wearing, physical distancing, and vaccine production and distribution have been adaptations to the spread of COVID-19. These are just a few familiar examples of adaptations our culture has made. Looking more broadly, the worldwide diversity of human culture itself is a testimony to human flexibility and adaptability to particular environments.

More information

The decomposing body of a bird shows bottle caps, plastic, and other assorted trash in its stomach.

Shaping the Natural World. To say that humans adapt to the natural world is only part of the story. Humans actively shape the natural world as well. As we will explore further in Chapter 11, humans have planted, grazed, paved, excavated, and built on at least 40 percent of Earth’s surface. Our activities have caused profound changes in the atmosphere, soil, and oceans. Humans’ impact on the planet has been so extensive that scholars in many disciplines have come to refer to the current historical period as the Anthropocene—a distinct era in which human activity is reshaping the planet in permanent ways. Whereas our ancestors struggled to adapt to the uncertainties of heat, cold, solar radiation, disease, natural disasters, famines, and droughts, today we confront changes and social forces that we ourselves have set in motion. These include climate change, global warming, water scarcity, overpopulation, extreme poverty, biological weapons, and nuclear missiles. They pose the greatest risks to human survival. As globalization accelerates, it escalates the human impact on the planet.

Today, human activity already threatens the world’s ecological balance. We do not need to wait to see the effects. For example, Earth’s seemingly vast oceans are experiencing significant distress. In the middle of the Pacific Ocean sits a floating island of plastic the size of Texas, caught in an intersection of ocean currents. The plastic originates mainly from consumers in Asia and North America. Pollution from garbage, sewage, and agricultural fertilizer runoff, combined with overfishing, rising water temperatures and increasing acidity caused by carbon dioxide, has caused a 50 percent decline in marine populations over the past fifty years (World Wildlife Fund 2015). These sobering realities are characteristic of today’s global age and the impacts of increasing globalization.

Humans and Climate Change. Human activity is also producing accelerating climate change. Driven by the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, largely from the burning of fossil fuels, global warming is already reshaping the physical world and threatening to radically change much of modern human civilization (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2020). Changing weather patterns have already begun to alter agricultural patterns and crop yields. Global warming has spurred rapid melting of polar ice and glaciers, and the pace is increasing as sea levels begin to rise.

Anthropologists’ attention to climate change has taken on added urgency as the people and places we study are increasingly affected. Half of the world’s population lives within fifty miles of a coast, so the implications of sea-level rise are enormous—especially in low-lying delta regions. Bangladesh, home to more than 150 million people, will be largely underwater. Miami, parts of which already flood during heavy rainstorms, will have an ocean on both sides. Should all the glacier ice on Greenland melt, sea levels would rise an estimated twenty-three feet.

How will the planet cope with the growth of the human population from 8 billion in 2020 to more than 9.8 billion in 2050? Our ancestors have successfully adapted to the natural world around us for millions of years, but human activity and technological innovation now threaten to overwhelm the natural world beyond its ability to adapt to us.

CHANGING RESEARCH STRATEGIES

Anthropologists are also changing their research strategies to reflect the transformations affecting the communities we study (see Chapter 3). Today, it is impossible to study a local community without considering the global forces that affect it. Thus, anthropologists are engaging in more multisited ethnographies, conducting fieldwork in more than one place in order to reveal the linkages between communities created by migration, production, or communication. My own research is a case in point.

More information

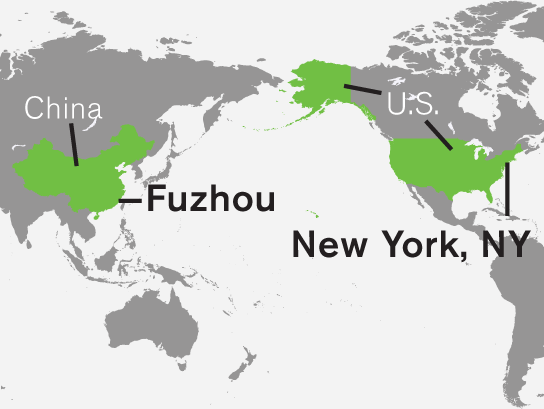

China and the United States are highlighted. Fuzhou is labeled within China. New York, New York is labeled within the United States.

Multisited Ethnography: China and New York. When I began my fieldwork in New York City’s Chinatown in 1997, I anticipated conducting a yearlong study of Chinese immigrant religious communities—Christian, Buddhist, and Daoist—and their role in the lives of new immigrants. I soon realized, however, that I did not understand why tens of thousands of immigrants from Fuzhou, China, were taking such great risks—some hiring human smugglers at enormous cost—to come and work in low-paying jobs in restaurants, garment shops, construction trades, and nail salons. To figure out why so many were leaving China, one summer I followed their immigrant journey back home.

More information

Crowds of people gather to worship with Buddhist monks in a temple.

I boarded a plane from New York to Hong Kong and on to Fuzhou, the capital of Fujian Province on China’s southeast coast. From Fuzhou, I took a local bus to a small town at the end of the line. A ferry carried me across a river to a three-wheeled motor taxi that transported me across dirt roads to the main square of a rural fishing village at the foot of a small mountain. I began to hike up the slope and finally caught a ride on a motorcycle to my destination.

Back in New York, I had met the master of a temple, an immigrant from Fuzhou who was raising money from other immigrant workers to rebuild their temple in China. He had invited me to visit their hometown and participate in a temple festival. Now, finally arriving at the temple after a transcontinental journey, I was greeted by hundreds of pilgrims from neighboring towns and villages. “What are you doing here?” one asked. When I told them that I was an anthropologist from the United States, that I had met some of their fellow villagers in New York, and that I had come to learn about their village, they began to laugh. “Go back to New York!” they said. “Most of our village is there already, not here in this little place.” Then we all laughed together, acknowledging the irony of my traveling to China when they wanted to go to New York—but also marveling at the remarkable connection built across the 10,000 miles between this little village and one of the most urban metropolises in the world.

Over the years I have made many trips back to the villages around Fuzhou. My research experiences have brought to life the ways in which globalization is transforming the world and the practice of anthropology. Today, 70 percent of the village population resides in the United States, but the villagers live out time-space compression as they continue to build strong ties between New York and China. They travel back and forth. They build temples, roads, and schools back home. They transfer money by wire. They call, text, Zoom, WeChat, and post videos online. They send children back to China to be raised by grandparents in the village. Parents in New York watch their children play in the village using webcams.

In Fuzhou, local factories built by global corporations produce toys for Disney and McDonald’s and Mardi Gras beads for the city of New Orleans. The local jobs provide employment alternatives, but they have not replaced migration out of China as the best option for improving local lives.

These changes are happening incredibly rapidly, transforming people’s lives and communities on opposite sides of the world. But globalization brings uneven benefits that break down along lines of ethnicity, gender, age, language, legal status, kinship, and class. These disparities give rise to issues that we will address in depth throughout this book. Such changes mean that I as an anthropologist have to adjust my own fieldwork to span the entire reality of the people I work with, a reality that now encompasses a village in China, the metropolis of New York City, and many people and places in between (Guest 2003, 2011). And as you will discover throughout this book, other anthropologists are likewise adapting their strategies to meet the challenges of globalization. Learning to think like an anthropologist will enable you to better navigate our increasingly interconnected world.